Developmental dysplasia of the hip is a frequent condition in newborns. Clinical examination using the Barlow/Ortolani tests in newborns or by the finding of limited abduction after the age of 6 weeks may reveal the diagnosis, but neonates with an inconclusive examination or with a risk factor should be referred for further screening. Ultrasonography can detect dysplasia that may not be evident on physical examination or plain radiographs. When dysplasia is identified, treatment should be instituted; in young children, dynamic splinting with the Pavlik harness is safe and effective. Early detection and treatment provides the best long-term outcomes.

- •

Developmental dysplasia of the hip is the most common congenital defect in newborns, with an estimated prevalence ranging from 1 to 30 per 1000 live births. Worldwide, 1 in 1000 children are born with a dislocated hip and 10 in 1000 children are born with hip instability or dysplasia.

- •

The condition occurs with greater prevalence in certain cultures and is rarely observed in others. Cultural traditions, such as swaddling of the infant with the hips together in extension (as is customary in many native North American cultures), have been implicated as important causative factors in these groups.

- •

Approximately 80% of affected children are girls.

- •

The left hip is affected in about 60% of children, the right hip in 20%, and both hips in 20%. It is thought that the left hip is more frequently involved because it is adducted against the mother’s lumbosacral spine in the most common intrauterine position (left occiput anterior); in that position, less cartilage is covered by the bone of the acetabulum and instability is, therefore, more likely to develop.

- •

The most widely accepted theory regarding the greater prevalence in girls speculates that girls may be affected more frequently because of the increased ligamentous laxity that transiently exists as the result of circulating maternal hormones and the additional effects of estrogen that are produced by the female infant’s uterus, although these findings have not been reproduced.

Introduction/overview

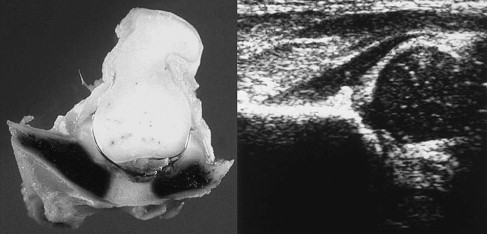

The term, developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), has replaced the term, congenital dislocation of the hip, because it more accurately reflects the full spectrum of developmental abnormalities of the hip joint ( Fig. 1 ).

DDH or dislocation of the hip occurs more often in infants who present in the breech position, whether delivered vaginally or by cesarean section. The in utero knee extension of the infant in the breech position results in sustained hamstring forces regarding the hip with subsequent hip instability. Although breech presentation occurs in less than 5% of newborns, breech position has been noted in up to 32% of children with DDH. Twice as many female infants as male infants present in the breech position, and 60% of breech presentations are noted in firstborn children. Firstborn children are affected twice as often as subsequent siblings presumably because of an unstretched uterus and tight abdominal structures, which may compress the uterine contents. Postural deformities and oligohydramnios are also associated with DDH. The probability of having a child with DDH in at-risk families has been determined by Wynne-Davies to be 6% if there are normal parents and one affected child; 12% if there is one affected parent but no prior affected child; and 36% if there is one affected parent and one affected child.

This condition can result in both subluxation and dislocation of the hip; a subluxated hip is one in which the femoral head is displaced from its normal position but still makes contact with the bony portion of the acetabulum. With a dislocated hip, there is no articular contact between the femoral head and the acetabulum. This definition is based on radiographic findings and does not necessarily reflect the underlying pathoanatomical situation.

Acetabular dysplasia is characterized by a shallow or underdeveloped acetabulum. Dysplasia can exist with or without concomitant instability of the hip and, if untreated, may lead to a poorly located symptomatic hip. An unstable hip is one that is reduced in the acetabulum but can be provoked to subluxate or dislocate (ie, Barlow positive). It should also be noted that there is a significant difference between clinical instability as found on examination and sonographic instability, which is only found on dynamic sonogram testing; it can be difficult to distinguish some normal movements or clicks in healthy hips that have increased joint laxity, which makes it imperative that all newborns who have an equivocal physical examination be referred for further imaging, preferably with ultrasound. Estimates of the incidence range widely owing to the method used to detect the dysplasia, among other factors. Early detection through neonatal screening along with the early initiation of treatment has lowered the rates of treatment-related complications, such as avascular necrosis of the femoral head and neck. DDH is a leading cause of early arthritis. When the cost of the subsequent joint replacement surgery is considered, the impact from this condition is evident on any public health system.

Screening

Neonatal screening for DDH can be performed by clinical examination or ultrasonography. Although neither of these tests carry any significant risk to patients, there is the possibility that universal ultrasound screening will detect several patients with abnormal findings that will resolve completely (ie, a false-positive study); this, combined with the possibility of creating iatrogenic complications with the overtreatment of these possibly normal hips, has created some controversy over the efficacy of universal screening for hip dysplasia. Practices regarding screening vary according to country. In some German-speaking countries, it has been the custom to perform universal screening for many years; however, in the United States, there has been less enthusiasm for universal screening. In fact, although the current clinical practice guidelines of the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends screening for hip dysplasia, the US Preventive Services Task Force recently concluded that “evidence is insufficient to recommend routine screening” for DDH because of the lack of clear scientific evidence favoring screening. These conflicting statements make it difficult for the practicing clinician to make recommendations based on current opinion. A recent study by Mahan and colleagues concludes that “the optimum strategy, associated with the highest probability of having a nonarthritic hip at the age of 60 years, was to screen all neonates for hip dysplasia with a physical examination and to use ultrasonography selectively for infants who are at high risk.” This view is currently the view supported by the Pediatric Orthopedic Society of North America that recommends that all health care providers who are involved in the care of infants continue to follow the clinical practice guideline for early detection of DDH outlined by the American Academy of Pediatrics and is the strategy that is about to be introduced in the United Kingdom.

Physical Examination

All newborn infants should be examined by a physician in the nursery. The history obtained at that first evaluation includes gestational age, presentation (breech vs vertex), type of delivery (cesarean vs vaginal), sex, birth order and family history of hip dislocation, ligamentous laxity, and myopathy. The baby should be relaxed and examined in a warm quiet environment with removal of the diaper. A general examination, beginning at the head, should be performed to detect conditions that are associated with an increased prevalence of DDH, such as torticollis, congenital dislocation of the knee or foot, lower-extremity deformities, and ligamentous laxity.

The evaluation of the hip begins with the observation of both lower extremities for femoral shortening or asymmetry, although it should be noted that asymmetrical inguinal or thigh skin folds can be a normal finding. The Galeazzi or Allis sign is elicited by placing the child supine with the hips and knees flexed. Unequal knee heights suggest congenital femoral shortening or dislocation of the hip joint. Bilateral hip dislocation may be present and may not reveal asymmetry of femoral length or hip-joint motion. An infant with unilateral hip dislocation will eventually exhibit limited hip abduction on the affected side but perhaps not for several months. Each hip is examined individually with the opposite hip held in maximum abduction to lock the pelvis. Gentle, repetitive, passive motion of the hip joint will allow the detection of subtle instability. Soft tissue clicks felt while adducting or abducting the hip in the absence of other abnormal findings have been further evaluated with ultrasound and are considered benign.

The Ortolani and Barlow tests are performed to evaluate hip stability. The infant must be examined in a relaxed state while positioned supine on a firm surface. Each hip is examined separately. To perform the Ortolani test on the left hip, the examiner’s right hand gently grasps the left thigh with the middle or ring finger over the greater trochanter and the thumb over the lesser trochanter. The examiner’s left hand is used to stabilize the infant’s right hip in abduction. The examination is initiated by slowly and gently abducting the left thigh while simultaneously exerting an upward force on the left greater trochanter. Abduction of each hip should be symmetric. The sensation of a palpable clunk when the Ortolani maneuver is performed represents mechanical reduction of the femoral head into the confines of the acetabulum, signifying a dislocated but reducible hip. The process is then repeated on the right hip with the left hip locked against the pelvis in abduction. The infant is positioned similarly for performance of the Barlow test; however, the thumb is positioned at the distal medial thigh and is used to apply a gentle lateral and downward force at the hip joint in an attempt to dislocate the femoral head from the acetabulum. When the hip is displaced from the acetabulum, the hip is described as dislocatable. When the Barlow test results in positioning of the femoral head within the confines of the acetabulum, the hip is described as subluxatable. After 3 months of age, the Ortolani and Barlow tests become difficult to elicit because progressive soft tissue contracture evolves and the so-called secondary signs develop the risk of restriction of abduction, leg length asymmetry, and a limp (after walking age). The secondary signs may not appear until after 9 months of age.

Radiographic Evaluation

In normal newborns with clinical evidence of DDH, routine radiography of the hips and pelvis may be confirmatory, but a normal radiograph does not exclude the presence of instability; in fact, the cartilaginous nature of the hip joint infers little value to normal radiographs. The current gold standard for imaging of the neonatal hip is ultrasonography, as described by Graf and subsequently by Novick and Clarke and Harcke.

Ultrasonography

Diagnostic ultrasonography uses a transducer that functions as a transmitter and a receiver of acoustic energy. Ultrasonography of infant hips uses a real-time scanning technique in which ultrasonographic pulses are transmitted into the body and are received rapidly enough so that the movement of mobile anatomic structures can be observed directly. Ultrasonography offers distinct advantages compared with other imaging techniques. First, unlike plain radiography, it can distinguish the cartilaginous components of the acetabulum and the femoral head from other soft tissue structures. Second, real-time ultrasonography permits multiplanar examinations that can clearly determine the position of the femoral head with respect to the acetabulum; thus, it provides the same type of information that can be obtained with arthrography, computerized tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging but at a lower cost. Third, ultrasonography does not require sedation and does not involve ionizing radiation. Finally, unlike other techniques, it allows observation of changes in hip position with movement ( Figs. 2 and 3 ).

The pioneering work by Graf emphasized a morphologic approach to the ultrasonographic examination based on a coronal image obtained through a lateral approach when the infant is in the lateral decubitus position; Novick and then Harcke and colleagues developed a technique based on a dynamic multiplanar examination that assesses the hip in positions produced by the Ortolani and Barlow maneuvers. The dynamic approach can also be used to assess acetabular morphology and development; however, it places the greatest emphasis on the position and stability of the femoral head. These two approaches are not in conflict with one another; currently, most clinicians perform what has been termed the dynamic standard minimum examination, which includes assessment in the coronal plane with the hip at rest and assessment in the transverse plane with the hip under stress. With regard to the specifics of these elements, some options are left to the preference of the examiner. It should be noted that the measurement of acetabular characteristics, such as angular measurement of acetabular landmarks, is considered optional.

The static technique is performed with the infant in the lateral decubitus position and the hip in 35° of flexion and 10° of internal rotation. Morphology is assessed by describing basic anatomic features and by angular measurement. The dynamic hip examination is performed following an examination of the hip at rest. The hip is checked for instability, which can be quantified by measurement of the degree of displacement of the femoral head. The infant lies on his or her side in the positioning apparatus and the transducer is positioned over the hip, which is then adducted and pushed superiorly to demonstrate instability. Angular measurements serve to confirm the diagnosis indicated by the morphologic description and provide a quantitative parameter for comparison of findings ( Fig. 4 ).

A coronal image of the hip is obtained and 3 lines are constructed: a vertical line drawn parallel to the ossified lateral wall of the ilium, termed the base line; a line drawn from the inferior edge of the osseous acetabulum (the inferior iliac margin) at the roof of the triradiate cartilage to the most lateral point on the ilium (the superior osseous rim), termed the bony roofline; and a line drawn along the roof of the cartilaginous acetabulum, from the lateral osseous edge of the acetabulum to the labrum, termed the cartilage roofline. Two angles are calculated. The α angle is formed by the intersection of the base line and the bony roofline. The lower limit of normal for the α angle is 60°. This angle reflects osseous coverage of the femoral head by the acetabulum; the smaller the angle the greater the degree of dysplasia. The β angle is formed by the intersection of the base line and the cartilage roofline. The upper limit of normal for the β angle is 55°. The β angle reflects cartilaginous coverage of the femoral head; the greater the angle the greater the degree of dislocation.

Graf has classified hips according to the measurements based on the degree of femoral head displacement and the associated deformation and growth retardation of the acetabular roof. Type I indicates a normal hip with a good cartilaginous and osseous roof (an α angle of 60° or more). Type IIa represents an immature hip in an infant who is younger than 3 months with delayed ossification but an adequate cartilaginous roof and an α angle of 50° to 59°. Type IIb refers to a hip with delayed ossification in an infant older than 3 months with a rounded osseous acetabular promontory; an α angle of 50° to 59° and a β angle of more than 55°. Types IIc, III, and IV are always pathologic. In types III and IV, the bone molding of the acetabulum is severely deficient or poor and there is lateralization of the femoral head. The α angle is 43° to 49° in type IIc and less than 43° in types III and IV. The β angle is 70° to 77° in type IIc and more than 77° in type III and IV. Angular measurement is subject to interobserver and intraobserver error. In type IV, the cartilaginous acetabulum is interposed between the femoral head and the ilium. Regardless of the hip type, testing for instability should always be performed.

The technique of dynamic hip ultrasonography incorporates motion and stress maneuvers that are based on accepted clinical examination techniques ( Fig. 5 ). With the dynamic method, an attempt is made to visualize the Barlow and Ortolani maneuvers on the ultrasonography screen. The technique depends on ligamentous or capsular laxity; as with the physical examination, the study quality depends on the operator performing the stress test. In a normal hip, the femoral head is well positioned and stable under stress. In the first few weeks of life, the femoral head is reduced in the acetabulum at rest but it may show slight displacement (physiologic laxity) under stress; this should resolve by the time the infant is 4 weeks of age. Although subluxation implies displacement of the head from the acetabulum, the head is not completely dislocated. In more severe forms of hip dysplasia, the femoral head may be dislocated from the acetabulum at rest (but may be reduced with maneuvers) or it may be displaced by means of maneuvers. An image is obtained with the hip flexed to 90° as posterior stress is applied to the knee with the palm of the hand the Barlow provocative test (see Fig. 3 ); any resultant subluxation is then noted (see Figs. 4 and 5 ). It should be remembered that 4 to 6 mm of subluxation is normal during the first few days of life. If the hip subluxates or dislocates, reduction is attempted (the Ortolani maneuver).