Surgical Treatment of Vascular Tumors of the Hand

Joshua Choo

Dean Louis

Morton Kasdan

DEFINITION

Vascular tumors are diverse and often have a confusing nomenclature. Part of the confusion resides in the ambiguity of the term tumor, which literally means “growth” or “swelling” but usually connotes a proliferative process. Vascular tumors were often named based on clinically descriptive terms (eg, strawberry hemangioma) rather than underlying histopathology. Consequently, the term vascular tumor has been applied to both nonproliferative and proliferative lesions.9 Similarly, the term hemangioma has been used to describe various vascular lesions that have different biologic behavior.14

Since 1996, the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) has adopted a standardized nomenclature to facilitate the classification, diagnosis, and treatment of vascular tumors.14

“Vascular anomalies” is now the widely accepted term for benign congenital vascular lesions that include both vascular tumors and vascular malformations.

The majority (90%) of vascular growths of the hand fall within this category (benign congenital lesions).

Vascular tumors, or hemangiomas, are true neoplasms characterized by endothelial proliferation. The most common vascular tumor is infantile hemangioma.

Vascular malformations are nonproliferative lesions that result from dysmorphogenesis. Examples of vascular malformations include capillary malformations, venous malformations, and congenital arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs). Many of these malformations have been historically mislabeled as hemangiomas (Table 1).

The remaining 10% of vascular lesions not included in the previously mentioned group include noncongenital vascular tumors, which may be benign (eg, glomus tumor) or malignant (eg, hemangioendothelioma, hemangiosarcomas, glomangiosarcoma, and malignant hemangiopericytoma), and traumatic or iatrogenic lesions, such as AVFs and pseudoaneurysms.

Table 1 Historical Terms for Vascular Anomalies

Vascular Anomalies

Tumors

Infantile hemangioma (strawberry hemangioma)

Lobular capillary hemangioma (pyogenic granuloma)

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma

Malformations

Arteriovenous malformation (arteriovenous hemangioma)

Venous malformation (cavernous hemangioma)

Capillary malformation (port-wine stain, capillary hemangioma)

Lymphatic malformation (lymphangioma)

Vascular anomalies are categorized into tumors and malformations. Note the historical terms in parentheses, which in many cases are misnomers.

The incidence of congenital vascular tumors and malformations in the general population is about 2% to 6%.20

Most are discovered at birth, although some may not be evident until adulthood.

About 15% to 26% of vascular anomalies present in the extremities,24,37 most commonly the hand and forearm.20

Vascular anomalies are fourth in frequency among upper extremity tumors, after ganglions, giant cell tumors, and inclusion cysts.

ANATOMY

Arteries in the hand terminate at either a capillary bed or a glomus body. The glomus is a specialized arteriovenous shunt that functions as a neuromyoarterial mechanoreceptor. It lies in the stratum reticularis of the skin, especially in the subungual region and distal pads of the digits. The glomus body acts as a thermoregulator and it regulates peripheral blood flow in the digits and possibly controls peripheral blood pressure. It contains the glomus cells surrounding the Sucquet-Hoyer canals, which are narrow vascular anastomotic channels.

PATHOGENESIS

Various theories for the pathogenesis of vascular tumors exist. Some implicate endothelial cells originating from disrupted placental tissue that becomes embedded in fetal soft tissue; others link hemangioma formation to abnormal circulating hematopoetic stem cells.27 Various theories exist as to the pathogenesis of vascular malformations, but broadly speaking, they are thought to occur as a failure of differentiation or involution of common embryonic vascular channels.24

Acquired vascular tumors are usually due to trauma that induces pseudoaneurysms or fistulas.

NATURAL HISTORY

Vascular Tumors

Infantile Hemangiomas

Also referred to as strawberry hemangiomas or capillary hemangiomas, infantile hemangiomas are the most common benign vascular tumor in infancy, with a reported incidence of 1% to 4% among Caucasian infants.37

Thirty percent of hemangiomas are visible at birth, but this increases to 70% to 90% before the infant is 4 weeks old.37

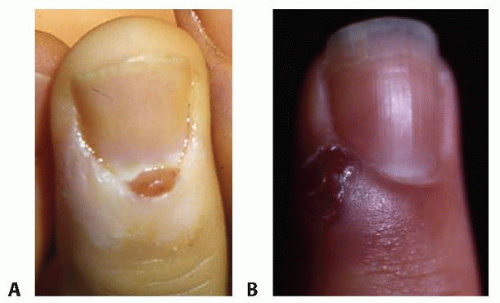

Hemangiomas typically are reddish lesions that become raised during the growth phase (FIG 1).

FIG 1 • Infantile hemangioma of the second web space of the right hand. Note the typical red color and raised appearance. During the proliferative phase, these lesions may ulcerate.

These lesions classically progress through a proliferative phase marked by rapid growth, an involution phase marked by gradual replacement with fibrofatty tissue, and resolution.34,36 As a general rule, the overall rate of involution among affected individuals occurs at 10% per year; thus, 50% of hemangiomas will involute by the time the child is 5 years old and 70% will involute by the age of 7 years.37 Exceptions do occur; a subset of infantile hemangiomas (rapidly involuting congenital hemangiomas or RICH) are characterized by a lack of a proliferative phase and complete resolution by 12 to 18 months of age, whereas another subset of hemangiomas (noninvoluting congenital hemangiomas or NICH) do not spontaneously involute.37 Because these hemangiomas also tend to be fully formed at birth, they are usually categorized separately as congenital hemangiomas to distinguish them from infantile hemangiomas.27

Histologically, hemangiomas are characterized by endothelial proliferation and consist of plump endothelial cells with high turnover rates.20 They may be further classified by other histologic features and location (superficial, subcutaneous, or intramuscular).24 Thirty percent of upper extremity hemangiomas will ulcerate, which becomes acute or chronic paronychia, especially in children who suck their fingers.33 Other complications include bleeding, infection, pain, and permanent skin changes after involution.37

If the hemangioma is associated with thrombocytopenia and consumptive coagulopathy, it is termed Kasabach-Merritt syndrome, which is unrelated to the size of the hemangioma and is associated with a 30% to 40% mortality.13 Multiple treatment modalities exist, including surgical extirpation, ablation, and/or compression, none of which are consistently efficacious.

Sclerosing hemangiomas contain a perivascular thickening of the lymphatic cells. These lesions have fibrous rather than a hematogenous origin and represent 10% of all hemangiomas.24

Although observation is the rule for infantile hemangiomas, occasionally, complications such as ulceration, slow regression, impairment of function, or psychosocial factors prompt intervention. Common agents include intralesional or oral corticosteroids and vincristine. Propranolol, a nonselective beta-adrenergic agonist, has in recent years been shown to be efficacious and safe in the treatment of hemangiomas. Although no clear protocols for its use in hemangiomas of the upper extremity exist, propranolol is a valuable therapeutic option that has changed the paradigm for hemangioma management and may be considered as an alternative to observation in problematic lesions.17

Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma

Kaposiform hemangioendotheliomas have been historically included with capillary hemangiomas.14 Although capillary hemangiomas, or infantile hemangiomas, have been reported to represent about 57% of subcutaneous hemangiomas, the incidence of true kaposiform hemangioendotheliomas is exceedingly small.19

Histologically, these lesions are distinguished from infantile hemangiomas by their characteristic tightly packed “can-nonball nests” of endothelial cells within the dermis, sheets of spindle cells, and close resemblance to Kaposi sarcoma.19

Clinically, these lesions do not spontaneously involute and the treatment modality with the most consistent results is vincristine alone or surgical resection.37

Lobular Capillary Hemangiomas

Lobular capillary hemangiomas, or pyogenic granulomas, make up 20% of the vascular tumors of the hand and may be a variant of a capillary hemangioma. They appear as a well-circumscribed lesion.

They develop rapidly and become pedunculated, friable outgrowths that are easily traumatized and bleed. In children, these lesions are more commonly found on the glabrous portion of the palm and digits as well as in the mouth and around the lips and face. In adults, they are more commonly found on the fingers and toes.

Vascular Leiomyomas

Vascular Malformations

Vascular malformations are uniformly present at birth but may not be visible until childhood, adolescence, or adulthood. Most appear by ages 2 to 5 years.36 They enlarge proportionately with the child unless they are stimulated by trauma, hormones, infection, or surgery.4 These lesions have an equal sex distribution. Malformations generally have flat, slowly dividing endothelial cells.

Vascular malformations present with a mass or skin discoloration depending on the depth of the lesion. They enlarge shortly after birth and grow with the child.31

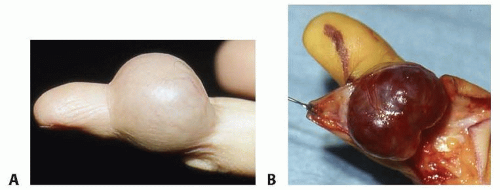

It is important to differentiate vascular malformations from hemangiomas because vascular malformations do not involute. Growth is due to progressive dilatation of the vessels and recurrence or regrowth after excision is due to alteration in hemodynamics and rerouting of flow through previously quiescent aberrant channels (FIG 4).

Patients with vascular malformations will complain of the mass effect of the lesion, increased size with exercise, or pain due to thrombosis. Elevation of the extremity eases symptoms. These lesions may lead to nerve compression at the forearm and wrist and digital compression may be seen with localized thrombosis.31,33

Vascular malformations consist of venous, capillary, arterial, and lymphatic malformations. Because up to 70% of vascular malformations are mixed, classification is not always straightforward. In the Hamburg classification, vascular malformations of the extremities are classified by the predominant vascular defect and by whether a truncular or extratruncular form, depending on involvement of a major axial vessel.3

Vascular malformations are also classified as either low-flow or high-flow lesions based on their radiographic appearance and clinical characteristics. Before the routine use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and Doppler ultrasound (US), angiography was used to estimate flow rates and shunt volume. Based on these findings, high-flow lesions were distinguished from low-flow lesions by the caliber and rate of opacification of feeding and draining vessels. The use of angiography has been augmented—and increasingly supplanted—by the development of Doppler US, nuclear scanning, and MRI, which have allowed more precise measurement of flow velocities, shunt volumes, and soft tissue anatomy.18

Low-flow malformations have large channels without intervening parenchyma and often are associated with phleboliths. These lesions are more common than high-flow lesions, representing 90% of vascular malformations. They consist mainly of venous, capillary, and lymphatic malformations.32

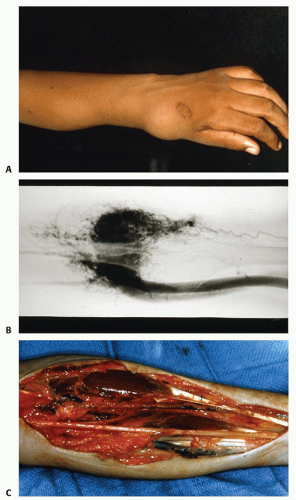

High-flow malformations usually have an arterial component and arteriovenous shunting. Marked enlargement and increased number of arteries, small vessels, and veins are consistent findings.5

High-flow malformations present early as a painless mass. They have a bimodal occurrence: 40% show up at birth and another 34% after 10 years old.31 They do not contract with elevation. Later in childhood, they can become painful and lead to distal ischemia or even high-output heart failure if large and untreated. They have been divided into three types:

Type A lesions have single or multiple AVFs, aneurysms, or ectasias involving the arterial side. They are localized to a specific anatomic region.32,36

Type B lesions consist of arteriovenous anomalies with microfistulas or macrofistulas that are localized to a single limb, hand, or digit. They have stable flow characteristics and provoke minimal to no distal symptoms. As with type A lesions, they remain localized to an anatomic region.32,36

Type C lesions enlarge slowly. They are diffuse, with microfistulas and macrofistulas involving all limb tissues. With increasing size, vascular steal occurs. They can cause distal ischemic pain, tachycardia, and congestive heart failure. Compartment syndrome, compression neuropathies, and ulceration secondary to ischemia or attempted surgical interventions can occur. The result can be unrelenting, progressive pain, eventually leading to amputation.31,32 These lesions are notoriously difficult to treat.32

Venous Malformations

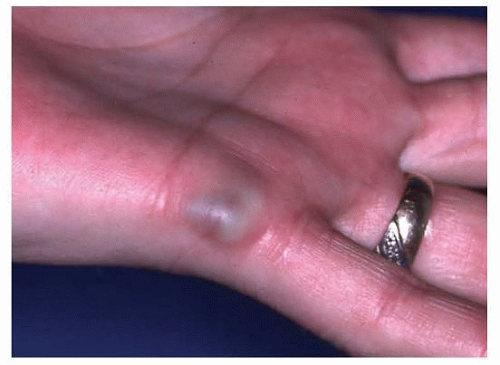

Historically termed cavernous hemangiomas (see Table 1), venous malformations represent the majority of vascular malformations and are also the most common vascular anomaly overall.31

Venous malformations are characterized histologically by thin-walled vessels and abnormally arranged smooth muscle cells that lead to ectatic changes over time, hence the term cavernous hemangioma.

Clinically, venous malformations present as bluish compressible nodules. Slow commensurate growth, compressibility,

and phleboliths are pathognomonic for venous malformations (FIG 5).20

FIG 5 • Venous malformation of the ulnar side of the left hand. Notice the blue color and slightly raised appearance.

They can occur in isolation or with any number of syndromes, including blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome or Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (see section on Syndromes Related to Vascular Malformations of the Hand and Upper Extremity).37

They may be associated with limb or digit overgrowth.31

Capillary Malformations

Capillary malformations, as known as port-wine stains or nevus flammeus, are a common congenital vascular malformation.37 They are dark red to purple and may have other associated vascular lesions. Over time, they become darker and acquire a cobblestone appearance.

Histologically, these lesions are characterized by a normal number of dilated capillaries and postcapillary venules in the upper dermis.

The treatment for these lesions is generally nonsurgical and consists of pulsed dye laser. Other modalities include intense pulsed light, photodynamic therapy, and angiogenesis inhibitors such as topical imiquimod and rapamycin.37

Arteriovenous Malformations

Arteriovenous malformations have direct arteriovenous shunts without intervening capillaries and, like venous malformations, may be associated with a number of syndromes, including Parkes-Weber syndrome and Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. These are more likely to be high flow and be complicated by ulceration and high-output failure as well as amputation (FIG 6).

As with venous malformations, arteriovenous malformations may be associated with limb or digit hypertrophy.31

Lymphatic and Mixed Malformations

Lymphatic malformations enlarge secondary to fluid accumulation, cellulitis, or inadequate drainage of lymphatic channels.20 They can limit hand motion, and infections are common.31 They can also cause bone hypertrophy (FIG 7).

Mixed vascular malformations share the characteristics of their combination of vascular malformations.

Syndromes Related to Vascular Malformations of the Hand and Upper Extremity

Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome is characterized by port-wine stains, combined low-flow vascular malformations (capillary, lymphatic, and venous), and limb enlargement due to hypertrophy of soft tissue and bone.37 Visceral malformations may occur as well.

Parkes-Weber syndrome, like Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, is also characterized by combined vascular malformations and skeletal hypertrophy of the affected limb. A distinguishing characteristic is the presence of high-flow lesions and complex multiple AVFs.18

Both of these syndromes may have significant medical sequelae, including congestive heart failure, pulmonary embolism, venous thrombosis, bleeding, and cellulitis.

Proteus syndrome is a progressive condition characterized by widespread cutaneous and subcutaneous nevi, lipoma, and mixed venous malformations.18

Maffucci syndrome is characterized by multiple endochondromas, exostoses, and venous malformations.18

Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome is characterized by multiple venous malformations of the skin. A distinguishing feature is the presence of gastrointestinal malformations that are at risk for bleeding.18

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree