Soft Tissue Knee Injuries (Tendon and Bursae)

Bryan J. Whitfield

John J. Klimkiewicz

BIOMECHANICS OF TENDON RUPTURES

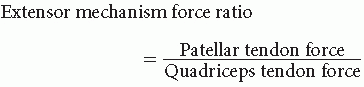

Position of knee flexion directly affects this ratio. At knee flexion angles < 45 degrees, this ratio is > 1, whereas at knee flexion angles > 45 degrees, this ratio is < 1 (16).

At > 45 degrees, the patellar tendon has a mechanical advantage and is less susceptible to injury through tensile failure, whereas at positions < 45 degrees, the quadriceps tendon has a mechanical advantage and is less vulnerable to injury.

Tendon strain in response to tensile load is up to three times greater at the insertion sites than at the tendon midsubstance. Additionally, collagen fiber stiffness is less at the insertion sites. These biomechanical properties contribute to tendon rupture commonly occurring at their insertion sites rather than at their midsubstance (50,51).

Failure usually occurs during rapid eccentric muscular contraction when markedly higher forces can be generated as compared to concentric muscular contraction (12).

This most often occurs with trauma causing forced extension of a flexed joint.

Several metabolic diseases or direct steroid injection can predispose to tendon rupture. These conditions include hyperparathyroidism, calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease (CPPD), diabetes mellitus, chronic renal disease, gout, systemic lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis (11,50).

PATELLAR TENDON RUPTURES

The patellar tendon receives its blood supply from the vessels within the infrapatellar fat pad and retinacular structures (2,45).

The origin and insertion of the patellar tendon are relatively avascular.

Ruptures of the patella tendon most typically occur in patients less than 40 years of age and are frequently associated with sporting activities including football, basketball, and soccer (33).

Ruptures are most common through the tendon-bone junction at the distal pole of the patella.

Histologic examination of rupture tendon often demonstrates an area of degeneration thought to predispose these patients to injury.

Clinical Presentation

At time of injury, a pop is often heard with an acute onset of pain and swelling. Patient is usually unable to actively extend knee or maintain it in an extended position against gravity. Chronic cases present with an extensor lag (33).

A palpable defect is commonly present just below the distal pole of the patella.

Concomitant ACL injuries are not uncommon and should be clinically ruled out.

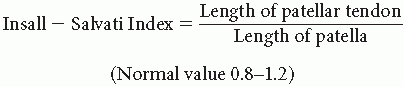

Plain radiographs often demonstrate a patella alta in comparison to the opposite knee using the Insall-Salvati Index (> 1.2)(1).

An osseous fragment is present at times at the distal pole of the patella when an avulsion is part of the injury.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful in cases where partial injury is suspected.

Treatment

Partial tendon injuries can be treated conservatively by cylinder cast or brace with the leg placed in full extension for 4-6 weeks followed by progressive range of motion and strengthening.

Complete ruptures should be directly repaired on an acute basis through transosseous drill holes through the patella. Once secured, the knee should have at least 90 degrees of flexion to avoid overconstraint. Primary repairs are often augmented with wire, mersilene tape, suture, or autologous hamstring tendon or iliotibial band (27).

Chronic ruptures can involve proximal patellar migration and can often require quadriceps mobilization or V-Y advancement in order to restore patellar height.

Semitendinosus/gracilis augmentation is recommended in the chronic scenario. Achilles tendon or patellar tendon allograft has often been found useful to replace/reinforce the reconstruction in chronic situations (17).

Complications

After surgery, complications include knee stiffness and weakness. Rerupture is rare. Restoration of normal patellofemoral tracking and height at the time of surgery is essential to achieve optimal results. Residual weakness of extensor mechanism is more common in delayed repairs.

QUADRICEPS TENDON RUPTURES

The quadriceps tendon is a coalescence of tendinous portions of the rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, and vastus medialis muscles.

The quadriceps tendon receives its vascular supply from an anastomotic network including the lateral circumflex femoral artery, descending geniculate artery, and medial/lateral geniculate arteries (40).

There is an avascular region of the deep part of the quadriceps tendon measuring 1.5 × 3.0 cm.

Ruptures of the quadriceps tendon most typically occur in patients over 40 years of age and are three times more frequent than patella tendon ruptures. Unilateral injuries are up to 20 times more frequent than bilateral injury (18).

The site of rupture usually occurs through a degenerative area within the tendon and seldom occurs in younger individuals. Systemic disease can lead to tendon degeneration and predispose to infrequent bilateral tendon ruptures (29).

Clinical Presentation

Pain is often present before rupture. At time of injury, a pop is often heard with an acute onset of pain and swelling.

In cases of partial injury or complete injuries that do not extend to include the retinacular tissue, the patient may be able to extend and resist gravity with an associated extensor lag, but in complete injuries, this is not possible.

A palpable defect at the site of rupture is usually felt just superior to the proximal pole of the patella.

Plain radiographs often demonstrate patellar baja, an avulsion of the superior pole of the patella, spurring of the superior patellar region, or calcification within the quadriceps tendon. Insall-Salvati Index is less than 0.8 (1).

MRI is a useful adjunct study because it can demonstrate partial ruptures or preexisting disease within the quadriceps tendon.

Treatment

Partial tears are often responsive to conservative treatment when the patient presents primarily with pain and has little loss of strength, retaining the ability to actively extend the knee against gravity.

Conservative treatment consists of a long leg cylinder cast in full extension for 4-6 weeks, with progressive range of motion and strengthening thereafter for partial injuries.

Complete ruptures respond best to immediate surgical repair in a direct end-to-end fashion after tendon debridement of necrotic tissue or with transosseous tunnels through the patella (42).

Chronic rupture involving more significant tendon retraction often require quadriceps tendon advancement through a tendon Z-plasty or V-Y tendon lengthening and advancement technique. Interpositional autograft/allograft tendon has been used with success in this scenario (46).

Success of repair is directly related to the length of time between injury and the time of surgery, with more chronic repairs producing less favorable outcomes. Age is also a factor, with better results in younger patients (26).

The most common complications after surgery or conservative treatment include decreased quadriceps strength/function with an associated extensor lag and lack of knee flexion.

GASTROCNEMIUS RUPTURE

Often referred to as tennis leg.

Traumatic injury to middle-aged athlete presenting as sudden pain in posterior proximal calf region. Significant pain, swelling, and ecchymosis usually occur with 24 hours.

Involves tearing of the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle typically at its musculotendinous junction (35).

Mechanism of injury combines ankle dorsiflexion in combination with knee hyperextension.

Differential Diagnoses

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree