Fig. 7.1

An 18-year-old collegiate track and field athlete with a left sacral stress fracture. (a, b) The anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the lumbosacral spine do not show any osseous abnormalities indicative of a sacral stress fracture. (c, d) Coronal and axial T2 MRI, respectively, demonstrate a linear fracture line within the left sacral ala involving the left first and second sacral neural foramina with associated adjacent marrow edema compatible with sacral stress fracture

Pubic Rami Stress Fractures

Wachsmuth first described stress fractures of the pubic ramus in three male military recruits in 1937 [27]. Although these are rare injuries with few described in the literature, they have been found to be common in female military personnel and athletes [28–31]. In the female military population, it has been hypothesized that an increased force is placed on the pubic rami in order for these recruits to maintain the same stride length as their male colleagues [32]. Another explanation is a greater concentration of cancellous bone in this pelvic region in the female gender [33].

Pubic ramus stress fractures usually occur at the medial portion of the inferior pubic ramus adjacent to the pubic symphysis. This injury is caused by excessive contraction of the adductor magnus muscle at its origin between the ischial tuberosity and the inferior pubic ramus [29]. The adductor magnus pulls the lateral aspect of the pubic ramus when the hip is extended thus initiating the development of these fractures [30]. These injuries have been postulated to occur more frequently in females because females have a greater reliance on hip external rotation in their gait cycle [34, 35] (Fig. 7.2).

Fig. 7.2

The origin of the adductor magnus and hamstring muscles, shown with the most common site of pelvic stress fracture

Presentation and Physical Examination

Typically, patients present with groin pain that is exacerbated by activity. On physical examination, the athlete may have an antalgic gait as well as demonstrate exquisite tenderness to palpation at the pubic ramus. The patient will display full range of motion of the hip; however, there may be discomfort with hip external rotation and pain with resisted adduction. Additionally, the patient will demonstrate a positive “standing test,” the inability to stand unsupported on the affected lower extremity [30].

Diagnostic Imaging

Diagnostic evaluation begins with an anteroposterior pelvis radiograph that can show a non-displaced fracture at the inferior pubic ramus near the pubic symphysis. Unfortunately, in the early stages of this injury, plain radiographs will likely not pick up this stress fracture; therefore, bone scintigraphy can be considered since it is a more sensitive indicator of early stress fractures when compared to plain radiographs [36]. Additionally, MRI has been found to provide more diagnostic information such as the presence of fracture lines and bone edema.

Iliac Wing Stress Fractures

Iliac wing stress fractures are extremely rare, consisting of 4 % of all pelvic stress fractures [37, 38]. There are only a total of four case reports in the literature of these injuries: two case reports of iliac wing injuries that extend into the SI joint, and two other reports that do not involve the SI joint. Patients with this condition are usually long distance runners complaining of lateral-based hip pain without a history of trauma. The mechanism of injury is believed to be the result of osseous failure secondary to two opposing repetitive loads: cephalad traction from the musculature of the abdominal wall and a caudal force from the abductors inserting onto the iliac crest (Fig. 7.3a–f).

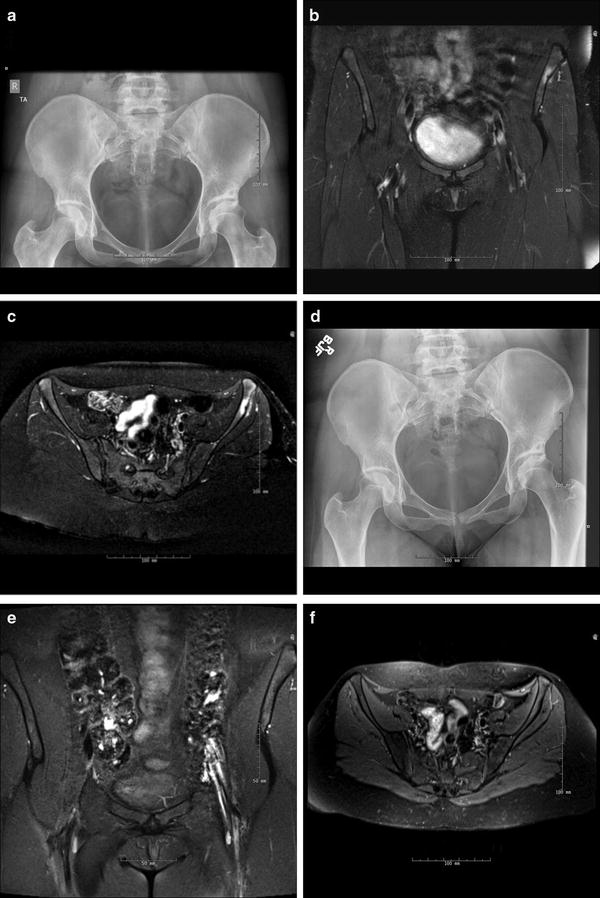

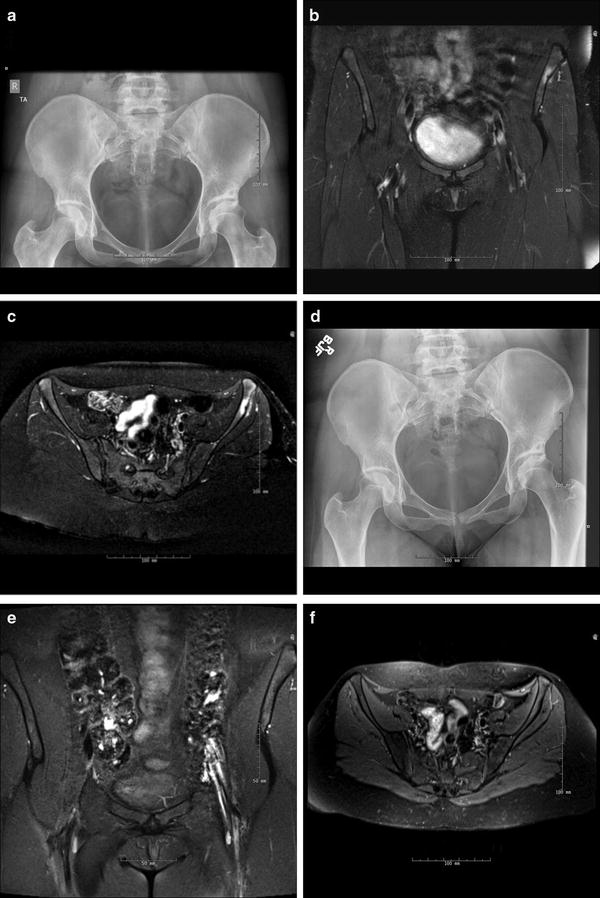

Fig. 7.3

A 20-year-old marathon runner with a left iliac wing stress fracture. (a) The anteroposterior (AP) pelvis radiograph shows some sclerosis on the left iliac brim with no obvious fracture line. Part (b) is a coronal T2 MRI image demonstrating a small area of ill-defined marrow edema involving the left iliac wing just inferior and posterior to the ASIS. Part (c) is an axial T2 MRI image demonstrating a small linear area of decreased signal along the lateral cortex with mild periosteal edema. Both findings are consistent with stress fracture. Part (d) is an AP pelvis radiograph 3 months after presentation after cessation of activity with no interval change; however, parts (e) and (f) are coronal and axial T2 MRI images demonstrating resolution of the bony edema

Apophyseal Avulsion Fractures

Apophyseal avulsion fractures are stress injures about the pelvis that are present in adolescent athletes and, occasionally, patients in their mid-20s [39]. These stress injuries are the result of indirect trauma caused by a forceful concentric or eccentric contraction of the muscle that is attached to the apophysis. This causes failure through the growth plate and is the result of the inherent weakness across the unfused apophysis of a skeletally immature athlete. In a more skeletally mature athlete with the same mechanism of injury, these injuries would result in a musculotendinous tear of the affected muscle (Fig. 7.4).

Fig. 7.4

The most commonly affected apophyses. Inset: The ASIS is the attachment site for the sartorius and some fibers of the tensor fascia lata. Avulsion of the ASIS occurs from a strong sudden pull of the sartorius with the hip in extension and the knee in flexion, most commonly in sprinters, hurdlers, and other running athletes

In this adolescent population, there are two types of epiphyses: pressure epiphyses and traction epiphyses. A pressure epiphysis is at the end of long bones and is subjected to the pressures across the joint. Meanwhile, a traction epiphysis is an apophyseal growth plate on which a major muscle or muscle group originates or inserts and is most commonly involved in these avulsion injuries (Table 7.1). Within the traction epiphysis, the epiphyseal plate is the weakest point because the tendon’s Sharpey’s fibers that attach to the growth plate are stronger than the junction of cells between the calcified and uncalcified epiphysis. As a result, osseous failure occurs within the zone of hypertrophy of the growth plate [40].

Table 7.1

Common sites of apophyseal avulsion fractures about the pelvis and their muscular attachments

Common site of avulsion in pelvis | Muscle attachment |

|---|---|

Anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS) | Direct head of the rectus femoris |

Anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) | Sartorius and tensor fascia lata |

Iliac crest | External and abdominal obliques |

Ischial tuberosity | Proximal hamstring |

Pubic symphysis | Hip adductors |

In a radiologic epidemiologic study, Rossi et al. studied more than 1,000 radiographs and found 203 pelvic apophyseal avulsion injuries [41]. In this series, the most common injuries were at the ischial tuberosity (54 %) followed by the anterior inferior iliac spine (22 %), the anterior superior iliac spine (19 %), the pubic symphysis (3 %), and the iliac crest (1 %). Soccer players were at greatest risk (74 injuries) followed by gymnasts (55 injuries) [37].

Presentation and Physical Examination

The affected athlete presents with an acute onset of pain that occurs during a sporting maneuver. Generally, there is swelling and localized tenderness to palpation about the site of injury with discomfort exacerbated by the use of the attached muscle. The affected extremity will maintain a position that places the least amount of tension on the involved muscle and the patient will guard against active contraction of this muscle.

Diagnostic Imaging

The clinical evaluation is usually diagnostic; however, plain radiographs are helpful to determine the degree of bony displacement and the size of the avulsed fragment. These injuries are usually evident on plain anteroposterior pelvic radiographs, but an additional oblique projection might be needed to appreciate the fracture (Figs. 7.5a, b and 7.6a, b). MRI can be useful to evaluate for avulsion fractures in children with ossification centers that have not ossified yet as well as to assess for apophysitis. Additionally, ultrasound can be considered as a cost-effective modality that has been found to be accurate in diagnosing these avulsion injuries [42].

Fig. 7.5

A 15-year-old football player with subacute avulsion of the right ischial tuberosity. (a, b) The anteroposterior (AP) and right frog-leg lateral radiographs demonstrating a healing ischial tuberosity avulsion fracture

Fig. 7.6

A 15-year-old basketball player with antecedent pain at the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) with an acute avulsion of the right ASIS that occurred while attempting to dunk the basketball. (a, b) The anteroposterior (AP) and right frog-leg lateral radiographs demonstrate the healing avulsion fracture

Management

The majority of the aforementioned pelvic stress fractures can be treated through nonsurgical means consisting of rest, activity modification, and then a gradual return to athletics. Additionally, any patient with a suspected pelvic stress fracture should undergo a metabolic evaluation consisting of blood and urine work as well as the intake of calcium and vitamin D. A three-phase program has been developed to get athletes back to sport with the presence of pain as the guiding factor in progression through the program [25, 43].

Stage 1 consists of avoiding painful activities. Some sacral fractures may require the athlete to be non-weightbearing with the assistance of crutches. Once pain with ambulation has been eliminated, these crutches can be discontinued. Stage 2 is then initiated once the patient has been pain-free with activities of daily living for 3–5 days. This second phase focuses on strength training and correcting any pelvic muscular imbalance through light-weight and nonimpact exercises. Additionally, sports-specific muscular rehabilitation is initiated at this time. Stage 3 allows the athlete to gradually return to play with progression to normal athletic load for the athlete’s specific sport. Overall, this process can range from 3 to 18 weeks [25]. It is important to note that premature return to sport prior to complete union can increase the risk of complications such as delayed union or nonunion.

Apophyseal avulsion fractures are also treated conservatively similar to the previously described program. These athletes generally return to athletics no earlier than 2 months after the initial injury [44]. Unlike the other pelvic stress fractures, apophyseal injuries can be amenable to surgical intervention with open reduction internal fixation in order to prevent disability in competitive athletes. Some advocate operative intervention if the avulsed fracture fragment is more than 2 cm in size; however, these indications and the optimal timing of surgery still remain debated [45].

The Role of Nutrition

In athletes with stress fractures, nutritional and hormonal imbalances are frequently prevalent. Any patient with a suspected pelvic stress fracture should undergo a metabolic evaluation consisting of blood and urine work as well as the dietary intake of calcium and vitamin D. These two minerals have been found to be integral components of nutrition required to achieve and maintain bone homeostasis. Calcium provides strength to the bone through a mineralized matrix and serves as the primary storage of calcium in the body. Vitamin D assists with the absorption of calcium from the digestive tract and renal systems and promotes bone growth and remodeling. Additionally, these minerals have been shown to improve bone density and prevent fractures at all ages. These injuries are most commonly seen in the female gender as this group of athletes experiences the loss of the bone-maintaining effects of estrogen. Additionally, these athletes have a reduction in calcium and vitamin D all of which place them at an increased risk of stress fractures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree