Chapter 16 Spinal Cord Injuries

Acute spinal cord injuries

Introduction

• A spinal cord injury (SCI) is a traumatic event for both the patient and their family and it provides a multifactorial challenge to health care staff.

• It is fortunately a relatively rare presentation, with approximately 800–1000 new cases per year and an estimated 40 000 people living with an SCI in the UK (Kennedy 1998, Nichols et al 2005, Harrison 2007).

• When compared to other neurological disorders, such as a cerebrovascular accident (CVA) – 150 000 cases/year in the UK (Carroll et al 2001), the chances of a student or Band 5 physiotherapist encountering a SCI patient outside of a specialist centre is slim.

• However, it is this unfamiliarity with the presentation that can be particularly daunting to a physiotherapist of any grade.

• Most new cases of SCI first present to a district general hospital via accident and emergency.

• The National Service Framework for Long Term Conditions (Department of Health 2005) suggests a minimum standard of up to 24 hours of diagnosis and transfer within the first 48 hours; admission to a specialist centre is likely to be delayed by concerns around medical stability and bed availability (Harrison 2007).

• Patients with an established injury are also likely to be admitted to their local hospital during periods of acute deterioration or other periods of illness.

• Some patients with dual diagnoses, e.g. SCI and a traumatic brain injury may never reach an SCI centre.

• This can also be the case with some patients that have non-traumatic spinal cord impairments.

• As such, the initial management will invariably be provided by a therapist with a generalised experience or no previous experience of working with patients that have incurred a spinal cord injury.

• In addition to the management required during the acute phase, immediately post injury, the patient will require longer-term rehabilitation.

• If the patient has been managed in a SCI centre during the acute phase they will require their care to be transferred to a hospital/service closer to their home, for management of their progression or maintenance of their presentation.

• This may include physiotherapy rehabilitation.

• With the muscle imbalance and overuse characteristics inherent in SCI, complaints of a musculoskeletal nature are also common (Bromley 2006).

• Thus, a physiotherapist is likely to be required to manage the care of a SCI patient in a number of different circumstances at some time in their career, regardless of their background being respiratory, neurological or musculoskeletal.

• It is therefore in a therapist’s interest to develop a basic understanding of the presentation and needs of this patient population, and more importantly, a knowledge of where to seek and access assistance in the sometimes complex and challenging care that these patients need to receive.

• Therapists encountering patients with SCI for the first time can feel concerned that they do not have the appropriate clinical skills or knowledge to effectively manage this patient group.

• However it is important to stress at this point that a therapist should not consider that they are managing a patient in isolation.

• Specific advice should always be sought from SCI centres to ensure the patient is being managed in the best possible way and this will ensure that the therapist develops their experience, expertise and confidence in an appropriate way.

• Most SCI centres aim to provide acute outreach teams, either in person and/or via phone to advise, educate and support peer professionals.

• This service has been shown to improve referral times and reduce the incidence or severity of preventable complications prior to a patient’s transfer (Harrison 2001, 2007).

• It cannot be emphasised enough that the information included in this book does not propose to replace the specific individualised advice that can be obtained from contacting specialists in the field of SCI management based in the 11 SCI centres in the UK (Appendix 16.1).

• However, the assessment of a patient with a spinal cord injury follows a fundamental construct, using the skills of assessment that are common to all physiotherapists, and the information obtained will provide the basis of the patient’s planned management.

• The aim of this text is to demonstrate to a therapist new to the field that they already have many skills to assess and manage this presentation and with some background knowledge and slight adjustment to the delivery, a competent and effective delivery of care is achievable for an otherwise challenging presentation.

General considerations during the assessment of acute SCI

• A spinal cord injury is considered to be one of the most devastating conditions that can occur following a trauma.

• In seconds an individual is catapulted from a familiar life as an able-bodied person into a previously unknown situation and an environment of, in most cases, permanent disability.

Mechanism and demographics

• The most common mechanism for a traumatic SCI is a sudden impact or deceleration whereby the forces are transmitted through the spinal column. Velocity is not related to the existence of injury, but will affect the extent of injury if one is to occur (Ravichandran 1990).

• Road traffic accidents, falls and injuries from participating in sport are the most common causes of SCI.

• Incidence of SCI in the British Isles is outlined in Table 16.1.

• Up to 50% of injuries from a motor vehicle collision will also present with multi-trauma, including multiple level spinal injury, limb fracture, abdominal, chest, facial or head injury or significant soft tissue trauma (Prasad et al 1999).

• Non-traumatic causes, e.g. neoplasm, infarct, infection, have been estimated at being 20% of the total prevalence (Harrison 2007).

• In a 5-year prospective study of the Irish National Spinal Unit between 1999 and 2003, Lenehan et al (2009) reported 73% of admissions were male, with an average age of 32 years.

• The majority were injuries to the cervical spine (51%), followed by lumbar (28%) and thoracic (21%).

• One third had a complete spinal injury on admission.

• Previously, the condition was predominantly seen in young men, but as the population ages and remains more active, there has been a discernable increase in the number of older people with SCI (Nichols et al 2005).

• Paralysis most frequently occurs in traumatic SCI when instability and damage to the spinal column leads to disruption of the spinal cord.

• ‘Severance’ or ‘cutting’ of the spinal cord rarely occurs outside of stabbing or gunshot injuries.

• More commonly, compression of the spinal cord resulting in ischaemic necrosis and swelling, leads to the formation of the impairment (Harrison 2007).

• It is thus difficult to predict the finality of the impairment, as the oedema and spinal shock can progress or resolve over time, with subsequent changes in neurological impairment (Ravichandran 1990).

Table 16.1 Causes of SCI in the United Kingdom & Ireland (O’Connor and Murray 2006)

| Cause of injury | Number of SCI centre admissions |

|---|---|

| Fall | 24 |

| Motor vehicle collision | 23 |

| Sport/recreation | 4 |

| Knocked over (e.g. falling object) | 1 |

| Other | 1 |

Initial management

• The spinal cord injured patient will present with a wide range of impairments that may include all of the body systems.

• Patients with an acute SCI will need specific management to stabilise the injury site and maintain the function of the vital systems of the body to prevent complications from occurring.

• Upon arrival to A&E, assessment of the person with suspected spinal cord injury will commence immediately by the medical team.

• Once vital signs and life-threatening concerns are dealt with, the doctor will assess the injury, looking for obvious signs of spinal injury, such as spinal deformity and pain on palpation, loss or altered power or sensation and bladder and bowel disturbance (Harrison 2007).

• There will typically follow a request for a spinal X-ray, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the affected area to determine stability of the fracture and the extent of spinal cord damage.

• Clinically, this will be paralleled with a test to determine neurological level and the degree of completeness.

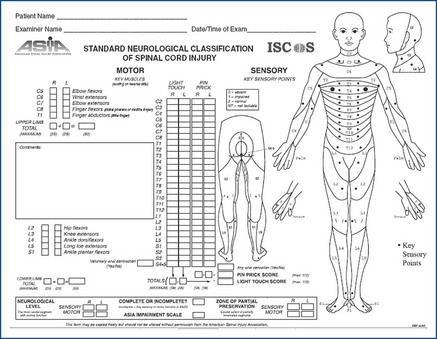

• The American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) developed a classification which has been adopted internationally, to assess and monitor the spinal cord injury (Figure 16.1).

• The motor assessment assesses 10 key muscles bilaterally (5 in the upper limb, 5 in the lower limb) whilst the sensory assessment assesses each dermatome bilaterally using standardised anatomical landmarks for light touch and pin prick sensation.

• Combined together this information determines the neurological level of injury, the completeness of injury and the syndrome (if an incomplete injury is diagnosed).

• The ‘neurological level’ is defined as ‘the lowest segment where motor and sensory function is normal on both sides’ (ASIA 2001) or in other words, the last level of normal neurological function.

• This does not always correspond to the level of vertebral injury.

• The higher the injury level, the greater the number of bodily functions that will be adversely affected.

• Patients with incomplete spinal cord injuries may experience more pain and muscle imbalance than a patient with a complete lesion at the same level.

• The neurological level may change over time as the swelling or bleeding within the spinal cord develops.

• Should the level ascend, it will be an important indicator of the potential progression of a disease or the onset of a complication.

• This can occur in both acutely injured and established patients.

• Thus subjective reporting and clinical monitoring are vitally important in identifying the frequency with which the assessment monitoring should be carried out.

Figure 16.1 Standards for Neurological Classification of SCI Worksheet (Dermatomes Chart).

American Spinal Injury Association, 2011. International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury, revised April, 2011. American Spinal Injury Association, Chicago, IL. http://www.asia-spinalinjury.org/.

Definitions of complete and incomplete SCI

• Confusion often exists around the classification of complete versus incomplete injury.

• The ASIA Impairment Scale (AIS) provides a framework within which a categorisation can be provided.

• The scale is divided into five groups, A–E.

• Each of these is outlined on the reverse side of the standardised worksheet (Box 16.1).

• In the acute phase the exact extent of the completeness of the lesion may not be clearly defined due to the presence of swelling surrounding the spinal cord.

Box 16.1

Categorisation of SCI

No motor or sensory function is preserved in the sacral segments S4 to S5

Sensory but not motor function is preserved below the neurological level and includes the sacral segments S4 to S5

Motor function is preserved below the neurological level and more than half of the key muscles below the neurological level have a muscle grade less than 3

Motor function is preserved below the neurological level and at least half the key muscles below the neurological level have a muscle grade of 3 or more

American Spinal Injury Association: International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury, revised 2011: Atlanta, GA. Reprinted 2011.

Incomplete lesion

• This includes AIS grades B–D.

• Sacral function at S4/5 must be preserved.

• The classification ASIA E is used for those who have normal motor function within the key muscles and normal sensory function.

• The motor and sensory scoring, however, may not be sensitive enough to identify the presence of spasticity or pain, subtle weakness, core instability or certain forms of dysaesthesia that could be a result of a spinal cord injury.

• Therefore those who are categorised AIS E may still require rehabilitation to address these issues.

Spinal shock

• Following a SCI, there will be a sudden and transient suppression of both somatomotor reflexes and autonomic function below the injury.

• This ‘spinal areflexia’ will result in flaccid paralysis of trunk and limbs and loss of vasomotor function with resultant hypotension.

• Urinary retention and constipation ensue due to bladder and bowel stasis (known as ‘paralytic ileus’) and male patients may experience sustained priapism (Nichols et al 2005).

• Perhaps the most worrying component for the physiotherapist is the loss of sympathetic outflow to the heart in injuries above T3, resulting in bradycardia or sinus arrest during turns, and suctioning. However, this is preventable.

• The period of spinal shock can last up to 6 weeks, but can be delayed by post injury complications (Benevento and Sipski 2002).

• Resolution of certain reflexes occurs at different rates, with Babinski’s sign returning within the first day and bladder tone requiring up to 3 months (Ditunno et al 2004).

Autonomic dysreflexia

• This is a potentially fatal consequence of an injury above T6.

• It is the body’s exaggerated reaction to a noxious stimulus below the neurological level, resulting in a rapid and extreme increase in blood pressure, which, if untreated, could cause cerebral haemorrhage.

• It manifests with a pounding headache, sweating and blotching of the skin above the lesion, pallor below the lesion, and bradycardia (Nichols et al 2005).

• The stimulus is usually a blocked catheter, constipation, sharp object, labour or passive movements.

• Treatment includes removing the stimulus, sitting the patient upright and using antihypertensive medication, e.g. nitrolingual spray.

Heterotrophic ossification

• Abnormal calcification at areas of small muscle tears is a suggested aetiology of this presentation, whereby bone is deposited around joints, especially the hip and knees.

• However the pathophysiology is still a matter for conjecture.

• The first signs are a ‘spongy’ end feel, with mild oedema and erythema.

• X-rays are normal for the first 2–3 weeks, then show ‘cloudy patches’ in affected areas (Bromley 2006).

• Ultrasonography is the preferred diagnostic tool in early stages and epidronate is the medication of choice.

• Passive movements are discontinued initially for approximately 1 week. Frequency, repetition and force of passive movements are progressed cautiously over the ensuing 4–8 weeks (Bromley 2006).

• Surgery is only considered in cases of hindered function and/or sitting posture, however recurrence of ossification at the surgical site is common.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree