, James B. Galloway2 and David L. Scott2

(1)

Molecular and Cellular Biology of Inflammation, King’s College London, London, UK

(2)

Rheumatology, King’s College Hospital, London, UK

Abstract

Stratified medicine involves identifying groups of patients that are likely to benefit from certain treatment strategies. As inflammatory arthritis patients vary greatly in their prognosis and which treatments they respond to, a stratified approach to their management is needed. A number of clinical and genetic factors have been identified that can be used to predict an inflammatory arthritis patient’s likely prognosis and response to treatment. This chapter will provide an overview of these factors in patients with RA, PsA and AS. It will describe how current International guidelines recommend using these factors to make treatment intensity decisions in inflammatory arthritis patients.

Keywords

Stratified MedicinePrognosticBiomarkersACPAGeneticsWhat Is Stratified Medicine?

Stratified medicine involves the identification of patent subgroups that either have distinct mechanisms of disease or are likely to respond to particular treatments [1]. This approach allows the identification of groups of patients that are most likely to benefit from specific management strategies. In short, it ensures that the right patient gets the right treatment at the right time [1], which is the holy grail of modern clinical practice.

Why Stratified Medicine Is Needed in Inflammatory Arthritis Patients

The inflammatory arthropathies are highly heterogeneous disorders. This heterogeneity can be considered from two perspectives:

1.

Variability in Disease Course

Inflammatory arthritis patients vary greatly in their disease course. Some patients have an aggressive condition, characterised by the early development of radiological damage and disability. Others have a much milder course with normal X-rays and no functional impairment.

2.

Variability in Treatment Responses

Inflammatory arthritis patients vary greatly in their treatment responses. One key example is that one third of RA patients will fail to achieve an ACR20 response after being treated with anti-TNF, which is the first line treatment in active disease not responding to DMARD therapy [2].

This clinical heterogeneity means that for inflammatory arthritis patients to receive high quality care a stratified approach to their management is needed, using clinical characteristics and biomarkers to identify groups of patients particularly likely to respond to specific therapeutic strategies. This stratified approach contrasts with current UK guidelines for inflammatory arthritis patients, which recommend empirical practice managing patients according to the same treatment pathway.

Existing Research in Stratified Medicine in Inflammatory Arthritis Patients

A substantial amount of research relevant to stratified medicine has been undertaken in RA patients. Numerous factors have been shown to associate with disease outcomes and treatment responses. A few research groups have attempted to combine these within prediction models that can be used to inform patient care. The evidence base for stratified medicine in other forms of inflammatory arthritis is more limited, although several factors have been shown to predict disease outcomes and treatment responses in PsA and AS patients. This chapter will therefore primarily focus on stratified medicine in RA. It will provide a brief overview of relevant prognostic factors in non-RA inflammatory arthropathies.

Predictors of Disease Course in RA

Serology

RF and ACPA are established predictors of RA severity. Their presence associates with a more severe disease course characterised by higher rates of radiological damage and extra-articular manifestations. In one observational study of 135 early RA patients, individuals with a persistently positive RF had greater X-ray damage, disease activity and disability and required more aggressive treatment [3]. Similarly in a cohort study of 93 early RA patients identified amongst blood donors, the presence of ACPA prior to and at disease onset associated with worse radiological outcomes [4].

Smoking

There is some evidence that smoking influences RA severity. In one study of 100 early RA patients observed over 24 months smokers had more swollen and tender joints, when compared to non-smokers [5]. The impact of smoking is, however, difficult to assess as it predispose to ACPA formation, which could mediate its effect on disease severity.

Alcohol

Two observational studies have indicated that alcohol consumption may reduce RA severity. In one study of 873 RA cases, more frequent alcohol intake significantly associated with lower DAS28-CRP, Larsen and HAQ scores [6]. In another large observational study of 2,908 RA patients a J-shaped dose-response effect was seen with occasional/daily drinkers having less X-ray progression compared with non-drinkers/heavy drinkers [7].

Social Deprivation

Several studies have observed a correlation between social deprivation and poor RA outcomes. In 869 patients from the Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Study (ERAS) higher social deprivation scores associated with higher HAQ scores and joint counts [8]. This effect may be driven by other lifestyle factors that associate with low socioeconomic status such as smoking.

Gender

RA may be more severe in women. In a prospective study of 225 women and 67 men with seropositive early RA, women had worse disease progression over 2 years with higher DAS28 scores despite receiving similar therapy to men; men had higher remission rates [9]. In another Swedish study women had significantly higher DAS28 and HAQ scores compared with males at all time-points over 5 years [10].

Genetics

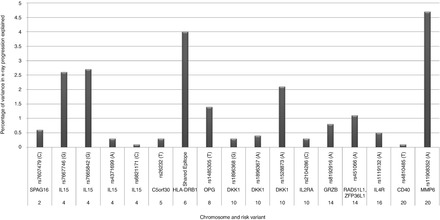

A number of studies have tried to identify genetic markers that can be used to predict RA severity. Most have focussed on genetic associations with X-ray progression. To date 12 genetic loci that associate with radiological progression have been identified and replicated [11]. In a Dutch study of 426 early RA patients, these genetic variants explained approximately 18 % of the variance in X-ray progression, measured as the change in the Sharp-van der Heijde score over 6 years (Fig. 14.1). Most loci had minor effects on X-ray progression. Additionally, their impact was reduced when adjusting for traditional prognostic factors such as age, gender and ACPA, suggesting that their effects may be partially mediated by these clinical factors.

Figure 14.1

Validated genetic predictors of RA radiological progression- their association with 6-year changes in X-ray scores in 239 Dutch early RA patients. The risk allele for each SNP is given in the brackets; X-ray progression measured using the 6-year change in Sharp/van der Heidje scores; the variance of each variant is from a univariate analysis (Figure produced using data reported by Van Steenbergen et al. [11])

Predicting RA Severity

Several research groups have attempted to combine these predictive factors in “prediction models”, which can be used to predict which patients are likely to have rapid radiological progression (RRP). One research group developed a model that included the predictors CRP, erosion score and serology (RF and ACPA). Their model was able to identify groups of patients at a very high or low risk of RRP. The highest risk group had a risk of RRP of 78 %; the lowest risk group had a risk of RRP of just 1 % [12]. Although this suggests stratifying RA patients to prognostic groups is possible, these prediction models have limited abilities to correctly discriminate radiological progressors from non-progressors. Additionally they have mainly been developed and tested in a single dataset and require validation in external cohorts.

Predictors of Treatment Responses in RA

Gender

Research suggests that males probably respond better to methotrexate than females. A systematic review of studies reporting predictors of methotrexate response found that women were up to three times less likely to have a good clinical response when treated with methotrexate compared to men [13].

Data from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register (which collects clinical data on patients receiving biologic drugs in the UK) suggests that women may also respond less well to anti-TNF therapy. In this analysis of nearly 3,000 RA patients female gender associated with a reduced odds of remission with etanercept (OR 0.61; 95 % CI 0.38–0.94) and infliximab (OR 0.60; 95 % CI 0.40–0.89) treatment [14].

Smoking

Several studies have reported that smoking reduces the efficacy of methotrexate and anti-TNF treatment. One example is the Epidemiological Investigation of Rheumatoid Arthritis (EIRA) study, undertaken in Sweden [15]. In this analysis current smokers were less likely to attain a good response when receiving both methotrexate and anti-TNF therapy. Interestingly, a history of previous smoking did not affect treatment responses.

Serology

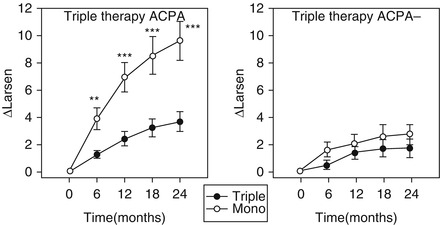

Although RF and ACPA do not clearly affect responses to DMARD treatment there is good evidence that the requirement for intensive combination treatment differs between RA patients with and without ACPA. In an analysis of 431 patients with early, active RA enrolled to the Combination Anti-Rheumatic Drugs in Early RA (CARDERA) trial, only ACPA-positive patients benefited from intensive combination treatment [16]. No benefit beyond monotherapy with methotrexate was observed in ACPA-negative patients. This is demonstrated in Fig. 14.2, which shows mean changes from baseline in modified Larsen scores (measuring X-ray damage) in ACPA-positive and ACPA-negative patients receiving combination treatment or methotrexate monotherapy over 2-years. Combination treatment significantly reduced X-ray progression beyond methotrexate monotherapy at all time-points in ACPA-positive patients. By contrast ACPA-negative patients had minimal X-ray progression irrespective of the treatment strategy used.

Figure 14.2

Impact of ACPA status on responses to combination treatment in 431 early active RA patients in the CARDERA trial. ∆Larsen mean change in Larsen scores from study baseline, Triple triple therapy with methotrexate, prednisolone and ciclosporin, Mono methotrexate monotherapy, standard error bars are shown; *indicates significance between treatment groups at P < 0.05; ** indicates significance between treatment groups at P ≤ 0.01; *** indicates significance between treatment groups at P ≤ 0.001 (Figure adapted with permission from Seegobin et al. (available at http://arthritis-research.com/content/16/1/R13) [16], licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License; figure amended to include only final pair of graphs)

There is some evidence that ACPA status can also predict which patients are most likely to respond to biologic drugs. Rituximab appears more effective in seropositive (RF and/or ACPA-positive) patients, with a meta-analysis of four RCTs demonstrating a significantly greater reduction in DAS28 scores between seropositive and seronegative RA patients at 24 weeks [17]. By contrast TNF-inhibitors seem more efficacious in ACPA-negative disease. In an analysis of the UK Biologics Registry, ACPA-negative patients had a 0.39 (95 % CI 0.07–0.71) greater mean improvement in DAS28 with anti-TNF compared with ACPA-positive patients [18]. Overall the impact of ACPA status on biologic responses is modest, and is of too small an effect size to guide clinical decision making on its own.

Disease Duration

It is established that treating RA in its very early stages improves patient outcomes. This concept, known as the “window of opportunity”, is demonstrated in a meta-analysis of 14 RCTs evaluating predictors of DMARD responses [19]. The percentages of patients attaining an ACR 20 response with active treatment comprised 53, 43, 44, 38 and 35 % for patients with disease durations of <1 year, 1–2 years, 2–5 years, 5–10 years and >10 years, respectively.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree