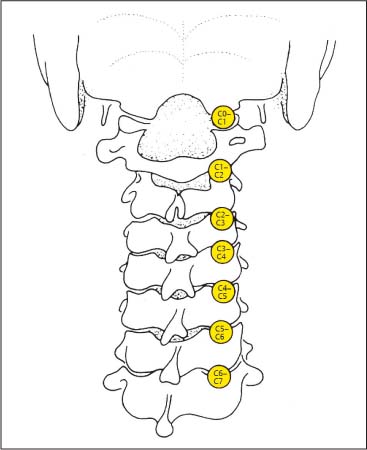

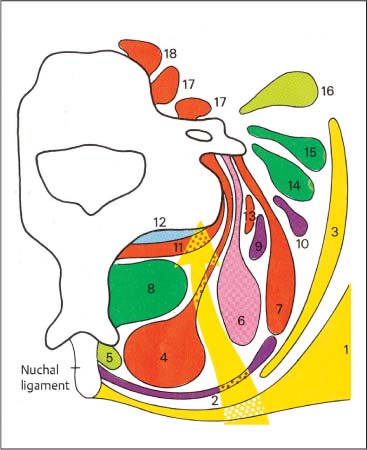

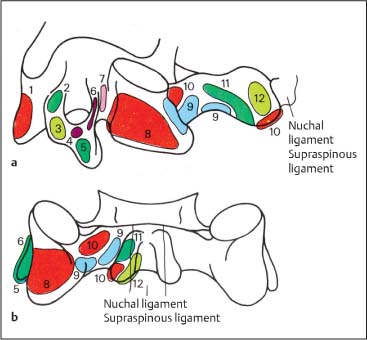

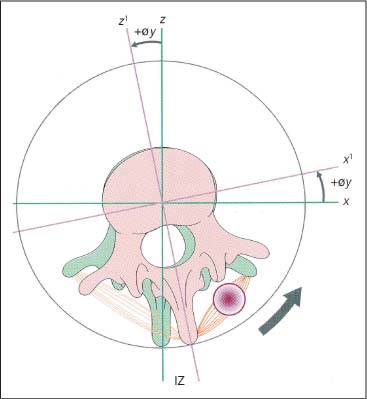

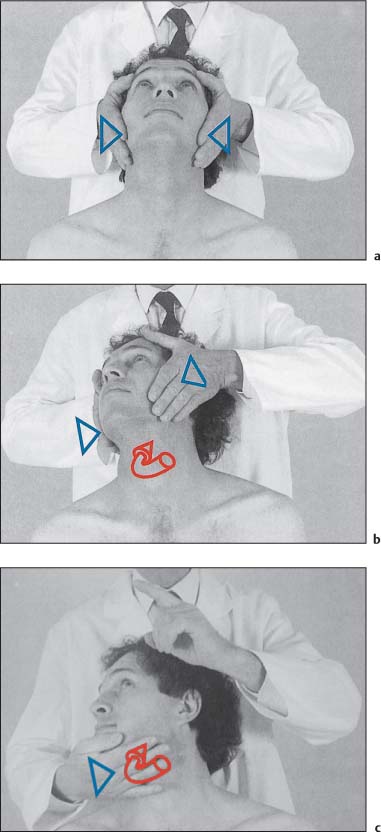

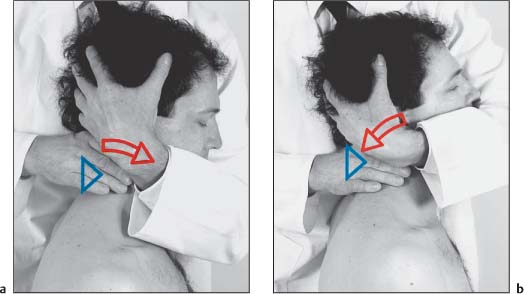

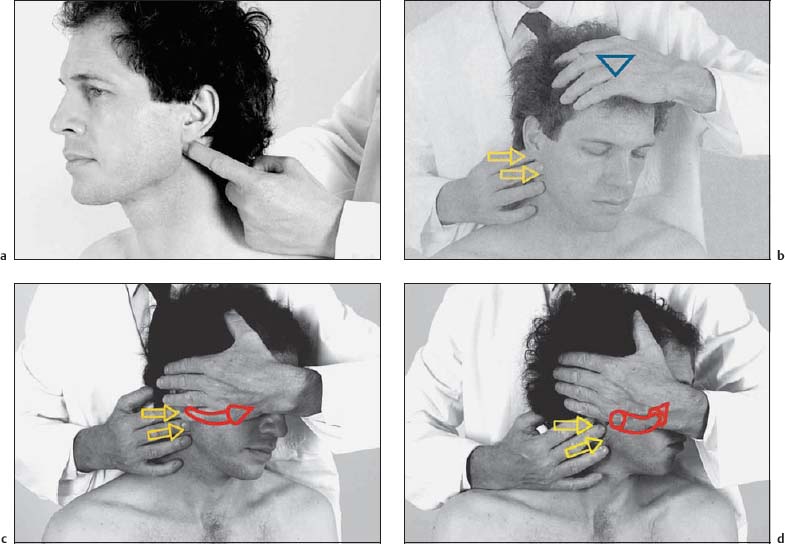

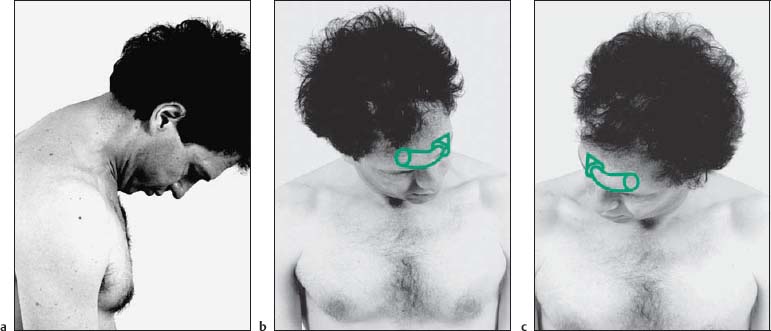

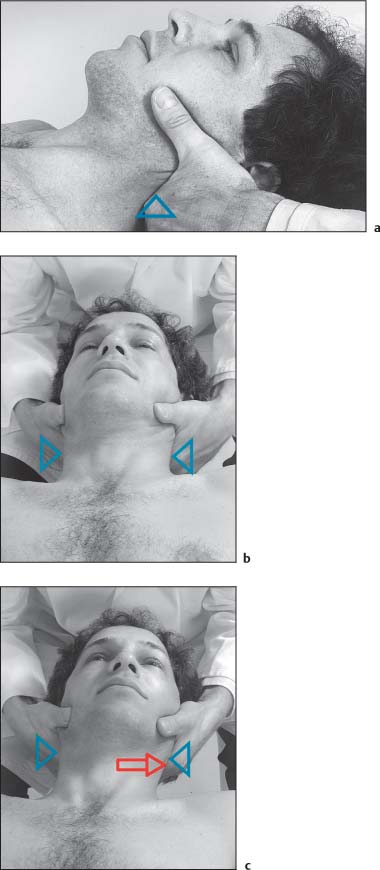

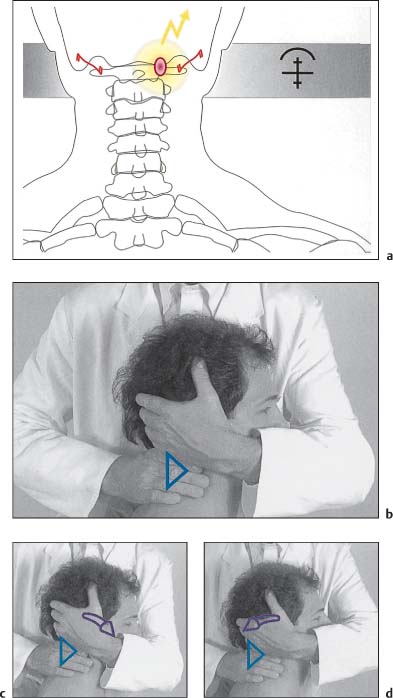

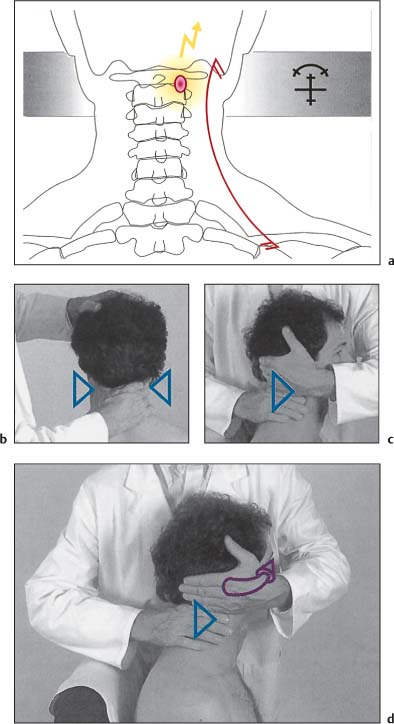

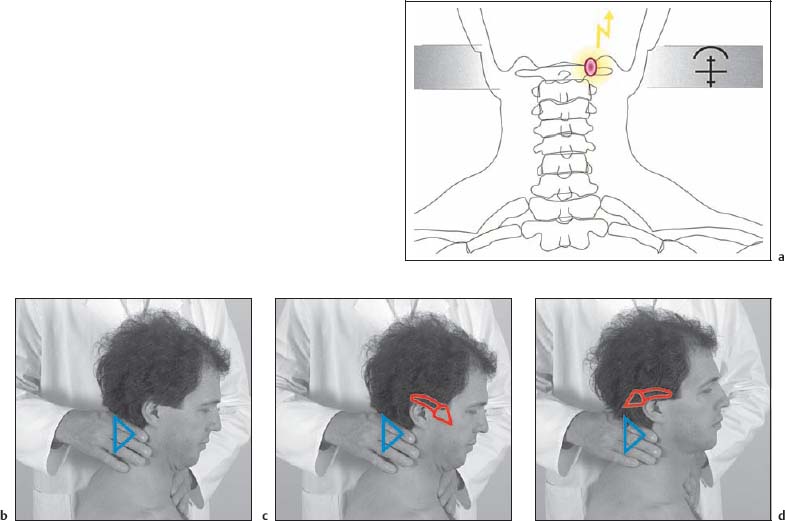

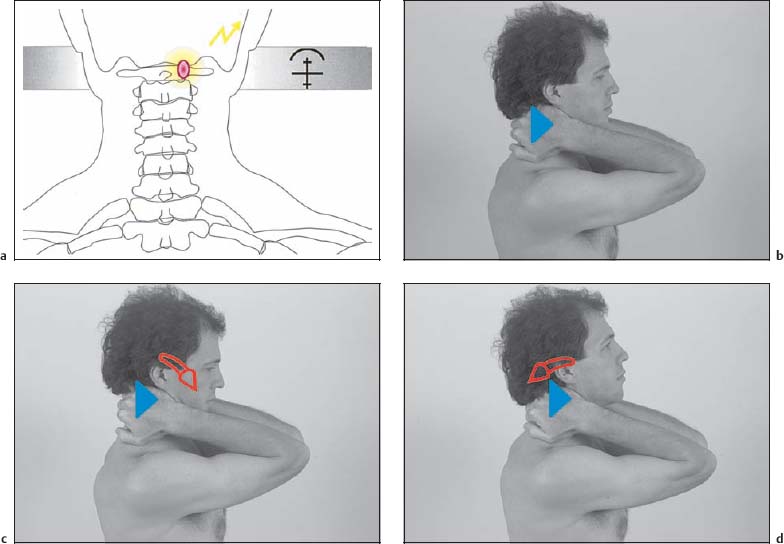

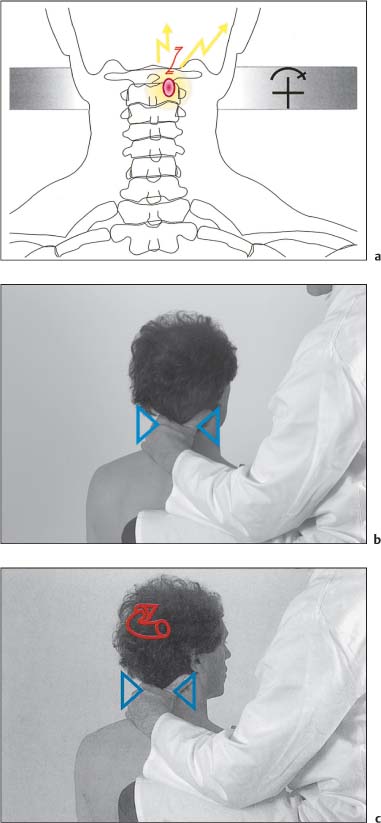

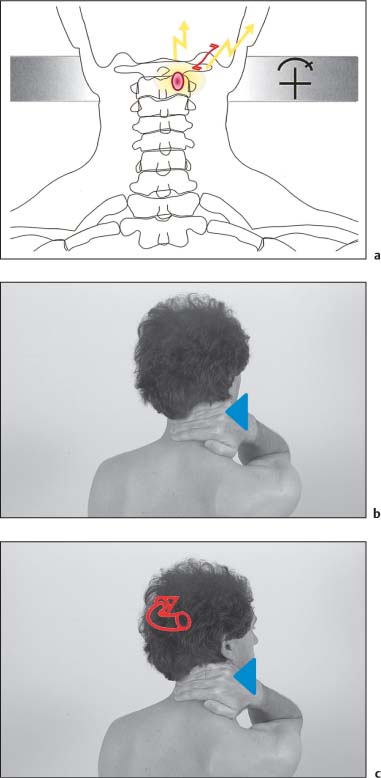

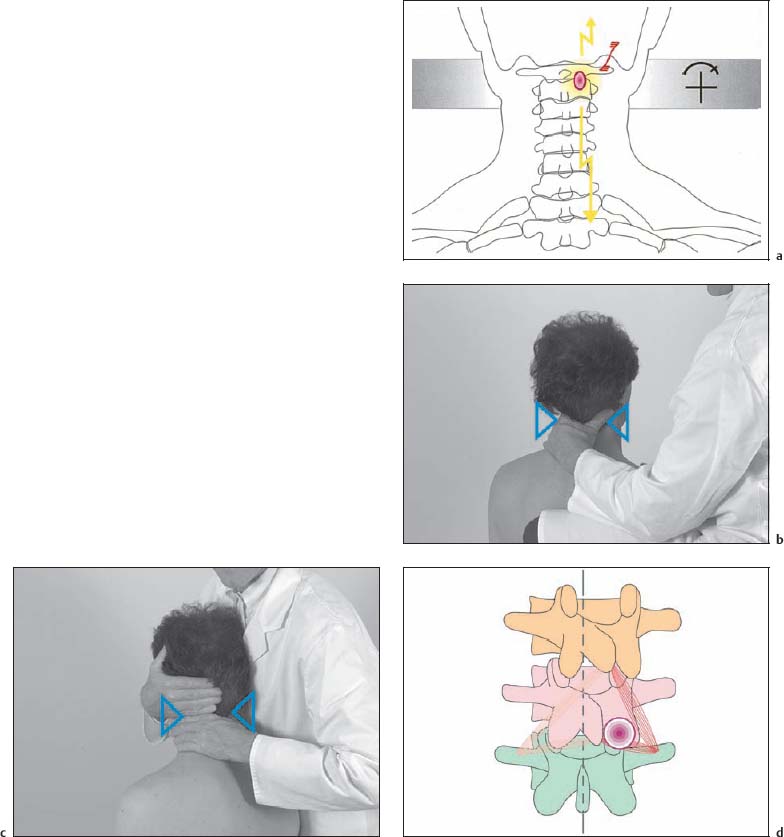

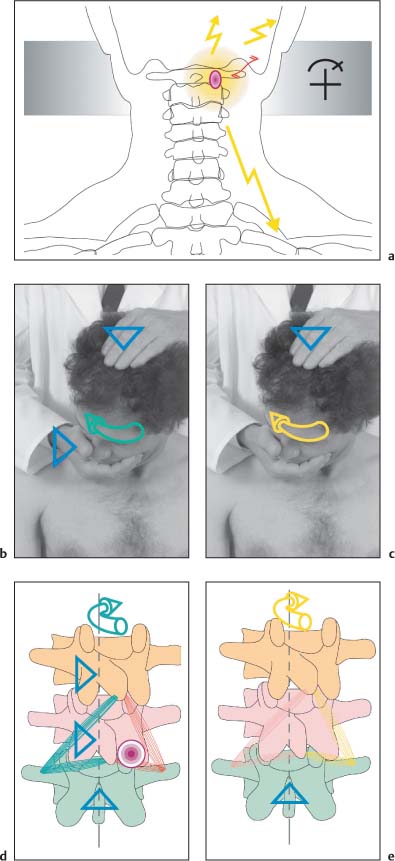

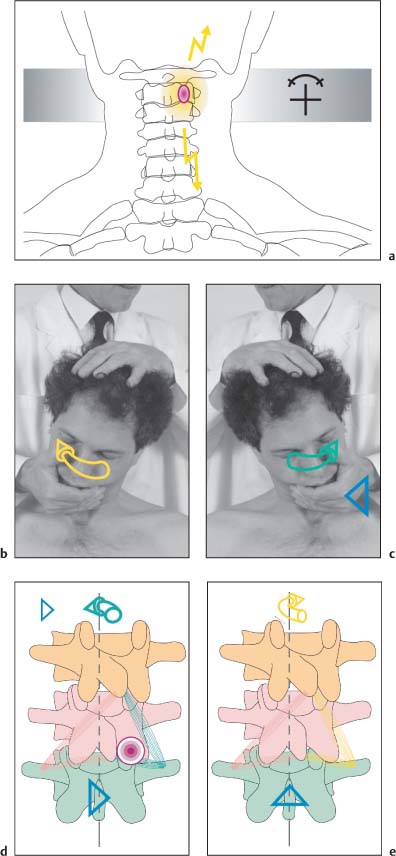

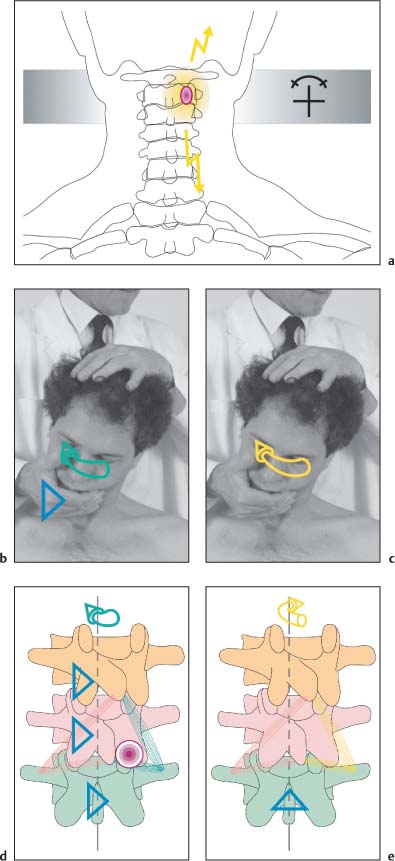

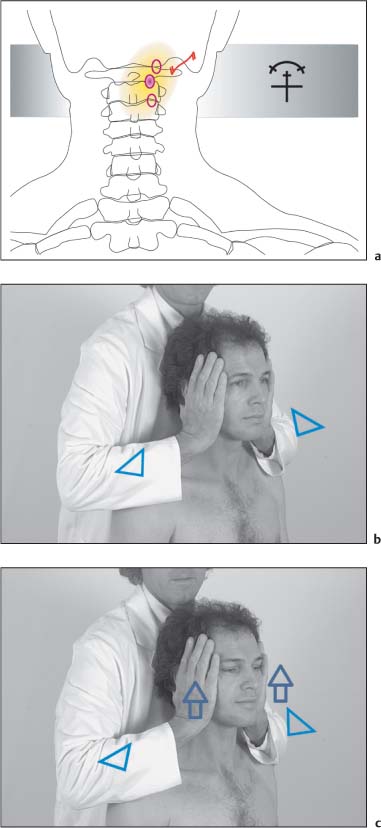

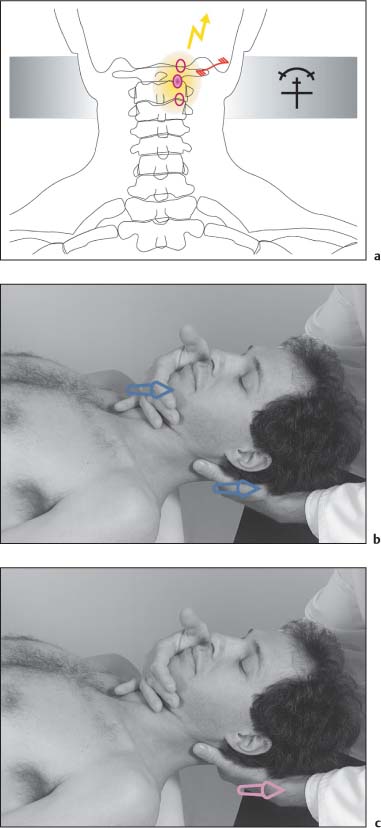

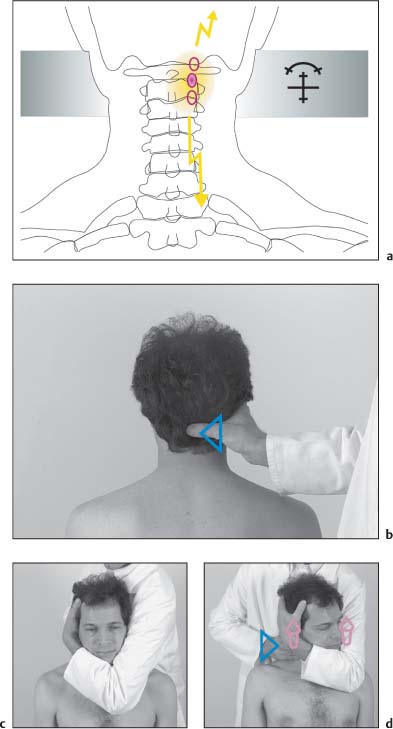

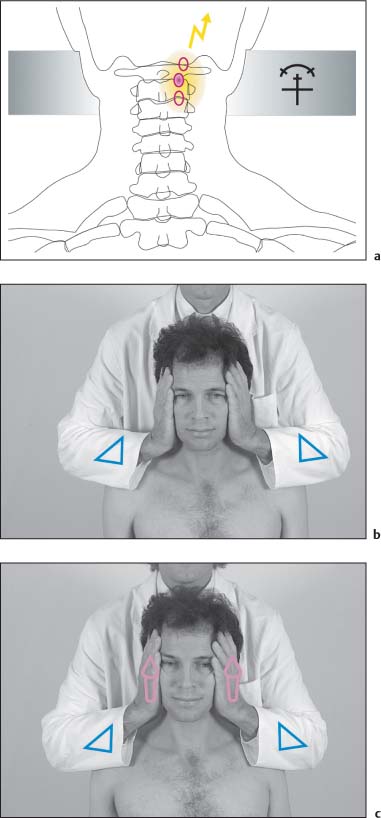

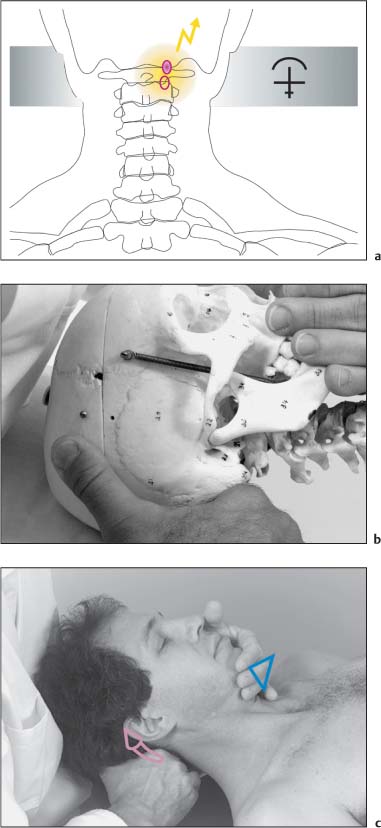

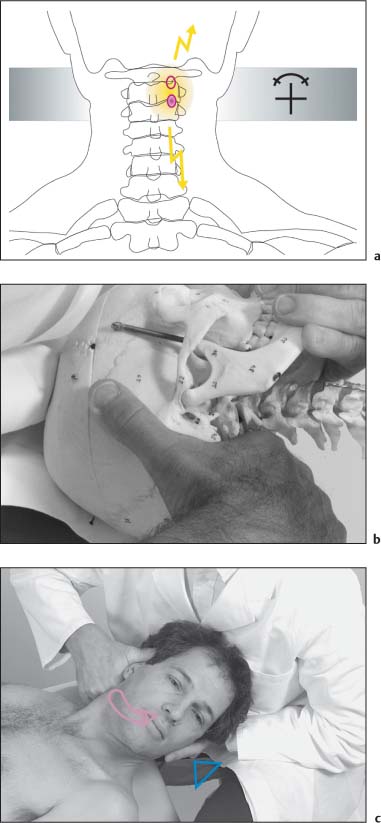

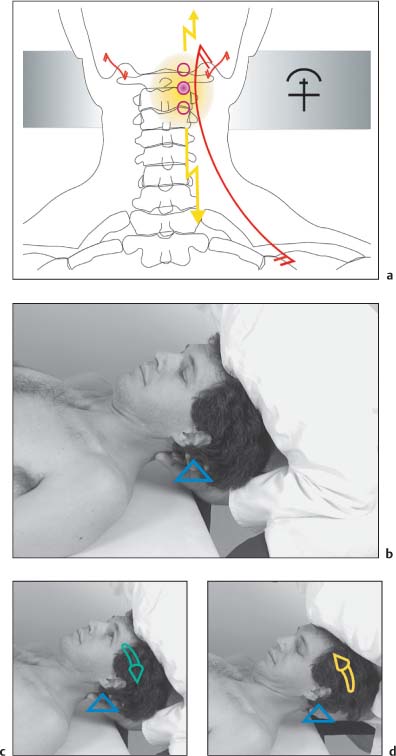

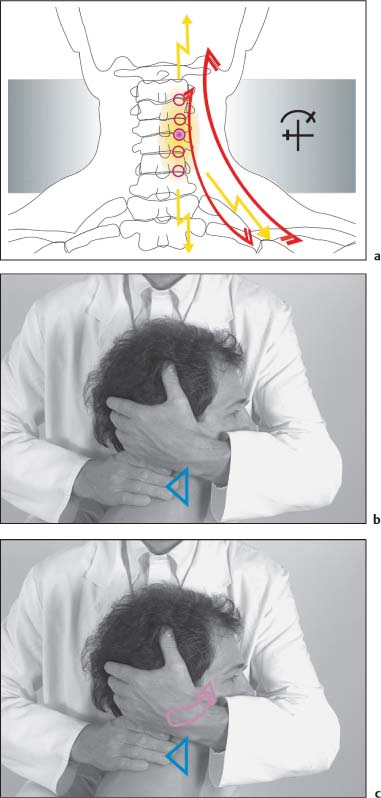

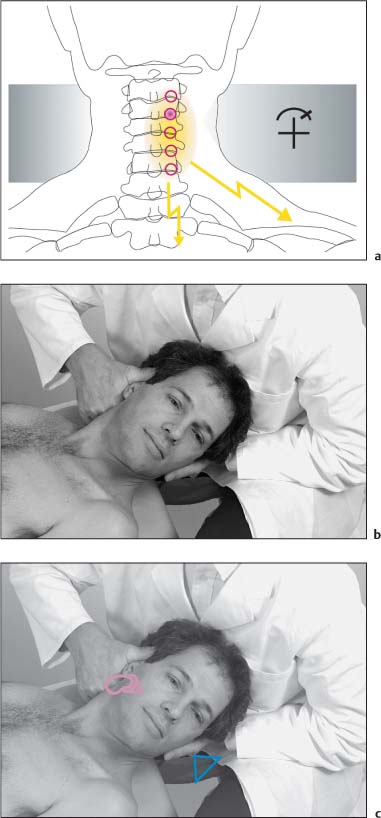

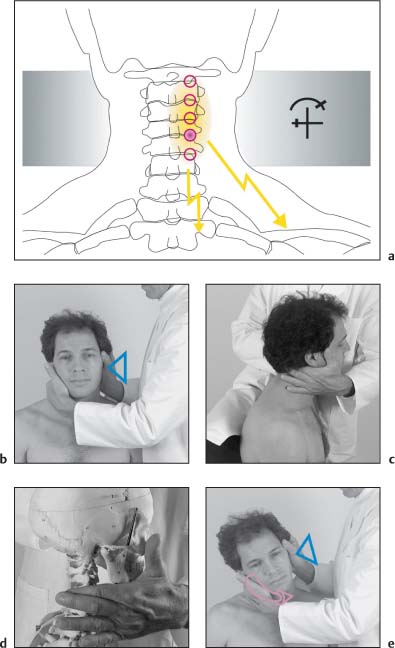

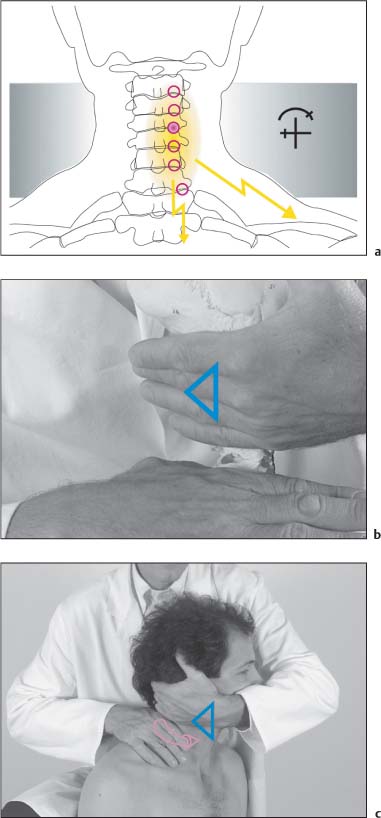

15 Structural and Functional Diagnosis and Treatment of the Spine, Ribs, Pelvis, and Sacroiliac Joint This is the most prominent bony structure at the occiput in the midline. The center point of the external occipital protuberance is specifically referred to as the inion. The superior nuchal line is palpable by following the external occipital protuberance laterally. The inferior nuchal line is located approximately 1–1½ finger-widths below the superior nuchal line. The region between the two nuchal lines is of clinical significance, as this is the region of insertion of the semi-spinalis capitis muscle. This area is accessible to palpation. Palpation of the mastoid begins with gently placing the finger just behind the ear. The palpating finger then descends toward the tip of the mastoid process. Starting from the medial portion of the tip, the finger is moved superiorly to the upper pole of the mastoid sulcus, an important area in the evaluation of the irritation zones for C0 and C1. Starting from inferior, this bony landmark is palpated by placing the finger in the area between the mastoid process and the descending ramus of the mandible. Due to anatomic variations and the overlying muscles, it is not always easy to palpate the transverse process of the atlas. In some cases, palpation may be very painful (insertion tendinoses) and should always be performed gently. It may be beneficial to palpate both transverse processes simultaneously. Due to the various muscles in this area and the deep location of the atlas, palpation of the lateral portion is possible only in a limited number of patients and is therefore dependent on the individual’s anatomy. This is the first prominent bony landmark routinely accessible to palpation below the occiput. The palpating finger localizes the external occipital protuberance first and then moves inferiorly along the midline until it meets the protruding spinous process of C2. Localization of C6 and C7 is important for exact segmental level determination and is usually best accomplished by introducing passive flexion and extension to the cervical spine. The most prominent vertebra is not always C7 as on occasion C6 or T1 may be the most conspicuous one. The superior joint surfaces of C7 are still relatively flat (more horizontal), whereas its inferior joint surfaces show an arrangement resembling that of a thoracic vertebra. This explains why during maximal neck extension the cervical vertebrae, except for C7, should move deep or away from the palpating hand. This clinical observation is an important criterion for exact level localization at the cervical spine. Fig. 15.1 Bony landmarks at the occiput and the posterior cervical spine. This IZ associated with C0–C1 articulation is found on either side of the midline at the level of the occipitoatlantal joint. A segmental or somatic dysfunction involving this articulation is usually accompanied by an IZ, typically on the same side as the dysfunction. Differentiation from surrounding tendinoses is only possible with the help of provocative examination maneuvers (see below). The C0–C1 IZ may be palpable at the lateral aspect of the transverse process of the atlas. In the clinical setting, it may not be easy to differentiate an IZ from tendinoses of muscles that have their attachments in the upper cervical spine and at the occiput. Clinically useful irritation zones are those that are associated with the facet joints between the level of the axis and the C6 vertebra (C1–C2 through C5–C6, respectively). The IZ associated with each articulations is located at the surface projection overlying the incriminated facet joint. In locating the IZ, palpation starts by first localizing the spinous processes in the following manner. The index finger of one hand is placed over the spinous process of C2 while the middle finger comes to rest over spinous process of C3, the ring finger over the C4 vertebra, and the small finger over spinous process C5. From this position, the fingers slide laterally until they reach the groove formed by the semispinalis capitis and longissimus capitis muscles (Figs. 15.2, 15.5). From there, the fingers are advanced carefully until they can palpate the slight protuberance of the superior articular pillar (Fig. 15.3). While a rather straightforward maneuver, some caution is needed, as this area can be painful to the patient if too much pressure is applied. In the neutral position, the superior articular pillar of C2 is located one finger-width below the occiput and about one finger-width superior to the inferior edge of the spinous process of C2. The superior articular pillars of C3 and C4 are each one finger-width more inferior, respectively. With maximal extension of the head, the IZ of C4 is located at the lowest point of the concave cervical spine, whereas that of C5 is 1.5 finger-widths below that of C4. The IZ of C6 is one finger-width below that of C5 (Fig. 15.4). During the examination, the examiner stands behind and to the side of the patient. Since the head of the seated, relaxed patient can be guided in any direction with the physician’s nonmonitoring hand, joint play of the cervical facet joints can easily be assessed, providing additional and specific information about each segmental motion behavior. The IZ must, however, be differentiated from painful muscles that attach at the particular pillars (Fig. 15.6). Fig. 15.2 Palpation of the irritation zones in the posterior cervical spine. Fig. 15.3 Palpation of the irritation zones in the posterior cervical spine at the level of the articular pillars. Fig. 15.4 Location of the different irritation zones in the posterior cervical spine. Fig. 15.5 Cross-section at the mid-cervical spine level. Palpatory access is demonstrated by the arrow (according to Sutter). 1 Trapezius muscle 2 Splenius capitis muscle 3 Sternocleidomastoid muscle 4 Semispinalis muscle 5 Interspinalis muscle 6 Longissimus capitis muscle 7 Levator scapulae muscle 8 Semispinalis cervicis muscle 9 Longissimus cervicis muscle 10 Splenius cervicis muscle 11 Multifidus muscle 12 Rotator muscles 13 Iliocostalis cervicis muscle 14 Posterior scalene muscle 15 Middle scalene muscle 16 Anterior scalene muscle 17 Longus capitis muscle 18 Longus colli muscle Fig. 15.6a, b Major muscle origins and insertion at the mid-cervical level (according to Sutter). 1 Longus colli muscle (inferior portion) 2 Anterior cervical intertransverse muscle 3 Anterior scalene muscle 4 Posterior cervical intertransverse muscle (lateral portion) 5 Medial scalene muscle Levator scapulae muscle Splenius cervicis muscle Iliocostalis cervicis muscle Longissimus cervicis and capitis muscles 6 Posterior cervical intertransverse muscles 7 Longissimus capitis muscle 8 Semispinalis capitis muscle 9 Rotator muscles, cervical region 10 Multifidus 11 Semispinalis cervicis muscle 12 Interspinous cervical muscles The IZ at C6–C7 is not easily palpated, mainly due to the presence of the strong fibers of the trapezius (descending portion) and the long back muscles. First, one localizes the transverse processes on either side, then the spinous process of vertebra C7. The latter is usually referred to as the “vertebra prominens,” even though it is not always the most conspicuous (see above). The IZ associated with the articulation of C6–C7 is located two finger-widths superior to the spinous process and about one finger-width medial to the tip of the transverse process. All of the IZs in the cervical spine region can be further evaluated by using appropriate provocation. A reported decrease in the patient’s pain or reduction in tissue tension indicates the appropriate therapeutic direction for the segment that is being examined. Note that the majority of dysfunctions in the cervical spine occur in the posterior direction, that is, the extended position. In this case, the IZ would be exacerbated as one introduces additional cervical spine extension (posterior motion). In contrast, the induction of flexion motion to the particular joint would typically be associated with a decrease in the IZ and/or a reduction in tissue texture abnormality (Fig. 15.7). While maintaining constant but slight pressure, the index or middle finger localizes the incriminated IZ. Appropriate pressure is that with which the patient can just barely notice the pain. The other hand is placed over the patient’s parietal region of the head to introduce rotation to the cervical spine to either side in a controlled manner allowing isolation of spinal segments individually (Figs. 15.8, 15.9). Fig. 15.7 Provocation testing. Fig. 15.8 Provocation testing in the cervical spine: step 1. Localize the incriminated IZ by carefully approaching the IZ on the right. Fig. 15.9 Provocation testing in the cervical spine: step 2. Introduce rotation to the left and right and localize the forces to the IZ for side-to-side comparison. • Starting in the neutral position (a), the seated patient is requested to actively perform movements of flexion (b), extension (c), rotation to the left (d) and to the right (e) and finally lateral bending (side-bending) to the left (f) and to the right (g). The examiner evaluates symmetry, quantity, and quality of range of motion, and the occurrence of any substituted or abnormal movements. 1. Generalized loss of motion without pain at the extreme of the movement or at the motion barrier is more indicative of degenerative problems. At the time of the examination, this finding is of less crucial importance. In contrast, pain that is elicited with movement, either during or at the end of the introduced motion, must be further investigated. 2. Vertigo that appears immediately with movement and disappears rapidly is more likely to be due to cervicalspondylogenic causes. Vertigo of the crescendo type is more indicative of peripheral or central-vestibular disturbances. 3. An isolated finding of restricted side-bending is often due to underlying spondylosis affecting the uncovertebral joints. • For passive motion testing, the seated patient leans against the physician’s thigh. Starting from the neutral position (a), the physician introduces passive flexion (b) and extension (c) to the cervical spine with one hand placed on the patient’s vertex. • Subsequently the physician stabilizes the patient’s shoulder with his other hand and then introduces cervical spine rotation to the left (d) and to the right (e), followed by lateral bending (side-bending) to the left (f) and right (g). 1. Generalized loss of motion without pain at the extreme of the movement or at the motion barrier is a possible indication of degenerative changes in the incriminated facet joints or spinal column, e. g., spondylosis. The mere presence of spondylosis may or may not have any impact on the patient’s current pain state. In contrast, pain that is elicited with carefully guided movement, either during or at the end of the introduced motion, calls for further investigation. 2. Vertigo that appears immediately with movement and disappears rapidly is more likely to be due to cervicalspondylogenic causes. Vertigo of the crescendo type is more indicative of peripheral or central-vestibular disturbances. 3. An isolated finding of restricted side-bending is often due to underlying spondylosis affecting the uncovertebral joints. • The patient is seated with the thoracic spine held as straight as possible. With either hand placed over the patient’s parietal region, the examiner introduces passive cervical extension (a). • Through this maneuver, the upper cervical spinal joints (C0–C2) are maximally extended, that is reclinated and thus stabilized by the action of the alar ligaments, which in this position are rather taut. • The passive introduction of rotation to the head coupled with mild cervical spine side-bending now introduces rotation primarily to the joints below the upper cervical spine all the way to the cervicothoracic junction (b and c). • “Normal” empirically determined values for rotation in cervical extension have been reported to measure approximately 60° to either side (Caviezel, 1976; Lewit, 1970). 1. Decreased range of motion with hard end-feel. Degenerative changes that occur with great frequency in the mid-cervical spine, including spondylosis, spondyloarthopathy, and arthrosis, may cause motion restriction with a hard end-feel. 2. Decreased, range of motion with soft end-feel. This is most likely the result of shortened long neck extensor muscles. 3. Pain. Pain may be the result of segmental somatic dysfunction. 4. Vertigo and other autonomic signs or symptoms. These suggest a diminished blood supply or a possible irritation of the vertebral artery (refer to the provocation testing described for the vertebral artery, next page). • The patient is seated. While the examiner’s hand rests on top of the patient’s head, the cervical spine is first passively reclinated (= extension at C0 through C2) or extended (C3–C4 through C7) (a) and then rotated (b). The patient is then requested to look in the opposite direction while focusing on the examiner’s index finger. The examiner looks for the presence of nystagmus in order to exclude the possibility of a latent type of nystagmus. The patient should remain in the described position for at least 20–30 seconds (c). • If during any part of the examination the patient begins to complain of vertigo or nausea or if the physician observes any signs of nystagmus, the examination procedure should be terminated promptly. 1. Gradually progressive vertigo that is reported during the positioning maneuver either in the presence or in the absence of nystagmus may be indicative of peripheral, central, or vestibular disturbance, or a combination thereof, resulting form a potential reduction in circulation through the vertebral artery. 2. Vertigo that appears at the beginning of the examination but improves during the procedure and may occasionally be accompanied by spontaneously resolving nystagmus may be more indicative of either cervical vertigo or cervicogenic nystagmus, or both. However, clinical interpretation is often not clear-cut, and it would in most cases be advisable to refer the patient to the appropriate medical specialist, such as a neuroophthalmologist or otoneurologist. • While in the seated position, the patient is requested to perform flexion (a) and extension (b) movementsin the upper cervical spine (C0–C1–C2–C3) articulations, movements that have specifically been termed as inclination and reclination motions, respectively. These particular movements require the examiner to give precise instructions to the patient, since only the joints of the upper cervical spine should be engaged. These movements are different from the more generalized flexion/extension movements in the remainder of the cervical spine. One of the practical instructions for the patient is to perform a “small nodding motion, like a small ‘yes’”), the inclination movement, that is, the specific flexion motion in the upper cervical spine, represents a backward nutation motion. With this movement, the occipital condyles move posteriorly on the atlas while the atlas is displaced anteriorly on the axis. • During the reclination movement (specific extension movement in the upper cervical spine, that is, nodding” the head backward), the occipital condyles glide anteriorly on the atlas, which itself in turn is being displaced posteriorly upon the axis. 1. Decreased range of motion during inclination or reclination with hard or soft end-feel. A hard end-feel is most likely associated with articular or structural degenerative joint changes, whereas a soft end-feel, together with decreased range of motion is most likely due to shortened suboccipital muscles. 2. Suboccipital pain either with movement or at the extreme of movement at the motion barrier. This may indicate a somatic dysfunction, but the possibility of C0–C3 instability must be included in the differential diagnosis. Potential inflammatory changes in this upper cervical spine should be further investigated, if clinically indicated • In this passive examination, the examiner cradles the patient’s head with one hand. Using the index finger and the thumb of the other hand, the examiner then fixates (stabilizes) the axis and therefore the vertebrae below. It is important to remember that the fixating forces are directed toward the articular processes only, so that the soft tissues, in particular the muscles, are not compressed during this procedure. Poor localization of forces often causes pain, limiting the conclusions that can be drawn from the findings elicited with this examination. • Inclination (a) and reclination (b) movements are tested passively in sequence. Range of motion, which is 15–20° in the normal adult, is of particular interest here. Pain at the end of motion should also be noted. 1. Decreased range of motion either during inclination or reclination with hard or soft end-feel. A hard end-feel is most likely associated with articular (structural) degenerative changes, whereas a soft end-feel, together with decreased range of motion, is probably due to shortened suboccipital muscles. 2. Suboccipital pain either with movement or at the end of movement. This may indicate a somatic dysfunction, but the possibility of C0–C3 instability must be included in the differential diagnosis; inflammatory changes in this area of the spine must also be excluded. 3. Autonomic symptoms may be reported by the patient. It is important that these be further investigated, especially when accompanied by complaints of vertigo. • The patient sits. The physician places his middle finger at the level of the transverse process of the atlas (a) and the index finger over the mastoid process (b). • With his other hand the physician introduces passive maximal rotation to the cervical spine (c). When approaching the motion barrier there should be a “springy” sensation of motion between the occiput and the atlas (d). • The distance between the transverse process of the atlas and the mastoid process is progressively reduced as the motion barrier is approached. This distance is then compared on one side with that on the opposite side, which gives some indication about the extent of the patient’s rotation between occiput and atlas. 1. There is no “springy” motion when approaching the motion barrier. This functional hypomobility may indicate involvement of the C0–C1 articulation. 2. Pain or vertigo is reported by the patient during the evaluation maneuver. This should raise the suspicion of cervical spinal dysfunction (somatic dysfunction), or if there is vertigo, there may be vertebral artery involvement. • The patient is either seated or supine. The index finger of either of the examiner’s hands localizes the transverse processes of the atlas on either side. With his other hand, the physician cradles the patient’s head. Examining one spinal segment at a time, passive side-bending is introduced to the left (a) and to the right (b), thereby evaluating the ease of side-to-side gliding (a). There is some, albeit very small, lateral displacement of the occipital condyles on the joint surfaces of the atlas in the direction opposite to the induced side-bending. • In the next step of this maneuver, the atlas is fixated by the physician while left and right side-bending motions are introduced. 1. The atlas does not glide in the same direction as side-bending or, paradoxically, even moves in the direction opposite that of side-bending. This may indicate a segmental somatic dysfunction as well as instability. 2. When starting from the patient’s “normal” neutral position, passive side-bending does not take place. If the head is excessively extended (reclined), for instance, paradoxical gliding movement may take place. • The seated patient is requested to maximally flex his neck, including maximal inclination at the C1–C2 portion. The lower cervical spinal segments are “locked” in maximal flexion, that is, they are brought into their extreme or end position, thus allowing rotation to occur only in the upper cervical spine, namely between C1 and C2 (a). • The patient is subsequently requested to turn the head from the left (b) to the right (c). 1. Decreased rotation with hard or soft end-feel, in combination with neck pain. A hard end-feel may indicate articular (structural) degenerative changes, whereas a soft end-feel is more likely associated with shortened suboccipital muscles. 2. Vertigo at the extreme or end position of rotational movement. This requires further work-up for causes of the reported vertigo, including the possibility of vertebral artery compromise. • The physician stands behind the patient in such a manner that the patient is able to comfortably rest his thorax against the thigh of the examiner. Passive motion testing for C1–C2 is introduced by the operation, which exaggerates the normal thoracic kyphosis and flexion at the cervicothoracic junction. The examiner places one hand over the parietal region of the patient’s head and gently introduces flexion to maximum (a). • The other hand, cradling the patient’s chin, introduces rotation with slight side-bending to the left (b) and to the right (c). The induced motion should follow along the lines of the clavicles. • Normal range of motion is between 40° and 45° to either side. 1. Decreased rotation with hard or soft end-feel, in combination with neck pain. A hard end-feel may indicate articular (structural) degenerative changes, whereas a soft end-feel is most likely associated with shortened suboccipital muscles. 2. Vertigo at the extreme or end position of rotational movement. This requires further work-up for causes of vertigo, including the possibility of vertebral artery compromise. • The head of the seated patient is cradled by one of the examiner’s arms in such a manner that the forearm supports the facial bones and the hypothenar eminence, while the small finger rests on the transverse process of the atlas. The index finger and thumb of the other hand gently fixate (stabilize) the axis (a). • The examiner introduces rotational movement to the head (passive rotation), which is accompanied by anterior and posterior gliding movements at these spinal segments (b). 1. Decreased angular range of motion or diminished joint play, either with hard or soft end-feel. A hard end-feel is most likely due to articular (structural) degenerative changes, while a soft end-feel is usually associated with shortened suboccipital muscles. 2. Vertigo during the procedure. This should raise the suspicion of cervical spine instability, changes in the vertebral artery blood flow, or inflammatory processes affecting the upper cervical spine. 3. Pain in conjunction with introduced motion indicates a segmental somatic dysfunction. • With the patient sitting, the examiner places an index finger over the spinous process of the axis and a middle finger over the spinous process of C3 (a). The other hand is placed at the patient’s parietal region so that rotation (b) and side-bending to either side (c and d) can be introduced. • The moment the side-bending is introduced, the axis begins to rotate, typically in the same direction as that of side-bending (the spinous process rotates in the opposite direction). • In contrast, due to the noted coupling pattern between the occiput and the axis, the first cervical vertebra does not begin to rotate immediately upon the introduction of head rotation, but does so only after about 20–30° of head rotation. 1. Forced rotation of the axis during side-bending may be absent due to lesions of the ligaments, in particular the alar ligaments; for differential diagnosis the possibility of segmental instability should be considered. 2. If the axis begins to rotate immediately upon cervical spine rotation, it may be due to a segmental dysfunction at the C1–C2 spinal segment, usually indicative of a functional motion restriction (somatic dysfunction). • The patient is sitting. The physician introduces optimal passive inclination motion to the upper cervical spine, that is to the first three cervical vertebrae. Once in this position, the posterior ligaments, in particular the ligamentum nuchae, the physician tilts the atlas anteriorly, which reduces rotation between C1 and C2 to a minimum. • The physician then places his stabilizing hand over the patient’s parietal region and introduces slight side-bending to the head, which takes up the slack in the vertebral segments distal to C3. • The other hand then cradles the patient’s chin and introduces further inclination and rotation to the left (a) and to the right (b). This maneuver should be performed carefully and gently while the chin is held close to the neck. • The normal range of motion is 10–15°. Reduced range of motion while the chin is tucked indicates a somatic (segmental) dysfunction at the C2–C3 level. • The patient is in the supine position. The examiner palpates the patient’s transverse process on either side with each middle finger, while the index finger rests over the mastoid process (a). • While simultaneously introducing longitudinal traction, the patient’s head is shifted (translatory movement) to the left (= side-bending right) (b) and then to the right (= side-bending left) (c) side. 1. Increased resistance (or decreased resiliency) during the translatory side-to-side movement. 2. Lack of translatory motion with hard or soft end-feel, or both. • Standing behind the seated patient, the examiner places four fingers over the spinous processes in the mid-cervical spine and then the cervicothoracic junction (a). Motion to the cervical spine is introduced by the physician using the other hand, which is placed on the patient’s vertex. The following movements are then introduced by the physician in sequence: 1. Flexion (a) followed by extension (b). 2. Rotation to the left (c) followed by rotation to the right (d). 3. Side-bending to the left (e) followed by side-bending to the right (f). Note: The sequence as to the side on which the motion is introduced depends on physician preference. Thus rotation may be introduced to the right first, and so forth. There is noticeable asymmetry in the segmental range of motion palpated as a result of segmental somatic dysfunction or abnormal coupling patterns. • The index finger and thumb of the monitoring hand palpate the area over the facet joints, making as much contact with the bony structures as possible (a). Care must be taken, however, not to press on the soft tissues too forcefully, especially those muscles overlying the bone. Entry to the articular processes in this area is between the semispinalis capitis muscle and the long-issimus capitis cervicis muscle (see Irritation Zones (IZ) Associated with the Cervical Spine, p. 332). The examiner’s guiding hand is placed over the vertex of the patient’s head, and then the following passive motions are introduced: – Flexion (lower hand stabilizes) (b) – Extension (upper hand stabilizes) (b). – Side-bending (c). – Rotation (d). • The examiner determines whether movement of the facet joints is symmetrical, in particular if the joints “open” and “close” symmetrically with the respective movement. 1. Asymmetric joint motion during the individual movements are most likely due to a segmental somatic dysfunction. This examination plays a cardinal role in the segmental diagnosis. 2. Pain that is exacerbated with movement may well be the result of a segmental irritation zone. • With the patient in the supine position, the examiner palpates the area over the facet joint in question (a and b). • The palms of the examiner’s hands are placed to either side of the patient’s occipitotemporal region. While longitudinal traction is being carefully introduced, the examiner performs a translatory side-to-side movement for each individual joint pair; that is, segments are evaluated one at a time by translating the individual vertebrae from the right to the left (c), thus introducing side-bending to the right in this instance. Note: Not shown is the same motion testing for left side-bending motion, in which case the physician performs a translatory motion starting from the left side by introducing a pure left-to-right motion component force toward the right side at each vertebral level. Movement is asymmetrical, that is, side-to-side movement is “easier” in one direction than the other. A hard end-feel is most likely due to structural or degenerative changes in the joint itself. • Pain: Acute or chronic; typically localized to the suboccipital region, but the pain may also radiate further cephalad up the back of the head (a). • Irritation zone: C0–C1. • Motion testing: Inclination and/or reclination restriction with hard end-feel; inclination denotes the flexion motion at C0–C1, and reclination denotes the extension motion at C0–C1. • Muscle testing: Shortened suboccipital muscles. • Autonomic signs/symptoms: Nonsystematic vertigo, which may be exacerbated by palpatory pressure (a). • The patient is seated. • The patient’s cervical spine is guided to its anatomic neutral or present neutral position. • The C0–C1 spinal segment is engaged at its pathologic barrier. • C2 is fixated at either articular pillar through the physician’s thumb and index finger. • The patient’s head is held stationary (fixation) by the physician as follows: one hand is placed flat over the temporal region while the other side of the head comes to rest against the physician’s chest (b). • Passive mobilization is introduced to improve inclination (flexion) (c) and reclination (extension) (d) at the C0–C1 spinal segment. Note: With induced reclination motion the associated coupled movement is in an anterior direction; with induced inclination motion the associated coupled movement is in a posterior direction. A mobilization technique well suited as a preparatory technique for both the appropriate NMT procedures and self-mobilization. If a patient reports dizziness or a feeling of “spinning” sensation during the maneuver, consider the following possibilities: • Excessive mobilization force (e. g., too high or too fast for the patient). • Excessive pressure at the irritation zone. • Atlantoaxial instability (e. g., chronic polyarthritis, status post trauma). • Vascular abnormalities. • Pain: Pain can be either acute or chronic. Primarily pain is reported in the neck region but it may also radiate to the temporal area (a). • Irritation zone: C1–C2. • Motion testing: C1–C2 segmental rotation restriction, occasional inclination–reclination restriction with hard or soft end-feel. • Muscle testing: The levator scapulae and/or the descending portion of the trapezius muscle may be shortened (a). • The patient is seated. • The physician places his thumb and index finger over the articular processes of C2, thereby fixating the vertebra (b). • The physician embraces the patient’shead with one arm such that the small finger and the metacarpal bone of the small finger come to rest over the occiput and C1 (c). • The cervical spine is guided to its present neutral position. The incriminated segment is engaged at its pathologic barrier. • Passive mobilization is introduced with the primary goal of improving the rotation motion to this spinal segment. At the same time, the patient is requested to direct his gaze following the direction of rotation movement (d). • The individual mobilization step is rather small. Some carefully dosed traction should be applied to the cervical spine as well when performing this maneuver. • Excessive force must be avoided so as to prevent potential compression of the vertebral artery. • If the patient reports vertigo during this maneuver, treatment should be terminated immediately. • If vertigo becomes manifest during the patient positioning phase, one might want to resort to the NMT 2 technique. This would address the levator scapulae muscle or the descending portion of the trapezius muscle. Naturally, the various contraindications must be excluded first. • Pain: Chronic, suboccipital region with the pain sometimes radiating further cephalad to involve the entire occiput and/or to the temporal region (a). • Irritation zone: C0–C1. • Motion testing: Segmental motion restriction (hypomobility) with restricted inclination (flexion)–reclination (extension) motion at C0–C1; soft or hard end-feel. • The patient is seated. • The cervical spine is guided to its neutral position or present neutral position. • NMT1: the incriminated spinal segment is gently fixated at the level of the arch on one side with physician’s thumb and with the index finger on the contralateral side (b). • The patient is requested to slowly and carefully move his head forward and backward in a small nodding motion localized to the upper cervical spine in order to introduce well localized flexion (inclination [c]) and extension (reclination [d]) motion at the C0–C1 articulation. • The patient is requested to inhale when the head is tilted backward during reclination movement, and to exhale when the head is tilted forward during inclination movement. • The patient is also instructed to look toward the floor during inclination movement and to look up toward the ceiling during reclination movement. If the patient complains about vertigo, either during or after this maneuver, one or several of the following factors may be implicated: • The mobilization may have been too forceful (i. e., poor technique). • Excessive anterior pressure by the physician at the irritation zone. • The maneuver may have been performed hastily (i. e., possible hypermobilization, etc.). • Atlantoaxial instability (chronic polyarthritis, status post trauma). • Pain: Chronic; radiating toward the occiput and occasionally toward the temporal region (a). • Irritation zone: C0–C1. • Motion testing: Segmental motion restriction (hypomobility) with restricted inclination (flexion) and/or reclination (extension) motion at C0–C1; soft or hard end-feel. • The patient is seated. • The cervical spine is guided to the present neutral position. • C1 is fixated by the patient’s small fingers, and if necessary, the hyopthenar eminence (b). The remaining fingers and the thumb are placed flat over the remaining lower cervical spinal segments. The patient is instructed to gently place the tips of the fingers of one hand over the other. To ensure correct application, the patient is instructed not to interlace the fingers in order to avoid excessive anterior pulling forces (b). • The spinal segment is engaged at its pathologic barrier. Note: Fixation must be performed carefully and gently. The patient should always be reminded not to pull too aggressively in an anterior direction. See previous page, and figures c and d on this page. • Pain: Either acute or chronic; radiating to the occiput, and/or temporal region (a). • Irritation zone: C1–C2. • Motion testing: Segmental rotation restriction (hypomobility) with hard or soft end-feel. • Muscle testing: The suboccipital muscles are usually shortened (a). • The patient is seated. • The cervical spine is guided to its anatomic position or present neutral position. • The articular pillars of C2 are fixated by the physician’s thumb on one side and the index finger on the other side (vise-likehold). The thumb is of particular importance as it assists here in preventing unwanted motion (b). • The incriminated spinal segment is then engaged at its pathologic barrier. Reminder: Fixation should be as gentle as possible in order to minimize the risk of dizziness or pain. • The patient is requested to actively rotate the head under the guidance provided by the physician with the goal of improving segmental rotation. • Step-by-step, the patient moves beyond the pathologic barrier, whereby his gaze simultaneously follows in the same direction as the initiated rotation motion (c). • Jerky, abrupt to-and-fro movements should be avoided. • The path gained with each individual mobilization step is rather small. • If the patient complains about vertigo during this mobilization procedure, the physician may choose to use the NMT 3 instead. Possible causes for the appearance of vertigo may include the following: – The mobilization may have been too forceful (i. e., the result of a poor technique). – Segmental instability. – Underlying vascular abnormalities. – Excessive pressure over the irritation zone by the physician. • If, for some reason, this technique proves difficult to employ, one may want to consider a mobilization-with-impulse technique, as long as the indications and contraindications have been thoroughly evaluated. • Pain: Either acute or chronic; radiating to the occiput, and/or temporal region (a). • Irritation zone: C1–C2. • Motion testing: Segmental rotation restriction (hypomobility) with hard or soft end-feel. • Muscle testing: The suboccipital muscles are usually shortened (a). • The patient is seated. • The cervical spine is guided to the present neutral position. • C1 is fixated by the patient’s small fingers and, if necessary, the hyopthenar eminences. The remaining fingers and the thumbs are placed flat over the remaining lower cervical spinal segments. The patient is instructed to gently place the tips of the fingers of one hand over the other. To ensure correct execution, the patient is instructed not to interlace the fingers so as to avoid excessive anterior pulling forces (b). • The incriminated spinal segment is then engaged at its pathologic barrier. Reminder: Fixation should be as gentle as possible in order to minimize the risk of dizziness or pain. • The patient is requested to actively rotate his head with the goal of improving segmental rotation. • Step-by-step, the patient carefully moves beyond the pathologic barrier, whereby his gaze follows in the same direction as the initiated rotation motion (c). Reminder: Jerky, abrupt to-and-fro movements must be avoided. • The path gained with each individual mobilization step is rather small. • If the patient notices vertigo during this self-mobilization procedure, the NMT 2 technique may be substituted. However, before doing so, the possible major causes for the reported vertigo should be evaluated and corrected: – The patient may have performed the maneuver too forcefully (i. e., poor technique). – Segmental instability. – Excessive pressure exerted by the patient over the irritation zone. • Pain: Acute or chronic; localized to neck region but may be radiating to the occiput and the temporal region, as well as to the area between the shoulder blades (a). • Irritation zone: C1–C2. • Motion testing: Segmental rotation restriction (hypomobility) with soft end-feel. • Muscle testing: The suboccipital muscles are shortened. • Muscle testing: Nonsystematic vertigo, which may be exacerbated by palpatory pressure (a). • The patient is seated. The cervical spine is guided to its anatomic position or to the present neutral position. • The articular pillars of C2 are fixated by the physician’s thumb and index finger in a viselike manner (b). • The physician, standing on the side toward which the segment is to be mobilized, braces the patient’shead (c). • The cervical spine should be neither compressed nor side-bent. • The spinal segment is then engaged at its pathologic barrier (d). • The patient is requested to perform a maximal isometric contraction away from the pathologic barrier (e, f). • During the postisometric relaxation phase and without releasing the fixating force, the head and neck are passively rotated beyond the pathologic barrier (g, h). In this maneuver, the shortened rotator muscles are being stretched. Reminder: Fixation should be as gentle as possible in order to minimize the risk of dizziness or pain. • The path gained with each individual mobilization step is rather small. This technique is particularly well suited for motion restriction with soft end-feel. • If vertigo appears during or after treatment, one should consider the following possible causes: – Excessive palpatory pressure applied by the physician over the irritation zone (i. e., poor technique). – The mobilization maneuver was excessively forceful during the postisometric relaxation phase. • Pain: Acute or chronic; localized to neck region and may be radiating to the occiput and the temporal region, as well as to the area between the shoulder blades (a). • Irritation zone: C1–C2. • Motion testing: Segmental rotation restriction (hypomobility) with soft end-feel. • Muscle testing: The suboccipital muscles are shortened. • Muscle testing: Nonsystematic vertigo, which may be exacerbated by palpatory pressure (a). • The patient is seated. The cervical spine is guided to its anatomic position or to the present neutral position. • The articular pillars of C2 are fixated by the physician’s thumb and index finger in a viselike manner (b). • The physician, standing on the side toward which the segment is to be mobilized, braces the patient’s head (d). • The cervical spine should be neither compressed nor side-bent. • The spinal segment is engaged at its pathologic barrier • The patient is requested to perform a maximal isometric contraction toward the pathologic barrier (e, f). The patient is instructed to inhale while performing this maneuver. • The incriminated joint is then being mobilized passively by the physician. The new pathologic barrier is subsequently engaged (g, h). Note: It is of paramount importance that the hand placement and execution of the technique are done very carefully and gently so as minimize the risk of inducing or exacerbating the patient’s pain. • The path gained with each individual mobilization step is rather small. This technique is particularly well suited when there is motion restriction with a soft end-feel. • If vertigo appears during or after treatment, one should consider the following possible causes: – Excessive palpatory pressure applied by the physician over the irritation zone (i. e., poor technique). – The mobilization maneuver may have been too forceful during the postisometric relaxation phase. • Pain: Acute or chronic; localized to the neck region; may be radiating to the occiput and the temporal region, as well as to the area between the shoulder blades (a). • Irritation zone: C1–C2. • Motion testing: Segmental rotation restriction (hypomobility) with soft end-feel. • Muscle testing: The suboccipital muscles are shortened. • Autonomic symptoms: Nonsystematic vertigo, which may be exacerbated upon palpatory pressure (a). • The patient is seated. • With the upper cervical spine maximally flexed, the incriminated C1–C2 spinal segment is guided by the physician to its pathologic motion barrier (primarily a rotatory restriction). • The spinal segments distal to the C1–C2 spinal segment are fixated through the physician’s stabilizing hand by carefully introducing slight side-bending in the direction opposite to that of induced rotation. • The cervical spine is guided to its anatomic position or to the present neutral position (e. g., resting). • The other hand, the “treatment hand,” cradles the patient’s chin. • During inhalation, the patient is requested to perform an isometric contraction away from the pathologic motion barrier (b, d). At the same time, the patient is requested to look in the direction opposite that of the motion restriction. • During the postisometric relaxation phase, the patient is requested to look in the same direction as the pathologic barrier (direction of intended mobility gain = direction of intended improvement). • The physician then guides the head following the newly gained rotation motion, beyond the particular pathologic barrier. It is important not to release the stabilizing hold on the neighboring spinal segments as it is important to maintain their fixated/engaged position (c, e). • This technique is very well suited for the elderly patient. If the pain becomes prominent during the isometric contraction, the NMT 3 technique may be an acceptable alternative. • If there is patient-reported pain during the passive rotation beyond the initial motion barrier, it is advised that treatment be terminated immediately. • Pain: Acute or chronic; localized to the neck region; may be radiating to the occiput and the temporal region, as well as the area between the shoulder blades (a). • Irritation zone: C1–C2. • Motion testing: Segmental rotation restriction (hypomobility) with soft end-feel. • Muscle testing: The suboccipital muscles are shortened. • Autonomic symptoms: Nonsystematic vertigo, which may be exacerbated upon palpatory pressure (a). • The patient is seated. • With the upper cervical spine maximally flexed the incriminated C1–C2 spinal segment is guided by the physician to its pathologic motion barrier. • The spinal segments distal to the C1–C2 spinal segment are fixated through the physician’s stabilizing hand by carefully introducing sufficient, albeit slight, side-bending in the direction opposite of that of induced rotation. • The cervical spine is guided to its anatomic position or to the present neutral (resting) position. • The other hand, the “treatment hand,” cradles the patient’s chin. • During inhalation, the patient is requested to perform an isometric contraction toward the pathologic motion barrier (b, d). At the same time, the patient is requested to look in the direction opposite that of the motion restriction. • During the postisometric relaxation phase, the patient is requested to look in the same direction as the pathologic barrier (direction of intended mobility gain = direction of intended improvement). • The physician then follows the newly gained rotation (beyond the pathologic barrier) while guiding the head passively in a lateral direction. It is important not to release the stabilizing hold on the neighboring spinal segments so as to maintain their fixated/engaged position (c, e). • Pain: Acute or chronic; localized to posterior neck region; pain may also be reported to radiate toward the jaw, the region of the hyoid bone, and the anterior neck region (a). • Irritation zone: C2–C3. • Motion testing: Segmental rotation restriction (hypomobility) while C0–C1 is maximally flexed (maximal inclination position); soft end-feel. • Muscle testing: The hyoid muscles are shortened (a). • The patient is seated. • With the upper cervical spine maximally flexed, the incriminated C2–C3 spinal segment is engaged at its pathologic motion barrier by the physician. • The spinal segments distal to the C2–C3 spinal segment are fixated through the physician’s stabilizing hand by introducing some slight side-bending in the direction opposite of that of induced rotation. • The other hand, the “treatment hand,” cradles the patient’s chin very carefully. • During inhalation, the patient is requested to perform an isometric contraction away from the pathologic motion barrier (b, d). At the same time, the patient is requested to look in the direction opposite that of the motion restriction. • During the postisometric relaxation phase, the patient is requested to look in the same direction as the pathologic barrier (direction of intended mobility gain = direction of intended improvement). • The physician then passively follows the newly gained rotation motion (c, e). This technique is very well suited for the elderly patient. If pain or dizziness is reported during the isometric contraction, the NMT 3 technique may be an acceptable alternative. However, if the NMT 3 technique appears to cause similar symptomatology as well, then treatment should be halted altogether at that point. • Pain: Acute or chronic; localized to posterior neck region; the patient may also report pain in the jaw, in the region of the hyoid bone, and generally in the anterior neck region (a). • Motion testing: Segmental rotation restriction (hypomobility) while C0–C1 is maximally flexed (maximal inclination position); soft end-feel. • Muscle testing: The hyoid muscles are shortened (a). • The patient is seated. • With the upper cervical spine maximally flexed, the incriminated C2–C3 spinal segment is guided by the physician to its pathologic motion barrier. • The spinal segments distal to the C2–C3 spinal segment are fixated through the physician’s stabilizing hand by introducing some slight side-bending in the direction opposite of that of induced rotation. • The other hand, the “treatment hand,” cradles the patient’s chin very carefully. • During inhalation, the patient is requested to perform an isometric contraction in direction of the pathologic motion barrier (b, d). At the same time, the patient is requested to look in the same direction (c). • During exhalation, the patient is requested to continue to look in the same direction as the pathologic barrier (c, d) (direction of intended mobility gain = direction of intended improvement) while the head is being guided by the physician following the newly gained rotation motion. This technique is very well suited for the elderly patient. If pain or dizziness is reported during the isometric contraction (inhalation) or during the stretching portion of this maneuver (exhalation) the treatment should be halted altogether. • Pain: Acute in the neck region; pain may be reported as particularly severe upon initiation of movement of the head or neck (a). • Zone of irritation: C0–C1, C1–C2, C2–C3, exacerbated by palpatory pressure. • Motion testing: Painful segmental flexion and/or rotation restriction (segmental hypomobility); hard reflexogenic end-feel. • Muscle testing: The suboccipital muscles are shortened (a). • Patient is seated. • With elbows resting on the patient’s shoulders, the physician places both hands flat over the side of the patient’s head. • The spinal segments C0 to C3 are guided to their respective present neutral (resting) position (b). • Passive traction is introduced. • The timing is such that the traction component is introduced at the onset of a deep expiratory effort. • While the patient is instructed to continue deep inspiratory and expiratory efforts, the traction force is slowly and progressively increased (c). • After a few respiratory cycles, the traction force is slowly and carefully reduced. Note: It is important that the patient avoid overly ambitious inspiratory and expiratory excursions. • With the proper diagnosis and the correct application of this treatment procedure, the patient should notice a clear reduction of pain both during and after the treatment. • This traction procedure, when performed correctly, poses relatively little risk to the patient. • Pain: Acute, localized, or projecting toward the occiput (a). • Zone of irritation: C0–C1, C1–C2, C2–C3. • Motion testing: Regional flexion and rotation restriction (hypomobility) in the upper cervical spine with hard end-feel. • Muscle testing: Suboccipital muscles are shortened (a). • The patient is supine. • The patient’s head rests comfortably on the thighs of the physician, who is seated behind the patient. • With thumb and index finger of one hand, the patient’s occiput is held stationary by the physician while with the other hand cradles the patient’s chin. • Flexion motion (inclination) is introduced passively to the segments C0 to C2 (b). • Axial traction is introduced along the body’s longitudinal axis (c). • From this position, and with the patient adequately relaxed, a superiorly directed impulse (thrust) can be introduced in addition to the longitudinal tractional stretch. • Traction forces are specifically directed to the upper cervical spine between C0 and C3, naturally having some effect on the lower cervical spine as well. • A particularly useful technique for anxious patients and/or those presenting with acute neck pain. • With associated torticollis the exact present neutral position must be engaged very carefully. It is also essential not to introduce extension components to the upper cervical spine. • Especially in acute injury, or with known/suspected pathology (e. g., chronic polyarthritis/rheumatoid arthritis) pain or autonomic symptoms reported during the positioning or the maneuver should alert the operator to a potential need for further work-up. • In the presence of pain, autonomic symptoms/signs, or abnormal motion, the maneuver may need to be halted. • Pain: Localized; radiating toward the occiput and/or to the area of the cervicothoracic junction (a). • Zone of irritation: C0–C1, C1–C2, C2–C3. • Motion testing: Segmental motion restriction of flexion, extension, and rotation (inclination, reclination, rotation) with hard or soft end-feel. • The physician stands behind the seated patient and places his thumbs over the arch of the atlas, thereby creating a fulcrum (b). • With his other arm the physician then reaches around the patient’s chin and head, aligning the patient’s nose, chin, and elbow all in one plane (c). • By rotating his trunk (up to about 30% of the total range of motion), the physician guides the patient’s cervical spine passively to the pathologic barrier. Axial traction is carefully introduced. • A superiorly directed impulse is effected through the physician’s arm that cradles the patient’s chin and head. • Attention should be paid that no extension component whatsoever is introduced to the cervical spine with this maneuver (d). Since passive maximal rotation in the craniocervical junction may adversely affect the vertebral artery, one must pay particular attention to the following: • The patient should be as relaxed as possible. • The stabilizing (fixation) forces should be introduced very gently and carefully. • Pain: Acute; usually well localized and/or radiating toward the occipital area (a). • Zone of irritation: C0–C1, C1–C2, C2–C3. • Motion testing: Regional flexion and rotation motion restriction (hypomobility) with hard end-feel. • The physician, standing behind the patient, places one hand flat on either side of the patient’s head. • He carefully rests his forearms on the patient’s shoulders (b). • Passive inclination (flexion) is introduced to C0 to C2. • Traction along the body’s axis is introduced (c). • With the patient adequately relaxed, a superiorly directed impulse (thrust) can be carefully introduced. See also Mobilization with Impulse: Traction while the patient is supine (page 370). • Pain: Usually localized to the C0–C2 region, but may also radiate toward the occipital area (a). • Zone of irritation: C0–C1, C1–C2. • Motion testing: Segmental extension motion restriction (hypomobility) with hard end-feel. • Patient is supine. • The physician places the proximal phalanx of the index finger over the patient’s mastoid and occiput on the restricted side. • With the other hand he cradles the entire chin carefully in such a manner that the forearm overlies the patient’s temporal region on the side opposite of the restricted motion. • Some small degree of cervical spine flexion is carefully introduced (b). • Traction in a superior direction along the body’s axis is carefully introduced. • When the patient is relaxed, a superiorly directed impulse is introduced following the sagittal angle of the facet joint’s inclination (c). • Pain: Suboccipital area; occasionally the pain may radiate toward the occiput and/or the cervicothoracic junction (a). • Zone of irritation: C1–C2, C2–C3. • Motion testing: Regional/segmental rotation restriction (hypomobility) with hard end-feel. • Patient is supine. The patient’s head rests on the thighs of the physician, who is seated behind the patient. • The physician places the proximal phalanx of the index finger of the mobilizing hand over the transverse process and/or the posterior arch of the atlas or the axis on the restricted side. • With his other hand the physician fixates the patient’s opposite occiput (stabilization) (b). • The C1–C2 or C2–C3 segment is engaged at its pathologic motion barrier by introducing passive rotation, inclination (flexion) and side-bending toward the restricted side and toward the irritation zone. • A rotatory impulse force is introduced by directing the impulse vector towards the transverse process of the atlas (c). • Pain: Chronic; radiating toward the occiput and between the shoulder blades (a). • Irritation zone: C0–C1, C1–C2, C2–C3. • Motion testing: Inclination (flexion) restriction with soft end-feel. • Muscle testing: Shortening of the rectus capitis, obliquus capitis, and the semispinalis capitis muscles. Quite frequently, the descending portion of the trapezius and levator scapulae muscles are shortened as well, while the shoulder fixator muscles are often weak (a). • The patient is supine. • The patient’s shoulders rest on the examination table. • The physician carefully fixates with two fingers the articular pillars and spinous process of C3. • The head is embraced in such a manner that the patient’s forehead rests against the physician’s upper chest (at the level of the pectoralis muscle). • The hand is placed broadly over the occiput (b). • The spinal segments C0 to C3 are engaged at their respective pathologic barrier (b). • The patient is requested to isometrically extend the upper cervical spine during the inhalation cycle. The patient is requested to simultaneously direct his gaze in an upward direction (c). • During the exhalation phase, the spine is passively flexed by the physician’s hand and chest-shoulder, while the patient is further requested to look downward (d). • The patient is requested to isometrically contract against the physician’s resistance and in the same direction as the incriminated motion restriction. • The physician then engages the incriminated spinal segment(s) is at the new motion barrier. • It is important that the patient’s respiratory efforts are well synchronized with the isometric contraction and relaxation efforts. • This technique should not be used when there is a finding of hard end-feel coupled with inclination (flexion) restriction. • Pain: Chronic; the neck region; pain may also be reported as radiating to the shoulders and/or upper arms, the occipital region, and between the shoulder blades (a). • Irritation zone: C2–C3, C3–C4, C4–C5, C5–C6, C6–C7. • Motion testing: Segmental or regional rotation and/or side-bending restriction (hypomobility); hard end-feel. • Muscle testing: Shortening of the descending portion of the trapezius and levator scapulae muscles; the shoulder fixator muscles may be weak (a). • The patient is seated. • The cervical spine is guided to its anatomic neutral position or the present neutral position. • The inferior vertebral partner of the incriminated/restricted spinal segment is fixated by the physician placing the thumb and index finger of one hand over the articular pillars (viselike hand position) (b). • The restricted spinal segment is engaged at its pathologic motion barrier. • Passive mobilization is introduced by the physician’s small finger exerting a rotatory motion force at the articular pillar of the superior partner of the restricted spinal segment. • This rotatory force is also transmitted to the cervical spine above the incriminated spinal segment. • The other hand, the mobilizing hand, simultaneously introduces slight traction (c). Note: The path gained with each mobilization step is rather small. • This technique may also be used, albeit very carefully, for cervical radicular syndromes. Then, however, it is necessary to emphasize (increase) the superiorly directed traction component and only as long as the reported radicular pain does not increase in intensity. • If the patient reports that the pain is getting worse during the procedure, the following possible causes should be excluded: – The technique was performed with excessive force (i. e., poor technique). – Untoward pressure was been applied to the irritation zone. • Pain: Diffuse in the neck region; occasionally the pain may radiate in a pseudoradicular fashion to the arms and the region between the scapulae (a). • Irritation zone: C2–C3, C3–C4, C4–C5, C5–C6, C6–C7. • Motion testing: Segmental or regional rotation restriction (hypomobility) with hard end-feel. • The patient is supine. • The physician places the proximal phalanx of his index finger over the transverse process of the inferior partner of the incriminated restricted segment. • With his other hand, the physician cradles the patient’s occiput. • The restricted spinal segment is passively rotated until it is engaged at its pathologic barrier (b). • Slight traction is introduced to the entire cervical spine (b). • The direction of the impulse is along the path of rotation, (c). • The mobilizing force is also transmitted to the inferior cervical spinal segments, with the intensity diminishing from superior to inferior. • This technique can potentially compromise the vertebral artery; thus careful and exact execution of treatment is imperative. • Pain: Localized; occasional pseudoradicular radiation to the upper limb and/or the area between the scapulae (a). • Irritation zone: C1–C2, C2–C3, C3–C4, C4–C5, C5–C6 • Motion testing: Segmental or regional rotation and side-bending restriction (hypomobility) with hard end-feel. • The patient is seated. • The physician stands on one side of the patient. • With one hand, the physician fixates/stabilizes the patient’s head at the temporal region (b). • The middle and index fingers of the other hand are placed over the articular pillar of the vertebra below the incriminated restricted segment (c, d). • Passive side-bending and rotation are introduced, engaging the spinal segment at its pathologic barrier. • Slight traction is simultaneously applied (c). • The impulse is introduced through the articular pillar of the vertebra below the restricted segment. The thrusting force is directed anterosuperiorly following the planes of the facets (e). Caveat: No impulse (thrust) forces should be allowed to be introduced by the fixating hand. This is an excellent technique for anxious patients who have difficulty relaxing. • Pain: Localized; occasionally radiating into the arms or the region between the scapulae (a). • Irritation zone: C2–C3, C3–C4, C4–C5, C5–C6. • Motion testing: Segmental rotation and side-bending restriction (hypomobility) with hard end-feel. • The patient is seated. • The physician places his second metacarpal bone and the thumb of one hand over the articular pillar of the vertebra below that of the incriminated/restricted spinal segment. • The other arm embraces the patient’s head at the temporooccipital region, while the hypothenar eminence and the small finger are placed over the vertebra above that is incriminated/restricted (b). • The physician introduces sufficient rotation to the head and upper cervical spine until the pathologic barrier of the restricted spinal segment is engaged. • A rotatory impulse with a slightly superior component (approximately 15°) is directed toward the vertebra that is directly inferior to the restricted spinal segment (c). • The impulse (thrusting force) is introduced during the expiratory effort. • This is quite an effective technique, especially for dysfunctions localized to the mid-cervical spine. • The patient should be as relaxed as possible. • Pain: Localized; occasionally radiating into the arms or the region between the shoulder blades (a). • Irritation zone: C2–C3, C3–C4, C4–C5, C5–C6, C6–C7. • Motion testing: Segmental rotation restriction (hypomobility) with hard end-feel. • The patient is seated.

Structural Examination and Functional Treatment of the Cervical Spine

Palpation of Bony Landmarks Cervical Spine (Fig. 15.1)

Occiput (Fig. 15.1)

External Occipital Protuberance

Superior Nuchal Line

Inferior Nuchal Line

Mastoid Process

Upper Cervical Spine (C0–C1, C1–C2) (Fig. 15.1)

Transverse Process of the Atlas

Posterior Arch of the Atlas

Spinous Process of C2

Lower Cervical Spine (C6 and C7) (Fig. 15.1)

Irritation Zones (IZ) Associated with the Cervical Spine

Occipitoatlantal Articulation (C0–C1)

Atlantoaxial Joint (C0–C1) through C5–C6 Articulation

C6–C7 Articulation

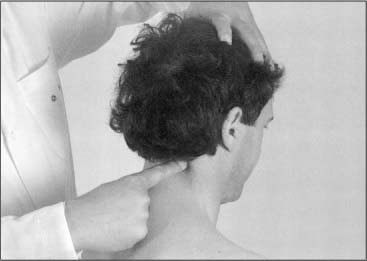

Provocation Maneuvers

Examination Procedure

Structural Examination of the Cervical Spine

C0 through C7

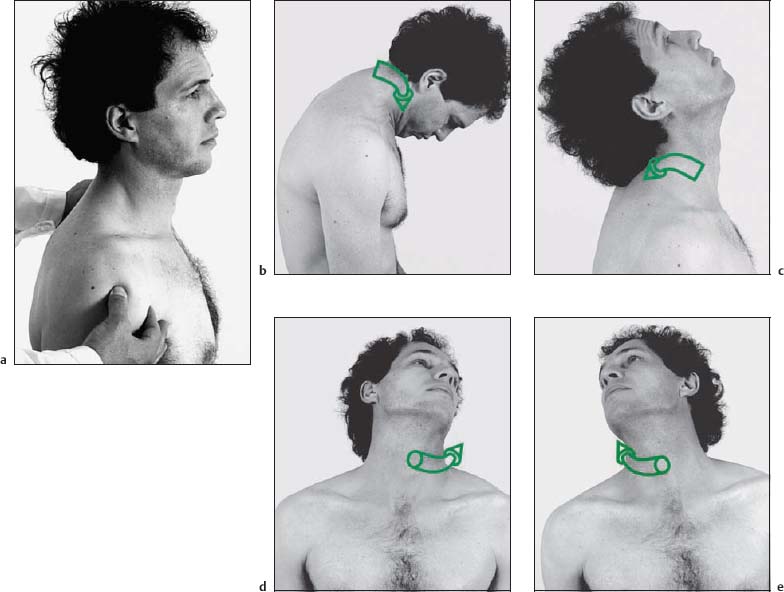

Evaluation: Active Motion Testing of Flexion, Extension, Rotation, and Side-Bending (Figs. I15.1a–e)

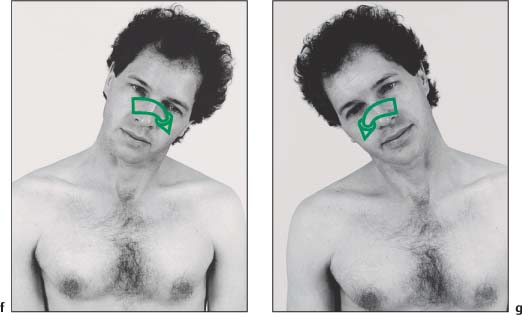

Examination Procedure

C0 through C7

Evaluation: Active Motion Testing of Flexion, Extension, Rotation, and Side-Bending (Figs. I15.1f, g)

Positive Findings

C0 through C7

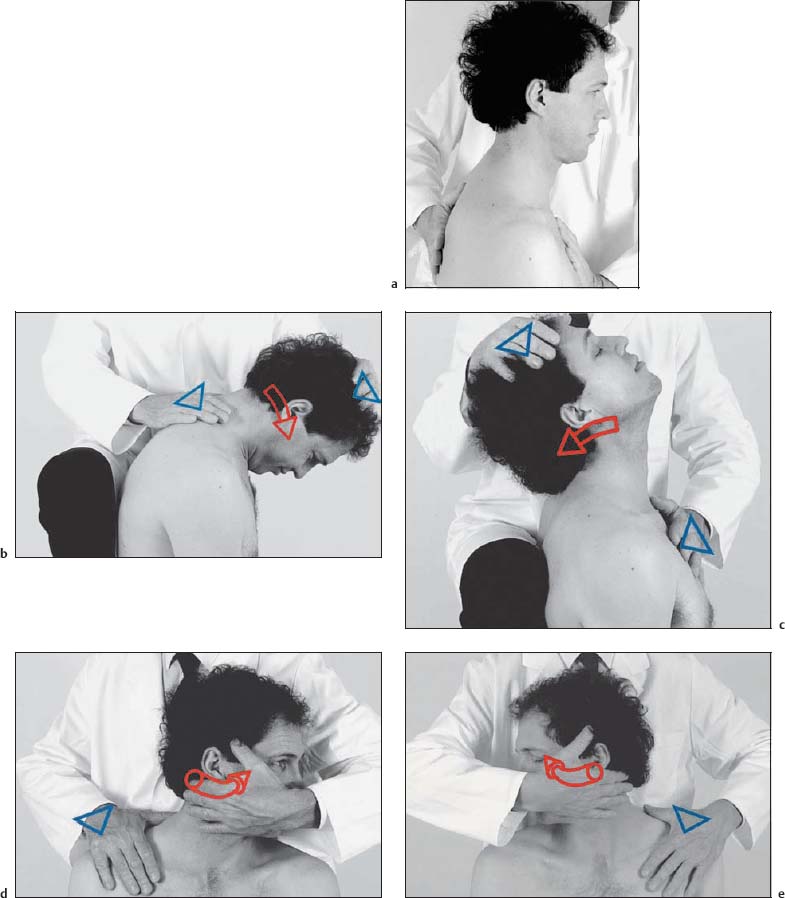

Evaluation: Passive Motion Testing of Flexion, Extension, Rotation, and Side-Bending (Figs. I15.2a–e)

Examination Procedure

C0 through C7

Evaluation: Passive Motion Testing of Flexion, Extension, Rotation, and Side-Bending (Figs. I15.2f, g)

Positive Findings

C3 through C7

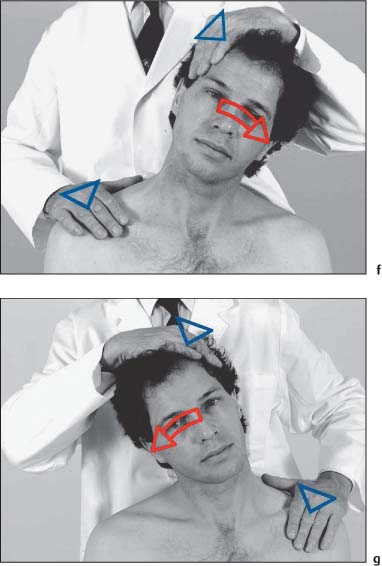

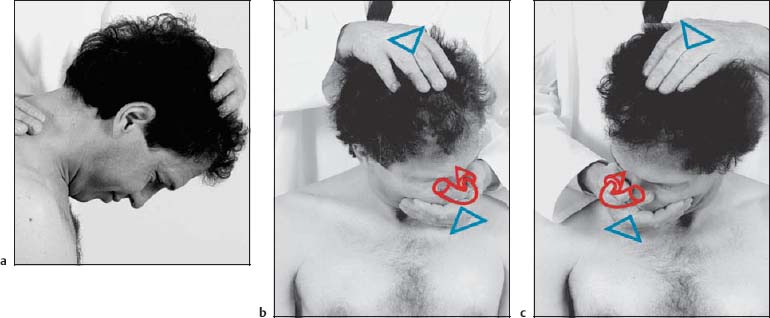

Evaluation: Rotation in Extension (Figs. I15.3a–c)

Examination Procedure

Positive Findings

C0 through C7

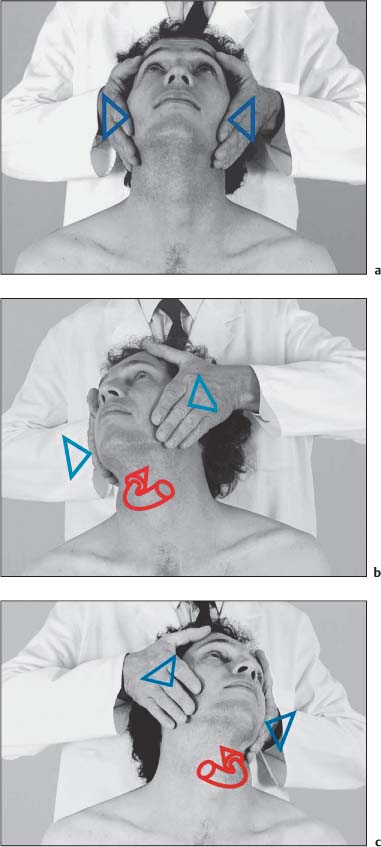

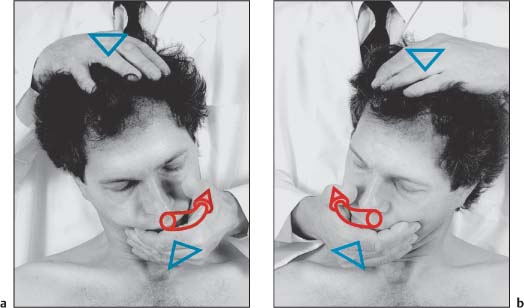

Evaluation: Provocation Position and Motion Testing of the Vertebral Artery by Rotation and Reclination (Figs. I15.4a–c)

Examination Procedure

Positive Findings

C0 through C3

Evaluation: Active Motion Testing for Inclination and Reclination (Figs. I15.5a, b)

Examination Procedure

Positive Findings

C0 through C3

Evaluation: Passive Motion Testing for Inclination and Reclination (Figs. I15.6a, b)

Positive Findings

C0–C1

Evaluation: Passive Motion Testing of Axial Rotation and Evaluation of Joint Play (Figs. I15.7a–d)

Examination Procedure

Positive Findings

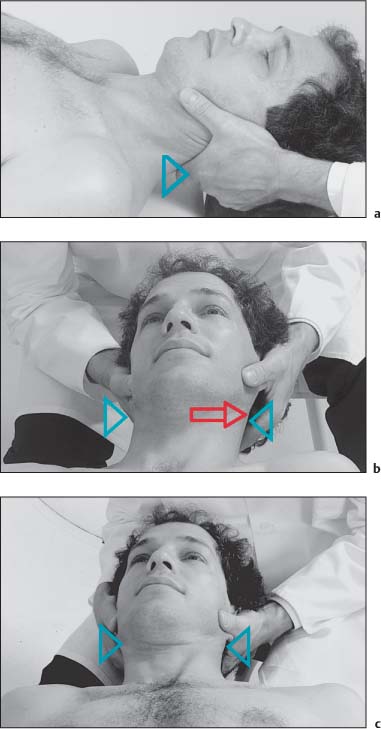

C0 through C3

Evaluation: Side-Bending at the C0–C1 and C1–C2 Segments (Figs. I15.8a, b)

Examination Procedure

Positive Findings

C1–C2

Evaluation: Active Motion Testing of Axial Rotation (Figs. I15.9a–c)

Examination Procedure

Positive Findings

C1–C2

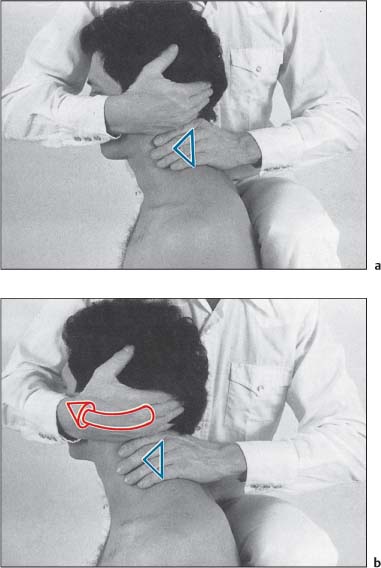

Evaluation: Passive Motion Testing of Axial Rotation (Figs. I15.10a–c)

Examination Procedure

Positive Findings

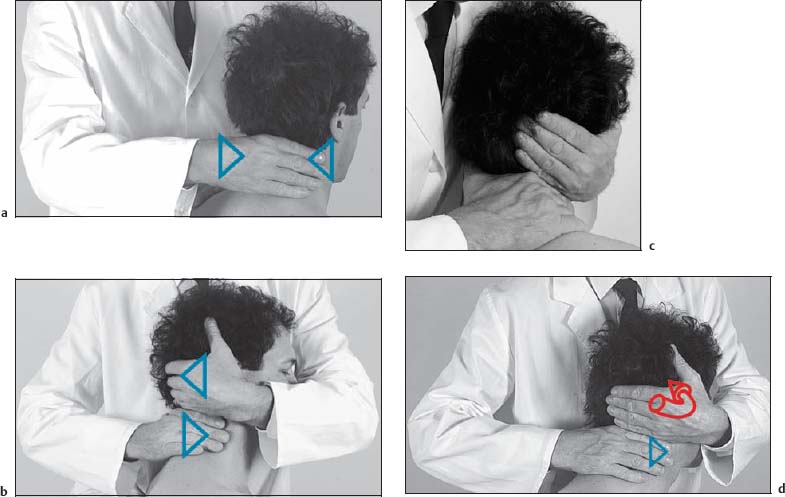

C1–C2

Evaluation: Passive Motion Testing of Axial Rotation at C1–C2 and Evaluation of Joint Play (Figs. I15.11a, b)

Examination Procedure

Positive Findings

C1–C2

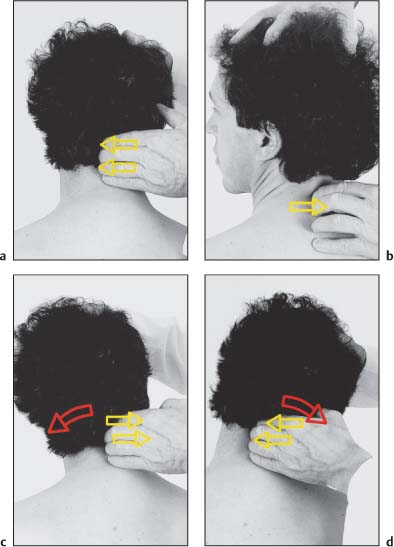

Evaluation: Forced Rotation of the Axis with Side-Bending, Axis Rotation (Figs. I15.12a–d)

Examination Procedure

Positive Findings

C2–C3

Evaluation: Passive Rotation Testing (Figs. I15.13a, b)

Examination Procedure

Positive Findings

C0 through C3

Evaluation: Translatory Gliding at C0 through C3 (Figs. I15.14a–c)

Examination Procedure

Positive Findings

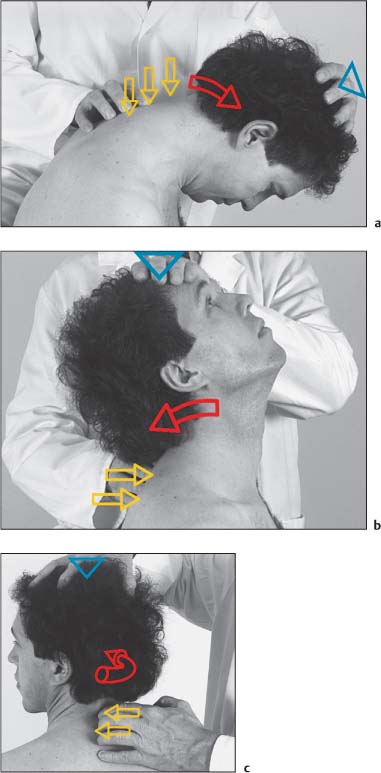

C4 through C7

Evaluation: Passive Flexion, Extension, Side-Bending, and Rotation Motion (Figs. I15.15a–f)

Examination Procedure

Positive Findings

C3 through C7

Evaluation: Passive Flexion, Extension, Side-Bending, and Rotation Motion (Figs. I15.16a–d)

Examination Procedure

Positive Findings

C3 through C6

Evaluation: Translatory Gliding (Figs. I15.17a–c)

Examination Procedure

Positive Findings

Functional Treatment of the Cervical Spine

C0–C1

Mobilization without Impulse: Inclination (Flexion) and/or Reclination (Extension) Restriction (Figs. I15.18a–d)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Treatment Procedure

Comments

C1–C2

Mobilization without Impulse: Rotation Restriction (Figs. I15.19a–d)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Treatment Procedure

Comments

C0–C1

NMT1: Inclination (Flexion) and/or Reclination (Extension) Restriction (Figs. I15.20a–d)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Treatment Procedure

Comments

C0–C1

Self-Mobilization: Inclination (Flexion) and/or Reclination (Extension) Restriction (Figs. I15.21a–d)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Treatment Procedure

C1–C2

NMT1: Rotation Restriction (Figs. I15.22a–c)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Treatment Procedure

Comments

C1–C2

Self-Mobilization: Rotation Restriction (Figs. I15.23a–c)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Treatment Procedure

Comments

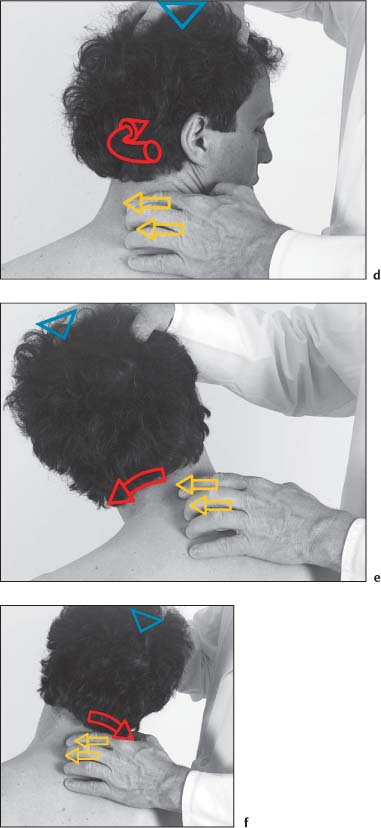

C1–C2

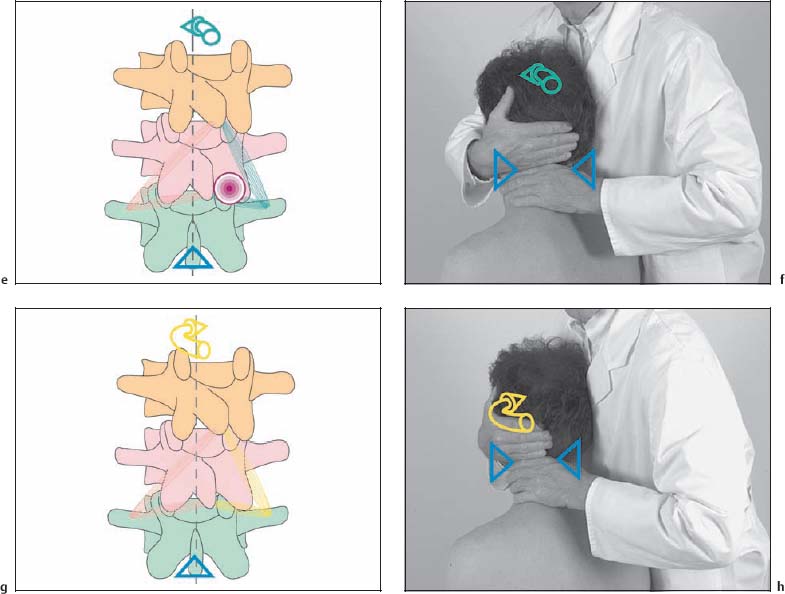

NMT 2: Rotation Restriction (Neutral Position) (Figs. I15.24a–h)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Treatment Procedure

Comments

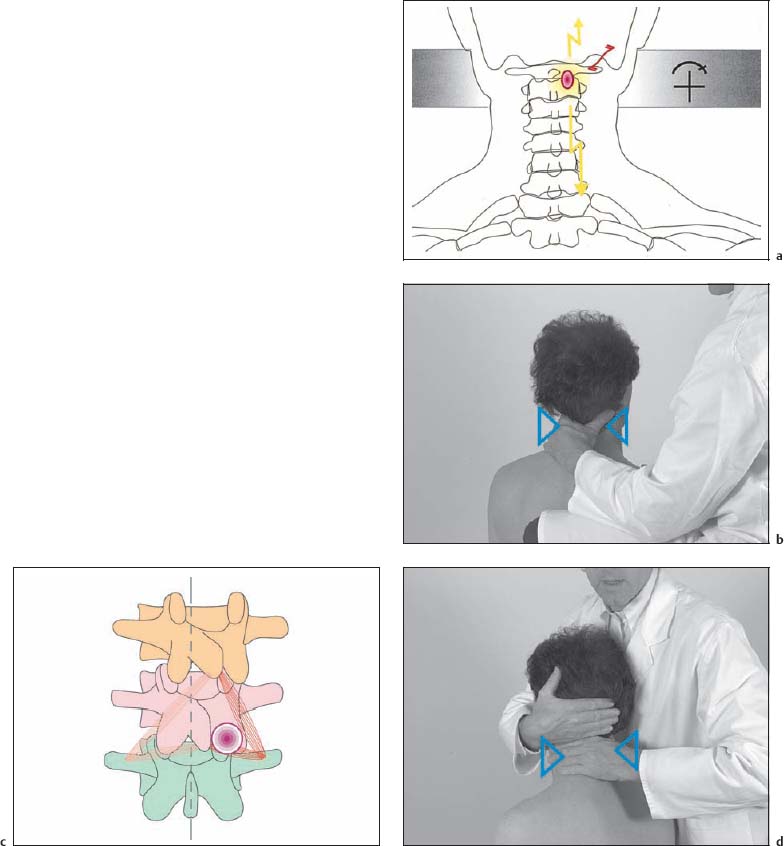

C1–C2

NMT 3: Rotation Restriction (Neutral Position) (Figs. I15.25a–d)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Treatment Procedure

Comments

C1–C2

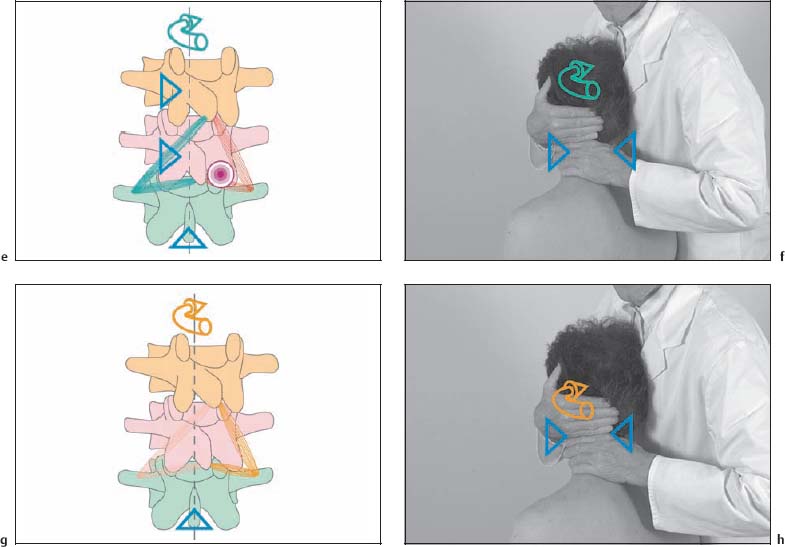

NMT 2: Rotation Restriction (with Upper Cervical Spine Fully Flexed) (Figs. I15.26a–e)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Treatment Procedure

Comments

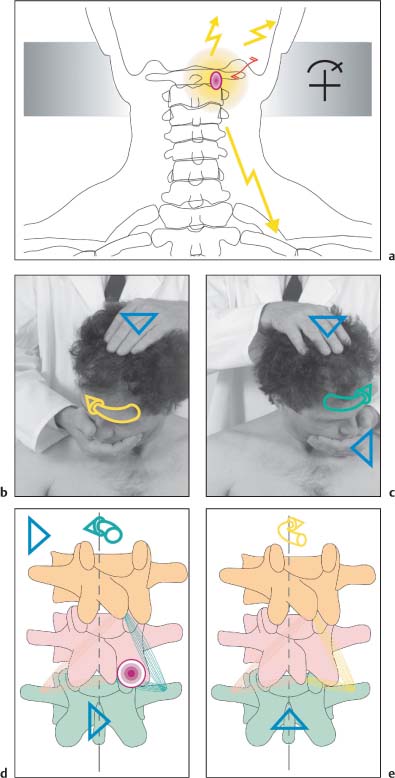

C1–C2

NMT 3: Rotation Restriction (with Upper Cervical Spine Fully Flexed) (Figs. I15.27a–e)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Treatment Procedure

C2–C3

NMT 2: Rotation Restriction (Figs. I15.28a–e)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Treatment Procedure

Comments

C2–C3

NMT 3: Rotation Restriction (Figs. I15.29a–e)

Indications

Patient Positioning

Treatment Procedure

Comments

C0 through C3

Mobilization without Impulse: Axial Traction (Figs. I15.30a–c)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Treatment Procedure

Comments

C0 through C3

Mobilization with and without Impulse: Cervical Traction (Figs. I15.31a–c)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Treatment Procedure

Comments

C0 through C3

Mobilization with Impulse (Thrust): Traction (Figs. I15.32a–d)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Treatment Procedure

Comments

C0 through C3

Mobilization with Impulse (Thrust): Axial (Longitudinal) Traction (Figs. I15.33a–c)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Treatment Procedure

Comments

C0 through C2

Mobilization with Impulse (Thrust): Traction (Figs. I15.34a–c)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Treatment Procedure

C1 through C3

Mobilization with Impulse (Thrust): Rotation Restriction (Figs. I15.35a–c)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Treatment Procedure

C0 through C3

NMT 2 and NMT 3: Inclination (Flexion) Restriction (Figs. I15.36a–d)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Treatment Procedure

NMT 2

NMT 3

Comments

C2 through C7

Mobilization without Impulse: Rotation Restriction (Figs. I15.37a–c)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Treatment Procedure

Comments

C2 through C7

Mobilization with Impulse (Thrust): Rotation Restriction (Figs. I15.38a–c)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Treatment Procedure

Comments

C1 through C6

Mobilization with Impulse (Thrust): Rotation Restriction (Figs. I15.39a–e)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Treatment Procedure

Comments

C2 through C6

Mobilization with Impulse (Thrust): Rotation Restriction (Figs. I15.40a–c)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Treatment Procedure

Comments

C2 through C7

Mobilization with Impulse (Thrust): Rotation Restriction (Figs. I15.41a–c)

Indications

Patient Positioning and Set-up

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree