Abstract

Objective

Oropharyngeal dysphagia is frequent in chronic neurological disorders and increases mortality, mainly due to pulmonary complications. Our aim was to show that submental sensitive transcutaneous electrical stimulation (SSTES) applied during swallowing at home can improve swallowing function in patients with chronic neurological disorders.

Methods

Thirteen patients were recruited for the study (4 f, 68 ± 12 years). They all suffered from neurogenic oropharyngeal dysphagia. We first compared the swallowing of paste and liquid with and without SSTES. Thereafter, the patients were asked to perform SSTES at home with each meal. Swallowing was evaluated before and after six weeks of SSTES using the SWAL-QoL questionnaire.

Results

With the stimulator switch turned on, swallowing coordination improved, with a decrease in swallow reaction time for the liquid ( P < 0.05) and paste boluses ( P < 0.01). Aspiration scores also decreased significantly with the electrical stimulations ( P < 0.05), with no change in stasis. At-home compliance was excellent and most patients tolerated the electrical stimulations with no discomfort. A comparison of the SWAL-QoL questionnaires after 6 weeks revealed an improvement in the burden ( P = 0.001), fatigue ( P < 0.05), and pharyngeal symptom ( P < 0.001) scales.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that SSTES is easy to use at home and improves oropharyngeal dysphagia quality of life.

Résumé

Objectif

La dysphagie oropharyngée est fréquente dans les pathologies neurologiques et augmentent la mortalité, du fait de complications respiratoires. Notre but était de montrer que la stimulation électrique sous-mentonnière trans-cutanée (SEST) réalisée à domicile pendant les repas pouvait améliorer la déglutition chez les patients souffrant d’une dysphagie oropharyngée d’origine neurologique.

Méthode

Treize patients ayant une dysphagie oropharyngée d’origine neurologique ont été inclus (4 f, 68 ± 12 ans). Ils souffraient tous d’une dysphagie oropharyngée d’origine neurologique. Dans un premier temps nous avons étudié les déglutitions de liquides puis de pâteux avec et sans la SEST. Dans un second temps, les patients on réalisés le traitement à domicile pendant les repas, la déglutition a été alors évaluée avant puis après six semaines de traitement par un questionnaire de qualité de vie spécifique à la déglutition (SWAL-QoL).

Résultats

Avec le stimulateur électrique en position « ON », la coordination de la déglutition était améliorée, avec une diminution du temps d’initiation du réflexe de déglutition pour les liquides ( p < 0,05) et les pâteux ( p < 0,01), avec une diminution des scores de fausses routes ( p < 0,05). À domicile, la compliance a été excellente, et la majorité des patients ont bien toléré le traitement. Après six semaines de traitement, il existait une amélioration de la pénibilité ( p = 0.001), de la fatigue ( p < 0,05) et des symptômes pharyngés ( p < 0,001).

Conclusion

Cette étude montre qu’il devrait être possible de mettre en place un traitement par stimulation électrique sous-mentonnière sensitive à domicile pour améliorer la dysphagie oropharyngée d’origine neurologique centrale.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Stroke and neurodegenerative disorders are the most common causes of oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults. Given the high prevalence and dramatic consequences of oropharyngeal dysphagia, including dehydration, malnutrition, aspiration, choking, pneumonia, and death, innovative neuro-rehabilitative treatments are required. Transcutaneous peripheral electrical nerve stimulation has been widely used in physiotherapy to treat chronic hemiplegia for over 10 years and seemed to improve motor function .

Electrical stimulation at the motor threshold has been used to treat oropharyngeal dysphagia in order to improve and enhance laryngeal elevation . It appears to be safe and effective in post-stroke dysphagic patients and as effective as physiotherapy . It is widely used in North America and appears to give better results when associated with swallowing, even if its efficacy and mechanisms of action remain to be determined .

A new conceptual approach for improving oropharyngeal dysphagia is to increase sensorimotor afferences to induce cortical plasticity of the swallowing cortex . In a previous study on transcranial magnetic stimulation of healthy subjects, we showed that the swallowing motor cortex is very plastic and changes after both voluntary swallowing and voluntary ventilation . Two approaches can be used to modify the swallowing motor cortex. The first is to use repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, which is known to modify the cortical representation . This technique has been shown to improve motor function in stroke patients . A number of studies have also reported that transcranial magnetic stimulation is effective in treating oropharyngeal dysphagia. We demonstrated, in a nonrandomized, open study, that it can restore swallowing coordination in post-stroke dysphagic patients . The second is to excite and modify the swallowing motor cortex using peripheral electrical stimulation . Pharyngeal electrical stimulation has been shown to improve swallowing function in post-stroke dysphagic patients . Given the difficulties inherent in using intra pharyngeal electrical stimulation in a home setting, we developed a technique that involves the electrical stimulation of submental muscles and showed that submental sensory transcutaneous electrical stimulation (SSTES) can improve swallowing coordination and decrease bronchial penetration in stroke patients . This study was performed in a hospital setting and involved the swallowing of thin waters.

The aim of our study, which was based on the concept of neuromodulation induced by peripheral electrical stimulation, was to show that SSTES could be used at home and could improve oropharyngeal dysphagia subsequent to chronic neurological diseases.

1.2

Methods

1.2.1

Patients

Thirteen patients (4 f, 68 ± 12 years) with stable chronic dysphagia and adapted feeding were recruited for the study. They understood the aim of the study and volunteered to participate in it. They did not suffer from other muscular disorders and had no contraindications to undergoing submental electrical stimulations. Motor function and overall neurological disability were assessed using Barthel index , which consists of a list of 10 items to evaluate functional dependence and provides a score ranging from 0 (total disability/dependence) to 100 (full function/independence). The procedures were approved by the local ethics committee.

1.2.2

Electrical stimulation

Electrical stimulations were performed using a commercial device for pain treatment that consisted of an electrical stimulator powered by a 9 V battery (TENS Neurostimulator, Schwa-medico GmbH, D 35630 Ehringshausen, Germany) and a pair of two self-adhering 3 cm 2 surface electrodes (Stimex, 68250 Rouffach, France) placed on the submental muscles.

1.2.3

Swallowing evaluations

Swallowing function was evaluated using a standardized videofluoroscopic barium swallow. Lateral and anteroposterior projection fluoroscopic images were acquired using a radio amplifier (Flexiview 8800, General Electric, United Medical Technologies Corp., Fort Myers, FL, USA) and recorded on a computer at 20 frames per second for later analysis (MMS, Tubingen, The Netherlands). The incisors anteriorly, the hard palate superiorly, the cervical spine posteriorly, and the proximal esophagus inferiorly were included in the field of the lateral projection. The patients were comfortably seated in a chair and were asked to not move during the video recording. They first swallowed three 5 ml boluses of high-density puree consistency barium suspension and, thereafter, three 5 ml boluses of high-density liquid consistency barium suspension. The procedure was stopped as soon as aspiration occurred. All boluses were delivered using a 20 ml syringe. Bolus transit measurements included oral transit time (OTT), which was defined as the interval between the first frame showing tongue tip elevation and the first frame showing the arrival of the head of the bolus at the ramus of the mandible; swallow response time (SRT), which was defined as the delay between the oral and pharyngeal phases of swallowing, that is, the interval between the OTT and the first frame showing upward excursion of the larynx; pharyngeal transit time (PTT), which was defined as the interval between the OTT to the last frame showing the tail of the bolus passing through the upper esophageal sphincter; and laryngeal closure duration (LCD), which was defined as the interval between the first frame showing contact between the inferior surface of the epiglottis and arytenoids and the first frame showing that contact had ceased.

Aspiration was scored using a validated eight-point penetration aspiration scale , while pharyngeal stasis was evaluated using a five cent coin and was scored using a five-point scale, where zero corresponded to no stasis and four to major stasis (> 20 mm) .

1.2.4

Swallowing Quality of Life questionnaire

Al the patients completed the SWAL-QoL. This French validated questionnaire is composed of 44 statements on deglutition-related aspects scored using a ten-point scale .

1.2.5

Protocol

A nurse presented the stimulator to the patient and the person assisting him or her during meals. They were shown how to position the stimulator, how to place the electrodes over the submental region lateral to midline, and how to switch the stimulator on and off. The stimulation intensity was established by determining the threshold sensibility using an incremental protocol. Three consecutive measurements were taken and the threshold was calculated as the mean of the three values. The stimulation intensity was then set at 120% of the mean threshold value. The stimulation frequency was set at 80 Hz. The duration was set at 30 min. An adapted consistency meal was then offered to the patient, and the accompanying person switched the stimulator on. If a mistake occurred when using the stimulator, the nurse corrected it.

Thereafter, submental electrical stimulations at the same intensity were performed and videofluoroscopic recordings were made. The stimulator was switched on or off at random. Three swallows of pudding and three swallows of liquid were studied when the stimulator was switched on and when the stimulator was switched off. The investigators were blinded to whether the videofluoroscopy studies were pre- or post-stimulation.

The patient was then sent home with the stimulator and the intensity was noted. The electrical stimulations were performed at the sensory threshold during a maximum 30 minutes at every meal for six weeks. After six weeks, the patient returned to the hospital for a consultation. The patient completed the SWAL-QoL questionnaire at the beginning and at the end of the six-week period. The observance was clinically notified.

1.2.6

Data and statistical analyses

The swallowing times for the liquid and paste boluses were compared when the stimulator was switched on and switched off. The various scales of the questionnaire were compared before and after the six weeks of electrical stimulations. The results are expressed as means ± standard errors (SE). Differences were calculated using a Wilcoxon paired test. Differences were considered significant when the probability ( P ) of a type I error was 0.05 or less.

1.3

Results

The characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1 . Six patients had post-stroke dysphagia, one had multiple sclerosis, one had Parkinson’s disease, and five had progressive supranuclear palsy. Of the six stroke patients, five had a hemispheric stroke and one had had a brainstem stroke. They all had a severe handicap as evaluated by the Barthel index. None were on non-oral feeding and all had moderate oropharyngeal dysphagia.

| Patients | Age | Sex | Barthel index | Pathology | SSTES | Dysphagia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n o 1 | 69 | m | 70 | Brainstem stroke (pons and cerebellum) | + | 36 months |

| n o 2 | 79 | m | 50 | Hemispheric stroke (fronto parietal, left) | + | 48 months |

| n o 3 | 81 | m | 70 | Hemispheric stroke (lacuna) | + | 36 months |

| n o 4 | 70 | m | 55 | Hemispheric stroke (fronto parietal, left) | + | 48 months |

| n o 5 | 77 | f | 70 | Hemispheric stroke (frontal, right) | + | 50 months |

| n o 6 | 72 | m | 75 | Hemispheric stroke (frontal, right) | + | 36 months |

| n o 7 | 56 | f | 20 | Multiple sclerosis | – | 24 months |

| n o 8 | 84 | m | 30 | Parkinson | + | 24 months |

| n o 9 | 70 | m | 60 | Progressive supranuclear palsy | + | 6 months |

| n o 10 | 67 | m | 40 | Progressive supranuclear palsy | + | 11 months |

| n o 11 | 70 | m | 30 | Progressive supranuclear palsy | + | 10 months |

| n o 12 | 59 | f | 15 | Progressive supranuclear palsy | + | 8 months |

| #13 | 70 | f | 20 | Progressive supranuclear palsy | + | 6 months |

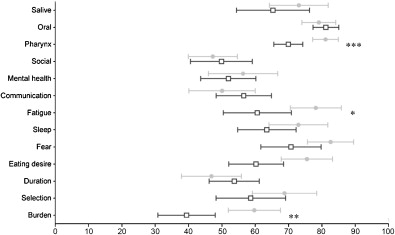

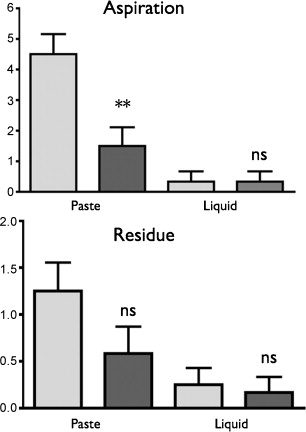

All the patients had poor quality of life in terms of oropharyngeal dysphagia, especially burden, food selection, communication, and social life ( Fig. 1 ). The videofluoroscopy assessments showed that all the patients had a neurogenic dysphagia profile with alterations in the oral stage, an increase in pharyngeal transit time, and a delay in swallow response time ( Table 2 ). The delay in the swallow response caused laryngeal aspiration and/or bronchial penetration of liquids ( Fig. 2 ).

| Without SSTES | With SSTES | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paste | OTT | 1.13 ± 0.35 | 1.07 ± 0.17 | 0.49 |

| SRT | 1.80 ± 0.28 | 1.32 ± 0.25 | 0.01 | |

| PTT | 2.34 ± 0.27 | 2.13 ± 0.26 | 0.45 | |

| LCD | 1.18 ± 0.09 | 1.31 ± 0.51 | 0.30 | |

| Liquid | OTT | 0.73 ± 0.12 | 0.49 ± 0.05 | 0.45 |

| SRT | 0.82 ± 0.25 | 0.48 ± 0.13 | 0.003 | |

| PTT | 1.40 ± 0.25 | 1.20 ± 0.17 | 0.09 | |

| LCD | 1.18 ± 0.10 | 1.10 ± 0.09 | 0.15 | |

All the patients and the accompanying persons quickly understood how to use the stimulator and position the electrodes (< 30 min). During the videofluroscopy, when the stimulator was switched on, swallowing coordination improved for all the patients, with a decrease in SRT for the liquid ( P < 0.05) and paste boluses ( P < 0.01). OTT, PTT, and LCD did not change significantly ( Table 2 ). The aspiration scores also decreased significantly with the electrical stimulations ( P < 0.05) while stasis did not change ( Fig. 2 ).

One patient refused the SSTES (n o 7). The twelve patients who accepted returned home with the stimulator. They placed the electrodes on the submental muscle and switched on the stimulator during meals. Compliance was excellent and all patients said that they used it at every meal during the six-week period. Most patients tolerated the electrical stimulations with no discomfort. One presented a skin allergy, which required a change in the type of electrode. The SWAL-QoL questionnaire revealed there was an improvement in the burden scale ( P = 0.001), an improvement in the fatigue scale, except for two patients ( P < 0.05), and an improvement in the pharyngeal symptom scale ( P < 0.001) for all patients after six weeks ( Fig. 1 ).

1.4

Discussion

We showed that the quality of life associated with neurogenic chronic oropharyngeal dysphagia can be improved with SSTES during swallowing when used at home for six weeks. SSTES improved swallowing coordination. However, our study gave rise to a number of questions.

We only enrolled volunteers with mild dysphagia who suffered from liquid aspiration due to a delay in swallow reaction time, a classic cause of neurogenic dysphagia . The aim of our study was to determine whether SSTES was a feasible home treatment option that could increase the ‘well being’ of these severely handicapped patients. Terre et al. reported that temporal swallowing function can be improved within 3 to 6 months in stroke patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia . While non-specific effects may have caused the improvement, this study included patients with a very long post-stroke delay and patients with a neurodegenerative disease that resulted in dysphagia lasting for 6 to 24 months. As such, even though a placebo or non-specific effect cannot be excluded, it is unlikely, event if there was no control group. The QoL questionnaire was specifically designed for patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia (SWAL-QoL) by Colleen McHorney and validated in french by our research group . This tool has proven useful for measuring the functional impact of swallowing disorders and assessing the effects of different interventions and treatments. The original SWAL-QoL scale has 44 items that score different aspects of a patient’s quality of life. The items are grouped into 10 lifestyle scales: burden of eating difficulty, eating duration, eating desire, food selection, communication, fear, mental health, social impact, fatigue, and sleep. It also includes a symptom-frequency scale in which each item is scored from 1 to 5 (1 for poorest QoL, 5 for best). A separate score (relative to 100%) was calculated for each scale, with each item having the same importance. There is no global QoL score. We showed that submental electrical stimulation resulted in a decrease in the burden of eating, fatigue due to eating difficulty, and pharyngeal symptoms based on the videofluoroscopy results.

Oropharyngeal dysphagia is associated with high morbidity and mortality, and is a drain on health systems. Dysphagia rehabilitation is thus a desirable goal and can be defined as the initiation of therapy to maximize the degree of recovery following a swallowing insult. Transcutaneous electrical stimulation studies of dysphagia rehabilitation have been carried out with the goal of improving muscle strength . More recently, we showed that submental electrical stimulations under the motor threshold performed for 1 h every day for 5 days, (electrical trains: 5 s every minute, 80 Hz) during swallowing improves swallowing coordination . Sensory neuromodulation is an elegant way to explain the success of electrical stimulations. Pharyngeal electrical stimulation applied 10 min once a day for 3 days compared to sham stimulation improved dysphagia, with a decrease in time to discharge from hospital of acute stroke dysphagic patients .

One hypothesis of the mechanism of action of electrical stimulation in improving swallowing disorders could be a reorganization of the swallowing motor cortex. The responses to 10 min of unilateral faucial pillar stimulations compared to sham stimulations in healthy volunteers showed that twitch-like stimulations of the tonsillar pillars may influence the neural pathways involved in swallowing initiation . However, the effect can be either beneficial or detrimental, depending on the stimulation frequencies used. Moreover, functional magnetic resonance imaging has shown that electrical stimulations applied directly to the pharyngeal mucosa induce pharyngeal cortical reorganization. This suggests that neuromodulation of the pharynx may stimulate cortical motor reorganization. The results of Doeltgen et al., who showed that electrical stimulation of the submental muscles (SSTES) of 25 healthy volunteers at 80 Hz increases cortico-bulbar activity and can induce plastic changes in the primary motor cortex, corroborate this effect . Submental electrical stimulation may thus modify the swallowing motor cortex. This suggests that the positive effect we report in the present paper may be caused by a modification of the sensory cortex or of cortical excitability. Nevertheless, a direct brainstem effect cannot be ruled out since it has already been shown that some brainstem plasticity exists .

The frequency specificity of the induced effects is a major concern . The time course over which these effects evolve suggests that a mechanism similar to long-term potentiation is involved and that they result from a coincident excitation of presynaptic and postsynaptic cells. If this is the case, the effects induced by submental electrical stimulation would be similar to those reported in the context of paired associated stimulations where coincident activation of cortical neurons by afferent inputs (peripheral nerve stimulation) and transcranial magnetic stimulation induces cortical excitability . Similarly, during submental electrical stimulation, afferent sensory inputs produced by the electrical stimulation are paired with endogenous excitation by the swallowing command. The frequency of electrical stimulation is crucial because low frequency (10 Hz) stimulation had an inhibitory effect while high frequency (80 Hz) stimulation had a facilitatory effect . Based on the paired association, it can be posited that submental electrical stimulation should be used only during swallowing. However, the duration of the treatment during swallowing is not defined. We arbitrary used six weeks, but the precise duration should be ascertained. It should also be determined whether adjunctive therapy like swallowing reeducation by a speech therapist could optimize the rehabilitation.

In the present study, which involved a small sample population, we showed that submental electrical stimulations can be used at home with excellent compliance. The stimulator was very easy for patients and their entourage to use and improved oropharyngeal dysphagia symptoms. A cohort study involving a large population of patients using sham and real stimulations will be required to determine whether submental electrical stimulation can ameliorate malnutrition and pulmonary infections, the two main complications of dysphagia.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

Les accidents vasculaires cérébraux et les troubles neurovégétatifs sont les premières causes de dysphagie oropharyngée chez l’adulte. Au vu de la forte prévalence de la dysphagie oropharyngée et ses conséquences dramatiques : déshydratation, malnutrition, fausse route, étouffement, pneumonie…, il est nécessaire de trouver de nouvelles pistes de rééducation.

La stimulation électrique trans-cutanée des nerfs périphériques est largement utilisée en rééducation fonctionnelle de l’hémiplégie chronique depuis plus de dix ans et semble améliorer les fonctions motrices . La stimulation électrique au seuil moteur permet le traitement de la dysphagie oropharyngée en améliorant et augmentant l’élévation du larynx . Ce traitement semble être sans danger et efficace chez les patients dysphagiques après un accident vasculaire cérébral avec la même efficacité que la kinésithérapie . Il est couramment utilisé en Amérique du Nord et les résultats sont même améliorés quand on associe cette stimulation électrique trans-cutanée à la déglutition, même si son efficacité et ses mécanismes d’actions restent à définir .

Un nouvelle approche visant à améliorer la dysphagia oropharyngée propose de stimuler les afférences sensitives afin d’induire une plasticité corticale de l’aire motrice pharyngée . Dans une étude précédente sur la stimulation magnétique trans-crânienne (TMS) chez des sujets sains, nous avons montré que le cortex moteur pharyngé est doté d’une grande plasticité et se modifie après des déglutitions volontaires et lors de ventilation volontaire . Deux approches peuvent être utilisées pour influencer ce cortex moteur pharyngé. La première consiste à utiliser de manière répétitive la TMS pour modifier la représentation corticale . Cette technique a fait ses preuves dans l’amélioration des fonctions motrices chez les patients après un accident vasculaire cérébral (AVC) . Plusieurs études montrent que la TMS est efficace dans le traitement de la dysphagie oropharyngée. Nous avons rapporté dans une précédente étude ouverte non-randomisée, que cette technique était capable de rétablir une coordination de la déglutition chez les patients dysphagiques post AVC . La seconde approche consiste à stimuler et modifier le cortex moteur pharyngée à l’aide d’une stimulation électrique périphérique . La stimulation électrique pharyngée a prouvé son efficacité dans l’amélioration fonctionnelle de la déglutition chez le patient dysphagique après un AVC . Du fait des difficultés liées à l’utilisation à domicile de la stimulation électrique intra-pharyngée nous avons mis au point une technique de stimulation électrique des muscles sous-mentonniers et nous avons démontré que la stimulation électrique sous-mentonnière trans-cutanée (SSTES) améliore la coordination de la déglutition et réduit les risques d’inhalation chez les patients après un AVC . Cette étude a été conduite dans un milieu hospitalier et consistait à avaler de l’eau gélifiée. Le but de la présente étude, basée sur le concept de neuromodulation induite par la stimulation électrique périphérique, était de démontrer que la SSTES pouvait être utilisé à domicile pour améliorer la dysphagie oropharyngée secondaire à des maladies neurologiques chroniques.

2.2

Méthodes

2.2.1

Patients

Treize patients (quatre femmes, âge moyen 68 ± 12 ans) ayant eu un AVC compliqué de dysphagie oropharyngée stable avec une alimentation adapté ont été inclus dans l’étude. Ces patients ne présentaient pas d’autres troubles neurologiques ou musculaires et n’avaient aucune contre-indication à la SSTES. L’indice de Barthel nous a permis d’évaluer le niveau moteur et le déficit neurologique de ces patients, cet indice consiste en une liste de dix items évaluant la dépendance fonctionnelle et fournit un score allant de 0 (dépendance complète) à 100 (autonomie complète).

2.2.2

Stimulation électrique

Les stimulations électriques ont été réalisées à l’aide d’un appareil commercialisé pour le traitement de la douleur, comprenant un stimulateur électrique alimenté par une pile de 9 V (TENS Neurostimulateur, Schwa-medico GmbH, D 35630 Ehringshausen, Germany) et une paire de deux électrodes de surface autoadhésives mesurant 3 cm 2 (Stimex, 68250 Rouffach, France) placées sur les muscles sous-mentonniers.

2.2.3

Evaluations de la déglutition

Nous avons étudié la déglutition par vidéofluoroscopie avec une acquisition des images par amplificateur de brillance (Flexiview 8800, General Electric, United Medical Technologies Corp., Fort Myers, FL, USA) et un enregistrement sur ordinateur à 20 images par seconde (MMS, Tubingen, The Netherlands). Les incisives antérieures, la partie haute du palais, la colonne cervicale supérieure et la partie inférieure de l’œsophage proximal ont été inclus dans le champ de projection. Les patients étaient confortablement assis sur une chaise avec instruction de ne pas bouger pendant l’enregistrement des images. Ils devaient tout d’abord avaler trois bolus baryté pâteux de 5 ml suivis de trois bolus baryté liquides de 5 ml. La procédure était immédiatement stoppée en cas d’inhalation. Tous les bolus étaient délivrés à l’aide d’une seringue de 20 ml. Les mesures du transit comprenaient : le temps de transit oral (TTO), défini comme l’intervalle entre la première image montrant l’élévation du bout de la langue et la première image montrant l’arrivée de la tête du bolus au ramus de la mandibule ; le temps de réaction à la déglutition (TRD), est défini comme le délai entre les phases orale et pharyngée de la déglutition, c’est à dire entre le TTO et l’élévation du larynx ; le temps de transit pharyngé (TTP), l’intervalle entre le TTO et la dernière image montrant la fin du bolus passant à travers le sphincter œsophagien supérieur ; et enfin le temps de fermeture laryngée (TFL), c’est à dire l’intervalle entre la première image montrant le contact entre l’extrémité inférieure de l’épiglotte et les surfaces aryténoïdes et la première image objectivant la fin du contact. Les aspirations et les pénétrations ont été coté en utilisant une échelle de 1 à 8 , alors que les stases pharyngées ont été cotées en utilisant une pièce de cinq cents collée sur la peau du patient lors de la vidéofluoroscopie avec une échelle de 0 à 4, 0 correspondant à l’absence de stase et 4 à une stase maximale .

2.2.4

Questionnaire de qualité de vie

Tous les patients ont complété le questionnaire de qualité de vie centré sur la déglutition (SWAL-QoL). Ce questionnaire a été validé en français et est composé de 44 items sur différents aspects de la déglutition coté de 1 à 10 .

2.2.5

Protocole

Une infirmière a d’abord présenté le stimulateur au patient et à l’aide de vie à domicile. On leur a montré comment positionner le stimulateur, comment placé les électrodes sous le menton, de part et d’autre de la ligne médiane et comment mettre en route et éteindre le stimulateur. L’intensité de la stimulation a été déterminée en déterminant le seuil sensitif par incrémentation, lors de trois mesures différentes. La moyenne des trois stimulations a été calculée, l’intensité de la stimulation a été positionnée à 120 % de la moyenne. La fréquence de la stimulation électrique était de 80 Hz, la durée de 30 minutes maximum. Un repas de consistance adaptée a permis de vérifier que la technique était correctement apprise par le patient ou l’accompagnant.

Après cet étape, le stimulateur a été mis en place à la même intensité pendant la vidéofluoroscopie. Il était allumé ou éteint de façon randomisée. Trois déglutitions de purée et trois déglutition de liquide stimulateur allumé et trois déglutitions de purée et trois déglutition de liquide stimulateur éteint ont été étudiées. Les investigateurs ne savaient pas quand le stimulateur était éteint ou allumé.

Une fois que la phase d’apprentissage et de contrôle étaient bien apprises, le patient rentrait chez lui avec son stimulateur. Les stimulations électriques étaient faites lors de chaque repas pendant six semaines, pendant au maximum 30 minutes. Après ces six semaines, le patient était revu en consultation et il remplissait à nouveau le questionnaire de qualité de vie. L’observance était cliniquement notée.

2.2.6

Analyses et statistiques

Les différents temps de la déglutition pour les liquides et la purée ont été comparés lorsque le stimulateur était allumé ou éteint. Les différentes échelles du questionnaires ont été comparées avant et après les six semaines d’utilisation. Les résultats sont exprimés par la moyenne et la déviation standard, les différences ont été calculées en utilisant un test de Wilcoxon pour des données appariées. Les différences ont été considérées significatives quand la probabilité ( p ) d’erreur de type était égale ou inférieure à 0,05.

2.3

Résultats

Les caractéristiques des patients sont détaillées dans le Tableau 1 . La dysphagie était secondaire aux affections suivantes : accident vasculaire cérébral pour six patients, sclérose en plaque (un patient), maladie de Parkinson (un patient), paralysie supranucléaire progressive (cinq patients). Sur les six patients ayant eu un AVC, cinq ont eu un AVC d’un hémisphère et un patient à eu un AVC du tronc cérébral. Ils présentaient tous un handicap sévère évalué à l’aide de l’indice de Barthel. Tous les patients s’alimentaient par voie orale et présentaient une dysphagie oropharyngée modérée.