Abstract

Cardiovascular events and emotional disorders share a common epidemiology, thus suggesting fundamental pathways linking these different diseases. Growing evidence in the literature highlights the influence of psychological determinants in somatic diseases. A patient’s socio-economic aspects, personality traits, health behavior and even biological pathways may contribute to the course of cardiovascular disease. Cardiac events often occur suddenly and the episode can be traumatic for people not prepared for such an event. In this review of the literature, the authors tackle the question of psychobiological mechanisms of stress, in a pathophysiological approach to fundamental pathways linking the brain to the heart. Various psychological, biological and genetic arguments are presented in support of the hypothesis that various etiological mechanisms may be involved. The authors finally deal with biological and psychological strategies in a context of cardiovascular disease. Indeed, in this context, cardiac rehabilitation, with its global approach, seems to be a good time to diagnose emotional disorders like anxiety and depression, and to help people to cope with stressful events. In this field, cardiac rehabilitation seems to be a crucial step in order to improve patients’ outcomes, by helping them to understand the influence of psychobiological risk factors, and to build strategies in order to manage daily stress.

1

Introduction – epidemiological features

There is a substantial amount of evidence in the literature underlining the impact of psychological determinants on the onset of heart disease. Depression, a disease with a very high psychosocial burden, also has a detrimental effect in terms of cardiovascular disease. Indeed, people suffering from depression are as twice as likely as the general population to develop myocardial infarction and this cardiovascular comorbidity increases mortality in people with depression, even more than death by suicide . Although the precise nature of the links between depression and coronary heart disease (CHD) have not yet been clearly established, these links are being highlighted more and more frequently, first of all from an epidemiological point of view and then with regard to the etiological and clinical aspects in patients with this worrying comorbidity. Quite recently, Eichstaedt et al. showed in a US county a robust positive relationship between negative emotions (anger, hostility, boredom) expressed in twitter messages and cardiovascular deaths, thus strengthening the link between negative thinking and cardio-metabolic disorders . A few years ago, the Interheart study reported the impact of psychic disease on coronary artery disease and the importance of psychosocial stress (a notion that includes depression), which was put in third place in the league table of risk factors (with an odds ratio of 2.67) for developing cardiovascular disease , after the apolipoprotein B/apolipoprotein A1 ratio and smoking but in front of diabetes, arterial hypertension and abdominal obesity. Negative emotional states therefore appear to be strongly associated with cardiovascular events. Because of these psychological, behavioral and biological relationships between the brain and heart, it seems important to consider the reality of these deleterious links before including specific strategies in rehabilitation programs in order to reduce adverse consequences in patients with cardiovascular disease.

2

Methods

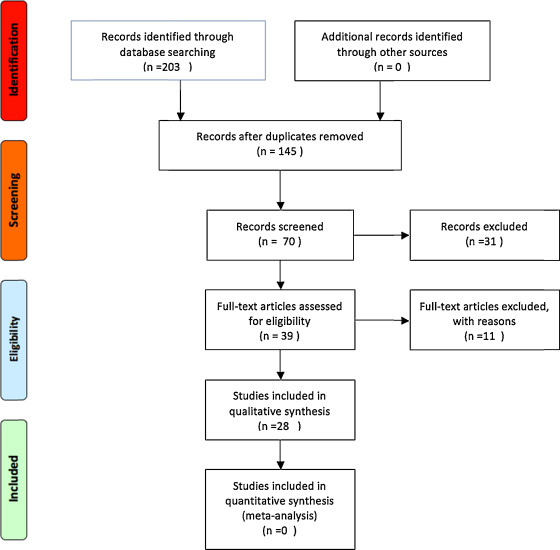

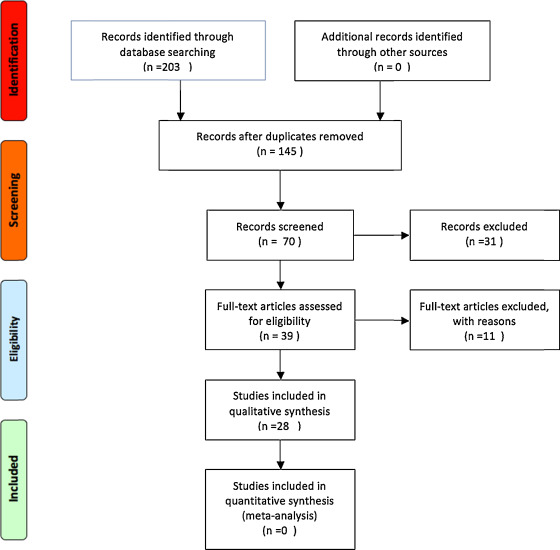

In this review, relevant studies from 2000 to 2016 were selected and analyzed ( Fig. 1 ). Medical subject heading (MeSH) terms “stress”, “anxiety”, “depression”, “personality”, “cardiovascular disease” and “rehabilitation” were used to perform key word searches of the PubMed database.

2

Methods

In this review, relevant studies from 2000 to 2016 were selected and analyzed ( Fig. 1 ). Medical subject heading (MeSH) terms “stress”, “anxiety”, “depression”, “personality”, “cardiovascular disease” and “rehabilitation” were used to perform key word searches of the PubMed database.

3

Results

Fig. 1 shows studies and results of the selection and screening process. In total, 201 papers were founded through PubMed database searches. After removing duplicates, 145 remained. Of these, 70 papers were reviewed and 31 were not related to research designs and were excluded. Thirty-nine studies remained and 11 articles were excluded because of methodological bias (e.g. inclusion/exclusion criteria, etc.). Then, 28 studies appeared to be suitable, in relation to stress, anxiety and depression in people with heart disease. Studies included showed the cardiovascular impact of either usual psychological stress or emotional disturbances like anxiety and depression. In addition, several studies illustrated the scientific rationale for anxiety/depression diagnosis in people with heart disease and the dramatical interest of stress management especially in cardiac rehabilitation.

3.1

The cardiovascular impact of stress in usual conditions

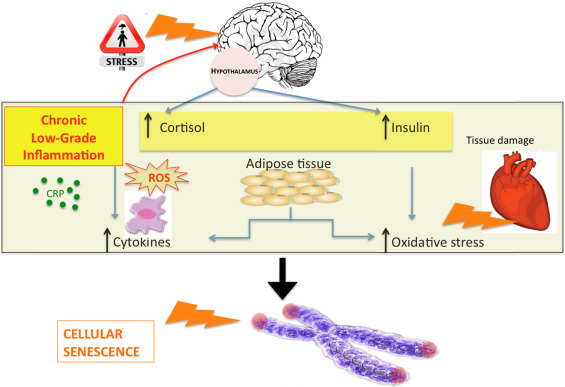

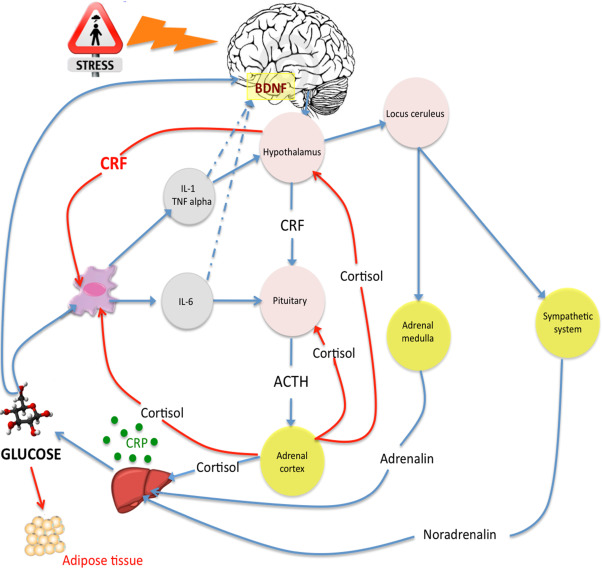

There is more and more evidence of the impact of psychological factors on the onset of somatic diseases in general and cardiovascular disease in particular. In the field of psychobiological theory, which tries to explain the link between the brain, cognition, emotion and body, stress theory is a credible way to model this psychosomatic enigma. The stress response appears to play a central role in the interface between the brain, feelings, behavior and biological effects. The old concept of stress by Hans Selye has moved forward, because of progress in medical sciences and psychology. Indeed, as Hans Selye used to say, stress is life, and the brain and body must constantly adapt in order to respond to various stimuli . The effect of multiple stimulations makes the body respond in biological, cognitive and emotional ways. The stress response involves the central activation of brain systems responsible for the analysis of the environment. This response is important and appears not to be deleterious, as it promotes a physiological balance in response to classic and normal environmental stressors. However, in the case of chronic and mainly psychosocial stressors, the allostatic system may be overwhelmed with hyperactivation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and the autonomic nervous system with dysregulation of blood pressure and cortisol levels . In addition, an immuno-inflammatory response occurs with the production of inflammatory cytokines . If this phenomenon lasts for a long time because of chronic adversity (work or social stress, for instance), the pathophysiological effects can lead to metabolic disturbances (glucose and lipid dysregulation), metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease ( Fig. 2 ). Then, psychological factors like perceived stress, coping style, personality traits, or social support might modulate the stress response.

3.1.1

Perceived stress

The reaction to stress is not an automatic process directly associated with the environment or stressors, but stress occurs in a transactional way between the environment and the subject . This is why perceived stress is a better approach to describe stress reactions. Perceived stress is the subjective evaluation of stressors, in a non-linear manner from the stressor to the stress response, depending on personal properties like gender and experience. What is important to note is that the same traumatic event may be experienced quite differently by two different people because of differences in perceived stress. Though the intensity of the perceived stress may be associated with biological and psychological consequences, other psychological dimensions, such as coping strategies or personality traits, are involved in the stress reaction.

3.1.2

Coping style

Coping is defined as all the cognitive and behavioral efforts made in order to manage internal or external stimuli potentially exceeding personal resources. The use of one or another coping strategy is determined by the stress event (type, severity, length, controllability, etc.) and by the subject’s profile (cognition, personality, personal history, etc.) . Two main coping strategies are described, a problem-focused coping style and an emotion-focused coping strategy. A problem-focused coping strategy is an active strategy that relies on using active ways to directly tackle the situation that caused the stress. Emotion-focused strategies aim to reduce and manage the intensity of the negative and distressing emotions that a stressful situation has caused rather than solving the problematic situation itself. Problem-focused strategies seem to be more effective in manageable situations like coronary heart disease where drug observance and balanced diet are required to improve the disease outcome. However, in situations of unsolvable situations (diseases with a bleak prognosis, for instance), emotion-focused strategies are useful to cope with the situation, by escaping from the dark reality, etc. In controllable diseases or in terms of diet or health behavior where active strategies may be required to avoid dangerous behavior, a problem-focused style is effective to solve problems and to reduce the effects of stress.

3.1.3

Personality traits

In the history of the concept of stress and psychosomatics, personality clusters used to be an important notion. Indeed, in early reports, the Type A personality, defined by the combination of several traits encompassing a sense of time urgency, high job involvement, strong drive, a need for achievement, ambition and competitiveness, was associated with coronary artery disease. However, subsequent studies have dismissed this link and focused on hostility as the “toxic” component . Indeed, cardiovascular mortality was found to be primarily due to cognitive hostility (i.e. hostile thoughts rather than hostile behavior) but not to Type A personality. In the context of chronic diseases, Type A personality was even associated with increased survival, especially in coronary heart disease and in diabetes . Indeed, Type A people are goal-oriented and often adhered to medical advice and treatments, which may partially explain better outcomes observed in Type A people suffering from cardiac disease . Beside the Type A concept, the Type D personality defined by Johan Denollet as a personality associating negative affectivity and social inhibition was linked to CHD . Type D people experience extreme difficulty going towards other people, in a manner of social phobia, with an avoiding coping style. It is known that the lack of social support is associated with cardiovascular disease, probably by aggravating the stress response as reported by several studies (Type D stress inflammation). It is now widely accepted that Type D personality is associated with coronary heart disease, thus strengthening the psychobiological links between behavior, stress reactions and the somatic consequences . In addition, the Five-Factor Model of personality defined psychological variations of the normal personality in the 1990s . Thanks to clinical and statistical measurements, a Five-Factor model of personality was obtained, the following five independent factors: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness and neuroticism. In terms of stress reaction and management, the 5-Factor Model showed that extraversion, openness and mainly conscientiousness were protective dimensions in terms of health that depended on direct and indirect causality. Several prospective studies demonstrated, for instance, that conscientiousness was directly associated with lower systemic inflammation, which may explain the better health and the lower frequency of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular events in such people . Psychobiological mechanisms of stress might be regulated in a protective way in some people with positive, dynamic personalities, whereas negative coping strategies may induce deleterious stress responses. In addition, personality traits, such as conscientiousness, could be indirectly associated with better somatic outcomes because of protective behavior. Indeed, conscientious people are good at formulating long-range goals, organizing and planning routes to these goals, and working consistently to achieve them despite difficulties. Then, conscientious people generally listen to health advice, maintain a balanced diet and comply with medical treatments, all of which could indirectly explain better outcomes in such people. In addition, several studies have shown that personality may be associated with health behavior, for instance, conscientiousness was associated with less dangerous behavior (smoking, unbalanced diet, etc.). Numerous arguments thus support the notion that personality traits may modulate psychobiological stress response and health behavior. In this context, paying attention to patients’ personality traits may be important in order to take advantage of motivated personalities to tailor care or to stimulate under-motivated people.

3.2

Emotional psychiatric disturbances

Besides normal psychological variations of personality or coping styles, emotional disturbances can adversely affect people with cardiovascular diseases. Indeed, numerous authors have described the deleterious relationship between anxiety or depression and cardiovascular disease. From an epidemiological viewpoint, between 20 to 30% of depressive people show symptoms of CHD . As previously discussed, direct and indirect mechanisms may mediate the impact of mood disorders on cardiovascular disease. Indeed, major depression is sometimes the cause of psycho-behavioral disturbances such as a loss of interest in carrying out simple tasks (preparing meals, physical activity), which explains the poor lifestyle habits of depressed patients, who cannot summon up enough energy or motivation to consider stopping smoking or changing to a well-balanced diet or maintaining regular physical activity. Depression may occur at any time during a person’s history of heart disease, and is a behavioral factor in the development or aggravation of heart disease as the patient adopts a prolonged sedentary lifestyle, experiences a decline in psychological and physical motivation and tends not to respect the therapeutic regimen. From a biological viewpoint, the stress response could be responsible for cardiac disturbances. During an episode of characterized depression, which in itself is a major factor of stress, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is strongly activated; an increase in serum levels of cortisol and cortisol urinary derivatives indicate the initiation of anti-inflammatory processes that try to restore the disturbed homeostasis . This chronic hypercortisolemia could correlate with the development of atherosclerosis and reflect another biological similarity between depression and heart disease. Indeed, inflammatory pathways may be involved in the association between emotional disturbances and cardiac events via the stress reaction. The inflammatory hypothesis is becoming more and more robust as blood markers of inflammation have been found in both depression and heart disease. In parallel, a decrease in serum levels of Omega-3-type polyunsaturated fatty acids, which has anti-inflammatory properties, has also been observed in depression and cardiovascular disease . The powerful psychological stress associated with mood disorders may cause chronic low-grade inflammation, which is known to be associated with coronary heart disease. Inflammatory processes involved in both mood disorders and cardiovascular disease may be illustrated by lipid dysregulation. For instance, low HDL-cholesterol has been associated with depressive disorder . In addition, molecular and genetic factors linked to oxidative stress and cellular senescence are implicated in anxiety and depression and may exacerbate cardiac disturbances ( Fig. 3 ) . Moreover, genes involved in protection against oxidative stress were up-regulated in anxious and depressed people, thus demonstrating a link between the intensity of anxiety/depression and cellular damage . Other authors have developed evolutionary theories showing that the human genomic system of response to adversity is effective in managing acute stress but not chronic social stress. As this system is not adapted to dealing with contemporaneous stress, the stress response fails and triggers chronic inflammatory activation and metabolic disturbances .