| 8 | Special Arthrodeses for Infected Joints

|

These increasingly hectic times are characterized by demands for limitless mobility. To keep pace, technical progress has also been made in the surgical theater in clinics. Continually improved implants and constant changes in artificial joints make it difficult for doctors to obtain long-term experience with one certain procedure. One must not, however, forget that a surgeon’s or orthopedic surgeon’s individual learning curve means the patient’s suffering curve. Changing the implant used too often is counterproductive and increases the complication rate considerably.

Nonetheless, we surgeons nourish the patient’s belief that just about everything can be corrected. Every trauma and every degenerating process in the joints which has been going on for decades is expected to be rectified by the physician’s skill together with an optimal implant. Interestingly enough, both doctors and patients have contributed to the gradual development of this process in the clinical routine. For example, it is expected that a lower extremity which has suffered the severest traumatic injury can be salvaged and will even function after all reconstructive procedures have been applied. The surgeon is, of course, pleased and the patient happy when the leg need not be amputated. But, after getting used to the situation, instead of being satisfied both parties astoundingly became dissatisfied. Residual complaints are overrated, and new surgical procedures are considered. No one wants to remember the initial situation. This step, albeit well meant, often leads to complications. In individual cases the physician is well advised to say “no.” But this must be learned.

In this difficult situation, arthrodesis—stiffening of the joint—is considered a relic of the distant past. It is expected to destroy the patient’s mobility and create a permanent problem. If this procedure is recommended to a patient, the initial reaction is sudden doubt concerning the physician’s professional competence. “You can just as well amputate my leg right now,” is often the spontaneous reply. The patient has already suffered considerably. It is not taken into consideration that arthrodesis is often not the initial intervention, but is at the end of a long chain of operations and presents the possibility of painless or at least less painful use of the limb. If the individual case is critically analyzed from the physician’s point of view, this step should actually have been taken earlier in the chain of interventions. A correctly performed arthrodesis offers undeniable advantages for the patient:

• Full weight bearing on the extremity

• Little or no pain

• No further operations planned in the future

• In the long run, no need for ortheses or orthopedic shoes

This can, however, only be achieved if sufficient bone substance remains in the knee or ankle when the arthrodesis is performed.

It makes little functional sense for the patient if one extremity is much shorter due to bone defects because then he or she will permanently have to rely on walking aids. A difference in length of up to 3 cm can easily be compensated in or on a shoe. The patient can even walk short distances barefoot without uncertainty. Greater limb-length discrepancies limit mobility and quality of life and can even be dangerous, especially among the elderly.

Depending on the localization of the arthrodesis and the patient’s age and compliance, bone construction should be undertaken to equalize the difference in length. Whether bone grafting will be sufficient, callus distraction will be necessary, or an arthrodesis rod must be implanted (especially if there is a bone defect in the knee after numerous total knee replacements) to solve the problem, must be decided together with the patient and depends largely on the condition of the extremity. The goal must be to compensate the handicap of a stiff joint with optimal surrounding conditions.

An increasing number of total knee and ankle replacements are now being implanted worldwide. As the number of implants increases, so does the absolute number of complications. Under these circumstances, arthrodesis will revive. It offers patients the possibility to walk without pain in the majority of cases. If arthrodesis had been considered in the individual’s chain of treatment at a time when there was still enough bone substance, far better functional outcomes would be possible.

Under these considerations, arthrodesis could even be a primary option for young patients with completely destroyed knee or angle joints as a result of extreme traumas. Implanting an artificial joint, which is a justified therapeutic option for older individuals in such situations, should not be considered for young patients. They experience the severe resulting problems while they are still relatively young. Remember the inventor of the total hip replacement, Sir John Charnley (1911–1982), who wisely said, “The surgeon implants a disease with every total joint replacement.” This disadvantage does not exist with arthrodesis.

Knee Joint

Indications

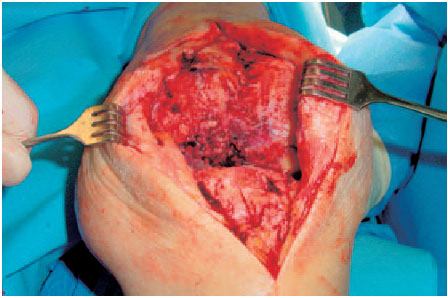

• Septic joint destruction (bone/ligament) (Fig. 8.1)

• Widespread osteomyelitis of the distal femur

• Widespread osteomyelitis of the proximal tibia

• Infected prosthesis

Fig. 8.1 Stage 4 infection of the knee joint with extensive destruction of the bone and complete loss of cartilage.

NOTE

A contraindication places the surgeon in a dilemma. One should always critically question the indication to amputate in such cases.

Older patients fare worse after an amputation than younger patients from a purely functional point of view. If the patient wishes to keep his/her leg in spite of considerable risk factors, there is no choice but to send the patient away or to comply with his/her (understandable) wish. In individual cases an arthrodesis rod which can bear weight early is a possible solution.

Providing information which cannot be misunderstood—for your own security—including all possible complications is an absolute necessity.

Contraindications

• Multimorbid patient

• Lack of compliance

• Life-threatening disease

• Severe arterial occlusive disease

NOTE

A false assessment of the patient’s compliance and especially of his/her subjective satisfaction after arthrodesis can cause the surgeon considerable problems afterwards. The patient often cannot imagine—despite sufficient verbal information—how life functions with a stiff knee. Medical guidance of the patient during the entire duration of treatment and thereafter is decisive. One possibility is to fit a brace for a few days preoperatively to give the patient an impression of what arthrodesis of the knee is like.

General Comments

The complex problems in destructive infectious joint disease of the knee are so multifaceted that different therapeutic options—arthrodesis versus total joint replacement—must always be discussed. The patient’s wishes have priority. Even if these wishes in some cases make no sense medically, the physician is bound to respect them.

The surgeon’s primary function is to offer advice; making demands or even applying pressure is simply not an option, regardless of contrary specialist opinion. The physician must never forget that any stiffening of the knee joint places considerable limitations on every patient. You can only try to convince the patient that a stiff knee joint is a safe option offering full weight bearing in the future, despite all functional restrictions.

If a patient is unsatisfied after successful arthrodesis, one should always consider whether the primary information and advice given to the patient was not sufficiently detailed.

ERRORS AND RISKS

Axial malalignment: It is difficult to judge the axial alignment intraoperatively with an image intensifier. Varus deformities often result.

Persisting infections: It can make sense to perform a two-stage arthrodesis, especially in osteomyelitis of the adjacent areas (femoral condyle/tibial head).

Insufficient resection—to avoid extreme shortening of the leg—increases the danger of reinfection. If the infection is confined to the joint, this danger does not exist.

Nonconsolidation of the bone.

Functionally unsatisfactory shortening of the leg: especially after repeated infections of total knee replacements and final removal of the prosthesis, a shortening of the leg by > 4 cm is usually the result. Depending on the age of the patient and his/her risk factors, lengthening the shortened leg in the arthrodesis cleft can avoid this functionally unsatisfactory situation. For injury to nerves and vessels, see below.

Surgical Concepts

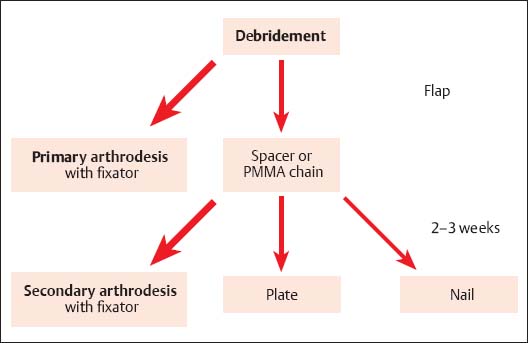

Eradication of the focus of infection and reconstruction by means of arthrodesis can be performed in either one-or two-stage procedures (Table 8.1). The decision is determined by the following situations:

• Extent of the infection

• Intensity of the infection

• Patient’s condition

• Soft-tissue defects

• Bone grafting

• Stabilizing procedures

“Infection and metal are poor partners.” This guiding principle, which is supported by every clinical routine when sepsis is involved, recommends a two-stage intervention for planned joint stabilization with an implant. After debridement (Fig. 8.2), a local antibiotic is inserted (spacer or polymethylmethacrylate [PMMA] chain). Immobilization is achieved with a cast or anterior clamps (fixator).

NOTE

Arthrodesis is indicated if there is manifest joint destruction. Antibiotics alone or even injections are not appropriate therapy in such cases.

Adjuvant antibiotic administration according to the results of bacteriologic testing is correct therapy.

Soft-tissue defects are closed with a gastrocnemius flap or free flap (very rarely) immediately after debridement. The most common soft-tissue defects are treated by shortening the leg alone.

Table 8.1 Criteria for deciding whether to perform a one- or two-stage procedure

One-stage procedure | Two-stage procedure | |

|---|---|---|

Extent of infection | Knee joint | Osteomyelitis |

Intensity of infection | Chronic | Acute, purulent |

Patient’s condition | Healthy | Sick |

Bone grafting | Not necessary | Necessary |

Stabilization | Fixator | Plate/nail |

Fig. 8.2 Therapeutic concept for destructive infection of the knee joint.

Principal Signs and Symptoms

• Classical parameters of inflammation

• Fever

• Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (leukocyte count is unspecific)

• C-reactive protein (CRP) is almost always elevated

• Pain on movement

• Fistulas may be present

Surgical Preparations

• Radiograph: Further imaging diagnostics are only required in exceptional situations.

• Smear: It is good policy to aspirate the joint before the operation so that adjuvant antibiotic therapy can be performed according to the most recent bacteriologic test results (e.g., methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, MRSA). In an acute emergency this may not be possible if it causes delay.

• Perform routine laboratory tests.

• Have four units of banked blood ready and available.

• Obtain informed consent from the patient, including:

– General risks

– The entire spectrum of problems, like “stiff knee”

– Possible necessity of a blood transfusion

– Axial malalignment

– Rotational error

– Shortened leg

– Nerve damage, for example, peroneus, sciatic nerves

– Vascular damage, for example, popliteal vessels

– Failure of bone consolidation

– Recurring infection

Special Instruments and Materials

• Oscillating saw

• Water-cooled round burr

• Broad chisel

• Jet lavage

• PMMA chains, Refobacin Bone Cement R, gentamicin sponge

NOTE

Possible complications must be written down. General comments like “damage to nerves or vessels” are not sufficient. It is important to be precise, for example “damage to the peroneal nerve.”

Therapeutic Concept: Eradication of the Infection by Means of Primary Arthrodesis with an External Fixator

Soft Tissues

• Begin intravenous antibiotic administration approximately 30 minutes before the operation. Interrupt the blood supply. Inflate the tourniquet.

• Perform a central vertical incision to open the knee joint on the medial parapatellar side (Fig. 8.1).

• Take biopsies for bacteriologic and pathologic examination. Smears should no longer be taken without biopsies because the two together considerably increase identification of pathogens.

• Radically debride all infected soft tissues.

• Perform initial jet lavage (to reduce the number of pathogens).

• Eliminate existing or beginning soft-tissue defects with flaps (gastrocnemius or free flap).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree