Special Issues in Inflammatory Arthritis

Ian G. Kelly

I. G. Kelly: Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon, Glasgow Royal Infirmary, Glasgow, Scotland.

INTRODUCTION

The inflammatory conditions affecting the shoulder include rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and the seronegative spondyloarthropathies such as psoriatic arthritis, Reiter’s syndrome, and ankylosing spondylitis. Shoulder involvement in the seronegative spondyloarthropathies is uncommon, with the acromioclavicular joint being most commonly affected. This chapter will discuss the management of shoulder problems in the patient with RA. Emery et al.9 have presented an excellent account of shoulder problems encountered in patients with ankylosing spondylitis.

Rheumatoid arthritis is the most common inflammatory joint disease and is a prominent and often dominant part of rheumatoid disease, a systemic illness. The arthritis is polyarticular and can thus involve one or more parts of the complex of joints that comprise the shoulder.

PATHOLOGY AND DIAGNOSIS

Although the cause of rheumatoid disease remains unknown, the disease process involves a synovitis, a vasculitis, and secondary changes, such as anemia.

The initial changes are confined to the soft tissues, and it has been suggested that it is the synovial sheath of the intra-articular portion of the tendon of the long head of biceps that is first involved. It appears that the process commences with vascularization followed by hyperplasia of the synovium and the formation of pannus. Pannus is abnormal synovium that secretes hyaluronate, collagenase, proteolytic enzymes, and proteoglycan proteases, and thus contributes to joint destruction.

When the inflammatory process involves tendon sheaths, it is in a confined area and may infiltrate the tendon to a variable degree. The rotator cuff tendons do not have a synovial sheath, but the subacromial bursa is intimately connected to the superior surface of the supraspinatus tendon, which is always involved when there is a bursitis.

In addition to producing bony erosions, the rheumatoid process stimulates osteoclast activity through the secretion of prostaglandins and cytokines. This contributes to the osteopenia seen in these patients.

The wide variety of pathologic processes involved in rheumatoid disease are reflected in the diverse clinical presentations with different aspects dominating in different patients.

THE SHOULDER COMPLEX IN RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

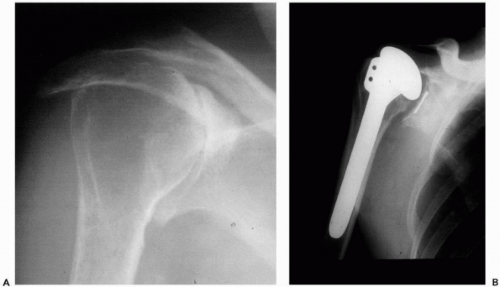

Involvement of the subacromial “joint” occurs in 10% to 15% of patients and is often seen in the absence of radiologic evidence of disease in other parts of the shoulder. In some patients, the bursa is very large (Fig. 24-1) and will contain multiple “melon seed” bodies, but in most it is not palpable. Because of the intimate relationship of the bursa to the rotator cuff, large bursae are usually associated with cuff deficiency or tears.

The acromioclavicular joint is said to be involved in up to 55% of symptomatic shoulders.10,39 Dijkstra et al.,8 in a

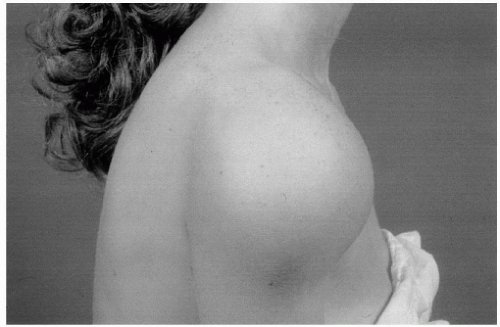

radiologic study, indicated that acromioclavicular (AC) joint involvement was independent of the extent of glenohumeral disease. Local tenderness is usually present, and, rarely, synovitis will be palpable, although this may be a herniation from the subacromial bursa. At the AC joint, there is a widening of the joint space with increasing severity of rheumatoid involvement (Fig. 24-2). However, it should be noted that typical degenerative changes with narrowing of the joint space can be seen, especially in patients who develop RA in later life.

radiologic study, indicated that acromioclavicular (AC) joint involvement was independent of the extent of glenohumeral disease. Local tenderness is usually present, and, rarely, synovitis will be palpable, although this may be a herniation from the subacromial bursa. At the AC joint, there is a widening of the joint space with increasing severity of rheumatoid involvement (Fig. 24-2). However, it should be noted that typical degenerative changes with narrowing of the joint space can be seen, especially in patients who develop RA in later life.

Figure 24-1 Very large subacromial bursa. It contained numerous “melon seed” bodies, and the rotator cuff was thinned with a number of small perforations. |

Figure 24-2 Larsen classification for the acromioclavicular joint.27 Note the widening of the joint space with increasing severity of disease. |

The glenohumeral joint is not involved clinically as often as the subacromial or acromioclavicular joints,21 but radiologic involvement is common. Ennevara10 found changes in 67.5% of his patients.

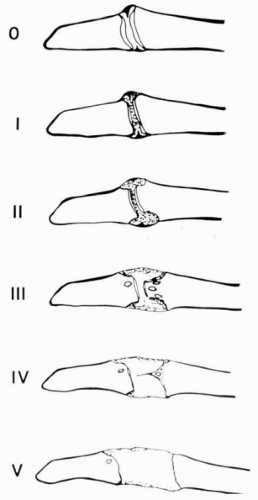

The most widely used grading system is that of Larsen et al.27 It has stages for both the acromioclavicular joint and the glenohumeral joint (Fig. 24-3). The system was not constructed as a clinical classification, although there is a tendency for the radiologic changes to pass through these stages as the severity increases. Lehtinen et al.28 demonstrated that the subacromial space decreases significantly between Larsen grades III and IV, indicating that substantial rotator cuff pathology had developed.

In a recent study, Olofsson et al.36 found shoulder involvement in 50% of 80 patients who had RA for a median period of 8 months; 30 patients had evidence of reduced shoulder function in at least one shoulder. Decreased function was associated with higher disease activity. Thus, the shoulder complex is not only frequently involved in RA but also involved from an early stage. However, not all affected shoulders progress.

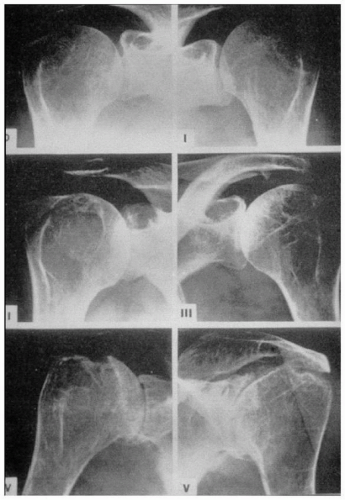

From a surgical point of view it is important to be able to identify the shoulder that will progress. Hirooka and colleagues18 contributed to our understanding of this when they reported five radiologic patterns of disease in the rheumatoid shoulder in a group of 83 patients (133 shoulders) followed for 5 to 23 years (mean 14 years) (Fig. 24-4). Significantly, the largest group was the nonprogressive type (74 shoulders), in which there was only osteopenia or minor erosions at 15 to 20 years. The

second type was “erosive” (22 shoulders), in which there were marginal erosions but the articular surface was well preserved until 10 years after the onset of the disease, after which joint destruction progressed slowly. The “collapse” pattern was the most commonly seen (34 shoulders), and these shoulders developed osteopenia rapidly with associated subchondral cysts. This progressed to collapse of the subchondral bone and advanced joint destruction after 5 to 10 years. The “arthrosis” group (12 shoulders) showed osteophytes and subchondral sclerosis with joint structure being well preserved for a long time. Finally, the mutilans group (14 shoulders) showed extensive and rapid bone resorption.

second type was “erosive” (22 shoulders), in which there were marginal erosions but the articular surface was well preserved until 10 years after the onset of the disease, after which joint destruction progressed slowly. The “collapse” pattern was the most commonly seen (34 shoulders), and these shoulders developed osteopenia rapidly with associated subchondral cysts. This progressed to collapse of the subchondral bone and advanced joint destruction after 5 to 10 years. The “arthrosis” group (12 shoulders) showed osteophytes and subchondral sclerosis with joint structure being well preserved for a long time. Finally, the mutilans group (14 shoulders) showed extensive and rapid bone resorption.

Figure 24-3 Standard reference films for the Larsen classification27 of the glenohumeral joint. |

Neer33 described four patterns of the rheumatoid shoulder. These were wet, dry, resorptive, and end stage. The terms were purely descriptive and not related to presentation. Hirooka et al.18 compared their patterns with those described by Neer and believed that there was some overlap of their patterns with his. My experience suggests that the patterns of Hirooka et al. match those of Neer very

closely with the “wet” corresponding to the “erosive,” the “resorptive” corresponding to the “collapsing,” and the “dry” corresponding to the “arthrotic.”

closely with the “wet” corresponding to the “erosive,” the “resorptive” corresponding to the “collapsing,” and the “dry” corresponding to the “arthrotic.”

Applying these terms to the preoperative radiographs of 104 shoulders undergoing arthroplasty, we found 30 “wet” shoulders, 10 “dry” shoulders, 56 “resorptive” shoulders, and 8 end-stage shoulders. The operative findings were correlated with the patterns. Of the 30 wet shoulders, 15 were found to have normal glenoid bone stock; they were the only shoulders in the group to have this. Further, 21 of the 30 wet shoulders had ruptured rotator cuffs, with the remainder all being described as “thin.” Four cuff tears were found in the 56 resorptive shoulders, 2 in the 10 dry shoulders, and 4 in the 8 end-stage shoulders. All of the shoulders in the resorptive group had thin rotator cuffs.

Our own study relates the soft tissue changes to the observed patterns, and, together with the data from Hirooka et al.,18 provides some indication of the likely rate and type of progression of glenohumeral disease in the rheumatoid shoulder. Thus, the wet shoulder is a shoulder “at risk” with a high incidence of cuff rupture, which often occurs before there is a significant amount of bony damage. Crossan and Vallance7 drew attention to this subgroup in their classification, emphasizing that cuff failure could occur acutely and before significant bony damage was evident. In contrast, the “dry” pattern appears to be protective. Although a consecutive group of 53 rheumatoid patients with shoulder pain contained 16 “dry” shoulders, the group of 104 shoulders undergoing shoulder arthroplasty contained only 10 with the “dry” pattern.

ASSESSMENT OF THE EXTENT OF SHOULDER DISEASE

The frequent radiographic appearance of superior subluxation of the humeral head (Fig. 24-5) resulted in the belief that rotator cuff rupture was common in RA. However, studies by Neer et al.,34 Cofield,6 Kelly et al.,23 Sledge et al.,45 Sneppen et al.,46 and Stewart and Kelly49 demonstrated that between 70% and 80% of these shoulders have intact rotator cuffs, although the majority will be abnormally thin. This thinning, together with the cephalic destruction of the glenoid, contributes to the radiographic superior subluxation. Ultrasound can be valuable for studying the state of the rotator cuff or for assessing the state and extent of the subacromial bursa.19 In advanced disease, the bony deformity and limitation of motion can make this technique difficult to use and interpret.

Computed tomography (CT) can be very useful in assessing the bone stock available for arthroplasty1,32 both in the humeral head and the glenoid. Plain radiographs are

usually sufficient to assess the humeral head, but if a cup arthroplasty is to be used, CT scanning will sometimes demonstrate the presence of large cysts within the head that cannot otherwise be seen. Glenoid erosion is usually central in RA, but significant glenoid bone loss in a cephalic direction is occasionally encountered. Again, plain radiographs usually suffice, but CT scanning should be performed if there is any doubt about bone stock.

usually sufficient to assess the humeral head, but if a cup arthroplasty is to be used, CT scanning will sometimes demonstrate the presence of large cysts within the head that cannot otherwise be seen. Glenoid erosion is usually central in RA, but significant glenoid bone loss in a cephalic direction is occasionally encountered. Again, plain radiographs usually suffice, but CT scanning should be performed if there is any doubt about bone stock.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the rheumatoid shoulder has been widely reported. Kieft et al.25 demonstrated the range of pathology in the glenohumeral joint but found that the acromioclavicular joint was difficult to image. They also commented that damage to the soft tissues was present even when radiographs showed normal results. I have not found MRI to be particularly useful in the surgical management of patients with rheumatoid shoulders.

THE PATIENT

Matsen et al.30 demonstrated that patients with RA presenting for shoulder arthroplasty had significantly more health impairment than patients with osteoarthritis presenting for the same procedure. In patients with RA, shoulder surgery should never be performed without considering the state of other joints and the overall health and function of the patient. If the shoulder problem is part of a generalized flare of the disease, assessment is difficult and may not be reliable. Appropriate medical measures should be instituted, and the patient should be reviewed at a later date. I prefer not to operate on patients who are having a flare of disease. Although some flares will settle after surgery, some will not, and this is likely to adversely affect their rehabilitation.

Cervical spine disease may be present in up to 80% of patients with RA with severe disease.20 This is usually at the atlanto-axial joint, but subaxial problems and vertical subluxation or cranial settling will also be seen. Because a high proportion of patients with significant subluxation will be asymptomatic, it is important to assess the cervical spine in all rheumatoid patients undergoing surgery to avoid problems during intubation or positioning. Flexion and extension lateral projections suffice in most patients, but if there is a suspicion of a myelopathy, MRI should be used.

There is little point in operating on the shoulder if problems with the ipsilateral elbow, wrist, and hand will not permit the limb to function. In such an instance, hand surgery should take precedence. Whether to operate on the elbow or shoulder first may be a difficult decision. If one is more painful than the other it would seem reasonable to deal with that joint first. However, a painful and unstable elbow can interfere with shoulder rehabilitation. Simultaneous ipsilateral shoulder and elbow arthroplasty has been reported26 with good results, matching those reported for separate surgery, and a recent long-term follow-up of a large series from the same unit has revealed durable results (Neumann, personal communication). In a study of 31 patients who had undergone ipsilateral shoulder and elbow arthroplasty at separate operations, Friedman and Ewald12 found that the results were as good as if either joint had been operated on alone. However, if the elbow was operated on first, there was a longer interval until the second operation, suggesting that this should be performed first. Gill et al.14 concluded that shoulder and elbow arthroplasty in RA were independent events and that the sequence and interval between them should be guided by clinical need alone.

The shoulder becomes a major load-bearing joint when the patient has to use walking aids, especially after lower limb surgery, which must be considered when planning the order of surgery in a polyarthritic patient.

The general functional status of the patient can be classified according to the American Rheumatology Association criteria reported by Steinbrocker et al.48

Grade I: Capable of all activities

Grade II: moderate restrictions—adequate for normal activities

Grade III: marked restrictions—self-care only

Grade IV: bed and/or chair—little or no self-care

Although this classification system gives a guide to the functional status of the entire patient, very few reports of shoulder surgery in the rheumatoid patient refer to it.13

WHERE IS THE PAIN FROM?

The location of the pain in the shoulder can provide a useful guide to the site of the pathology in some patients.24 However, the majority of rheumatoid patients present with pain felt over the point of the shoulder that radiates toward the area of the deltoid insertion and/or to the root of the neck.21 Local tenderness is a poor guide to the site of the problem, and radiographs and other imaging modalities correlate poorly with the clinical presentation.

In many patients, it is difficult to be certain of the site of the pain. In this situation, I use small injections of local anesthetic to locate the painful site(s).21 First, 1 mL of 1% lignocaine is injected into the joint most likely to be involved on the basis of clinical assessment. I then wait 2 to 3 minutes for the anesthetic to act before asking the patient to carry out previously painful movements. If the pain has been completely abolished, the test is complete. If the anesthetic has had no effect or has been only partially successful, I try another site, usually the acromioclavicular joint. The test is complete when total pain relief has been achieved or the glenohumeral joint has been injected. Failure to achieve relief from any of these sites should give cause to reconsider the source of the pain.

In our series of 75 shoulders assessed by using injection testing, the acromioclavicular joint was involved alone in

24, the subacromial joint was involved alone in 14, both joints were involved in combination in 21, and a glenohumeral joint injection was required in 16. Thus, despite 62 shoulders having Larsen III, IV, or V changes at the glenohumeral joint, 60% of this group experienced pain in a location other than the glenohumeral joint.

24, the subacromial joint was involved alone in 14, both joints were involved in combination in 21, and a glenohumeral joint injection was required in 16. Thus, despite 62 shoulders having Larsen III, IV, or V changes at the glenohumeral joint, 60% of this group experienced pain in a location other than the glenohumeral joint.

COORDINATING WITH THE RHEUMATOLOGIST

Patients with inflammatory joint disease typically run a variable course with intermittent flares of disease activity and polyarthritic involvement. Although there are still some centers where rheumatoid surgeons manage the patient’s entire case, the tendency, even in Europe, has been toward regional subspecialization among orthopaedic surgeons. Therefore, it is only the rheumatologist who sees the whole picture and is in the position to coordinate the medical and surgical treatment of these patients. However, this demands that the rheumatologist know the surgical procedures that are available and their indications. Close collaboration between surgeon and rheumatologist is essential.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree