Soft Tissue Injuries of the Leg, Ankle, and Foot

Keith Lynn Jackson II

Brian E. Abell

As the number of participants in both recreational and competitive activities increases, soft tissue injuries to the lower extremity are encountered more frequently by the primary care provider. If left untreated, these injuries could jeopardize participation and quality of life for those affected. The purpose of this chapter is to outline the characteristics and treatment of the more frequently encountered soft tissue pathologies by region.

SOFT TISSUE INJURIES OF THE LEG

The leg extends from the knee to the ankle. Some of the soft tissue injuries affecting this portion of the extremity include exertional compartment syndrome, posterior tibial tendon injury, and peroneal tendon injury.

Exertional Compartment Syndrome

Exertional compartment syndrome is activity-related pain caused by an increased intermuscular pressure within an anatomic compartment. In the leg, there are four compartments that contain muscle, blood vessels, and nerves. The compartments are enclosed by fascia, which limit muscular expansion during activity and can cause compression of the contents of the compartment. As pressure within the compartment approaches the mean arterial pressure, the blood flow through the microvasculature is diminished and ischemia ensues.

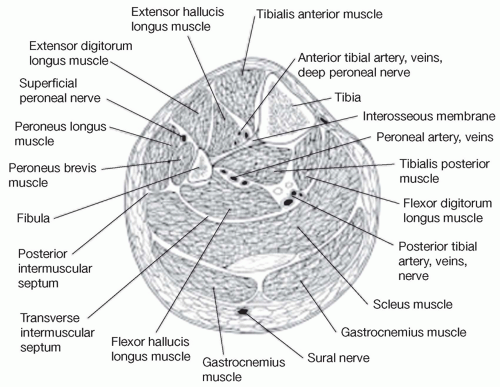

Knowledge of the anatomy of the lower leg is vital to the diagnosis of exertional compartment syndrome (Fig. 65.1). The anterior compartment contains the extensor hallucis longus, extensor digitorum longus, peroneus tertius, and tibialis anterior as well as the deep peroneal nerve. The lateral compartment contains the peroneus longus and brevis as well as the superficial peroneal nerve. The superficial posterior compartment contains the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles and the sural nerve. The deep posterior compartment contains the flexor hallucis longus, flexor digitorum longus, and posterior tibialis muscle as well as the posterior tibial nerve.

The patient is usually asymptomatic upon initiating exercise. The pain will begin at a predictable time during the workout. The pain is described as aching or cramping associated with feelings of swelling, fullness, or tightness. Dysesthesias often accompany the pain along the nerve within the affected compartment. Patients may also complain of altered running style. For example, a runner may state that the foot seems to be slapping the ground when the pain comes on.

Physical Examination

The physical examination at rest is often normal. In advanced cases, there may be tenderness to deep palpation along the affected compartment or a palpable fascial defect with hernia within the affected compartment.

Examination immediately after exercise reveals a firm, tender compartment with increased pain on passive stretch of the muscles within the compartment. Fascial defects with resultant herniations are more identifiable at this time.

Several techniques have been described for measuring compartment pressures: These include needle manometry, wick catheter, and slit catheter. Our preferred method of measuring compartment pressure is with a battery-operated, hand-held, digital, fluid pressure monitor. The Stryker Intracompartmental Pressure Monitor (Stryker Corporation, Kalamazoo, MI) is a convenient and easy-to-use measuring device.

Compartment pressures should be taken before exercise, 1 minute after exercise, and if necessary, 5 minutes after exercise. One or more of the following pressure criteria must be met in addition to a history and physical that is consistent with the diagnosis of exertional compartment syndrome. Preexercise pressure > 15 mm Hg, 1-minute postexercise pressure > 30 mm Hg, or 5-minute postexercise pressure > 20mm Hg (16).

Treatment

Nonoperative care generally consists of activity modification to levels below symptomatic threshold, ice, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and massage. The patient should be counseled that return to previous level of activity is likely to cause recurrence of symptoms.

A fasciotomy is the surgical treatment of an exertional compartment syndrome. In this procedure, the fascia is divided longitudinally over the entire length of the involved compartment. Indications for this procedure include an appropriate history for chronic exertional compartment syndrome,

a 1-minute postexercise compartment pressure greater than 30 mm Hg, or the presence of a fascial defect.

Figure 65.1: Cross-sectional anatomy of the compartments of the leg. © 2003 American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Reprinted from the Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, Volume 11(4), p. 268-276, with permission.

Posterior Tibial Tendon Injury

Injury to the posterior tibial tendon may occur acutely or as a component of chronic overuse syndrome. The posterior tibial tendon helps invert and plantarflex the foot and has an important role in maintaining the longitudinal arch.

Patients with posterior tibial tendon injury often report pain along the medial aspect of the leg posterior to the medial malleolus. The onset of symptoms is usually gradual with increases in such activities as walking, running, or jumping.

Physical Examination

There may be loss of the longitudinal arch and a clinical planovalgus deformity. When observing the patient from behind, the affected side will reveal more toes lateral to the heel than the unaffected side.

With an attempted single leg heel raise, there is loss of foot supination and heel inversion. In the later stages of posterior tibial dysfunction, patients cannot perform a single leg heel rise. In earlier stages of dysfunction, patients will perform the single leg heel rise in a slow deliberated fashion with associated pain.

There is tenderness and fullness along the course of the tendon.

Pain and weakness are present with resisted inversion.

Radiographic Examination

The x-ray evaluation should include standing anteroposterior and lateral views. The anteroposterior (AP) x-ray may show medial talar displacement in relation to the navicular. This is best seen with uncovering of the talar head. The lateral x-ray may reveal decreased height of the longitudinal arch and increased overlap of the metatarsals (20).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the test of choice to evaluate the posterior tibial tendon (20). Significant findings on MRI include heterogenous signal along the course of the tendon and possible increase in size.

Treatment

The initial treatment for posterior tibial tendon deficiency is generally nonoperative and begins with a period of immobilization with the use of a short leg walking boot or short leg walking cast. Once immobilization is complete, an orthotic should be used to support the arch and relieve stress on the tendon by posting the heel in a neutral position.

Corticosteroid injections are not recommended because of the risk of tendon rupture.

Surgery should be considered in those who do not respond to nonoperative management after 3-6 months, patients with loss of the arch, or patients with midfoot arthritis (13). Surgical options include synovectomy/debridement, flexor digitorum longus transfer, or calcaneal osteotomy.

Peroneal Tendon Injury

Peroneal tendon pathology is a commonly missed source of chronic lateral-sided ankle pain. The spectrum of peroneal tendon injury includes tenosynovitis, tendon tear, and peroneal tendon instability.

The peroneus longus originates from the proximal aspect of the lateral fibula. Its tendinous portion runs posterior to the lateral malleolus before inserting primarily onto the plantar proximal surface of the first metatarsal. Its function is primarily eversion and plantarflexion of the foot. The peroneus brevis originates from the lateral fibula. Its tendinous portion courses anterior and medial to the peroneus longus tendon at the level of the ankle and inserts onto the base of the fifth metatarsal. Its primary function is to evert the foot.

The patient will often complain of lateral ankle pain that localizes posterior to the lateral malleolus. The patient may also relay a history of pain, “popping,” and transient swelling in this area usually after an inversion injury.

Physical Examination

Pain and swelling over the course of the tendons posterior to the lateral malleolus will be present on examination. The patient may also report pain with resisted eversion of the ankle, passive inversion of the ankle, or resisted plantarflexion of the first metatarsal. In cases of peroneal instability, tendon subluxation or dislocation may be elicited with resisted eversion and dorsiflexion of the ankle.

Radiographic Examination

Standard radiographic review should include weight-bearing AP, mortise, and lateral x-rays.

Ultrasonography may show areas of heterogeneity within the tendons as well as subluxation.

Treatment

The initial treatment of peroneal tendon tenosynovitis begins with rest, ice, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications. An ankle brace or lateral heel wedge may also help alleviate symptoms. For more severe cases of tenosynovitis, the patient may be placed in a short leg cast or walking boot for a period of 2-4 weeks. In cases of peroneal tendon instability, nonoperative treatment is associated with a high rate of failure.

Corticosteroid injections are not recommended because of the risk of tendon rupture.

Operative intervention is indicated if symptoms persist after a trial on nonoperative care. Surgical treatment includes exploration, synovectomy, primary tendon repair, tenodesis, or retinacular repair.

SOFT TISSUE INJURIES OF THE HINDFOOT AND MIDFOOT

The hindfoot consists of the talus and calcaneus and their articulations, whereas the midfoot consists of the navicular, cuboid, and three cuneiform bones and their related articulations. Foot function hinges on the stability provided by the osseous anatomy and overlying soft tissue structures. Some of the more frequently encountered soft tissue pathologies affecting this region include os trigonum, jogger’s foot, tarsal tunnel syndrome, plantar heel pain, and posterior heel pain.

Painful Os Trigonum

The os trigonum is an ossicle present in 7%-11% of the population as a continuation of the posterior talar process. Painful os trigonum syndrome is one cause of posteromedial ankle pain. This syndrome is most prevalent in athletes who perform frequent or forced plantarflexion. The condition may be misdiagnosed as other conditions such as Achilles tendonitis (14).

Presentation is commonly with pain in the posterior medial ankle that may be worsened with plantarflexion activities (en pointe position in ballet).

Physical Examination

On examination, there may be tenderness to palpation over the os or the posteromedial ankle. Passive dorsiflexion/plantarflexion of the great toe may also illicit pain due to the close anatomic relationship of the flexor hallucis longus tendon and the trigonal process.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree