Fig. 10.1

Compartment illustration. These cross sections at mid-calf level show the four compartments of the leg and their contents. Specifically, the superficial posterior (SP) and deep posterior (DP) compartments. The SP compartment contains the gastrocnemius, plantaris, soleus, and sural nerve. The DP contains the posterior tibial, flexor halluces longus, flexor digitorum longus musculotendinous units along with the tibial nerve, posterior tibial artery and vein

Radiography is rarely helpful in the diagnosis of muscular injuries but can rule out concomitant fractures, deformity, and complications such as myositis ossificans. Advanced imaging, however, can provide valuable information in the diagnosis of muscular injuries. Ultrasound can be used to confirm muscular strains or ruptures, but is operator dependent. Magnetic resonant imaging (MRI) can be a useful adjunct to the history and exam, especially if the diagnosis is in question or surgical intervention is being contemplated. MRI gives detailed anatomical information that can confirm the injury and help with preoperative planning. For example, the amount of retraction present in cases of muscle ruptures can be measured on MRI. Fascial defects can also be localized on MRI.

After a complete history and physical exam has been obtained and the muscular injury has been defined with or without the addition of advanced imaging, the examiner must go through a systematic process to determine optimal treatment. First and foremost, the examiner must stratify the patient’s risk of compartment syndrome. If acute compartment syndrome is identified, immediate surgical intervention is warranted. It is important to remember that although a patient’s exam can initially be benign, compartment syndrome can develop hours or days after an injury and patients should be appropriately counseled about this risk [1]. The specifics of compartment syndrome evaluation and treatment are detailed later in this chapter.

In the absence of acute compartment syndrome , most posterior leg muscle injuries can be treated conservatively. Occasionally, surgical intervention is indicated. This determination must be tailored on a patient-by-patient basis. Pertinent considerations include the type of injury, level of disability and loss of function from the injury, patient’s age and activity level, and any other medical comorbidity that could affect outcome.

Gastrocnemius Injury

Gastrocnemius injuries are the most common of all posterior leg injuries. A strain of the medial head of the gastrocnemius is referred to as “tennis leg.” In addition, the gastrocnemius is the most superficial therefore most likely to sustain a contact injury resulting in a muscle contusion . Contracture of the gastrocnemius is fairly common in the general population further putting this muscle at risk of strain or rupture.

Conservative treatment is the mainstay of gastrocnemius muscular injuries. Rarely, a complete rupture at the musculotendinous junction may require surgical repair . This would be diagnosed by marked weakness on plantar flexion with a bulge over the proximal muscle belly from retraction, similar to the commonly observed “Popeye” deformity resulting from proximal retraction of the biceps brachii muscle. Operative indications would include complete muscle rupture with inability to plantarflex through the ankle or a large partial tear resulting in intolerable weakness to the patient.

Surgical repair of a ruptured gastrocnemius can be approached in two patient positions: prone or lateral on a beanbag with operative side down. This is surgeon preference; however, each approach has its advantages. The prone position allows a direct posterior approach that can be extended to allow full visualization of the proximal and distal ends of the rupture. It also allows inline traction to be placed on the proximal end of the rupture to regain length if retraction did not allow direct tension free repair. Disadvantage of the posterior approach is a directly posterior positioned scar can be symptomatic to the patient. Also, the sural nerve can be injured during a posterior approach as it often crosses the operative field. The surgeon must identify and protect this neurovascular structure. Additionally, in very rare circumstances, the prone position can lead to blindness due to an increase in intra-orbital pressure. Although this risk is typically associated with extensive spine surgery, it is a devastating complication and should be a consideration during surgical planning. The lateral position with the operative side down allows a more minimally invasive technique to be used with a medial positioned incision. This type of incision allows the surgeon to more easily identify and protect the sural nerve reducing the risk of nerve injury. This positioning also avoids the risk of blindness. Another advantage of the lateral position is placement of a scar on the medial side of the calf is often more cosmetically appealing and less bothersome for the patient.

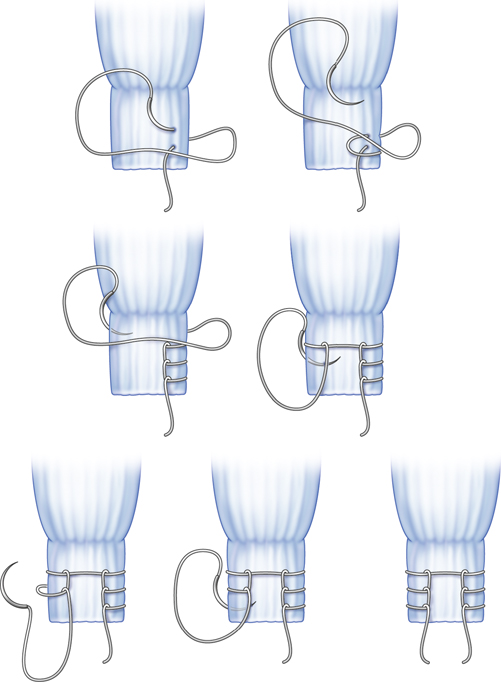

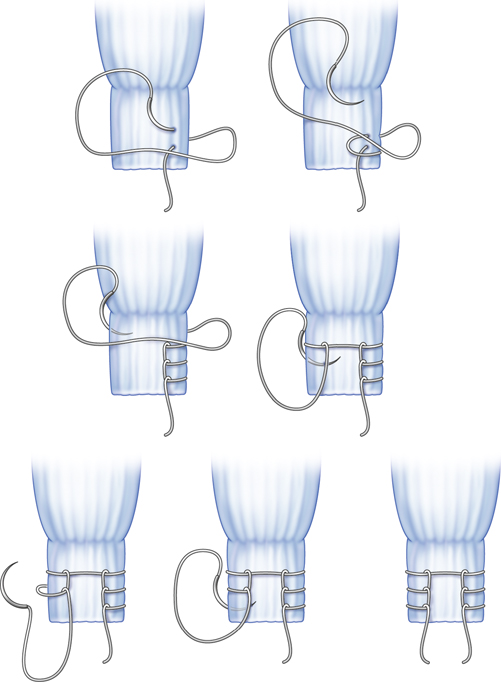

Regardless of the approach used, the elements of the surgery remain the same. First, a skin incision is made longitudinally of adequate length to have access to the proximal and distal ends of the rupture. Often, a 5–8 cm incision is suitable for this purpose. The dissection continues through the subcutaneous fat tissue being careful to coagulate any crossing venous bleeders to prevent postoperative hematoma formation. Next, the crural fascia is incised in line with the skin incision. This exposes the superficial posterior compartment. The most superficial structure is the gastrocnemius. In the setting of a recent injury, a hematoma will be noted upon entering the superficial posterior compartment. Once the tear is identified, the hematoma and any interposed fibrous tissue must be debrided, so that direct apposition of viable muscle can take place. Depending on the strength of the tissue, #2 or 2.0 fiberwire suture may be used to sew the ruptured ends to each other. A locking suture stitch technique (Krackow or Kessler stitch) will strengthen purchase in muscle tissue and help prevent pull through (Fig. 10.2). Additionally, the ankle may need to be placed into plantar flexion, relaxing the gastrocnemius, thus taking tension off of the repair. Knee flexion can also aid reducing tension on the repair as the gastrocnemius origin is on the femur. The patient should also be given muscle relaxation from the anesthesia team. The surgeon should be aware of the tension of the repair as well as the position of the ankle and knee at the time of the repair, which becomes important in postoperative splinting and rehabilitation protocol. After an adequate repair has apposed the ruptured ends of the muscle, the surgical wound closure should be done in layers. The crural fascia should be repaired with an absorbable vicryl suture (usually 3-0) to prevent any postoperative muscle herniation through the defect. The skin should then be apposed in a tension-free manner; an absorbable monocryl suture can be used for a cosmetic closure that does not require suture removal.

Fig. 10.2

Krackow stitch

After closure, a splint should be placed with the ankle in a position of tension-free plantar flexion as determined intraoperatively. The splint is usually only below the knee, however, it may be extended above the knee if needed for the repair to remain tension free. The splint remains in place for 2 weeks, and then it is removed for inspection of the incision and transition to partial weight bearing in a cam walker. Often, a heel lift is used to keep the ankle in equinus and reduce the tension on the repair. The height of the heel lift is determined by the surgeon, taking the amount of tension on the repair in mind. At 4–6 weeks post-op, gentle range of motion is begun under the guidance of a physical therapist. At 8–10 weeks, strengthening activities are advanced. Return to play is sports specific but usually occurs by 4–6 months.

Soleus Injury

Isolated soleus muscle ruptures appear to be uncommon and have been infrequently described in the literature . Indications for operative repair would be rare but include marked weakness on plantar flexion and disability after appropriate conservative treatment. Rest, ice, compression, and elevation along with cam boot or short leg walking cast immobilization for comfort are the treatments of choice until the pain and disability dissipate. If symptoms persist, physical therapy should be employed to focus on range of motion and strengthening. If over 6 months to 1 year of disability persist after appropriate treatment, surgical treatment may be considered. Similar techniques as described above for gastrocnemius ruptures are used. Pertinent differences do exist, however. The soleus muscle is the deep layer of the superficial posterior compartment of the leg. It lies underneath the gastrocnemius and originated on the posterior surface of the tibia, fibula, and interosseous membrane. It, therefore, does not cross the knee joint as the gastrocnemius does. It may be approached from a posterior or lateral approach. If approached posteriorly, the gastrocnemius tendon will need to be split to gain access to the soleus. Repair should be done in a similar fashion as described above for the gastrocnemius muscle. Patients’ postoperative course should also be followed as above.

Plantaris Injury

The plantaris is often considered a vestigial muscle. It lies in the superficial posterior compartment of the leg and may have a limited role in augmenting plantar flexion at the ankle. Given its limited function, minimal long-term disability occurs when it is ruptured. This fact makes the plantaris a good donor tendon to augment local surgical repairs (most often the Achilles tendon). Treatment of plantaris injuries is conservative and should follow a similar approach as outline for soleus muscle injury .

Tibialis Posterior Injury

The tibialis posterior is the dynamic support to hold the height of the medial longitudinal arch. Lengthening of this musculotendinous unit can lead to pes planovalgus deformity (acquired flatfoot). Muscular tears or ruptures are infrequent as the majority of injury occurs more distally along the tendon near its insertion on the navicular. There are no reports in the literature of posterior tibialis rupture at the muscle level. All reported cases are tendon ruptures more distally. However, if a complete rupture did occur and weakness on plantar flexion and inversion through the ankle resulted, operative repair should be considered. A repair would not only improve residual weakness but would also prevent an acquired flatfoot deformity from forming due to loss of dynamic support of the posterior tibialis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree