Surgical Treatment of Nerve Tumors in the Distal Upper Extremity

Christopher L. Forthman

Susanne Roberts

Philip E. Blazar

DEFINITION

Nerve tumors make up less than 5% of tumors about the hand and wrist.13

Most nerve tumors are benign and grow without causing neural dysfunction. As a result, the neural origin of a mass is often not anticipated and unexpected loss of function may occur after surgery.

The key is to prepare for excision of any mass by discussing the possibility of a nerve tumor with the patient, by recognizing patients and masses with a high likelihood of a nerve tumor, and by being familiar with surgical techniques that allow preservation or, if necessary, reconstruction of the affected nerve.

ANATOMY

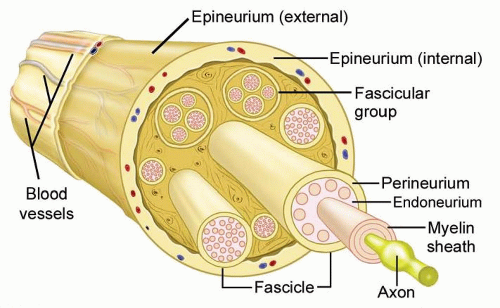

Peripheral nerves consist of axons surrounded by a nerve sheath (FIG 1).

The epineurium is a thin outer layer of connective tissue containing blood vessels that supply the nerve.

Perineural cells form a strong cellular layer, the perineurium, surrounding each fascicle (bundle) of axons.

An endoneurial layer of protective Schwann cells surrounds each individual axon.

PATHOGENESIS

Tumors of the peripheral nerve arise from and resemble components of the nerve sheath.

Most nerve tumors arise from the Schwann cell and are informally called schwannomas (or neurilemomas). Schwannomas surround the nerve.11

FIG 1 • Peripheral nerve anatomy. Individual axons travel together within a well-organized nerve sheath. The cells of the nerve sheath (not the axons) form the nerve tumor.

Neurofibromas also arise from nonmyelinating Schwann cells but are found within the substance of the nerve and cannot be enucleated from the fascicles.11

Other benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors (BPNSTs) include the granular cell tumor, neurothekeoma, nerve sheath myxoma, and perineurioma. Electron microscopy and immunohistochemistry may be necessary to determine the type of tumor and cell of origin in some cases.3

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs) arise de novo or from malignant change within a BPNST, usually a neurofibroma.

About half of MPNSTs occur in patients with neurofibromatosis (NF) type I (von Recklinghausen disease).

NATURAL HISTORY

Pediatric nerve tumors are uncommon.1

BPNSTs are typically painless and slow-growing, with malignant degeneration being exceedingly rare. Most tumors are relatively small (<2.5 cm), although they may cause nerve dysfunction due to focal impingement on the adjacent axons.

Patients with NF type I often have multiple schwannomas, neurofibromas, or both of major upper extremity nerves. Thick tortuous “plexiform” neurofibromas are common in NF type I and have a high risk of progression to malignancy.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The history should include the duration, growth characteristics, and local effects of the mass. Mild discomfort is common with nerve tumors, but pain is more consistent with MPNST than BPNST. Paresthesias are the exception rather than the rule. Hence, the possibility of a nerve tumor must often be entertained for the sake of completeness alone. Similarly, physical examination may suggest but cannot definitively diagnose a nerve tumor.

A complete examination of a distal upper extremity soft tissue mass should evaluate other nonneural possibilities within the differential diagnosis.

Ganglia: arise from joint and tendon sheaths in characteristic locations. The mass will typically transilluminate and the diagnosis can be confirmed by aspiration of highly viscous mucinoid material. Ganglia may mimic nerve tumors by causing compression of an adjacent nerve (eg, a ganglion in the canal of Guyon may cause ulnar neuropathy) (FIG 2).

Giant cell tumors (GCTs) of the tendon sheath: reactive lesions of synovium that occur about the palm and fingers in similar locations to nerve tumors. GCTs are often palpably nodular compared to the smooth margins of a nerve tumor.

Lipomas: These fatty tumors are usually more superficial and mobile than a nerve tumor. Rarely, lipomas grow in the carpal canal, causing median neuropathy.

Epidermal inclusion cysts: should be suspected when examination reveals evidence of prior penetrating trauma. Unlike neuromas, these cysts do not cause nerve symptoms and a Tinel sign is not present.

Nodular fasciitis: a firm, reactive soft tissue proliferation that may grow rapidly on the volar surface of the forearm or hand. The location may suggest a nerve tumor and the aggressive spread mimics sarcoma. Although most nerve tumors are mobile in the transverse plane, palpation of nodular fasciitis reveals dense adhesions to the adjacent subcutaneous tissue.

Patients with NF type I may have multiple nerve tumors, along with features such as café-au-lait spots, freckling in the axilla or groin, optic pathway tumors, iris hamartomas, and bone dysplasias. In patients with NF type 1, rapid growth of a neurofibroma, severe pain, and a new neurologic deficit often herald malignant degeneration.

Examination techniques include the following:

Palpation: The examiner moves the mass transversely and longitudinally. Nerve tumors may be translated transversely but are tethered in the longitudinal plane.

Sensory testing using Semmes-Weinstein monofilament. Early nerve compression increases threshold, whereas innervation density (two-point) remains normal. In a busy clinical practice, light moving touch may be as reliable (Stauch).12

The examiner assesses visible atrophy and weakness in motor units innervated by the affected nerve. Manual strength testing is usually normal.

Direct pressure is applied over the nerve just proximal to the mass. Nerves under compression by a mass are sometimes sensitive to touch and may produce paresthesias when manipulated.

The nerve is percussed immediately adjacent to the mass. A positive result is paresthesias in the cutaneous distribution of the nerve. The Tinel sign is positive only when an injured nerve is attempting to regenerate. Most nerve tumors do not have a positive Tinel sign.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographs should be obtained to look for intralesional calcification or invasion of adjacent bony architecture.

Intralesional calcification is rarely seen in BPNST and should alert the surgeon to the more likely possibility of a lipoma, hemangioma, GCT of tendon sheath, synovial chondromatosis, calcific tendonitis, myositis ossificans, or synovial sarcoma.

A malignant nerve tumor may invade nearby osseous structures.

Ultrasound is another good screening modality that can provide information about cystic or solid character, size, and an associated traceable nerve. Ultrasound cannot readily distinguish schwannomas, neurofibromas, and MPNST.

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the gold standard imaging modality and is useful for evaluating tumor characteristics, delineating the surrounding anatomy, and planning a surgical approach.

Localization of the tumor to the vicinity of a large nerve trunk suggests a peripheral nerve tumor (FIG 3A).

MRI may also occasionally demonstrate subtle muscle atrophy of the distally innervated musculature. Tumor margins are smooth and there is mild intralesional inhomogeneity.

Nerve tumors have intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images secondary to intermingled adipose tissue (FIG 3B).

BPNSTs are bright on T2-weighted images.14 These MRI features are similar to those of other soft tissue neoplasms and are not diagnostic.9

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree