24

Surgical Management of Patellofemoral Disease

This chapter offers the practicing orthopaedist a practical management approach to dealing with patellofemoral disease. The key to successful treatment relies on an accurate diagnosis of the underlying pathomechanics responsible for the pain resulting from patellofemoral pathology. Many factors have been implicated as a source of abnormal forces across the patellofemoral joint. These include patella alta; trochlear dysplasia; an abnormally increased quadriceps or Q angle, with secondary soft tissue problems; weakened or hypoplastic vastus medialis oblique quadriceps muscle with a contracted lateral retinaculum. These pathomechanics lead to abnormal forces across the patella, resulting in secondary degenerative changes or injury to the articular surfaces of the patellofemoral joint acutely or chronically.

Chronic patellofemoral pain is a common and problematic management issue. The term chondromalacia, which means soft cartilage, has often been applied to individuals suffering from anterior knee pain. Pain is a multifactorial perception. It is important to ensure that the pain is local and not referred. This is usually determined by a careful history and physical examination. The emotional well-being of the patient may modify the subjective response of pain. Even with obvious patellofemoral pathomechanics, if physical therapy has not been performed adequately to address these problems, then a repeated course of carefully directed physical therapy is worthwhile.

Physical therapy should address restoring soft tissue balance around the knee. This includes muscular and capsular balance; stretching to restore good flexibility of the quadriceps muscle, hamstrings muscle, and iliotibial band; as well as patellar mobilizations to loosen tight lateral capsular structures, proximal-distal quadriceps, and patellar tendon contractures. Patellar Mc-Connell taping to centralize a maltracking patella is worthwhile, and possibly patellar bracing to perform the same centralized tracking as well. A strengthening program that does not overload the damaged patellofemoral articulation utilizing isometric and short arc closed chain concentric and eccentric muscle strengthening is valuable.

When standard conservative measures have failed, surgical intervention followed by a careful rehabilitation is often successful if the underlying pathomechanics are addressed surgically. The sensitivity of imaging studies has greatly increased to assess anatomic variations, articular cartilage damage, and joint homeostasis by radionucleotide scanning. In addition to a careful physical examination to determine underlying pathomechanics, preoperative imaging is useful. I use a management algorithm, which is largely evidence based on the literature1 and new data from my use of autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) in the patellofemoral joint.2

Imaging Studies

Imaging Studies

Useful tests to assist in determining the diagnosis include standard radiographs to include standing anteroposterior (AP), 45 degree posteroanterior (PA) (Rosenberg views), lateral and skyline (Merchant views), and standard 54-inch axial alignment x-rays. Radiographs are useful with any patellofemoral joint to determine joint space narrowing or osteoarthritis on a standard Merchant view. This view is taken at 45 degrees of flexion during which the patella is normally well engaged in the trochlea distally. It is not an effective view for assessing maltracking. Maltracking, when it occurs, is usually in the first 20 to 30 degrees of flexion from extension. The dislocated or subluxed patella in full extension travels medially as the knee is flexed, capturing the trochlea as it reduces. This is the clinical finding of a reverse J sign.

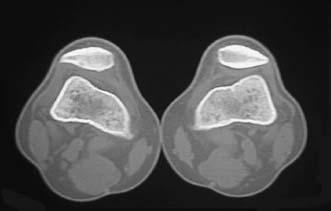

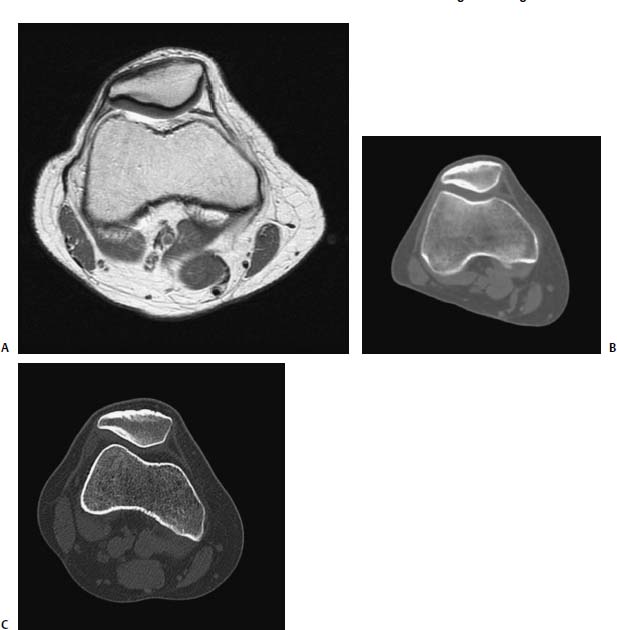

FIGURE 24–1 Bilateral subluxed patellae noted on computed tomography (CT) scan with quadriceps contracted.

A spiral computed tomography (CT) scan with the leg in extension performed with the quadriceps both relaxed and contracted assists in evaluating subluxation or dislocation of patella in the trochlea (Fig. 24–1) or dysplasia of the bony patellofemoral joint (Figs. 24–2 and 24–3). Accurate documentation of subluxation can be determined with a CT scan when clinical assessment is difficult, especially in the obese patient. When the pain pattern is suggestive of arising from the patellofemoral articulation, a bone scan is frequently useful to determine increased activity in that part of the joint.

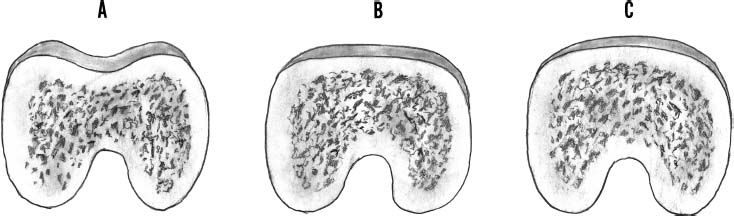

FIGURE 24–2 (A) Coronal view of a normal trochlea with a central concave groove. Variations of dysplasia may cause flattening of the groove (B) or a convex groove (C). When this occurs developmentally, the sesamoid patellar articulation is congruent to the dysplastic trochlea.

Assessment of articular cartilage injury is receiving more attention with newly developed imaging protocols enhanced by intravenous gadolinium as an indirect arthrogram. Although the gold standard for assessing articular injury remains arthroscopy, sensitivity and specificity >90% can be obtained with high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan using a standard 1.5-Tesla magnet, appropriate orthogonal gantry tilting to surfaces of the trochlea, and appropriate sequences. This is our preferred method of assessing articular cartilage injury to localize the site and size of chondrosis in the patellofemoral articulation. This work has been performed at our institution (Winalski) unpublished.

Pathomechanics Assessment and Treatment Selection

Pathomechanics Assessment and Treatment Selection

In a patient with persistent patellofemoral pain and functional disability, there are certain factors that need to be determined prior to appropriate treatment of the patient with patellofemoral disease. These factors are determined after the history, physical examination, x-rays, MRI scan, and CT scan when indicated. The factors include patellar tilt, patellar tilt and subluxation, location on the patella of articular chondrosis, location on the trochlea of articular chondrosis, the quadriceps angle, vastus medialis oblique (VMO) quadriceps hypoplasia or atrophy, patella alta, and dysplasia of the trochlea. Once these factors are accurately determined, then the treatment algorithm in Table 24-1 can be utilized.

Patellofemoral disease represents a spectrum with differing severities of subluxation, chondrosis, or arthrosis. This algorithm addresses the different stages of disease in a stepwise fashion of increasing severity dependent on the findings.

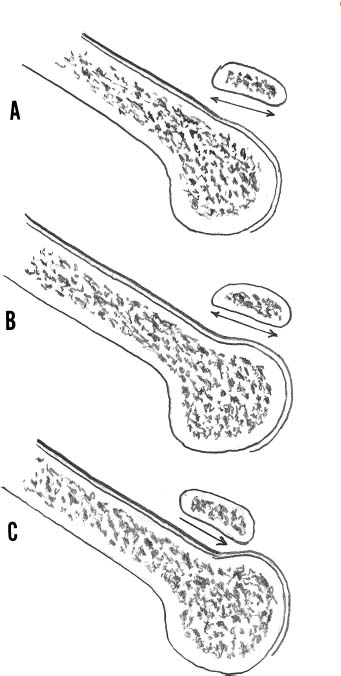

FIGURE 24–3 Dysplasia in the sagittal view may exhibit a smooth entry sulcus (A,B) or a prominence (C), which drives the inferior pole of the patella into a “speed bump.” If there is a commonly associated patella alta, it predisposes the patella to abnormal forces to subluxation and premature articular cartilage wear.

| Patellar Status | Cartilage Status | Treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patellar tilt only | Lateral release | |||

| Patellar tilt + subluxation | No chondrosis | Medial TTO | ||

| Tilt + sublux | Grade I, II chondrosis | AMZ, TTO (Fulkerson) | ||

| Tilt + sublux | Grade III, IV chondrosis | AMZ, TTO, ACI | ||

| Tilt + sublux | Loss of joint space | Patellofemoral arthoplasty and TTO |

ACI, autologous chondrocyte implantation; AMZ, anteromedialization; TTO, tibial tubercle osteotomy.

Patellar Tilt

The procedure of arthroscopic lateral release is an overly utilized procedure. It is effective for isolated patellar tilt without subluxation of the patella when the lateral retinacular structures of the patella are contracted and mobility of the patella is limited. There may be early grade 2 Outerbridge chondromalacia associated with a chronically contracted and nonsubluxated patella. The procedure should be performed either arthroscopically or open from the superior lateral pole of the patella to the inferior lateral aspect of the patellar tendon. The superior-lateral and inferior-lateral geniculate arteries are cut with this procedure and must be isolated, coagulated or tied. It is important not to release the tendinous portion of the vastus lateralis muscle from the superior lateral patella because of the ensuing weakness that will develop. Any loose partial-thickness chondrosis flaps should be removed at the time of the lateral release to limit any pain resulting from mechanical causes.

If subluxation is associated with patellar tilt, arthroscopic lateral release as an isolated procedure should not be performed. Persistent subluxation and mechanical overload, with subsequent progressive chondral wear and pain, will persist, resulting in a failure of the procedure and unnecessary surgery for the patient (Figs. 24–4 and 24–5). The importance of an accurate diagnosis in differentiating tilt and subluxation can be seen in a case presentation (Fig. 24–6), as an isolated lateral release would not have been effective. Instead, an isolated medialization of the tibial tubercle with lateral release is indicated.

Patellar Tilt with Subluxation and with or Without Chondrosis

When there is a combination of patellar subluxation and tilting, the usual causes include a lateralized tibial tubercle patellar tendon insertion and an abnormally increased Q angle, with accompanying soft tissue medial attenuation and lateral retinacular contracture. Chondrosis may have developed and dysplasia of the trochlea may be present.

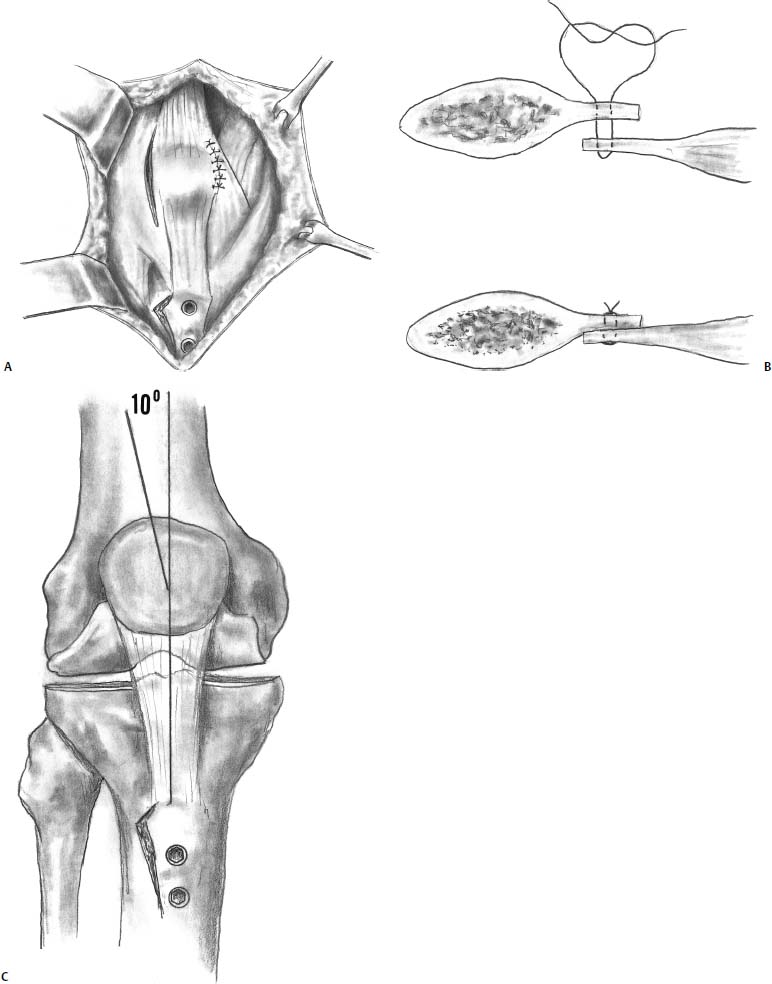

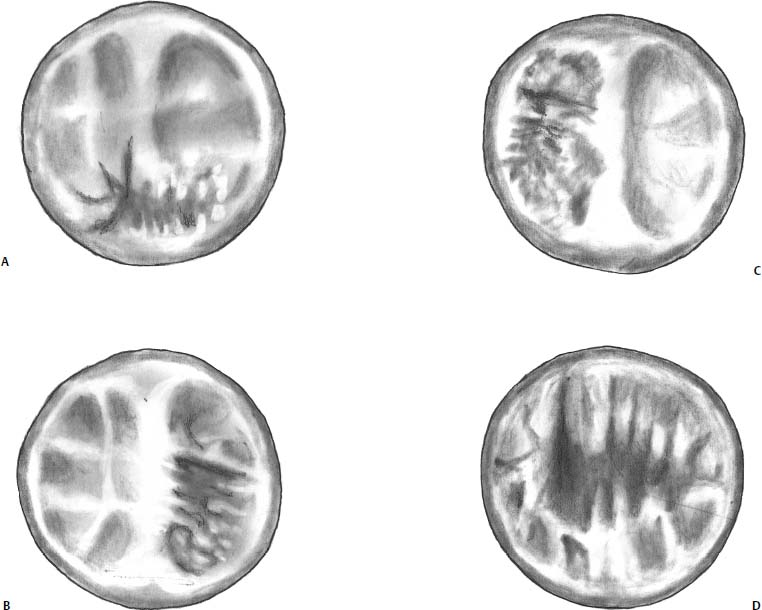

The surgical correction of the abnormal quadriceps vectors resulting from a lateralized tibial tubercle and lateral retinacular contracture need to be addressed. There have been various forms of tibial tubercle osteotomy (TTO) with lateral retinacular release performed over the years. The Fulkerson anteromedialization (AMZ) TTO has gained popularity in the United States (Fig. 24–7) as a modification of the Elmslie-Trillat procedure in that it allows a more aggressive anterior translation than that provided by the latter. Soft tissue balancing, which is required to centralize the patella in the trochlea, may also be concomitantly performed (Fig. 24–8). This procedure offloads the lateral and inferior poles of the patella by the anterior and medial translation of the tibial tubercle. Therefore, it loads off the proximal and medial poles of the patella. It has demonstrated successful clinical outcomes when the chondrosis involved with maltracking has been localized to the patella on the lateral facet or inferior patellar pole. Conversely, it has demonstrated poor clinical outcomes in the presence of articular damage to the proximal or medial patellar surfaces, or central trochlear involvement. This has led to the following classification of articular chondral injury to the patella locations: type 1, chondral injury to the inferior patella pole; type 2, chondral injury to the lateral patella facet; type 3, chondral injury to the medial patella facet; type 4, chondral injury to the proximal pole or panpatellar surface (Fig. 24–9).

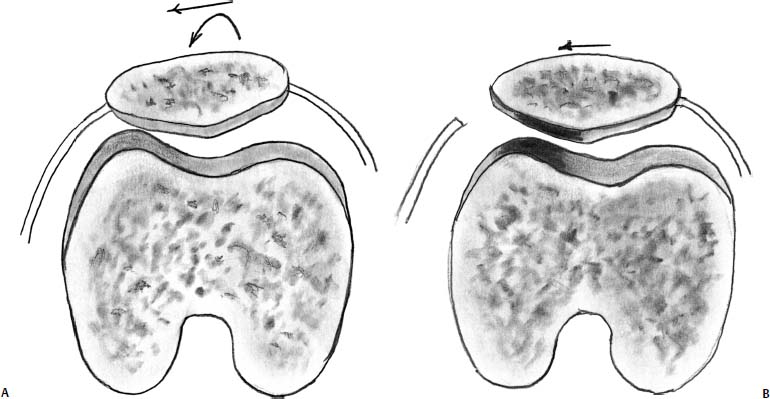

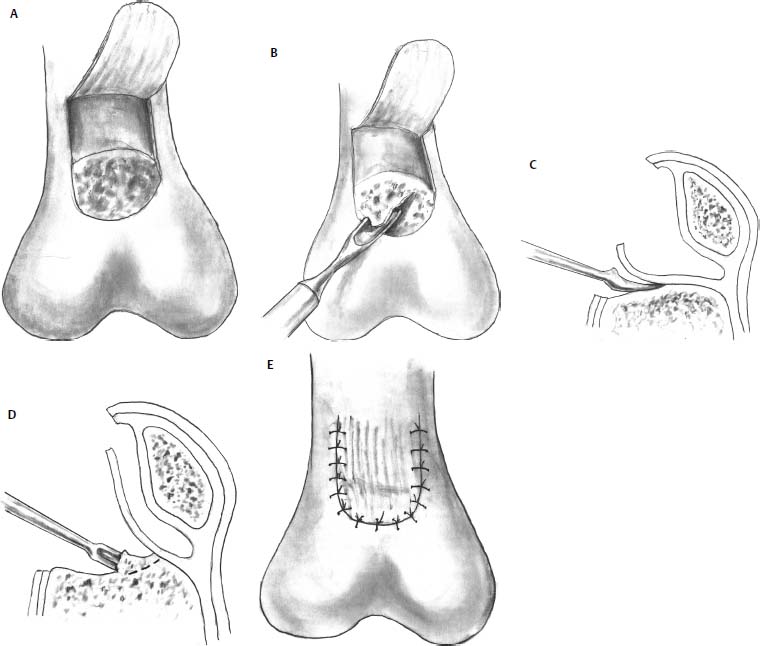

FIGURE 24–4 Isolated patellar tilt (A) is well managed by surgical release of the lateral retinaculum from the joint line to the superior lateral patellar tendon (B).

FIGURE 24–5 (A) When patellar tilt is accompanied by patellar subluxation, a lateral retinacular release does not correct the subluxation. (B) The overloaded lateral patellofemoral cartilage surfaces (open arrows) continue to experience overload with resultant progressive degeneration clinically manifested by persistent symptoms.

FIGURE 24–6 (A) A high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan with intravenous gadolinium utilized as an effective indirect arthrogram. Notice the full-thickness nature of the lateral patellar articular cartilage. This 32-year-old woman has had a history of “chondromalacia” since the age of 12 years. She has undergone multiple courses of physical therapy, taping, and bracing. She has been offered a patellar lateral arthroscopic release and has sought another opinion. (B) A CT scan of the patella, which is well reduced to position. Notice the thickening of the subchondral bone to the lateral patellar facet. This is indicative of chronic lateral maltracking and overload with remodeling of the subchondral bone. (C) The patient contracting her quadriceps with the leg in extension. Notice the lateral subluxation of the patella. The patient requires isolated medial translation of the tibial tubercle accompanied by a patellar lateral retinacular release. The articular cartilage was normal; therefore, there was no need for anterior translation of the tubercle.

Presently, we are reviewing the clinical outcomes of the first 45 patients who have been treated by ACI with full-thickness chondral lesions involving the patellofemoral joint.2 The follow-up has been 2 to 7 years. Our results when resurfacing type 3 and 4 chondral injuries to the patella have been successful with good clinical pain relief and improved function, whether or not there was preexisting patellofemoral maltracking requiring a Fulkerson osteotomy.

Trochlea Dysplasia

Dysplasia of the trochlea of the distal femur is an uncommon developmental abnormality leading to patellar instability and premature degeneration of the patellofemoral joint. It is occasionally associated with dysplasia of the lateral femoral condyle, leading to a valgus deformity accompanied by patellofemoral instability. The degree of dysplasia is variable, from subtle flattening of the proximal entry site to the trochlea, to a bulbous convex entry site leading to severe instability. As the patella is a sesamoid bone that develops secondary to its congruity with the trochlea, it is frequently flattened or concave on its large lateral facet to match the shape of the trochlea. Like developmental dysplasia of the hip, leading to premature osteoarthritis in the fifth decade of life, dysplasia of the trochlea also usually presents with instability, anterior knee pain, a diagnosis of chondromalacia, and end-stage isolated patellofemoral arthritis (more commonly in women in the fifth decade of life).

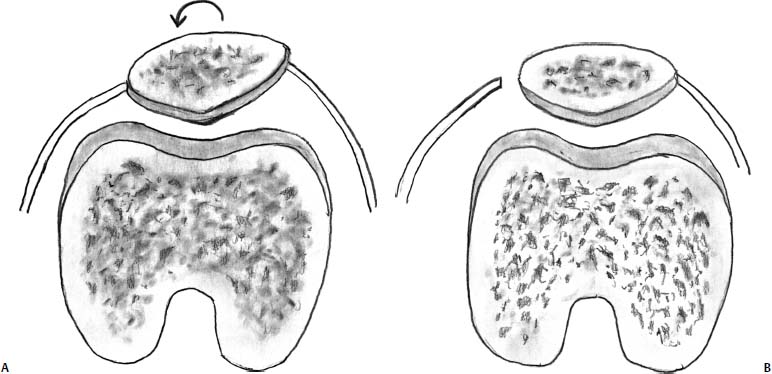

FIGURE 24–7 Diagrammatic illustration of an anterior medialization (Fulkerson) tibial tubercle osteotomy (AMZ TTO) (A) Anteroposterior view. (B) Axial view.

The diagnosis requires attention to the possibility of dysplasia of the trochlea. If a patient has recurrent instability, a lateral x-ray may frequently demonstrate a prominent proximal cylinder-shaped trochlea. The diagnosis is made most accurately by a CT scan with three-dimensional reconstruction and may also be seen on MRI scan (Fig. 24–10).

Patients frequently have undergone both open proximal soft tissue centralization of the patella and distal tubercle transfer with a failed clinical outcome and further instability episodes. The diagnosis is confirmed by clinical examination and demonstration of hypermobility in the medial to lateral direction, and a CT scan or MRI scan demonstrating a flattened or convex trochlea entry site. Surgical correction by interposition soft tissue synovial trochleoplasty may be performed with good success.3

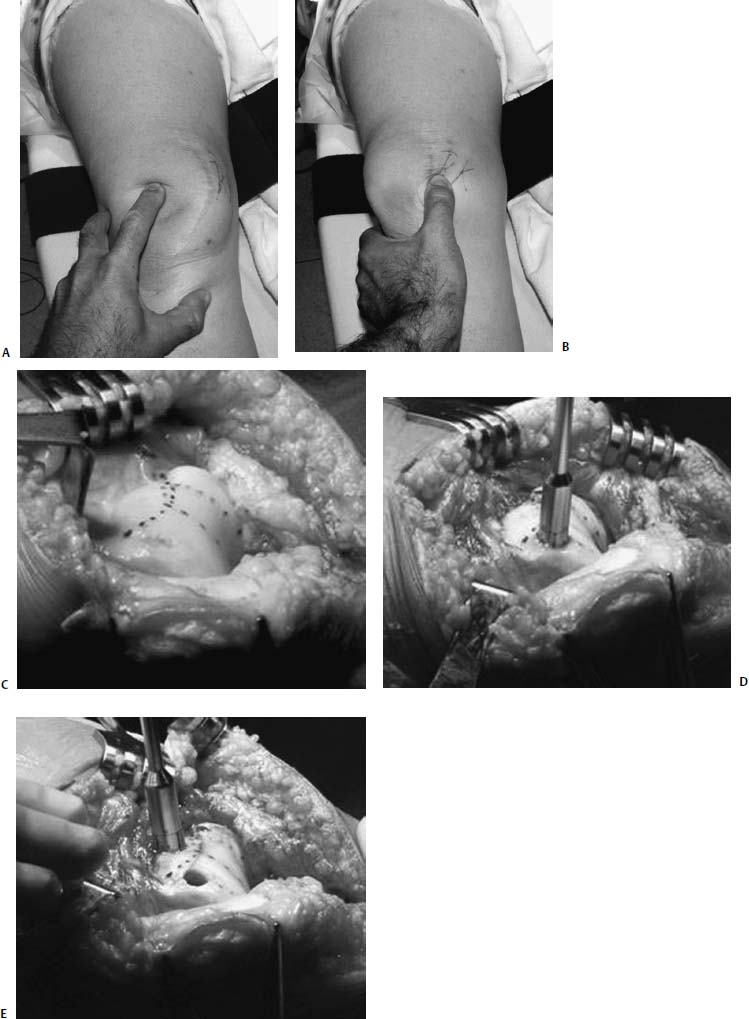

The procedure is outlined diagrammatically (Fig. 24–11), and an intraoperative case is described in Fig. 24–12.

For a successful surgical outcome, an accurate assessment of patellofemoral maltracking should always include an assessment of trochlea dysplasia.

Treatment

Treatment

Cartilage Repair with Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation

The Fulkerson osteotomy has demonstrated good and excellent clinical outcomes when the lateral patellofemoral maltracking is associated with chondral defects of type 1 or 2 locations (Fig. 24–9). However, if patellar tracking is central and there are chondral defects located on the medial facet, and there is a proximal patellar pole or panpatellar crush type of injury, then the results are poor.1

FIGURE 24–8 (A) Illustrations of an AMZ TTO combined with a lateral capsular release and a VMO advancement. (B) The VMO is placed “vest under pants” with a horizontal mattress stitch to both medialize the VMO and decompress the patella by further anterior translation with the soft tissue interposition. (C) Postoperative Q-angle is restored to 10 degrees.

FIGURE 24–9 The four categories of patellar chondrosis as defined by Fulkerson. (A) Type 1 involves the inferior patellar pole. (B) Type 2 involves the lateral patella facet. (C) Type 3 involves the medial patella facet. (D) Type 4 involves the entire patella or the proximal pole.

FIGURE 24–10 MRI scan demonstrating a patient with dysplastic trochlea. Note the flattened and convex nature of the proximal trochlea.

In this situation, the author has found that the use of cartilage repair with ACI has been extremely effective. The treatment is effective clinically and provides cartilage repair to the areas of loss. The standard factors previously mentioned in dealing with cartilage injury and degeneration with patellofemoral disease must be addressed prior to surgical repair of the articular cartilage injury, or at the same time as the ACI procedure.

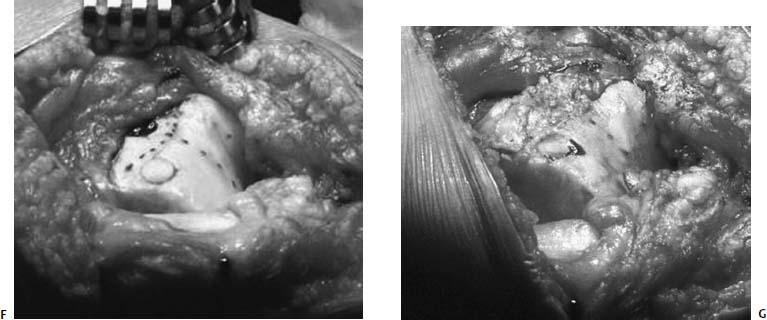

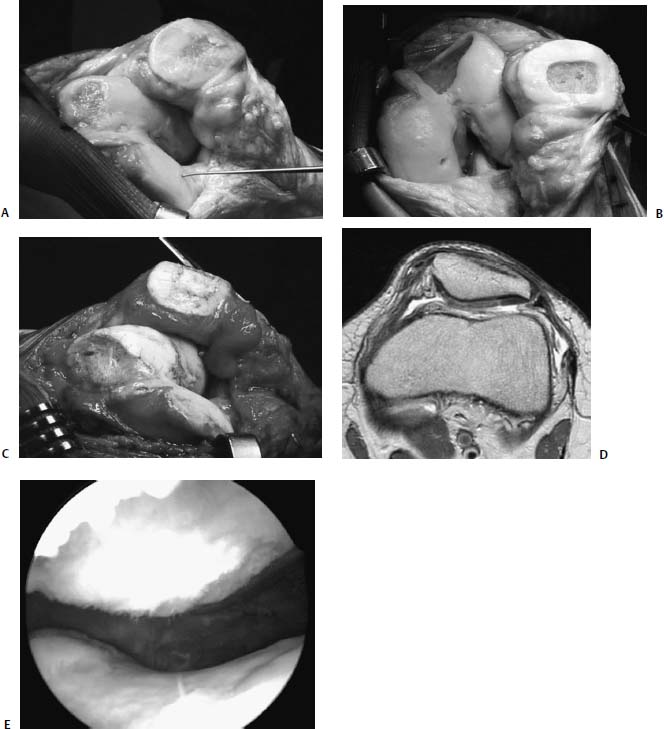

The surgical technique of ACI, and the specific aspects relating to the patellofemoral disease are beyond the scope of this chapter and are discussed elsewhere.4 Some of the technical considerations for ACI in the patellofemoral joint are illustrated in Fig. 24–13.

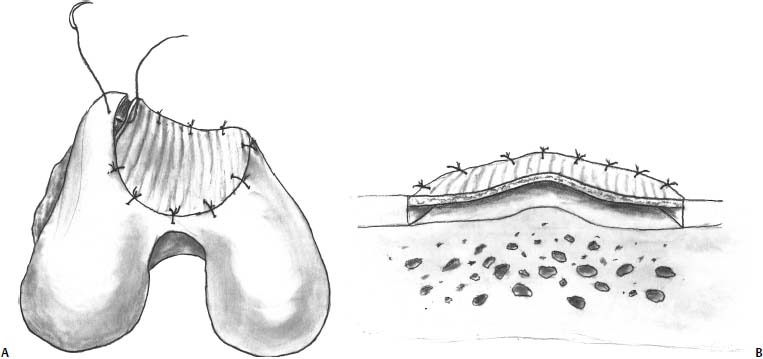

In my series of 45 patients (28 males and 17 females), the results of ACI in the patellofemoral joint have been encouraging. The average patient age was 37.5 years, with a range of 15 to 55 years. The average resurfacing per knee was 2.18 defects, with a surface area of 10.45 cm2 per knee. The patients had undergone an average of three surgeries prior to reconstruction with ACI. An example of a typical challenging ACI case of the patellofemoral joint, with a type 4 patella and trochlea defect pattern, is demonstrated in Fig. 24–14.

FIGURE 24–11 A diagrammatic illustration of a trochleoplasty. (A) The convex or flattened entry surface to the trochlea is identified centrally. The anterior supracondylar synovium is extraperiosteally reflected proximally. (B-D) The bulbous portion of the cartilage and bone is outlined with a sharp knife and removed with a sharp osteotome or curette. (E) The supracondylar synovium is then microsutured through the articular cartilage flush with the anterior femoral cortex acting as an interpositional soft tissue arthroplasty. After this procedure, the patella may capture and track centrally.

When assessing the first 45 patients treated with ACI for a patellofemoral joint, with a minimum 2-year follow-up, we have found patient satisfaction to be high. Overall 71% of the patients were satisfied, 16% were neutral, and 13% were dissatisfied. Compared with before surgery, 76% were better, 18% the same, and 6% were worse. Of patients who were asked if they would choose the surgery again, 87% said they would and 13% said they would not.

Overall, patients rated their results as follows: 71% good or excellent, 22% fair, and 7% poor. The average modified Cincinnati rating scale was 3.84 preoperative and 5.76 postoperative (p < .0001). Large clinical improvements and statistical significance were also encountered using the University of Western Ontario Macmaster Osteoarthritis Score (WOMAC) score, the Knee Society Score, and the Short Form (SF-36) score. These results are being prepared for peer review publication.

These results are similar to those found by Peterson et al5,6 when patellar maltracking was addressed at the time of surgery or corrected prior to the time of ACI. When their earliest cohort of patients was removed from the group with ACI that had not undergone patellar realignment surgery, their overall good and excellent results were 79%.5 These results have remained durable up to 10 years after implantation.6 These are excellent outcomes for a patient population that is difficult to treat.

FIGURE 24–12 (A,B) Prior open proximal soft tissue realignment and prior tibial tubercle osteotomy have not successfully stabilized this patient with recurrent lateral dislocations and medial subluxations. Her diagnosis of trochlea dysplasia has not been addressed. (C) Open appearance with central markings into the intercondylar notch demonstrating the central tracking path of the patella. The proximal markings represent the cartilage and bone to be removed, centering on the distal tracking pathway. (D) A recipient area of full-thickness cartilage loss is removed with an osteochondral harvester. (E) A donor osteochondral plug is being harvested from the proposed area of discarded cartilage and bone. The donor osteochondral plug measures 1 mm and is oversized to ensure a good press fit into the recipient site, measured to the same recipient depth. (F) The donor plug is transferred flush with the adjacent articular cartilage of the native trochlea; the proximal trochleoplasty can now be performed. (G) The final appearance of the joint after the synovium has been advanced to the area where the trochlcoplasty has been performed and where the donar plug was harvested from. The knee joint is closed with a medial advancement of the VMO. One year postoperatively the patient is asymptomatic with no recurrent instability of patella and an absence of anterior knee pain. The opposite knee similarly has failed open proximal and distal realignment procedures. It will also undergo open trochleoplasty to ensure stability. Bilateral disease is common in this condition.

FIGURE 24–13 (A) Diagrammatic representation of the proper suture technique required to restore the concave appearance of the trochlea when suturing the periosteum for autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI). The suturing technique should start centrally at the depth of the trochlear sulcus and alternate medially and laterally to restore the concave nature of the trochlea so as not to flatten out the shape. A flattened periosteal cover puts the graft at premature failure due to increased forces across the periosteal cover. (B) Diagrammatic representation of the proper suture technique required to restore the tent-like structure of the articular topography of the patella. The periosteal suturing must start at the apex of the patellar cartilage and then alternate medially and laterally until the periosteal cover is flush with the adjacent cartilage and the cartilage contour is restored. This prevents flattening of the periosteal cover and premature wear and failure of the ACI at the central bony apex.

FIGURE 24–14 (A) Appearance of the full-thickness loss of cartilage of the central patella and trochlea. A 32-year-old woman who had undergone a prior AMZ TTO 6 years earlier. She had good pain relief for approximately 4 years prior to recurrent crepitations, effusions, and severe anterior knee pain, limiting her performance of activities of daily living. Sports were not possible. (B) Appearance of the knee after radical debridement of all damaged articular cartilage back to full-thickness normal cartilage margins. (C) Appearance after marker suturing of periosteum and ACI. (D) MRI in the coronal plane across the patella 7 months postoperatively. This demonstrates excellent repair and tissue fill. The density of the tissue is not yet isodense to the adjacent native patellar cartilage. The patient had developed mild catching secondary to periosteal remnants on the patella. (E) Arthroscopic appearance of the patella and trochlea 8 months after ACI for “kissing” lesions—patella and trochlea. Two years postoperatively, the patient is pain free. She no longer experiences effusions, catching, or locking. She is able to participate in recreational sports and play with her young child.

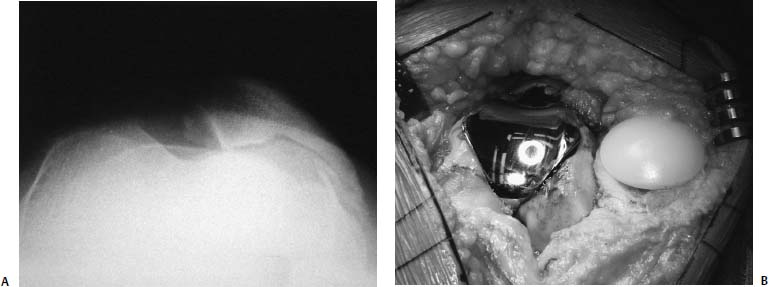

FIGURE 24–15 (A) Merchant x-ray view demonstrating obliteration of the articular joint space. (B) Intraoperative appearance of a patella femoral prosthetic resurfacing using a standard patella from an existing knee system with a custom designed inset trochlea metal surface.

Patellofemoral Prosthetic Arthroplasty

When collapse of the joint space radiographically has occurred, as viewed by the Merchant or skyline x-ray, cartilage repair by ACI is no longer possible. The procedure relies on intact, full-thickness cartilage margins to maintain the joint space so that the growing cartilage repair tissue may fill the defect. If the medial or proximal cartilage is absent, and there is no maltracking, then a tibial tubercle osteotomy with anterior and medial translation is also not effective. In this situation I have found that in the middle-aged patient who is too young for a total knee replacement, a unicompartmental patellofemoral prosthesis has been a useful interim solution. To date, a custom trochlea inset metal prosthesis with a standard polyethylene patella button has been used. The standard medial parapatellar arthrotomy is performed with a standard patellar resurfacing. The trochlea prosthesis is only 3 mm thick and removes little cartilage and bone. It is easily converted to a standard total knee replacement when the tibiofemoral cartilage becomes degenerated. It does not jeopardize future reconstructions, yet it allows adequate pain relief and functionality for activities of daily living (Fig. 24–15).

Conclusion

Conclusion

Patellofemoral disease is one of the most problematic management issues for the orthopaedist dealing with knee reconstructive surgery. Once nonoperative management has failed in alleviating pain and improving functionality, a careful assessment to determine the underlying pathomechanics causing the degenerative process is necessary for successful management. These factors include patella alta, an increased quadriceps angle, dysplasia of the trochlea, secondary soft tissue imbalance, and the localization of cartilage damage to the patella and the trochlea.

The management algorithm presented here attempts to deal with these identified factors and the secondary degenerative processes. When used for the correct indications, the options of patellar lateral release, anteromedial tibial tubercle osteotomy, trochleoplasty, ACI, and a unicompartmental patellofemoral prosthesis provide improved functionality and pain relief for the young patient suffering with patellofemoral pain.

REFERENCES

1. Pidoriano AJ, Weinstein RN, Buuck DA, Fulkerson JP. Correlation of patellar articular lesions with results from amteromedial tibial tubercle transfer. AJSM 1997;25:533–537

2. Minas T, Bryant T. The role of antologous chondrocyte implantation in the patellofemoral joint. Clin orthop 2005, 436: 30–39

3. Peterson L, Karlsson J, Brittberg M, et al. Patellar instability with recurrent dislocation due to patellofemoral dysplasia results after surgical treatment. Bull Hosp Jt Dis Orthop Inst 1988;48: 130–139

4. Minas T, Peterson L. Advanced techniques in autologous chondrocyte transplantation. Clin Sports Med 1999;18:13–44

5. Peterson L, Minas T, Brittberg M, et al. Two- to 9-year outcome after autologous chondrocyte transplantation of the knee. Clin Orthop 2000;374:212–234

6. Peterson L, Brittberg M, Kiviranta I, et al. Autologous chondrocyte transplantation. Biomechanics and long-term durability. Am J Sports Med 2002;30:2–12

< div class='tao-gold-member'>