Proximal femoral deformity is often associated with acetabular dysplasia. The correction of these deformities must consider the center of rotation of angulation as well as the joint orientation angle (medial proximal femoral angle) and the neck shaft angle. Femoral osteotomy can be performed on its own or in combination with greater trochanteric transfer. The location of the lesser trochanter must also be considered. Other considerations are the shape of the femoral head, the congruity of the joint, and the presence of acetabular dysplasia. Optimizing the anatomy of the hip joint offers the longest-term joint preservation and normalization of function.

- •

Proximal femoral deformity and hip dysplasia are interrelated: proximal femoral deformity can affect the final shape of the acetabulum.

- •

Although there has been a recent emphasis on femoral head shape and head/neck offset abnormalities, the neck shaft angle, medial proximal femoral angle, femoral neck length, and greater and lesser trochanter position are important factors when addressing hip dysplasia.

- •

Anatomic abnormalities of the proximal femur have an effect on abductor and hip flexor muscle function and strength.

- •

There are many surgical options to normalize proximal femoral anatomy that should be considered when treating hip dysplasia. Proper analysis of the abnormal geometry of the bony femur, as well as the abnormal lever arms around the hip related to the lesser and greater trochanteric positions, is an essential part of a successful surgical plan.

Introduction

Femoral deformity and acetabular dysplasia are often associated with each other. Femoral deformity can be secondary to primary hip dysplasia and hip dysplasia can be secondary to primary femoral deformity, because the forces of the femoral head on the acetabulum are integral to the development of acetabular depth and version and, conversely, the forces of the acetabulum on the femoral head are integral to the development of femoral neck inclination and version. The shape of the upper femur is also affected by any imbalance of muscle forces around it, such as from spasticity (cerebral palsy), paralysis (polio, Charcot Marie-Tooth) or even subtle neurologic disorders (eg, congenital pseudarthrosis with neurofibromatosis). This change in shape of the upper femur may lead to secondary dysplasia of the acetabulum ( Fig. 1 ). Coxa valga produces lateral and superior forces on the acetabulum, eventually leading to dysplasia. Anteversion of the femur similarly leads to less medial force on the acetabulum and creates an apparent coxa valga. Furthermore, the posterior location of the greater trochanter in the anteverted femur decreases the abductor muscle lever arm, decreasing the medial force on the acetabulum and promoting hip dysplasia. Acetabular dysplasia is often associated with femoral anteversion. Did the anteversion cause the dysplasia; did the dysplasia cause the anteversion; or are they both primary deformities associated with each other? The answer to this chicken-and-egg question remains unknown.

Coxa vara promotes increased medial forces on the hip and therefore better acetabular development. In soft bone diseases, coxa vara leads to coxa profunda and protrusio. Therefore, when coxa vara is seen with hip dysplasia, it is not the cause of the dysplasia. The likelihood is that both deformities developed as part of the original disease process. Examples of coxa vara with hip dysplasia are congenital coxa vara, congenital femoral deficiency, and Conradi-Hünermann syndrome.

Femoral deformities can also arise secondary to the treatment of hip dysplasia. For example, avascular necrosis of the proximal femur that occurs following nonoperative or operative treatment can produce a growth arrest of the upper femoral growth plate with either varus or valgus deformity of the femoral head on the femoral neck. Most of these cases do not manifest damage to the greater trochanteric apophysis and therefore there is significant overgrowth of the greater trochanter. Growth arrest also leads to coxa breva, which alters the abductor and psoas tendon lever arms. Avascular necrosis can also lead to deformity of the femoral head, resulting in coxa magna or elliptical or saddle-shaped femoral head.

Evaluation of Femoral Deformities Associated with Hip Dysplasia

The history and physical examination are important in the evaluation of deformities around the hip. This evaluation should include the hip range of motion, presence or absence of impingement, rotation profile of the femur and tibia, and hip flexion and abduction strength and pain.

Plain radiographs still provide most of the information needed. Abduction and adduction views are also helpful. Computerized tomography is especially useful to evaluate the shape of the femoral head and acetabulum. Magnetic resonance arthrography is useful to evaluate for labral abnormality and impingement.

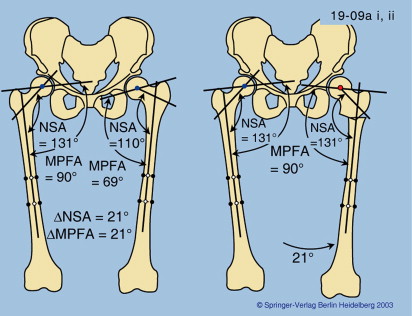

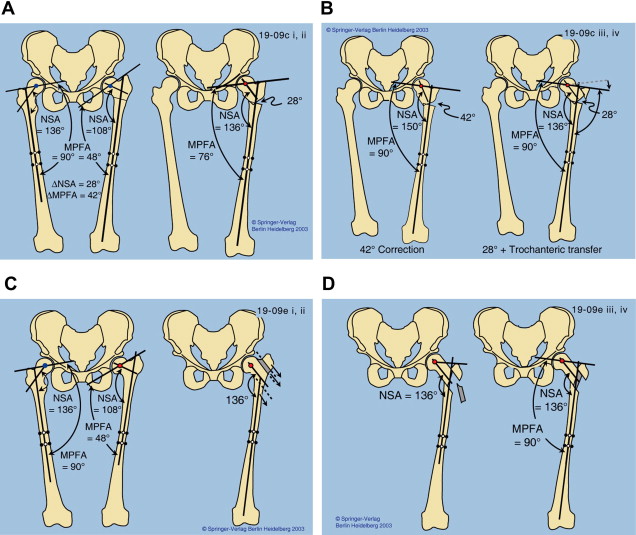

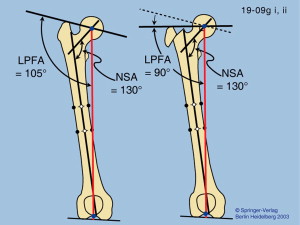

The joint orientation angles of the hip and knee in the frontal plane should be evaluated (medial proximal femoral angle [MPFA] and neck shaft angle [NSA] for both hips, and lateral distal femoral angle [LDFA] and medial proximal tibial angle [MPTA] for the knee). The difference between the MPFA of both hips should be compared with the difference between the NSA for both hips. If the differences are the same, then there is no trochanteric overgrowth. If the differences are different, then there is trochanteric overgrowth ( Figs. 2–4 ).

Indications for proximal femoral deformity surgery

There are 2 categories of surgery of the upper femur: intra-articular and extra-articular. Either or both may be indicated for joint preservation surgery of the hip. Indications for surgery are based on the history and physical, and the plain radiographic, computerized tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging studies. The presence of advanced arthrosis and stiffness may be a contraindication to joint preservation surgery. Even in asymptomatic patients there may be an indication for surgery because the prognosis for arthrosis and hip subluxation are known.

Indications for proximal femoral deformity surgery

There are 2 categories of surgery of the upper femur: intra-articular and extra-articular. Either or both may be indicated for joint preservation surgery of the hip. Indications for surgery are based on the history and physical, and the plain radiographic, computerized tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging studies. The presence of advanced arthrosis and stiffness may be a contraindication to joint preservation surgery. Even in asymptomatic patients there may be an indication for surgery because the prognosis for arthrosis and hip subluxation are known.

Types of proximal femoral deformities

Extra-articular proximal femoral deformities that involve the entire proximal femur include varus, valgus, flexion, extension, internal and external rotation, and shortening. Extra-articular femoral deformities that involve parts of the proximal femur are deformities of the greater and lesser trochanter relative to the rest of the proximal femur (eg, overgrowth of the greater trochanter, lesser trochanter too proximal and medial compared with normal). The location of the greater and lesser trochanter is important because both trochanters serve as the insertion point of 2 critical muscle groups. If the distance of these muscle insertions to the center of the femoral head is altered, lever arm dysfunction ensues manifested as muscle weakness and fatigue. When the greater trochanter is too proximal, then the muscle tension on the hip abductors is reduced. When the greater trochanter is too medial, as in cases of coxa breva, the abductor lever arm is reduced. The combination of reduced lever arm and reduced muscle tension leads to significant weakness that manifests as limp (lurch and Trendelenburg) and muscle fatigue during gait. If the lesser trochanter is too proximal and medial because of coxa breva, then the hip flexion may be weakened. Therefore, incorporating lateralization with distalization of the lesser trochanter is important to treat such weakness. It is important to test hip abduction and flexion strength before surgery.

Varus Osteotomy

The normal NSA of the femur is 130° ± 5°. Combined with a dysplastic acetabulum, valgus angles (>135°) predispose to subluxation. Although a pelvic osteotomy is the most important first step, combining it with a varus proximal femur osteotomy to stabilize the hip should be considered. The impact of the varus osteotomy is best exemplified by the Nishio varus osteotomy of the femur. This varus osteotomy of the base of the femoral neck was used on its own to treat hip dysplasia ( Fig. 5 ). Because the abductor lever arm is increased by this extreme varus osteotomy, the patient walks with minimal limp. This osteotomy challenges the belief that acetabular dysplasia must be treated by a pelvic, and not femoral, osteotomy, and supports Bombelli’s concept that coxa vara applies medial forces on the acetabulum that can change its shape over time.