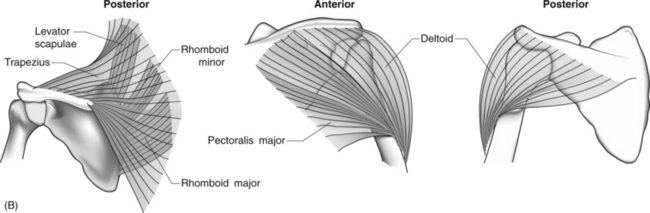

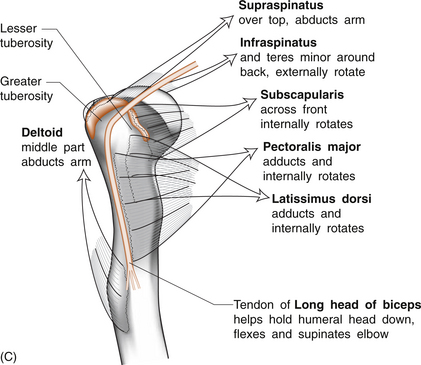

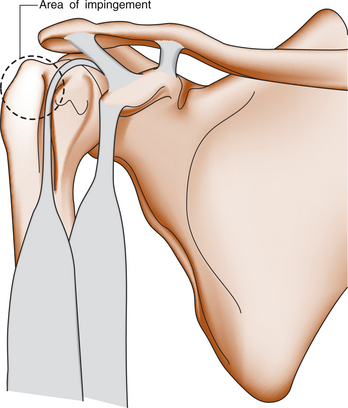

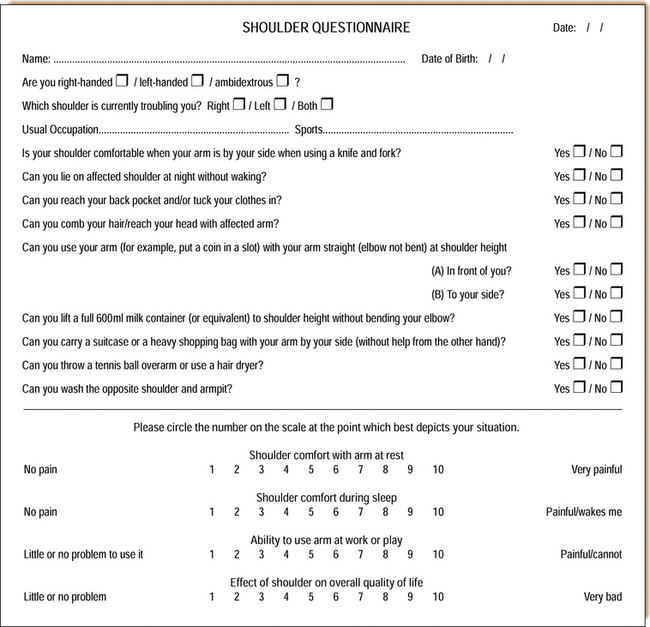

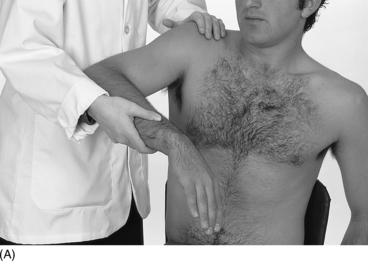

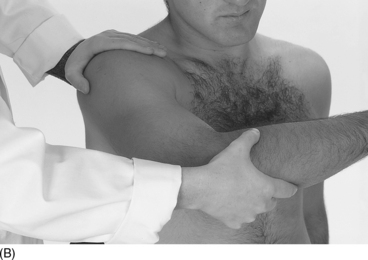

2 David H. Sonnabend In the musculoskeletal system, disorders of the soft tissues (muscles, tendons, ligaments, fascia, capsules, etc.) are often considered separately from those of the hard tissues (bone and cartilage). Indeed ‘soft tissue rheumatism’ is a term frequently applied to miscellaneous disorders causing musculoskeletal pain arising from structures outside the joint, such as bursae, tendons, ligaments and muscles. ‘Fibromyalgia’ is also sometimes included under this heading, but will be considered separately in Chapter 8. Upper limb pain in general, and shoulder pain in particular, is commonly due to disease of these soft tissues. Careful history-taking often provides a provisional diagnosis. Different age groups suffer different pathologies. Physical examination should be both general and directed towards the most likely diagnoses. Specific investigations, some of them expensive, should be used thoughtfully, and not in a shotgun fashion. Multiple modalities of treatment should be considered and may be employed simultaneously. These include rest, physical modalities, such as ice and heat, physiotherapy, specific exercise programmes (including stretching and strengthening), and both non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication and corticosteroids by injection. Surgery is sometimes the definitive treatment, and in appropriate cases should not be delayed unduly. The scapula is held on and moves on the chest wall. This connection is called the ‘scapulothoracic articulation’. The humerus is, in turn, attached to the scapula by the glenohumeral joint, where the head of the humerus sits on the glenoid surface of the scapula (Fig. 2.1A). While this may be seen as a ‘ball and socket’ joint, the socket is very shallow, almost a plate. Shoulder movement occurs simultaneously at both the glenohumeral and the scapulothoracic joints, in a ratio of approximately two to one. The scapular motors are large muscles which stabilize and move the scapula on the chest wall. They includethe serratus anterior, which protracts the scapula, and the trapezius, levator scapulae and rhomboids which elevate and rotate it (Fig. 2.1B). Paralysis of the serratus produces ‘winging’ of the scapula. Paralysis of the trapezius allows the shoulder to ‘drop’, and this may stretch the brachial plexus. A number of other muscles connect the humerus to the scapula and provide fine control. The largest of these are deltoid and subscapularis. The deltoid can be regarded in three parts: anterior, middle and posterior. Anterior deltoid (between clavicle and acromion superiorly and humerus inferiorly), can forward-flex the humerus. The lateral deltoid (arising from the side of the acromion), helps abduct the arm. The posterior deltoid extends the arm. All three parts acting together pull the arm up and abduct it. The subscapularis, arising on the deep surface of the scapula, runs across the front of the glenohumeral joint to attach to the (lesser tuberosity of the) humeral head. The supraspinatus muscle comes from the dorsal (superficial) surface of the scapula above its spine (hence supraspinatus). Its tendon passes over the top of the glenohumeral joint to the front of the greater tuberosity of the humeral head (Fig. 2.1C). Infraspinatus and teres minor arise from the dorsal surface of the scapula below its spine, and cross over the back of the glenohumeral joint to the back of the (greater tuberosity of the) humeral head. The supraspinatus helps with forward flexion and abduction, subscapularis with internal rotation, and infraspinatus and teres minor with external rotation. Although supra- and infraspinatus and teres minor are separate muscles, their flat sheet-like tendons of insertion blend with each other as they approach the humeral head to form a cuff that holds the humeral head in place and assists with active elevation and rotation of the shoulder. This blended combined tendon is referred to as the rotator cuff. The commonest site of pathology is in the supraspinatus tendon. The supraspinatus runs under an arch formed by the coracoid, the coracoacromial ligament and the anterior acromion (Fig. 2.2). Rubbing of the tendon on the undersurface of this arch produces the ‘subacromial impingement syndrome’, which is common in patients over the age of 40. Typically, impingement is related to repetitive overhead activity causing repeated pinching of the cuff beneath the arch. This may be exacerbated by an associated bone spur on the undersurface of the anterior acromion. The repetitive activity may be sports-related (golf swing, tennis serve or throwing) or work-related, but many impingement cases appear entirely idiopathic. It is not clear whether acromial spurs are the primary cause of impingement or whether they form in response to impingement. The site of pain is important. Subacromial pain is usually felt at the front of the shoulder. Radiation of pain to the deltoid insertion is common but non-specific, as it also occurs with glenohumeral pathology and cervical pathology, especially a C5 radiculopathy (nerve root lesion). Involvement of the trapezius, the parascapular muscles and the side of the neck are also common but relatively non-specific. Pain over the posterior joint line is frequently glenohumeral in origin. Involvement of the hand may suggest neurological or neurovascular pathology, including neck pathology, thoracic outlet syndrome or even carpal tunnel syndrome (see Ch. 3). Regional pain syndromes may also involve both shoulder and hand. It is important to assess the patient’s degree of disability. An inability to attend to activities of daily living, and particularly an inability to sleep at night, warrants serious attention, as does any condition which affects the patient’s occupation. For a keen sportsperson, an inability to throw or to serve at tennis may be equally distressing. The use of patient questionnaires and visual analogue scales aids assessment. A typical patient-questionnaire directed at the assessment of shoulder pain is shown below (Fig. 2.3). Questionnaires do not replace history taking. They can be repeated at later dates to help assess progress. Inspection and palpation are best carried out with the examiner standing behind the seated patient. When present, significant wasting of the spinati muscles will be obvious in all but the most obese patients. The best-known tests for subacromial impingement are the Neer and Hawkins tests (Fig. 2.4). In both, the greater tuberosity, the attached supraspinatus tendon, the overlying bursa and the adjacent biceps tendon are compressed beneath the coracoacromial arch. If either manoeuvre recreates typical symptoms, this suggests cuff impingement, but may also reflect biceps pathology. Yergason’s test for biceps tendinitis is less sensitive but moderately specific (Fig. 2.5).

SOFT TISSUE RHEUMATIC DISEASE INVOLVING THE SHOULDER AND ELBOW

Introduction

Anatomy of the shoulder

Muscles

The rotator cuff

Pathophysiology of rotator cuff disease

Clinical aspects of shoulder pain

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree