INTRODUCTION

Congratulations! You are now in the “home stretch” of the endurance event that will enable you to effectively provide the exercise prescription for your patients. If you have been able to motivate and assist your patients from the “couch” up to the ACSM/AHA minimum recommended exercise levels, you have achieved the most difficult, yet most important and influential, part of your patient’s transformation from a sedentary to an active lifestyle. It is our hope that by this stage both you and your patients are already reaping some of the many mental and physical health benefits of a physically active lifestyle. Your role in your patient’s transformation is not quite finished yet, however. You will still need to discuss with him how to

maintain or even

increase his new level of fitness. This phase in the exercise prescription is referred to as the “Staying Active” Phase (see

Figure 9.1).

Your patients who have reached the ACSM/AHA minimum recommendations (

1) should feel proud—they have joined the minority of Americans who are gaining benefits from being physically active. As you have read and will witness when working with some of your patients, this is no small feat; yet, as you know, the benefits cannot be overstated. For many patients, maintaining this minimum level will suffice. However, encouraging them to make periodic increases, or at least changes, in any of the FITT components, will add to the benefits gained from regular exercise.

Some of your patients will have actually “caught the exercise bug” and will be keen to increase their exercise program. For others, you may recommend that for weight loss or other health reasons, their exercise program be increased above the recommended minimum levels. In this chapter, we will first address maintaining an exercise program and will then move to increasing the program. This book is designed to assist you, the clinician, in working with the average patient. If your patient has aspirations of running marathons or competing in other more advanced physical activities, you may want to recommend that he consult racing-specific literature, or even work with a coach or exercise trainer.

As we have said on more than one occasion, in becoming and staying a regular exerciser, one size definitely does not fit all. In

Chapter 10, we will provide an alternative approach to providing the exercise prescription—a more structured approach, than the individualized approach that we are taking in this chapter as well as in

Chapter 8.

MAINTAINING AN ACTIVE LIFESTYLE

Many of the principles behind maintaining an exercise program are similar to those in beginning a program. A main difference, however, is that once your patient has reached the maintenance stage, she has already incorporated the time to exercise regularly into her daily routine and has begun to reap the benefits of the exercise program. Despite this, your patient will still need to spend some time and effort ensuring that she continues the exercise program. The key to maintaining an exercise program is maintaining motivation. This can be done in a variety of ways, including adding variety to the program, rewarding oneself for reaching certain milestones, taking occasional breaks when necessary, and maintaining the routine and consistency of the program. Please see

Chapter 15 for a more extended treatment of “How to Make Regular Exercise Fun.”

Motivation and Encouragement

It is not hard to appreciate that your patient may eventually get bored with doing the same exercise routine day after day, month after month. This boredom is not only mental, but also physical. Your patient’s muscular and neurological systems also need variety in order to continue to benefit maximally from exercise. (See

Table 9.1, Advantages of Training in More Than One Type of Exercise.) This variety does not have to take the form of an increase in activity, just a change in type.

Table 8.3 and

Chapter 11 present numerous different types of physical activity that your patients can engage in.

Substituting different activities into an exercise routine, like swimming every Thursday or walking or running outside in the summer and using cardiovascular equipment at the gym in the winter can help your patient to keep up his motivation and to continue to get the maximal physiological benefit from exercising. Alternatively, variety can come from variations in intensity, duration, or routes. For example, your patient could increase his walking speed between certain light poles, could add a hill into one of his routes, or could increase the duration of one or two exercise sessions and decrease a few other sessions, maintaining a frequency of five days each week, for a total of at least 150 minutes each week.

Another strategy that exercisers at all levels can try is the “just getting out the door” approach to dealing with motivationally difficult days. On a day when your patient is feeling “too tired” or “just not motivated” to exercise, ask her to commit to at least starting the workout. This could mean setting an initial goal of walking to the corner of the street or getting to the gym. Often, by the time your patient has taken this initial step, the motivation has kicked in again, and she can persuade herself to keep going a little further. This approach also works during a workout. In this case, after achieving the goal of getting out the door, the patient is encouraged to set a very small goal such as walking to the next lamp post. Then, feeling better having reached the goal, the patient can set another goal of making it to the next lamp post. We have even seen

marathon racers use this approach to get through difficult miles in a race—one step, or one tiny goal at a time.

Motivation may also come from pursuing play activities. These may range from competitive sports, to include active video games that involve dancing and simulated sports activities, to trying a new activity or playing actively with the kids. When motivation is lagging, any of these activities may be successful in just getting the patient moving again.

Throughout this process your patient is encouraged to acknowledge his successes and his commitment to a healthier lifestyle. When your patient reaches his goal of exercising at the ACSM/AHA-recommended minimum, you should provide positive reinforcement, and he should find some way to acknowledge himself for his own success. He should also be encouraged to consider setting a new goal, e.g., to maintain the current level for the next six months, to increase his total weekly exercise time from 150 minutes to 200 minutes, or to train for a 5-kilometer race. By setting a new target, even if it is “just” to maintain the same level, he will have something to motivate himself to achieve. Assuming he reaches the new goal, he will have something to celebrate when that next goal is reached.

Keeping Track of Exercise: Logbooks

One way to track progress toward a goal is to regularly record exercise sessions in a logbook. We recommend the use of a simple log from the initiation of an exercise program, as it provides immediate feedback to both the patient and to you. As she progresses into the staying active phase, the log becomes more important. It adds motivation and discipline, and can help a patient to get back on track after short breaks in the exercise program.

For patients who decide to progress beyond the ACSM/AHA minimums, it is a useful way to ensure that they do not progress too fast. Running and other sports shops or bookstores offer a variety of logbooks; or your patient can keep track in a diary, or calendar, or electronic PDA. The information tracked depends on the goals of the patient, and can be as simple as number of minutes of exercise on a given day. If the patient so chooses, it can also include other variables, such as the patient’s weight and heart rate (resting or exercising heart rate), type of exercise, how the patient felt that day, the intensity of the exercise, or the weather outside.

More sophisticated pedometers and accelerometers can now measure the number of minutes of low-intensity movement, moderate-intensity walking, and vigorous-intensity running and wirelessly record this in a Web site that tracks your patient’s activity levels.

Regularity and Consistency

As we have stressed throughout this book, the

regular part of “regular exercise” is the more difficult component. By reaching the ACSM/AHA minimum exercise

recommendations, your patient has likely established a routine in which exercise is part of daily life. Maintaining this consistency in exercising is an important factor in maintaining an active lifestyle. Even the seasoned athlete can fall into the trap of, “Oh well, since I missed my run on the weekend, another day off won’t make much difference.” Physiologically, missing a few runs will not make a difference in the long run, but psychologically, skipping exercise sessions can lead your patient down the slippery slope toward quitting.

Taking Breaks

At the same time, taking

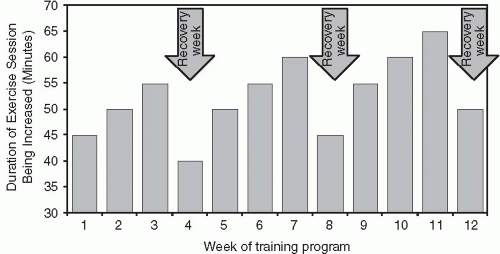

planned breaks in one’s exercise program are also important. Having stressed the importance of routine and consistency, advocating for breaks may sound like a conflicting message. Planned breaks, such as during a short vacation, or after a goal has been reached, help to revitalize both the mind and the body. The break can act as a reward and as a tool to help re-motivate your patient. A short break (one to two weeks) can be good not only for the mind, but also for the body. When muscles are stressed, particularly through vigorous-intensity exercise, they require recovery time to “assimilate the training”—to recover and strengthen from the activity that they have done. The more intensively your patient is exercising, the more benefit he will get from breaks. This is discussed further in the following section. See

Figure 9.2, Step-Wise Exercise Progression that details relative rest periods or breaks every several weeks.

Another time in which rest breaks are necessary is when injury and/or illness occur. Patients should be encouraged to “listen to their bodies,” to become more observant of the body’s messages telling them when it is getting injured. Patients will need to learn the distinction between Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS) (see

Chapter 7) that presents as muscle pain beginning approximately 24 hours after a new or increased intensity of activity, and an acute injury that induces pain more quickly. Alternatively, repeatedly stressing a particular joint, such as the dominant elbow in tennis players, can result in overuse injuries. These chronic injuries are due to repetitive stress to the muscles, tendons, bones, and joints. See

Table 9.2 Injury Prevention Strategies. Particularly with overuse injuries, the earlier a potential one can be “caught” and rested, the shorter the time that the affected area will have to be rested so that the injury can heal. For example, if a patient starts to notice a “nagging” in her calf when she walks briskly, she should try to find an activity that does not aggravate her calf. This may simply be walking at a slower pace, or may involve trying a different sport, such as swimming, for a week. If these alternatives are not possible or continue to aggravate her calf, she should stop exercising for a short period (one to two weeks), and seek medical attention if the problem does not go away. If she tries to continue exercising through the pain, the injury could worsen, resulting in pain and discomfort during other activities, and a forced break from the aggravating exercise for a longer period (one to two months).

Clearly, during serious illness, patients should not exercise. During illnesses such as a mild cold or headache, light exercise may be beneficial. As a rule of thumb, if the symptoms of the cold or upper respiratory infection are “above” the shoulders, it is generally fine to continue exercise. However, constitutional symptoms below the neck may best be addressed by rest until they resolve. Elevated resting heart rates (measured upon awakening) are another rough measure that relative rest is indicated. Again, encourage your patient to listen to his body. If exercising makes him feel better during mild illness, there is no reason to stop. If, however, he feels worse exercising, then a break is indicated.

In addition to planned breaks and illness- or injury-related breaks, other obstacles will result in unplanned breaks in your patient’s exercise program. Help your patient to accept that these breaks are inevitable and are not damaging to the program unless they result in your patient losing motivation and having difficulty returning to the exercise program, or they lead to de-conditioning which begins after several days of inactivity. Therefore, ensuring that patients are able to get back to their regular exercise routine after a break—either a planned break or an inevitable, unplanned one—should be a priority for both you and your patient.