Staying Out and Getting Out of Trouble During Total Knee Arthroplasty

Many problems or mishaps can be encountered during routine and not-so-routine total knee arthroplasty (TKA). In this chapter, I address several of these and offer potential solutions.

Choosing the Correct Incision

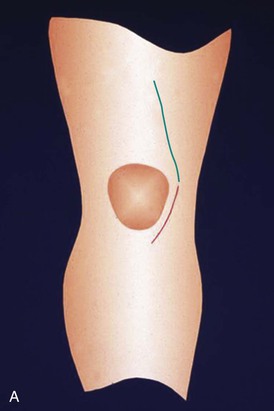

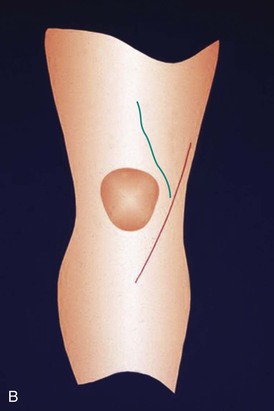

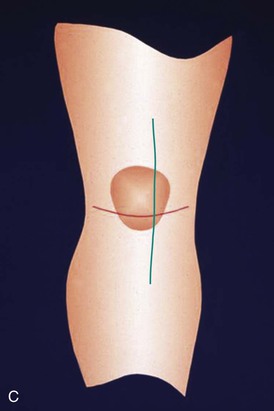

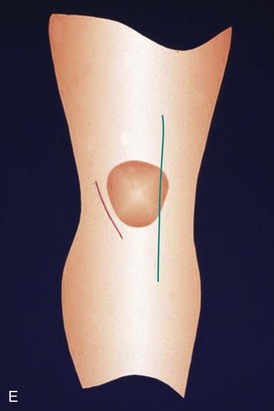

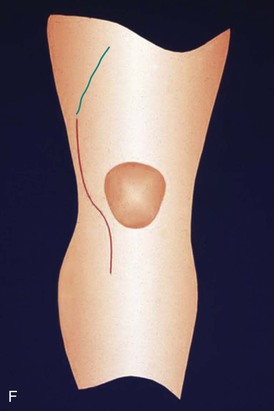

Wound necrosis after TKA can be a minor inconvenience or a major disaster that can lead to secondary infection and potential loss of the knee replacement. Necrosis is most likely to occur in the setting of a knee with prior incisions. It is imperative therefore for the surgeon to respect old incisions around the knee and choose the right incision for the arthroplasty. Unlike the hip, the knee does not tolerate parallel incisions or crossing incisions (Figure 14-1). The ideal skin incision for a knee without prior surgery is vertical and relatively straight (see Chapter 3). I prefer an incision that is approximately 15 cm long and begins over the midshaft of the femur, crosses the medial third of the patella, and ends just medial to the tibial tubercle. In the early 1970s, a routine skin incision was parapatellar, curving around the medial border of the patella to create a laterally based skin flap. A certain number of patients suffered some necrosis at the apex of the flap, and this led us to straighten the incision. The vascular supply to the skin around the knee appears to be much more tolerant of medially based flaps than laterally based flaps. The knee most vulnerable to necrosis is one that has a long prior lateral incision that is followed by a parallel, more median incision (Figure 14-2).

When parallel incisions are necessary, the surgeon should make the bridge between the two incisions as wide as possible or consider using the lateral incision and elevating a medially based flap for a medial arthrotomy. If the alignment of the arthritic knee is in valgus, this may be an excellent indication for a lateral arthrotomy where the patella is everted medially.1

In general, in the presence of prior incisions, the surgeon should use the most lateral one that is viable or the most recent one that successfully healed. In unclear situations, a sham or delayed incision technique can be considered. The sham incision was advocated by my associate, F. Ewald. In this technique, the skin incision is made and the flaps are elevated in preparation for the arthrotomy. A tourniquet, if used, is deflated or uninflated. The medial and lateral skin edges are carefully inspected for active bleeding. If blood flow is equivocal, the procedure is aborted and consultation obtained with a plastic surgeon.

The delayed incision technique was advocated by J. Insall. The skin incision is made, the skin flaps are elevated for the arthrotomy, and then the wound is closed regardless of the clinical appearance. Assuming no skin necrosis has occurred, the knee arthroplasty is carried out through the same incision 4 to 6 weeks later. It is thought that this technique not only tests the viability of the skin flap but also promotes increased collateral circulation secondary to the healing process.

Tissue expanders have been recommended in the presence of tight adherent skin and subcutaneous tissue.2 I have used this technique several times with excellent results.

Figure 14-3, A to F shows diagrams of the most frequently encountered prior knee incisions accompanied by a diagram of the most likely approach I would use in each case.

Dealing with Skin Necrosis

When skin necrosis occurs, I believe it is extremely important to keep the skin sealed for as long as possible and allow the capsular closure to seal as well. To help accomplish this, I stop all range-of-motion exercises and immobilize the knee in a splint that is easily removable so I can inspect the wound on a daily basis. If the wound remains completely dry for 10 days, I start range-of-motion exercises and assess the size of necrosis, which should have fully declared itself by this time. If any drainage from around the area of necrosis does not slow and cease within several days of surgery, a plastic surgery consult is obtained for immediate intervention.

Several options exist for the treatment of skin necrosis around a TKA. If the area is small and dry, it can be left to granulate beneath the eschar. If the area is relatively small and the skin pliable, it can be excised and closed primarily.

Once the joint capsule is sealed, the area also could be excised and a split-thickness skin graft applied. If the area is extensive and the joint unsealed or exposed, a gastrocnemius muscle flap may be required, followed by a split-thickness skin graft.

I have twice encountered a situation in which patellectomy allowed resolution of a significant skin necrosis problem. Both cases involved severe preoperative deformities in patients in whom an extensive lateral release had been performed with sacrifice of the lateral genicular vessels. In both cases, a bone scan showed no uptake in the patella, indicating it was avascular.3 The patella is always more than 2 cm thick; thus removing it might provide sufficient laxity in the capsule and skin to allow for primary closure of both layers as it did in both these cases.

A Draining Wound

Persistent wound drainage after TKA should not be tolerated. I change the operative dressing on the second postoperative day. If any wound drainage is present, I carefully inspect the suture line for gaps in the skin closure. If gaps are present, the skin is cleaned with povidone-iodine and alcohol and then benzoin is applied along its edges followed by Steri-Strips to reseal the wound. This maneuver might have to be repeated for another day or two. Flexion exercises are suspended until the wound is dry for 24 hours. If drainage still persists, I believe that treatment should be aggressive and the patient returned to the operating room for minor wound débridement, irrigation, and primary closure.

To be sure that the drainage does not represent a deep problem, the knee joint is aspirated through a remote site. The fluid is sent for cell count, differential, and aerobic and anaerobic cultures. Oral prophylactic antibiotics are begun; I usually use 500 mg of a second-generation cephalosporin 4 times daily. I always close knee wounds with interrupted nylon sutures (see Chapter 3). In the operating room, the knee area is sterilely prepared and draped. Two or three sutures are removed from around the area of drainage. A subcutaneous culture is obtained. The wound is thoroughly irrigated and a primary closure performed with interrupted 3-0 nylon vertical mattress sutures. The skin edges are freshened by removal of 1 or 2 mm of tissue, if necessary. The procedure is performed under local anesthesia using 1% lidocaine. Flexion exercises are suspended for 1 or 2 days until it is apparent that the wound is sealed.

Dealing with Excessive Suction Drainage

It is somewhat controversial whether or not a TKA should be drained. I remain an advocate of low-suction drains for the first 24 hours after surgery to minimize wound swelling. The published studies indicating that drains may not be necessary are based on only several hundred cases. I firmly believe that in 1000 or more cases, a rare complication resulting from not using a drain will occur that will cost more in actual dollars to heal the wound than would have been spent on drains for all 1000 patients.

When drains are used, at times drain output is excessive in the first few postoperative hours. I have a simple treatment algorithm that seems to work well. We have all observed the fact that when the tourniquet is deflated, the knee bleeds less in flexion than in extension. If the drain output is large, simply flex the knee for 30 minutes and the output usually slows. If this method fails or is too painful for the patient, I clamp the suction drain for 30 minutes. If this is insufficient, I clamp and unclamp the drain for several cycles. In extremely rare, persistent cases, I remove the drain and apply a moderate compression dressing. Persistent bleeding may, of course, be due to a latent bleeding disorder or one created by the method of prophylactic anticoagulation; these possibilities must be checked.