, Antonio Cesarani2 and Guido Brugnoni3

(1)

“Don Carlo Gnocchi” Foundation, Milano, Italy

(2)

UOC Audiologia Dip. Scienze Cliniche e Comunità, Università degli Studi di Milano, Milano, Italy

(3)

Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Milano, Italy

Abstract

Unilateral vestibular hypofunction means asymmetrical vestibular functioning, i.e. the sensory input of one side is diminished with respect to that of the other side. A sudden unilateral loss or impairment of vestibular function causes vertigo, dizziness and impaired postural function. In the cases of vestibular nerve or labyrinth lesion, the key treatment is to cure the infection. Evidence suggests that vestibular neuritis is caused by reactivation of a latent Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection with the vestibular ganglia latently infected with HSV-1. In the case of vascular damage such as in vertebrobasilar insufficiency, the key treatment is restoring the arterial blood supply or venous brainstem drainage. In all the cases, the key impairment is acute vertigo in the first days and, immediately after, postural unsteadiness with instability of the visual field, especially when walking, turning or changing position. The rehab protocol showed into this chapter regards the rehabilitative treatment of patient during the stage of vestibular function sudden loss.

Unilateral vestibular hypofunction means asymmetrical vestibular functioning, i.e. the sensory input of one side is diminished with respect to that of the other side. A sudden unilateral loss or impairment of vestibular function causes vertigo, dizziness and impaired postural function.

Asymmetrical peripheral functioning can be also detected without the patient complaining of vertigo or instability. Such an asymmetry can be stable, being a sequela of a former lesion. It can be also fluctuant as, e.g. in cases with recurrent attacks of the Ménière’s disease. In a more restricted clinical context, unilateral vestibular hypofunction is considered as non-fluctuant unilateral loss, where compensation plays a fundamental role.

The most striking form is the syndrome with sudden loss in which the same signs and symptoms of a post-labyrinthectomy can be observed [1]. The course is characterized by four stages:

1.

Stage of irritation: In some cases, the onset of the syndrome may be characterized by a rather vague dizziness. At the moment the spontaneous nystagmus beats toward the affected side, and normal caloric reaction can be observed.

2.

Stage of sudden loss of function or paralysis of the system: Typical rotary vertigo is now experienced and spontaneous nystagmus beats toward the normal side. The caloric reaction is absent or reduced at the affected side. Patients are generally visited at the Emergency Room of the hospital during this stage, and hospitalization is common.

3.

Stage of central compensation: There is a progressive decrease of vertigo as well as of spontaneous nystagmus [2]. This occurs independently of the persistence of unilateral weakness or areflexia at the affected side which is revealed by caloric stimulations [3, 4]. Provocative manoeuvres (especially head shaking) reveal vertigo and nystagmus.

4.

Stage of recovery: When the function of the affected side recuperates, this may lead to a spontaneous nystagmus, reversed in direction, i.e. beating toward the affected side.

The most frequent causes of sudden unilateral vestibular loss are:

After benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo, vestibular neuritis is the second most common cause of peripheral vestibular vertigo. It accounts for 7 % of patients presenting to outpatient clinics that specialize in the treatment of dizziness and has an incidence of 3.5 per 100,000 population [7].

In the cases of vestibular nerve or labyrinth lesion, the key treatment is to cure the infection. Evidence suggests that vestibular neuritis is caused by reactivation of a latent Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection with the vestibular ganglia latently infected with HSV-1 [8–10].

In the case of vascular damage such as in vertebrobasilar insufficiency, the key treatment is restoring the arterial blood supply or venous brainstem drainage.

In all the cases, the key impairment is acute vertigo in the first days and, immediately after, postural unsteadiness with instability of the visual field, especially when walking, turning or changing position.

The following protocol regards the rehabilitative treatment of patient during the stage of vestibular function sudden loss:

5.1 Hospital Treatment

In the early phase of acute vertigo, symptoms are characterized by nausea and vomiting, rotary vertigo is present in every position of the head and the body with a slight decrease of symptoms lying on the opposite site of the lesion, oscillopsia due to nystagmus, unsteadiness with typically standing and gait deviations toward the affected side. The first mechanism of recovery is internuclear inhibition that can lead to a bilateral reduction of the vestibular responses. Successively, recovery is featured by sensory substitution phenomena.

The key aims of rehab are:

1.

Reduce antigravitary failure of the affected side

2.

Reduce oscillopsia due to nystagmus

3.

Activate sensory substitution phenomena

4.

Reduce internuclear inhibition

5.

Reactivate coordination

6.

Reduce spatial disorientation (vertigo)

In the acute phase, drugs are often necessary [11] especially those that reduce neurovegetative symptoms, such as metoclopramide, and those that can potentially activate neurochemical compensation pathways such as benzodiazepine and amantadine [12].

The first step of the rehabilitative treatment of acute vertigo is TENS (see Chap. 4 [13–15] (Fig. 5.1).

Fig. 5.1

The device used for vestibular electrical stimulation (Originally published in Alpini et al. [20] published by Springer © 1999)

One pair of electrodes must be placed on the paravertebral muscles opposite to the affected site (the side of the direction of the spontaneous nystagmus) and one pair in the trapezius muscle of the affected side.

Twice session/day, 45/50′ each have to be performed [16]. During the first 30′ patient remains in bed, possibly in the most comfortable position lying on the healthy side, in the light, trying to keep the eyes open and fixating a target on the opposite position of the visual field (on the side of the affected labyrinth).

Visual field may be stabilized reducing spontaneous nystagmus by means of pinhole glasses [17]. They are also known as stenopeic glasses (Fig 5.2), that is to say, eyeglasses with a series of pinhole-sized perforations filling an opaque sheet of plastic in place of each lens.

Fig. 5.2

Pinhole glasses, also known as stenopeic glasses: in place of each lens an opaque sheet of plastic with a series of pinhole-sized perforations

Similar to the workings of a pinhole camera, each perforation allows only a very narrow beam of light to enter the eye which reduces the size of the circle of confusion on the retina and increases depth of field. A second effect may appear at the common bridge between each two adjacent holes, whereby two different rays of light coming from the same object (but each passing through a different hole) are diffracted back toward the eye and onto different places on the retina. This leads to an increasing of patient’s fixation skill. They are not recommended for people with over 6 diopters of myopia.

For about 30′ patient is asked to remain sitting fixating a point through pinhole glasses, maintaining TENS cervical stimulation. Then the patient, under the effect of drugs, must reach the upright position and, accompanied by the therapist, have to begin walking.

Gait has to be performed during TENS, without wearing pinhole glasses, teaching to the patient fixating a target in front of him. After some steps the patient have to return back turning around her-/himself. The sense of rotation must not be casual but it must be in the sense of the health labyrinth. Instructions for re-fixating a target must be furnished.

After the first day of treatment, simple in-bed exercises must be performed, twice a day, for at least 20–30 min each session:

1.

The patient fixates a target on the ceiling and slowly moves her/his head rightward and leftward.

2.

The patient looks for two equidistant targets on the ceiling and then she/he fixates them alternatively first moving only the eyes and then moving only the head.

3.

The patient rotates her/his head in the direction of the affected labyrinth and fixates a target on the lateral wall. Then she/he takes her/his head straight maintaining the visual fixation. She/he counts until 10 and then she/he rotates again her/his head.

4.

5.

She/he repeats with the tip of the foot outward.

6.

She/he repeats with the tip of the foot inward.

7.

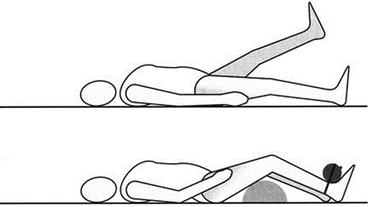

The patient puts a pillow under her/his leg on the affected side, bounding a 2 kg weight on her/his ankle with the flexed knee; then she/he extends it (Fig. 5.4).

Fig. 5.4

Extension of the right knee, binding a weight to the ankle, in a case of a lesion on the right (Originally published in Alpini et al. [20] published by Springer © 1999)

When it is possible to maintain sitting position, following exercises (one session a day, about 30′) have to be performed during cervical TENS stimulation:

1.

The patient extends her/his arms and lifts her/his thumbs. She/he takes her/his arms at about 50 cm, along a horizontal plane, from her/his eyes and then she/he fixates alternatively her/his thumbs. She/he begins slowly and then increases progressively the velocity of alternating the fixation.

2.

The patient extends her/his arms and lifts her/his thumbs. She/he takes her/his arms at about 50 cm, along a vertical plane, from her/his eyes and then she/he fixates alternatively her/his thumbs. She/he begins slowly and then increases progressively the velocity of alternating the fixation.

3.

The patient extends her/his right arm and lifts her/his thumb. She/he moves slowly her/his arm to and fro, along a horizontal direction, then along a vertical direction. She/he follows her/his thumb with eyes only, first slowly and then increasing progressively the velocity of thumb displacement.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree