Chapter 18 Special Topics

Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy

Reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD), now commonly referred to as complex regional pain syndrome 1 (CRPS), is a common disorder of unknown cause that often follows a relatively minor injury. It has been called by several names: Sudeck’s atrophy, causalgia, shoulder–hand syndrome, posttraumatic dystrophy, and others. The pathogenesis of the disorder is unclear, but a disturbance in the sympathetic nervous system apparently develops that leads to the characteristic symptoms and signs of intense pain (allodynia) and vasomotor disturbances. The condition usually affects the extremity rather than the torso. Early recognition is difficult. CRPS is divided into two types with similar clinical features, but type 2 is associated with more significant nerve injury, including causalgia and traumatic neuralgias.

CLINICAL FEATURES

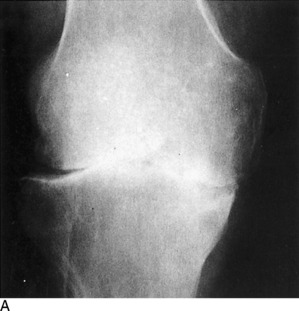

Although no imaging studies are diagnostic, plain roentgenograms may eventually reveal patchy osteoporosis (Fig. 18-1). The bone scan may be positive, showing regional uptake that is diagnostic and reflects increased blood flow.

Rotational Deformities of the Legs in Children

Developmental abnormalities of the lower extremities are common and are frequently a source of concern to parents. The cause of these deformities is unknown, but hereditary and persistent postnatal malpositioning play important roles. Most correct themselves spontaneously.

IN-TOEING

All three of these deformities are aggravated by positions or postures that are frequently assumed by the child or infant. Lying in the prone position with the legs extended and the feet internally rotated is often associated with in-toeing deformity. Sitting in the “reverse-tailor” position with the feet internally rotated beneath the buttocks is directly related to persistent tibial rotation and adduction of the forefoot (Fig. 18-2). Children may assume these positions for extended periods of time while sleeping, playing, or watching television.

INTERNAL FEMORAL TORSION

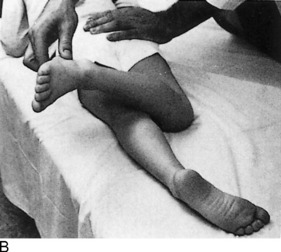

The diagnosis is made by clinical examination. It is helpful to mark the patellae and observe their position as the child walks. If the child toes in and the patellae face medially, excessive femoral anteversion or an internal rotation contracture of the hips should be suspected. If the child toes in and the patellae face straight forward, then the deformity has to be distal to the knee, either internal tibial torsion or metatarsus varus. Internal femoral torsion can also be measured with the patient prone, the hips extended, and the knees flexed 90 degrees (Fig. 18-3). External and internal measurements of hip motion are then made, with the tibia acting as a pointer. An internal rotation deformity exists at the hip when internal rotation exceeds external rotation by more than 30 degrees.

INTERNAL TIBIAL TORSION

An approximate measurement of tibial torsion can be obtained by having the patient sit on the examining table with the knees flexed 90 degrees over the side. The tibial tubercle is palpated and directed straight forward. The malleoli are then grasped with the thumb and index finger, and the position of the axis of the ankle joint is determined (Fig. 18-4). Normally, 20 to 30 degrees of external tibial torsion is present in adults, and the lateral malleolus is slightly posterior to the medial malleolus. In children with internal tibial torsion, the lateral malleolus is anterior to the medial malleolus.

METATARSUS VARUS

With the child in the same sitting position, the foot is examined for deformity. If metatarsus varus is present, the lateral border of the foot is convex, and the medial border is concave (Fig. 18-5).

TREATMENT

Tibial torsion is best treated by observation and reassurance. Spontaneous correction usually occurs with growth. Improper sitting and sleeping habits should be corrected. Stretching exercises are of no value. Corrective shoes appear to be of no benefit in the treatment of any of these problems.

The treatment of metatarsus varus depends on whether the deformity is fixed. If the foot is flexible and the deformity easily overcorrectable, passive stretching exercises and a straight or reverse-last shoe are sometimes tried, although their effectiveness is unknown (Fig. 18-6). If the forefoot is rigid and passive correction of the deformity is not possible, early treatment with corrective casts may be indicated. The correction should begin shortly after birth. When the disorder is seen after the age of 1 or 2 years, operative intervention is occasionally necessary. Early diagnosis is therefore important.

OUT-TOEING

External rotation deformity of the lower extremities is usually caused by the following: (1) external rotation of the hip secondary to soft tissue contracture or femoral retroversion (external femoral torsion), (2) external tibial torsion, or (3) pes calcaneovalgus, or flatfeet. Out-toeing is often associated with a genu valgum deformity and may be aggravated by sleeping in the prone position (Fig. 18-7). The use of wide diapers or a children’s “walker” with a wide pad may potentiate an externally rotated gait.

If femoral retroversion is the cause, examination reveals that external rotation of the hips is significantly greater than internal rotation. External tibial torsion is diagnosed by the marked posterior position of the lateral malleolus compared with the medial. The flatfoot deformity is frequently associated with eversion of the heels (see Chapter 12).

Angular Deformities of the Legs in Children

GENU VARUM (BOWED LEGS)

The child is commonly brought to the doctor because of the wide space between the knees and the mild in-toeing gait. Other possible causes of bowing (such as rickets and Blount’s disease) can generally be ruled out by the child’s history. Roentgenograms may be necessary. There is usually no evidence of any intrinsic bone disease. The amount of genu varum can be determined by measuring the distance between the medial femoral condyles with the child standing and the medial malleoli touching.

BLOUNT’S DISEASE

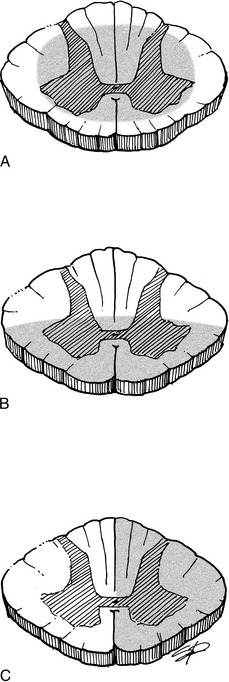

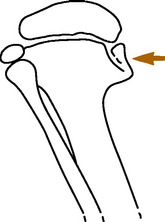

This is an uncommon pathologic, developmental bowing that results from altered growth of the upper medial tibial epiphysis (Fig. 18-8). The cause is unknown, but abnormal pressure may play a role. Blount’s disease is more common in obese early walkers and children of short stature. It is also more common in blacks. It may be unilateral, in contrast to physiologic bowing, which is almost always bilateral. Two forms of Blount’s disease are described: an infantile type, which begins before age 3; and an adolescent form, which starts after age 8. Before the age of 2, the infantile form may be difficult to differentiate from physiologic bowing, especially if it is bilateral. Although physiologic bowing resolves with growth, Blount’s disease progressively worsens. A strong family history and severe bowing are indications for roentgenographic evaluation.

FIG. 18-8 Diagram of Blount’s disease, showing disturbance of the growth of the medial tibial epiphysis.

GENU VALGUM (KNOCK-KNEE)

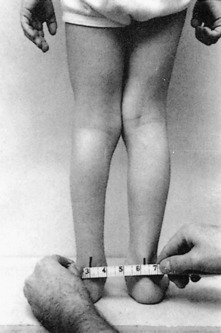

Knock-knee may be caused by a variety of disorders, including injury and metabolic disease. However, most genu valgum is present as one stage in the normal physiologic “swing” between developmental genu varum and normal alignment. It is usually bilateral and is most common between the ages of 2 and 4 years. The severity of the deformity can be determined by measuring between the medial malleoli or Achilles tendons with the child standing, the medial femoral condyles touching, and the patellae facing forward (Fig. 18-9). Similar measurements can be taken on return visits to confirm spontaneous correction if reassurance is needed.

Leg Length Inequality

Limb length discrepancies in the lower extremities may result from several causes. The most common are fractures, osteomyelitis, neuromuscular disease, and vascular anomalies. Usually, the affected limb is shorter, but occasionally the inequality is the result of overgrowth because of epiphyseal stimulation by inflammation or injury. Frequently, no cause is found. The inequality may cause a mild limp and compensatory scoliosis.

Primary Bone Tumors

BENIGN BONE TUMORS

Most common benign bony neoplasms are either fibrous or cartilaginous. Cystic lesions such the simple bone cyst (see Chapter 5) occur with some frequency but may not be true neoplasms. The benign lesions that occur with any frequency are as follows: (1) fibrous cortical defect; (2), nonossifying fibroma; (3) fibrous dysplasia; (4) enchondroma; and (5) osteochondroma. Most of these lesions are diagnosed by a specific clinical and radiographic presentation, often related to the age of the patient and the bone involved. And although the radiographic appearance may not always be pathognomonic in all cases, certain characteristics are highly suggestive of specific lesions. Radiologic or orthopedic referral is valuable to determine the significance of such lesions.

Enchondromas are benign tumors of cartilage usually located centrally in bone. The most common sites are the small bones of the hand and feet (Fig. 18-10). The enchondroma is the most common tumor of the bones of the hand. It most often occurs in patients between the ages of 10 and 50 years. Symptoms are nonspecific. The lesion is usually discovered incidentally or is identified after a pathologic fracture. Treatment is simple observation if the diagnosis is obvious. If enough bone weakness is present, leading to recurrent fracture, or if the diagnosis is uncertain, surgical intervention is indicated.

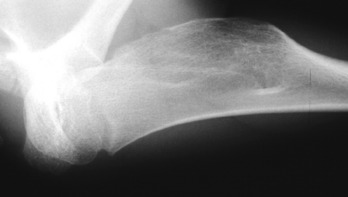

FIG. 18-10 Enchondroma of the phalanx. The lesion is well circumscribed. A pathologic fracture is present.

Osteochondromas are the most common of all benign bone growths. They may not actually be neoplasms but are more likely developmental abnormalities thought to be the result of some “pinching-off” of a portion of growth cartilage. This lesion begins to grow separately, and its growth ceases when the patient reaches skeletal maturity. The typical site of formation is on the metaphysis near the growth plate of the distal femur or proximal tibia, but they can be found on other long bones (Fig. 18-11). Most lesions consist of a stalk that is directed away from the growth plate from which it originated. The lesion is covered with a cartilaginous cap. Signs and symptoms are related to the presence of the mass, but most are only minimally symptomatic. The lesion is removed if producing symptoms. These lesions commonly regress when growth ceases.

Fibrous lesions of bone are common benign neoplasms that are usually discovered incidentally. Fibrous cortical defects are common in growing bone and have a characteristic radiographic appearance (Fig. 18-12). They are asymptomatic and do not require further investigation or treatment. The lesions most likely resolve within 2 to 3 years.

Nonossifying fibromas are similar lesions histologically but are much larger (Fig. 18-13). Biopsy is not usually required, but treatment may be needed in large lesions that are painful. These often regress as well.

Fibrous dysplasia is a developmental disturbance of bone formation in which fibroplastic proliferation occurs. The disorder may be monostotic or polyostotic. Endocrine abnormalities may also be present. Marked deformities may develop over time. The tibia is commonly involved, and pathologic fracture may occur (Fig. 18-14). Referral for surgery is indicated when deformity or pathologic fracture develops.

MALIGNANT BONE TUMORS

Primary malignant bone tumors are invasive, anaplastic, and have the ability to metastasize. Most arise from the marrow (myeloma), but tumors may develop from bone, cartilage, fat, and fibrous tissues. Leukemia and lymphoma are excluded from this discussion. Fibrosarcoma and liposarcoma are extremely rare. They are similar to those tumors arising in soft tissue. Osteosarcoma is an uncommon primary malignant tumor of bone characterized by malignant tumor cells that produce osteoid or bone. Several variants have been described: parosteal sarcoma, periosteal sarcoma, multicentric, and telangiectatic forms. Chondrosarcoma is a malignant cartilage tumor that may develop primarily or secondarily from transformation of a benign osteocartilaginous exostosis or enchondroma. Ewing’s sarcoma is a malignant tumor of unknown histogenesis, and multiple myeloma is a neoplastic proliferation of plasma cells.

EVALUATION

Speckled calcifications in a destructive radiolucent lesion are usually suggestive of chondrosarcoma. Ewing’s sarcoma is characterized radiographically by mottled, irregular destructive changes with periosteal new bone formation. The latter may be multilayered, producing the typical “onion skin” appearance.

The typical roentgenographic finding in multiple myeloma is the “punched-out” lesion with sharply demarcated edges (Fig. 18-15). Other characteristics include the following: (1) multiple lesions are usual; (2) diffuse osteoporosis may be the only finding in many cases; and (3) pathologic fractures are common.

Spinal Cord Compression

CLINICAL FEATURES

Clinical findings reflect the amount of spinal cord involvement (Fig. 18-16): there are usually motor loss and sensory abnormalities. Babinski testing is usually positive, and clonus is commonly present. Gradual compression is often manifested by progressive difficulty walking, clonus with weight bearing, and involuntary spasm; development of sensory symptoms; bladder dysfunction is a late finding. The following list describes findings in various types of spinal cord syndromes:

ETIOLOGY

Among the most common causes of spinal cord syndromes are trauma, tumor, infection, and degenerative disc conditions with spinal stenosis. Sometimes the central cord syndrome develops from compression of the cord from the front by a bulging or degenerative disc and from the back by a buckled ligamentum flavum. The stenotic spine may be more susceptible. Other causes of cord compression are inflammatory processes, cystic abnormalities, and severe disc herniation.

Spinal Braces

CERVICAL COLLARS

Cervical collars extend from the head to the thorax and are usually soft, although semirigid collars are also available (Fig. 18-17). The soft collar is usually more comfortable but restricts motion less than the other collars. These appliances are all used in the treatment of degenerative disc disease and minor ligamentous or muscular injuries of the cervical spine.

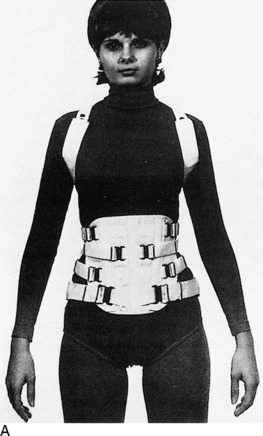

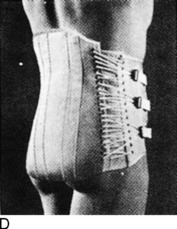

TAYLOR BRACE

This is a fundamental back brace useful in dorsal and lumbar spine disease (Fig 18-18). It is a high, semirigid brace that may be modified. Degenerative disc disease and minor fractures may be treated with this brace or one of its modifications (long Taylor, modified Taylor, and short Taylor).

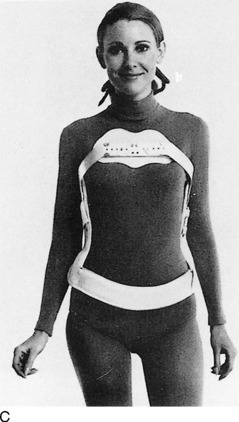

JEWETT (HYPEREXTENSION) BRACE

This three-point brace provides pressure over the lumbar spine, sternum, and symphysis pubis. It is used in minor fractures of the dorsal spine when extension is desired. It is also useful in the treatment of epiphysitis.

Disability Rating

Physical impairment can usually be measured accurately on the basis of the loss of physical function. A careful clinical history and physical examination are mandatory. Laboratory and roentgenographic analysis may also be necessary.

Joint Replacement Surgery

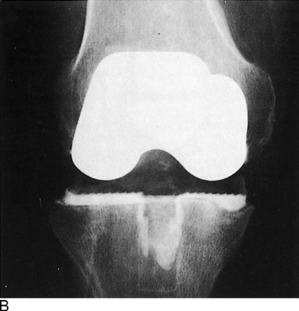

Great advances have been made in the past 25 years in the surgical treatment of degenerative and rheumatoid arthritis. These advances have been primarily caused by improvements in the techniques of joint arthroplasty. This procedure is most commonly used for conditions of the hip and knee, but devices have been developed for use in almost every joint (Fig. 18-19). The indications for surgery are the presence of arthritis and failed medical management.

The basic purpose of these techniques is to implant a device into the joint that replaces the degenerated articular surfaces. Most joint replacement procedures use a hard plastic, high-density polyethylene for the socket (Fig. 18-20). This articulates with a metallic component, both components usually being fixed to the bone by a cementing compound, methylmethacrylate, or by an in-growth system.

FIG. 18-20 A, Degenerative arthritis of the knee. B, Postoperative roentgenogram after total knee replacement.

Mechanical problems with total knee replacement are slightly more common than those after total hip replacement, but the results are uniformly good in both procedures. More than 90% of patients undergoing arthroplasty have excellent relief of pain and improvement in motion. Short-term problems are those related to infection and venous thrombosis, both of which are treated prophylactically. Long-term concerns include aseptic loosening and osteolysis, a term used to describe an inflammatory response to particulate debris that can lead to bone loss and implant failure.

Compartment Syndromes of the Lower Leg

Compartment syndromes are disorders of the extremities in which increased tissue pressure compromises the circulation to the muscles and nerves within the space (see Chapter 15). These conditions are most common in the lower part of the leg, where four natural compartments exist (anterior, lateral, deep posterior, and superficial posterior). The anterior compartment is most commonly involved.

TREATMENT

Chronic cases usually subside with rest, but fasciotomy is occasionally performed to prevent recurrence. The acute form requires immediate surgical decompression. Without treatment, necrosis of muscle and nerve may occur and result in permanent weakness, contracture, and nerve dysfunction similar to Volkmann’s ischemic contracture in the upper extremity (see Chapter 2).

Injection and Aspiration Therapy

The ability of steroids to relieve pain and improve the function of inflamed joints, tendons, and bursae is unquestioned. And although a cellular inflammatory response is not always present in those disorders usually called “arthritis” and “tendinitis,” corticosteroid injections have been shown by randomized, controlled trials to provide excellent relief of pain in these conditions. The exact mechanism by which this is accomplished is unknown. It is theorized that these drugs reduce the local infiltration of those cells and compounds that mediate the inflammatory response. An increase in local blood flow and improvement in local tissue metabolism are other common explanations. A placebo effect is undoubtedly present in some cases. Systemic absorption is less after their use than it is with oral administration. However, some absorption does occur, and plasma cortisol levels can be suppressed for up to 1 week after injection. Markers of bone formation, such as osteocalcin, can also be depressed transiently but return to normal in 2 weeks after intraarticular use of a corticosteroid, while markers for bone resorption do not change, suggesting that there is no effect on bone resorption and only a temporary effect on bone formation.

The lidocaine and steroid may be injected separately but are usually mixed together. The use of a small amount of lidocaine alone for skin and soft tissue infiltration may be necessary in the apprehensive patient. If a joint with a thick capsule is to be entered, the capsule may also need to be infiltrated because passing a larger needle through the capsule may be uncomfortable for the patient. Do not use the steroid mixture to anesthetize the site; use only the anesthetic. Otherwise, atrophy may occur. The anesthetic is best injected with a 25-gauge needle (⅝-inch or 1 ½-inch). This needle size may also be used to inject the steroid–lidocaine mixture, especially if the injection is superficial. A 22-gauge, 1 ½-inch needle is sometimes necessary in deeper injections. A “giving” sensation usually occurs as the needle penetrates the tough, fibrous capsule, especially in the knee. The needle should not be advanced once the joint has been entered to avoid joint trauma. Aspirating the syringe while withdrawing the needle may prevent residual drops of the mixture from contaminating the skin and subcutaneous tissue.

The dose of cortisone is usually based on volume; 1 to 2 mL is used for larger joints and lesser amounts for smaller joints (Table 18-1). Tendons, except the quadriceps and elbow epicondyles, usually are not directly injected. Instead, it is usually a space (joint, tendon sheath or subacromial space) that is injected. There should be little resistance when injecting a space. If resistance occurs, the needle tip is probably incorrectly placed in some soft tissue, and its position should be changed. The volume of fluid injected depends on the size of the joint or soft tissue area.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree