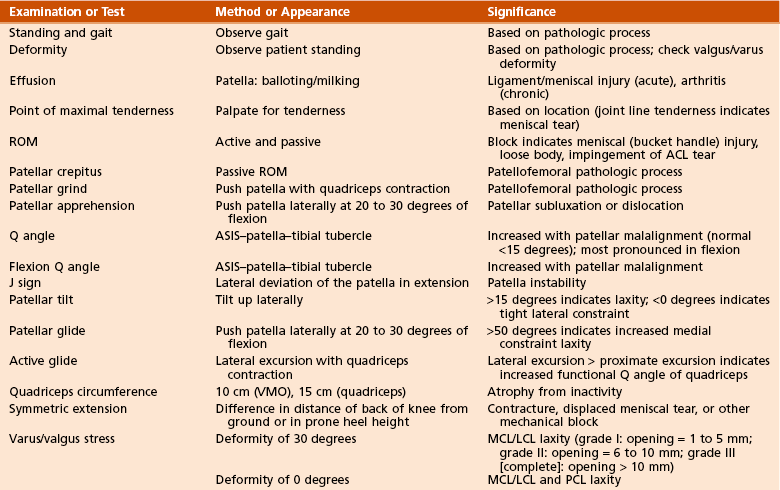

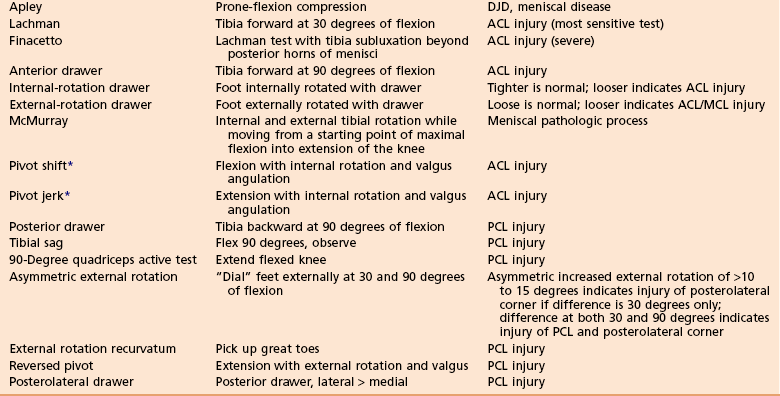

Chapter 4 SECTION 2 THIGH, HIP, AND PELVIS SECTION 3 LEG, FOOT, AND ANKLE V. Impingement Syndrome/Rotator Cuff Disease VI. Superior Labral and Biceps Tendon Injuries VII. Acromioclavicular and Sternoclavicular Injuries IX. Calcifying Tendinitis and Shoulder Stiffness SECTION 8 MEDICAL ASPECTS OF SPORTS MEDICINE I. Preparticipation Physical Examination IV. Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness V. Cardiac Abnormalities in Athletes VI. Metabolic Issues in Athletes VIII. Female Athlete–Related Issues 1. Hinge joint that also incorporates both gliding and rolling, which are essential to its kinematics 2. See Chapter 2, Anatomy, for a thorough discussion of knee anatomy. 4. Medial structures of the knee (three layers) (Table 4-1; Figure 4-2) Table 4-1 MCL, medial collateral ligament. Note: The gracilis, semitendinosus, and saphenous nerves run between layers I and II. 5. Lateral structures of the knee (three layers) (Table 4-2; see Figure 4-2) Table 4-2 Lateral Structures of the Knee LCL, lateral collateral ligament. 1. Ligamentous biomechanics: The role of the ligaments of the knee is to provide passive restraints against abnormal motion (Table 4-3). Table 4-3 Biomechanics of Knee Ligaments 2. Structural properties of ligaments: The tensile strength of a ligament, or maximal stress that a ligament can sustain before failure, has been characterized for all knee ligaments. However, it is important to consider age, ligament orientation, preparation of the specimen, and other factors before determining which graft to use. 3. Kinematics: The motion of the knee joint and interplay of ligaments have been described as a four-bar cruciate linkage system (Figure 4-5). 1. Complete history of the injury 2. Clarification of mechanism of injury 4. Important key historical points (Table 4-4) Table 4-4 Key Historical Points That Indicate Mechanism of Injury ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; PCL, posterior cruciate ligament. 1. Key examination points are shown in Table 4-5. Table 4-5 2. Examination performed with the patient under anesthesia may be helpful in some cases. C Instrumented measurement of knee laxity 1. KT-1000 and KT-2000 Knee Ligament Arthrometers (MEDmetric, San Diego, California) are the devices most commonly used for standardized laxity measurement. Table 4-6 Knee Injuries: Radiographic Findings 2. Stress radiographs: These are useful for evaluating injuries to the femoral physis (to differentiate from MCL injury) and are becoming the “gold standard” in diagnosing and quantifying PCL injury. They can also be used to evaluate LCL and PLC injuries. 3. Nuclear imaging: Technetium-99m bone scans are useful in diagnosing stress fractures, early degenerative joint disease, and complex regional pain syndrome. 4. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): This has become the imaging modality of choice for diagnosis of ligament injuries, meniscal disease, avascular necrosis, spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee, and articular cartilage defects and has replaced the use of arthrography. On coronal MRI sequences, meniscal root tears are seen as a band of low-signal fibrocartilage. Occult fractures of the knee can be identified by a double fluid-fluid layer, which signifies lipohemarthrosis. 5. Magnetic resonance arthrography: Intraarticular magnetic resonance arthrography is the most accurate imaging method for confirming the diagnosis of repeated meniscal tears after repair. 6. Computed tomography (CT): CT has been replaced largely by MRI, but it is still useful in the evaluation of bony tumors, patellar tilt, and fractures. CT has been advocated as a tool to assist in operative planning for patellar realignment by allowing measurement of the tibial tuberosity–trochlear groove (TT-TG) distance; authors recommend distal realignment procedures for a TT-TG distance exceeding 20 mm. MRI can also be used to measure TT-TG distance. 7. Arthrography: This technique was useful historically for the diagnosis of MCL tears and has been supplanted by MRI. However, it can be useful when MRI is not available or tolerated by the patient, and it can be combined with CT. 8. Tomography: Tomograms are preferred to CT in the evaluation of tibial plateau fractures at some medical centers. 9. Ultrasonography: This technique is useful for detecting soft tissue lesions about the knee, including patellar tendinitis, hematomas, and extensor mechanism ruptures, in some centers. Ultrasonography has begun to be used to evaluate meniscal tears but is not as sensitive as MRI. E Arthrocentesis and intraarticular knee injection See Supplemental Images on expertconsult.com. 1. The “gold standard” for the diagnosis of knee disease 2. The benefits of arthroscopic over open techniques include smaller incisions, less morbidity, improved visualization, and decreased recovery time. 2. Accessory portals, sometimes helpful for visualizing the posterior horns of the menisci and PCL 1. Each knee arthroscopy should include an evaluation of the suprapatellar pouch; patellofemoral joint and tracking; medial and lateral gutters; medial compartment, including the medial meniscus and the articular surface; the lateral compartment, including the lateral meniscus and the articular surface; and the intercondylar notch to visualize the ACL and PCL. 2. The posteromedial corner can be best visualized with a 70-degree arthroscope placed through the notch (modified Gillquist view) or a posteromedial portal.

Sports Medicine

section 1 Knee

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)

Despite intensive research, the function and anatomy of the ACL are still debated.

Despite intensive research, the function and anatomy of the ACL are still debated.

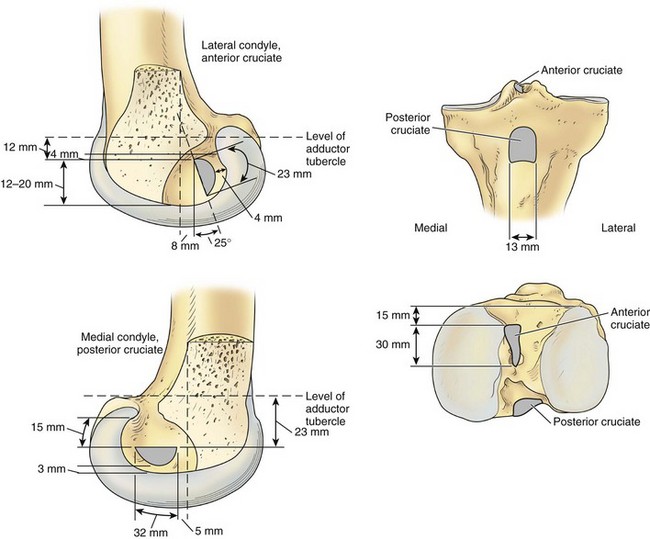

Femoral attachment: semicircular area on the posteromedial aspect of the lateral femoral condyle (Figure 4-1)

Femoral attachment: semicircular area on the posteromedial aspect of the lateral femoral condyle (Figure 4-1)

Tibial insertion: broad, irregular, oval area just anterior to and between the intercondylar eminences of the tibia

Tibial insertion: broad, irregular, oval area just anterior to and between the intercondylar eminences of the tibia

Has two “bundles” named on the basis of tibial insertion:

Has two “bundles” named on the basis of tibial insertion:

Anteromedial: tight in flexion; primarily an anterior restraint; evaluated by Lachman and anterior drawer tests

Anteromedial: tight in flexion; primarily an anterior restraint; evaluated by Lachman and anterior drawer tests

Posterolateral: tight in extension; primarily a rotatory restraint; evaluated by pivot shift test

Posterolateral: tight in extension; primarily a rotatory restraint; evaluated by pivot shift test

Composition: 90% type I collagen and 10% type III collagen

Composition: 90% type I collagen and 10% type III collagen

Blood supply: Both cruciate ligaments receive their blood supply via branches of the middle geniculate artery and the fat pad.

Blood supply: Both cruciate ligaments receive their blood supply via branches of the middle geniculate artery and the fat pad.

Mechanoreceptor nerve fibers within the ACL have been found and may have a proprioceptive role.

Mechanoreceptor nerve fibers within the ACL have been found and may have a proprioceptive role.

Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL)

Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL)

Femoral attachment: broad, crescent-shaped area on the anterolateral medial femoral condyle

Femoral attachment: broad, crescent-shaped area on the anterolateral medial femoral condyle

Tibial insertion: tibial sulcus below articular surface (see Figure 4-1)

Tibial insertion: tibial sulcus below articular surface (see Figure 4-1)

Variable meniscofemoral ligaments originate from the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus and insert into the substance of the PCL.

Variable meniscofemoral ligaments originate from the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus and insert into the substance of the PCL.

Medial collateral ligament (MCL)

Medial collateral ligament (MCL)

Superficial MCL (tibial collateral ligament)

Superficial MCL (tibial collateral ligament)

Lies deep to the gracilis and semitendinosus tendons

Lies deep to the gracilis and semitendinosus tendons

Originates 3.2 mm proximal and 4.8 mm posterior from the medial femoral epicondyle

Originates 3.2 mm proximal and 4.8 mm posterior from the medial femoral epicondyle

Inserts onto the periosteum of the proximal tibia, deep to the pes anserinus

Inserts onto the periosteum of the proximal tibia, deep to the pes anserinus

Superficial fibers insert 61.2 mm distal to the knee joint.

Superficial fibers insert 61.2 mm distal to the knee joint.

Anterior fibers tighten during first 90 degrees of motion; posterior fibers tighten during extension.

Anterior fibers tighten during first 90 degrees of motion; posterior fibers tighten during extension.

Deep portion of the ligament (medial capsular ligament)

Deep portion of the ligament (medial capsular ligament)

Lateral collateral ligament (LCL); also known as the fibular collateral ligament

Lateral collateral ligament (LCL); also known as the fibular collateral ligament

Origin: lateral femoral epicondyle

Origin: lateral femoral epicondyle

Insertion: anterolateral aspect of the fibular head

Insertion: anterolateral aspect of the fibular head

Tight in extension and lax in flexion because of its location behind the axis of knee rotation

Tight in extension and lax in flexion because of its location behind the axis of knee rotation

Deep and posterior to the superficial MCL, contiguous with the deep MCL

Deep and posterior to the superficial MCL, contiguous with the deep MCL

Important factor in rotary stability

Important factor in rotary stability

The posteromedial corner has three components:

The posteromedial corner has three components:

Increasingly important factor in the treatment of the multiple ligament injured knee

Increasingly important factor in the treatment of the multiple ligament injured knee

Originates on the back of the tibia

Originates on the back of the tibia

The femoral insertion is inferior, anterior, and deep to the LCL.

The femoral insertion is inferior, anterior, and deep to the LCL.

Arcuate ligament (which is contiguous with the oblique popliteal ligament medially)

Arcuate ligament (which is contiguous with the oblique popliteal ligament medially)

Fabellofibular ligament (lateral two are really just thickenings of the joint capsule)

Fabellofibular ligament (lateral two are really just thickenings of the joint capsule)

The PLC is the primary stabilizer of external tibial rotation.

The PLC is the primary stabilizer of external tibial rotation.

Layer

Components

I

Sartorius and fascia

II

Superficial MCL, posterior oblique ligament, semimembranosus

III

Deep MCL, capsule

Layer

Components

I

Iliotibial tract, biceps, fascia

II

Patellar retinaculum, patellofemoral ligament

III

Arcuate ligament, fabellofibular ligament, capsule, LCL

The order of insertion of structures on the proximal fibula is, from anterior to posterior, the LCL, the popliteofibular ligament, and the biceps femoris.

The order of insertion of structures on the proximal fibula is, from anterior to posterior, the LCL, the popliteofibular ligament, and the biceps femoris.

Crescent-shaped, fibrocartilagenous structures

Crescent-shaped, fibrocartilagenous structures

Composed predominantly of type 1 collagen

Composed predominantly of type 1 collagen

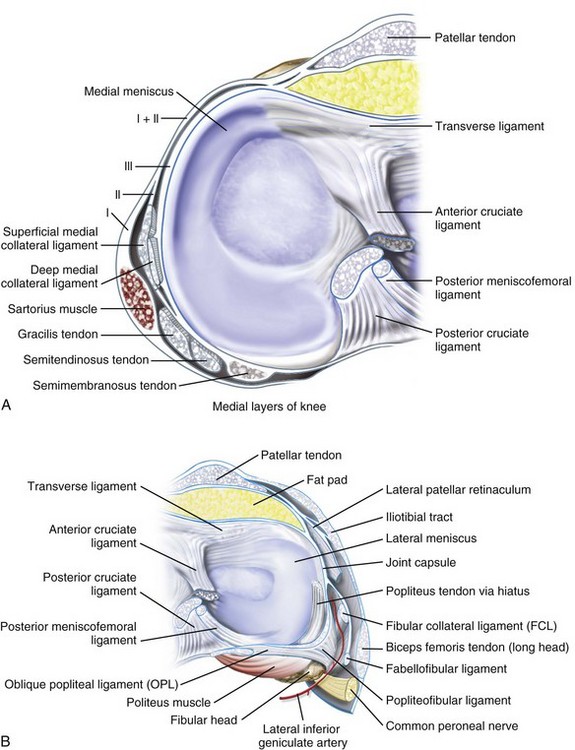

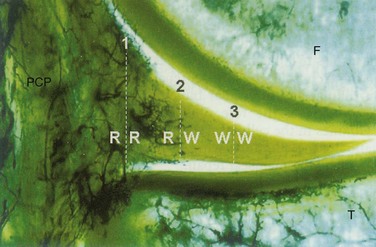

Only the peripheral 20% to 30% of the medial meniscus and the peripheral 10% to 25% of the lateral meniscus are vascularized (medial and lateral genicular arteries, respectively; see Figure 4-1).

Only the peripheral 20% to 30% of the medial meniscus and the peripheral 10% to 25% of the lateral meniscus are vascularized (medial and lateral genicular arteries, respectively; see Figure 4-1).

Medial meniscus is more C-shaped; lateral meniscus is more circular (see Figure 4-1).

Medial meniscus is more C-shaped; lateral meniscus is more circular (see Figure 4-1).

Role: to deepen the articular surfaces of the tibial plateau and function in stability, lubrication, and joint nutrition

Role: to deepen the articular surfaces of the tibial plateau and function in stability, lubrication, and joint nutrition

The two menisci are connected anteriorly by the transverse (intermeniscal) ligament.

The two menisci are connected anteriorly by the transverse (intermeniscal) ligament.

They are attached peripherally by coronary ligaments.

They are attached peripherally by coronary ligaments.

The menisci move anteriorly in extension and posteriorly with flexion. The lateral meniscus has fewer soft tissue attachments and is more mobile than the medial meniscus.

The menisci move anteriorly in extension and posteriorly with flexion. The lateral meniscus has fewer soft tissue attachments and is more mobile than the medial meniscus.

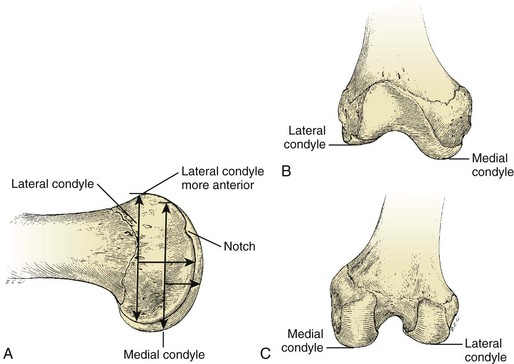

Greater anteroposterior dimensions than medial condyle

Greater anteroposterior dimensions than medial condyle

Relatively straight in comparison with medial condyle

Relatively straight in comparison with medial condyle

Has a terminal sulcus and a groove of the popliteus insertion (Figure 4-3)

Has a terminal sulcus and a groove of the popliteus insertion (Figure 4-3)

Articulation between the patella and femoral trochlea

Articulation between the patella and femoral trochlea

Patella has variably sized medial and lateral facets.

Patella has variably sized medial and lateral facets.

Articular surface of the patella is the thickest in the body.

Articular surface of the patella is the thickest in the body.

The patella can withstand forces several times those of body weight.

The patella can withstand forces several times those of body weight.

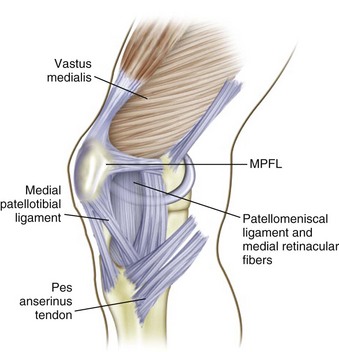

The patella is restrained in trochlea by the valgus axis of the quadriceps mechanism (Q angle), the oblique fibers of the vastus medialis oblique and lateralis muscles (and their extensions, all of which constitute the patella retinaculum), the bony and cartilaginous anatomy of the trochlea, and the patellofemoral ligaments.

The patella is restrained in trochlea by the valgus axis of the quadriceps mechanism (Q angle), the oblique fibers of the vastus medialis oblique and lateralis muscles (and their extensions, all of which constitute the patella retinaculum), the bony and cartilaginous anatomy of the trochlea, and the patellofemoral ligaments.

The medial patellofemoral ligament is present in the second medial layer (Figure 4-4).

The medial patellofemoral ligament is present in the second medial layer (Figure 4-4).

Origin: just anterior and distal to the adductor tubercle or just superior to the origin of the superficial medial collateral ligament

Origin: just anterior and distal to the adductor tubercle or just superior to the origin of the superficial medial collateral ligament

Insertion: junction of proximal and middle third on the medial border of the patella as well as the undersurface of the vastus medialis oblique muscle

Insertion: junction of proximal and middle third on the medial border of the patella as well as the undersurface of the vastus medialis oblique muscle

Role: to prevent lateral displacement of the patella, contributing more than 50% of the total medial restraint to lateral subluxation

Role: to prevent lateral displacement of the patella, contributing more than 50% of the total medial restraint to lateral subluxation

Ligament

Restraint

ACL

Minimizing anterior translation of the tibia in relation to the femur (85%)

PCL

Minimizing posterior tibial displacement (95%)

MCL

Minimizing valgus angulation

LCL

Minimizing varus angulation

MCL and LCL

Acting in concert with posterior structures to control axial rotation of the tibia on the femur

PCL and posterolateral corner

Acting synergistically to resist posterior translation and posterolateral rotary instability

ACL: approximately 2200 N and up to 2500 N in young individuals

ACL: approximately 2200 N and up to 2500 N in young individuals

The tensile strength of a 10-mm patellar tendon graft (young specimen) is more than 2900 N and is about 30% stronger when it is rotated 90 degrees. However, this strength quickly diminishes in vivo.

The tensile strength of a 10-mm patellar tendon graft (young specimen) is more than 2900 N and is about 30% stronger when it is rotated 90 degrees. However, this strength quickly diminishes in vivo.

Studies suggest that the quadrupled hamstring graft has even greater tensile strength but is dependent on graft fixation.

Studies suggest that the quadrupled hamstring graft has even greater tensile strength but is dependent on graft fixation.

PCL: approximately 2500 to 3000 N, but this has been disputed

PCL: approximately 2500 to 3000 N, but this has been disputed

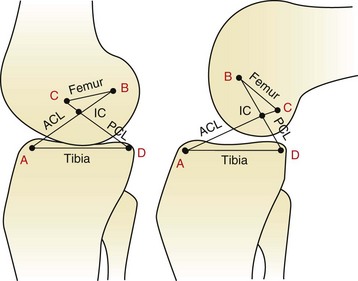

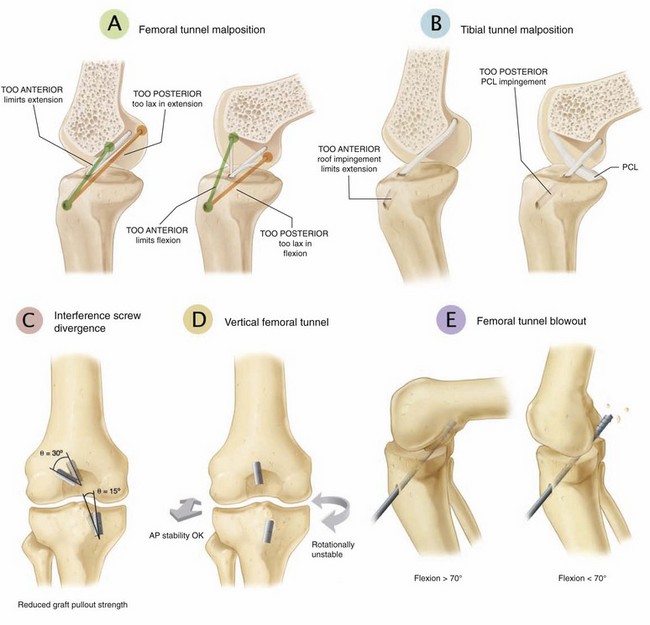

As the knee flexes, the center of joint rotation (intersection of the cruciate ligaments) moves posteriorly, causing rolling and gliding at the articulating surfaces.

As the knee flexes, the center of joint rotation (intersection of the cruciate ligaments) moves posteriorly, causing rolling and gliding at the articulating surfaces.

The concept of ligament “isometry” remains controversial.

The concept of ligament “isometry” remains controversial.

Reconstructed ligaments should approximate normal anatomy and lie within the flexion axis in all positions of knee motion.

Reconstructed ligaments should approximate normal anatomy and lie within the flexion axis in all positions of knee motion.

As the joint flexes, ligaments anterior to the flexion axis stretch, and ligaments posterior to the axis shorten.

As the joint flexes, ligaments anterior to the flexion axis stretch, and ligaments posterior to the axis shorten.

Although many instruments have been designed to achieve isometry, other considerations, such as graft impingement and avoiding flexion contractures, may be of more importance for ligament reconstructions.

Although many instruments have been designed to achieve isometry, other considerations, such as graft impingement and avoiding flexion contractures, may be of more importance for ligament reconstructions.

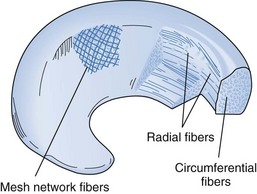

The collagen fibers of the menisci are arranged radially and longitudinally (Figure 4-6).

The collagen fibers of the menisci are arranged radially and longitudinally (Figure 4-6).

The longitudinal fibers help dissipate the hoop stresses in the menisci.

The longitudinal fibers help dissipate the hoop stresses in the menisci.

The combination of fibers allows the meniscus to expand under compressive forces and increase the contact area of the joint.

The combination of fibers allows the meniscus to expand under compressive forces and increase the contact area of the joint.

The lateral meniscus has twice the excursion of the medial meniscus during range of motion (ROM) and rotation of the knee.

The lateral meniscus has twice the excursion of the medial meniscus during range of motion (ROM) and rotation of the knee.

Studies have shown that an ACL deficiency may result in abnormal meniscal strain, particularly in the posterior horn of the medial meniscus (Figure 4-7).

Studies have shown that an ACL deficiency may result in abnormal meniscal strain, particularly in the posterior horn of the medial meniscus (Figure 4-7).

Mensical root tears completely disrupt the circumferential fibers of the meniscus, leading to meniscal extrusion.

Mensical root tears completely disrupt the circumferential fibers of the meniscus, leading to meniscal extrusion.

Biomechanical studies have shown similar load patterns between posterior root tear and complete meniscectomy.

Biomechanical studies have shown similar load patterns between posterior root tear and complete meniscectomy.

![]()

History

Significance

Pain after sitting or climbing stairs

Patellofemoral cause

Locking or pain with squatting

Meniscal tear

Noncontact injury with “popping” sound/sensation

ACL tear, patellar dislocation

Contact injury with “popping” sound

Collateral ligament tear, meniscal tear, fracture

Acute swelling

ACL tear, peripheral meniscal tear, osteochondral fracture, capsule tear

Knee “gives way”

Ligamentous laxity, patellar instability

Anterior force: dorsiflexed foot

Patellar injury

Anterior force: plantar-flexed foot

PCL injury

Dashboard injury

PCL or patellar injury

Hyperextension, varus angulation, and tibial external rotation

Posterolateral corner injury

![]()

Most common causes of an acute hemarthrosis: ACL tear (70%), patella dislocation, osteochondral fracture, and isolated meniscal tear

Most common causes of an acute hemarthrosis: ACL tear (70%), patella dislocation, osteochondral fracture, and isolated meniscal tear

ACL laxity is measured with the knee in slight flexion (20 to 30 degrees) with the application of a standard force (30 pounds [13.6 kg]).

ACL laxity is measured with the knee in slight flexion (20 to 30 degrees) with the application of a standard force (30 pounds [13.6 kg]).

Values are reported as millimeters of anterior displacement, with comparisons with the opposite (normal) side.

Values are reported as millimeters of anterior displacement, with comparisons with the opposite (normal) side.

A difference of more than 3 mm between sides is considered significant.

A difference of more than 3 mm between sides is considered significant.

PCL laxity can also be measured with this device, although it is less accurate.

PCL laxity can also be measured with this device, although it is less accurate.

Weight-bearing 45-degree posteroanterior view

Weight-bearing 45-degree posteroanterior view

Merchant or Laurin view of the patella

Merchant or Laurin view of the patella

Additional views include long-cassette, lower extremity hip-to-ankle views; oblique views; stress radiographs.

Additional views include long-cassette, lower extremity hip-to-ankle views; oblique views; stress radiographs.

Several findings and their significance are listed in Table 4-6.

Several findings and their significance are listed in Table 4-6.

![]()

View/Sign

Findings

Significance

Lateral-high patella

Patella alta

Patellofemoral pathologic process

Congruence angle

µ = −6 degrees; SD = 11 degrees

Patellofemoral pathologic process

Tooth sign

Irregular anterior patella

Patellofemoral chondrosis

Varus/valgus stress view

Opening

Collateral ligament injury; Salter-Harris fracture

Lateral capsule (Segond) sign

Small tibial avulsion off lateral tibia

ACL tear

Pellegrini-Stieda lesion

Avulsion of medial femoral condyle

Chronic MCL injury

Lateral-stress view: stress to anterior tibia with knee flexed 70 degrees

Asymmetric posterior tibial displacement

PCL injury

Weight-bearing posteroanterior view flexion

Early DJD, OCD, notch evaluation

Fairbank changes

Square condyle, peak eminences, ridging, narrowing

Early DJD (postmeniscectomy)

Square lateral condyle

Thickened joint space

Discoid meniscus

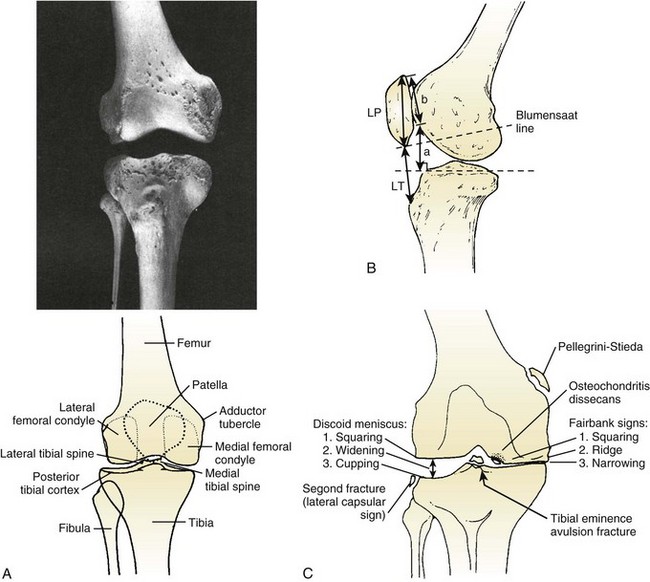

Normal bony anatomy is demonstrated in Figure 4-8, A. Many of these findings are illustrated in Figure 4-8, B.

Normal bony anatomy is demonstrated in Figure 4-8, A. Many of these findings are illustrated in Figure 4-8, B.

Evaluation of patella height is accomplished by one of three commonly used methods (see Figure 4-8, C).

Evaluation of patella height is accomplished by one of three commonly used methods (see Figure 4-8, C).

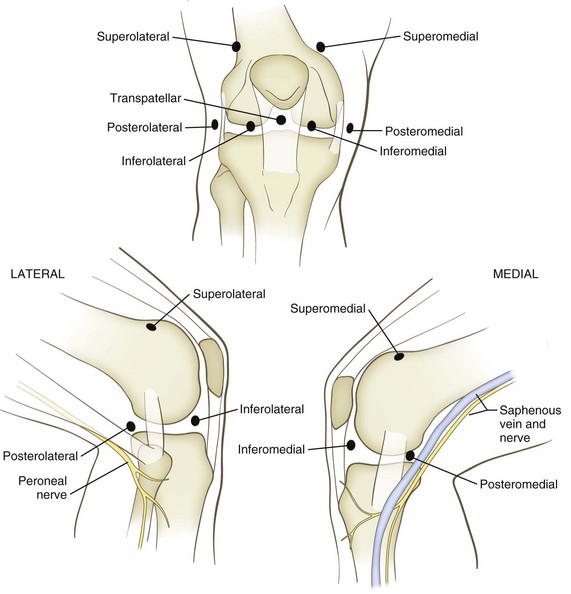

Posteromedial portal: 1 cm above the joint line behind the MCL (be careful to avoid saphenous nerve branches)

Posteromedial portal: 1 cm above the joint line behind the MCL (be careful to avoid saphenous nerve branches)

Posterolateral portal: 1 cm above the joint line between the LCL and biceps tendon (avoiding the common peroneal nerve)

Posterolateral portal: 1 cm above the joint line between the LCL and biceps tendon (avoiding the common peroneal nerve)

Transpatellar portal: 1 cm distal to the patella, splitting the patellar tendon fibers; can be used for central viewing or grabbing but should be avoided in patients who require subsequent harvesting of autogenous patellar tendon

Transpatellar portal: 1 cm distal to the patella, splitting the patellar tendon fibers; can be used for central viewing or grabbing but should be avoided in patients who require subsequent harvesting of autogenous patellar tendon

Meniscal tears are the most common injury to the knee that necessitates surgery.

Meniscal tears are the most common injury to the knee that necessitates surgery.

The medial meniscus is torn approximately three times more often than the lateral meniscus.

The medial meniscus is torn approximately three times more often than the lateral meniscus.

There is an increased rate of osteoarthritis in knees after both meniscal tears and meniscectomy.

There is an increased rate of osteoarthritis in knees after both meniscal tears and meniscectomy.

Traumatic meniscal tears are common in young patients with sports-related injuries.

Traumatic meniscal tears are common in young patients with sports-related injuries.

Degenerative tears usually occur in older patients and can have an insidious onset.

Degenerative tears usually occur in older patients and can have an insidious onset.

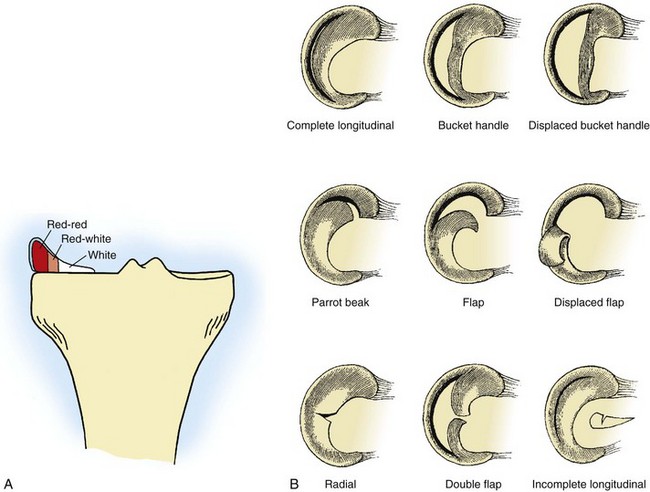

Meniscal tears can be classified according to their location in relation to the vascular supply, their position (anterior, middle, or posterior third), and their appearance and orientation (Figure 4-10).

Meniscal tears can be classified according to their location in relation to the vascular supply, their position (anterior, middle, or posterior third), and their appearance and orientation (Figure 4-10).

Meniscal root tears completely disrupt the circumferential fibers of the meniscus and can lead to meniscal extrusion.

Meniscal root tears completely disrupt the circumferential fibers of the meniscus and can lead to meniscal extrusion.

The vascular supply of the meniscus is a primary determinant of healing potential.

The vascular supply of the meniscus is a primary determinant of healing potential.

In the absence of intermittent swelling, catching, locking, or giving way, meniscal tears—particularly those degenerative in nature—may be treated conservatively.

In the absence of intermittent swelling, catching, locking, or giving way, meniscal tears—particularly those degenerative in nature—may be treated conservatively.

Younger patients with acute tears, patients with tears causing mechanical symptoms, and patients with tears that fail to improve with conservative measures may benefit from operative treatment.

Younger patients with acute tears, patients with tears causing mechanical symptoms, and patients with tears that fail to improve with conservative measures may benefit from operative treatment.

Tears that are not amenable to repair (e.g., peripheral, longitudinal tears)—excluding those that do not necessitate any treatment (e.g., partial-thickness tears, those <5 to 10 mm in length, and those that cannot be displaced >1 to 2 mm)—are best treated by partial meniscectomy.

Tears that are not amenable to repair (e.g., peripheral, longitudinal tears)—excluding those that do not necessitate any treatment (e.g., partial-thickness tears, those <5 to 10 mm in length, and those that cannot be displaced >1 to 2 mm)—are best treated by partial meniscectomy.

In general, complex, degenerative, and central/radial tears are treated with resection of a minimal amount of normal meniscus. A motorized shaver is helpful for creating a smooth transition zone.

In general, complex, degenerative, and central/radial tears are treated with resection of a minimal amount of normal meniscus. A motorized shaver is helpful for creating a smooth transition zone.

The role of lasers or other devices for this purpose is still under investigation. There is concern about possible iatrogenic chondral injury caused by lasers and other thermal devices.

The role of lasers or other devices for this purpose is still under investigation. There is concern about possible iatrogenic chondral injury caused by lasers and other thermal devices.

Should be done for all peripheral longitudinal tears, especially in young patients and in conjunction with an ACL reconstruction

Should be done for all peripheral longitudinal tears, especially in young patients and in conjunction with an ACL reconstruction

Augmentation techniques (fibrin clot, vascular access channels, synovial rasping) may extend the indications for repair.

Augmentation techniques (fibrin clot, vascular access channels, synovial rasping) may extend the indications for repair.

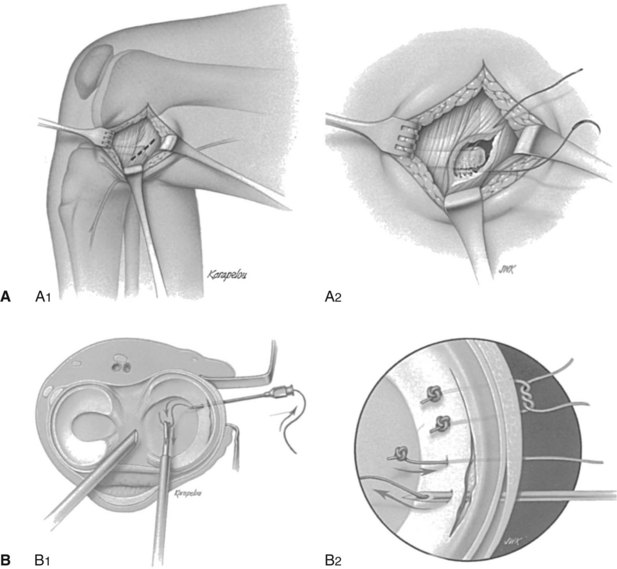

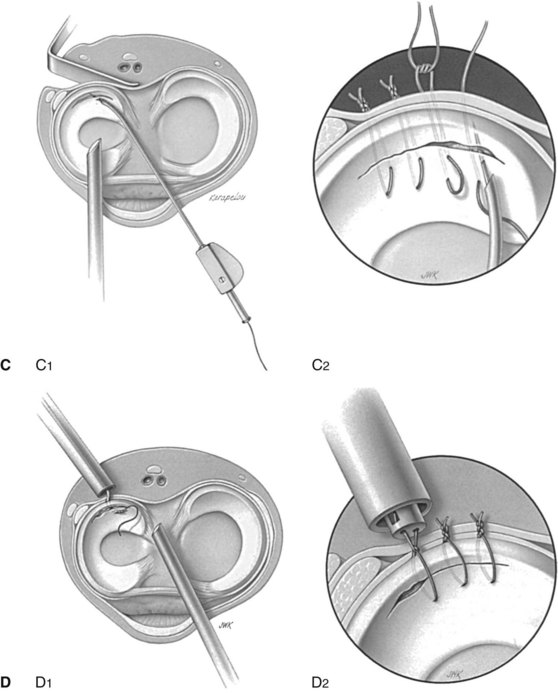

Four techniques are commonly used: open, “outside-in,” “inside-out,” and “all-inside” (Figure 4-12).

Four techniques are commonly used: open, “outside-in,” “inside-out,” and “all-inside” (Figure 4-12).

Newer techniques for all-inside repairs (e.g., arrows, darts, staples, screws) are popular because of their ease of use; however, they are probably not as reliable as vertical mattress sutures.

Newer techniques for all-inside repairs (e.g., arrows, darts, staples, screws) are popular because of their ease of use; however, they are probably not as reliable as vertical mattress sutures.

The latest generation of “all-inside” devices allows tensioning of the construct.

The latest generation of “all-inside” devices allows tensioning of the construct.

The “gold standard” for meniscal repair remains the inside-out technique with vertical mattress sutures.

The “gold standard” for meniscal repair remains the inside-out technique with vertical mattress sutures.

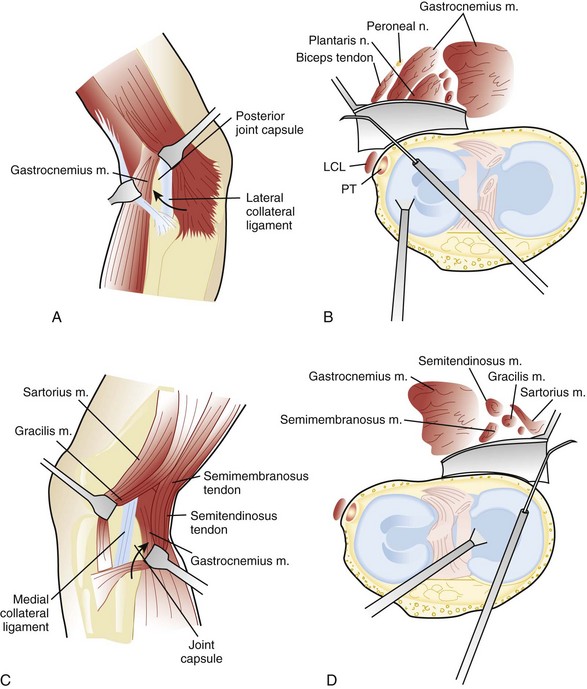

Regardless of the technique used, it is essential to protect the saphenous nerve branches (anterior to both the semitendinosis and gracilis muscles and posterior to the inferior border of the sartorius muscle) during medial repairs and to protect the peroneal nerve (posterior to the biceps femoris) during lateral repairs (Figure 4-13).

Regardless of the technique used, it is essential to protect the saphenous nerve branches (anterior to both the semitendinosis and gracilis muscles and posterior to the inferior border of the sartorius muscle) during medial repairs and to protect the peroneal nerve (posterior to the biceps femoris) during lateral repairs (Figure 4-13).

In several studies, 80% to 90% success rates with meniscal repairs have been reported. However, success depends on location, type of tear, and chronicity.

In several studies, 80% to 90% success rates with meniscal repairs have been reported. However, success depends on location, type of tear, and chronicity.

It is generally accepted that the results of meniscal repair are best with acute peripheral tears in young patients with concurrent ACL reconstruction.

It is generally accepted that the results of meniscal repair are best with acute peripheral tears in young patients with concurrent ACL reconstruction.

In general, success rates are 90% when meniscal repair is performed in conjunction with an ACL reconstruction, 60% with a repair in which the ACL is intact, and 30% with a repair in which the ACL is deficient.

In general, success rates are 90% when meniscal repair is performed in conjunction with an ACL reconstruction, 60% with a repair in which the ACL is intact, and 30% with a repair in which the ACL is deficient.