CHAPTER 4 Spacer Devices—Old and New

Bone and joint preservation are the main goals of treatment of unicompartmental osteoarthritis, especially in younger patients.

Bone and joint preservation are the main goals of treatment of unicompartmental osteoarthritis, especially in younger patients. Knee osteotomies provide the adjustment of leg axis malalignment, but do not address rebuilding the worn cartilage surface of the compartment.

Knee osteotomies provide the adjustment of leg axis malalignment, but do not address rebuilding the worn cartilage surface of the compartment. Unilateral knee arthroplasty calls for bone resection and has shown shorter durability than total knee arthroplasty.

Unilateral knee arthroplasty calls for bone resection and has shown shorter durability than total knee arthroplasty. Early unilateral implants such as the McKeever tibial hemiarthroplasty have addressed this problem without bone resection, with single-surface tibial resurfacing, and with reasonable long-term results. Later the UniSpacer, a self-centering mobile unilateral interpositional metal implant, was introduced, but failed because of inadequate alignment and its tendency for dislocation.

Early unilateral implants such as the McKeever tibial hemiarthroplasty have addressed this problem without bone resection, with single-surface tibial resurfacing, and with reasonable long-term results. Later the UniSpacer, a self-centering mobile unilateral interpositional metal implant, was introduced, but failed because of inadequate alignment and its tendency for dislocation. Recently, based on the principles of the nonfixed implants, the iForma, an individual metal interpositional device, was developed using patients’ individual magnetic resonance imaging data, mimicking the shape of the affected joint compartment. The iForma device can provide improvement in knee function and reduction in pain within a narrow indication of patients with unicompartmental knee arthritis, but with a significantly higher risk of early revision compared to traditional unicompartmental arthroplasty.

Recently, based on the principles of the nonfixed implants, the iForma, an individual metal interpositional device, was developed using patients’ individual magnetic resonance imaging data, mimicking the shape of the affected joint compartment. The iForma device can provide improvement in knee function and reduction in pain within a narrow indication of patients with unicompartmental knee arthritis, but with a significantly higher risk of early revision compared to traditional unicompartmental arthroplasty.Early Development of Hemiarthroplasty

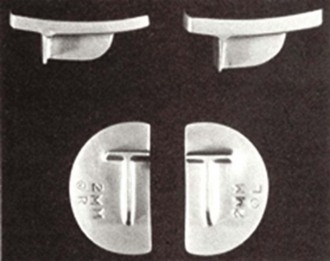

For patients with osteoarthritis limited to a single femoral-tibial compartment, the concept of a metallic hemiarthroplasty has a long history. The genesis of the concept of using an iPD, in which a material is placed between the condyles within the joint to reduce wear or prevent adhesion, goes back almost 150 years, when it was first suggested by Verneuil.1 Over the ensuing years, a wide variety of materials were tried, ranging from chromicized pig bladder in 1918 to vitallium in 1940. In 1960, McKeever2 described a metallic prosthesis that was designed to be placed in the femorotibial compartment and fixed to the tibial condyle (Howmedica, Rutherford, NJ) (Fig. 4–1). This design was subsequently modified by MacIntosh. Metallic hemiarthroplasty was introduced into orthopaedic practice in the 1950s and 1960s by McKeever2 and MacIntosh.3 MacIntosh and Hunter described the hemiarthroplasty approach as follows: “The aims of hemiarthroplasty are to correct the varus or valgus deformity by inserting a tibial plateau prosthesis of appropriate diameter and thickness to build up the worn side of the joint and thus to restore normal stability of the knee, to relieve pain and to improve function and gait. The collateral ligaments usually maintain their own length in spite of long-standing varus and valgus deformity, and stability is maintained by a prosthesis that is thick enough to correct the deformity and to take up the slack of the collateral ligaments.”4

Reports of early experience with both of these devices were generally encouraging. The two approaches differed primarily in the method of fixation. The McKeever implant had a keel that was inserted into the tibial condyle to provide mechanical fixation. In contrast, the MacIntosh implant was “held in position by the anatomy of the knee joint, and stability depends upon the taut collateral ligaments. No additional fixation is necessary. The top of the prosthesis has a contoured surface with rounded edges to provide the condyle with a permanent low-friction area. The undersurface is flat with multiple serrations to ensure a snug fit and stability.”4 In a series reporting 10-year follow-up for 75 MacIntosh implants, Wordsworth et al. found that 11 (14.7%) had been revised to arthroplasty and concluded that, although “greater angular deformities pre-operatively reduced the chance of success in the medium term, late failure of the arthroplasty after five years was very rare.”5 In a more recent clinical report on 44 McKeever implants followed for an average of 8 years, Scott et al. noted that, at final follow-up, 70% of the knees were rated as good or excellent.6 Similarly, Emerson and Potter also reported good results in 61 McKeever implants followed for up to 13 years (average, 5 years), in which 72% were rated as having good to excellent results.7 The most recent report of long-term results, published by Springer et al. in 2006, continued to show excellent long-term results with tibial hemiarthroplasty using the McKeever device.8 In spite of reports of early experience with these prostheses that were generally encouraging, the approach gained only limited use within the orthopaedic community due to its invasive nature and the subsequent development of total knee arthroplasty.