Fig. 4.1

A combination of wrist extension and radial inclination leads to opposed constraints on the scaphoid

Fig. 4.1′

The extension and radial inclination of the injury mechanism put constraints on the radius, the scaphoid, and the scapholunate ligament. In this mechanism, the scapholunate ligament forbids the proximal part of the scaphoid from going to palmar

The posterior part of the radius presses on the scaphoid that transmits important constraints on the scapholunate ligament, which is opposed to the movement of the scaphoid’s proximal part towards palmar.

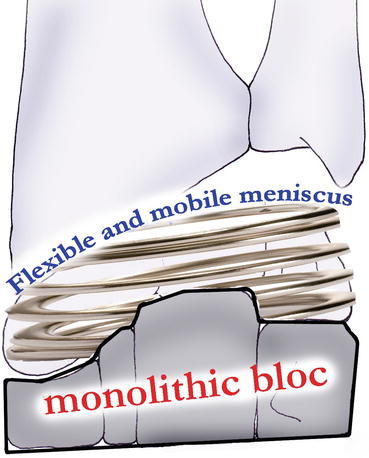

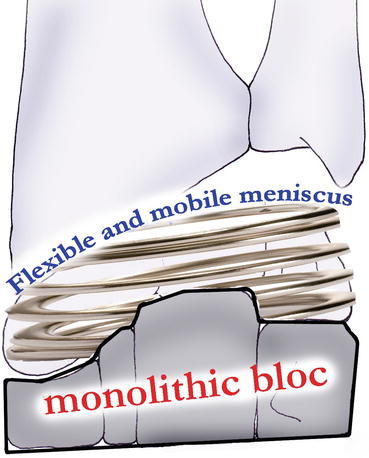

The first carpal row is like a “mobile meniscus” that absorbs axial constraints as long as it forms a coherent set (Fig. 4.2).

Fig. 4.2

The first carpal row plays the role of a “flexible and mobile meniscus” that absorbs the longitudinal constraints from the carpus

When the scapholunate ligament breaks, the first carpal row is disunited and the whole carpal stability is compromised [5]:

The scaphoid goes to flexion because of longitudinal constraints.

The lunate goes to extension because of the triquetrum (dorsal intercalated segment instability).

The scapholunate space increases, creating a scapholunate diastasis (Fig. 4.3).

Fig. 4.3

The rupture of the scapholunate ligament is catastrophic for the cohesion of the first carpal row

These biomechanical changes lead to a decrease of the carpus height, as the scaphoid and lunate reduce their working distance. This causes the extrinsic ligamentous systems to become slack and the passive stability of the carpus to be compromised (Fig. 4.4) [5].

Fig. 4.4

The modifications of organization in the first carpal row after injury of the scapholunate ligament lead to a decrease of the carpus height, which causes slackness in the extrinsic capsular systems

The biomechanical changes in the wrist after this type of injury lead to degenerative phenomena [6], even if it’s difficult to predict when they are going to appear.

4.2 Clinical and Paraclinical Signs

An early diagnosis is a crucial factor for the patient’s recovery as surgery is more difficult with an old injury [7].

4.2.1 Clinical Signs

The clinical exam allows finding several elements that, unfortunately, aren’t specific to injuries of the scapholunate ligament:

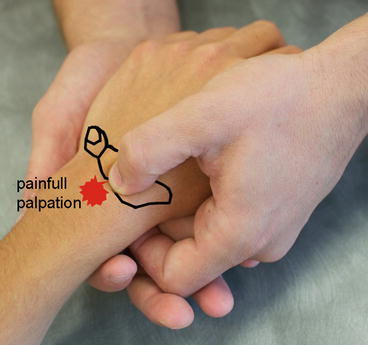

Pain on the radial side of the wrist, most often with intense pain when palpating the scapholunate interline (Fig. 4.5)

Fig. 4.5

Palpation of the scapholunate interline

Clicking and snapping when mobilizing, mainly related to the disconnection of the scaphoid and lunate

Important strength loss

Mobility loss (later)

There also exist some clinical tests that can help the assessment:

Scapholunate instability test: it consists in applying opposite glidings on the scaphoid and the lunate. Pain or abnormal movement guides the therapist towards an injury of the scapholunate ligament (Fig. 4.6).

Fig. 4.6

Scapholunate instability test

Evaluation of the scaphoid dynamic (bell sign): it consists in assessing the scaphoid’s mobility with the wrist in radial and ulnar inclination. The therapist places his/her thumb at the level of the scaphoid’s tubercle and applies a radial and ulnar inclination in the wrist. If the scaphoid dynamic is good, the therapist feels the tubercle sticks out in radial inclination (the scaphoid goes to flexion) and goes in ulnar inclination (the scaphoid goes to extension) (Fig. 4.7).

Fig. 4.7

Evaluation of the scaphoid dynamic

Watson’s test (scaphoid shear test): in this test, the therapist is facing the patient in an “arm wrestling” position. The therapist’s index or fingers are placed on the dorsal side of the scaphoid’s proximal part, and his thumb is on the palmar tuberosity. The other hand maintains the metacarpals. A firm pressure is applied on the palmar side of the scaphoid, while the wrist is placed in ulnar inclination, which makes the scaphoid go to extension. When passing in radial inclination, the scaphoid can’t flex as it’s maintained by the therapist’s thumb. In case of scapholunate injury and in patients with great laxity, the scaphoid tends to go backward under the posterior part of the radius and therefore contacts with the therapist’s index which revives pain. Pain can be present on its own or be associated to snapping. When pressure is released, the scaphoid gets back to its normal position, sometimes with an audible “thunck.” In some cases, the lack of mobility with comparison to the same side can express an edematous and synovial reaction. To avoid false positives that are still too frequent, we must first put pressure on the posterior side of the scaphoid and see if there’s spontaneous pain. Even if it’s the most well-known test, it has low sensitivity and specificity. It’s positive in only 20 % of normal individuals. Lane proposed a modification (scaphoid shift test) realizing only an anteroposterior translation, which would increase the test’s sensitivity.

4.2.2 Paraclinical Signs

After a complete clinical exam, these signs will confirm or reject the injury of the scapholunate ligament and its stage (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1

Recapitulative table of the scapholunate instabilities (according to Ph. Saffar)

STAGE | EXAM |

“Predynamic” | Clinical diagnosis, normal X-ray |

Dynamic instability | Clinical diagnosis + dynamic X-ray |

“Static” or constant (N. Barton) | Simple FP X-ray + control of the cartilage: arthroscan or arthroscopy |

Static with arthrosis: arthrosis radio-scaphoid + luno-capitate (SLAC) | Simple FP X-ray ± control of the cartilage: arthroscan or arthroscopy |

4.2.2.1 X-Ray

Static

Frontal X-rays assess:

The scapholunate diastasis (or gap), greater than 3 mm in case of injury

The ring sign that means the scaphoid tilts in flexion

The carpal height that can be reduced as the scaphoid tilt in flexion and the lunate tilt in extension decrease their working distance

Lateral X-rays assess:

The scapholunate angle that is normally lower than 70° (Fig. 4.8)

Fig. 4.8

Scapholunate angle superior to 70° that shows an injury of the scapholunate ligament

The displacement of the lunate in extension or DISI (dorsal intercalated segment instability)

Fist Closed

The patient clutches his fingers with the maximal intensity, which makes the capitate go towards the scapholunate space. If the scapholunate ligament is ineffective, it creates a diastasis between the scaphoid and the lunate (Fig. 4.9).

Fig. 4.9

An X-ray of the clamping hand can show a scapholunate diastasis

Dynamic

Dynamic X-rays in flexo-extension and inclinations of the wrist highlight injuries of the scapholunate ligament with rupture of the Gilula’s lines, which don’t appear on static X-rays. We talk about dynamic scapholunate instability.

4.2.2.2 Scintigraphy

In this stage, if no clinical or radiological element is accepted, a negative scintigraphy excludes serious injuries.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree