Soft Tissue Disorders About the Hip

Jeffrey A. Geller

Hip pain is a common complaint among patients seeking orthopedic attention and may range from simple ailments to more complex problems leading to extensive surgical reconstructions. Degenerative processes of the hip have been discussed in other sections of this text. This chapter will focus on the soft tissue structures about the hip that lead to pain, though several of these pathologies may occur in concert with more degenerative processes. In general, most soft tissue disorders around the hip are self-limiting and may be treated with nonoperative means. Other problems may lead to significant dysfunction necessitating operative intervention to help restore physical function. The aim of this chapter is to discuss the range of pathology that can affect the soft tissue structures about the hip.

Anatomy

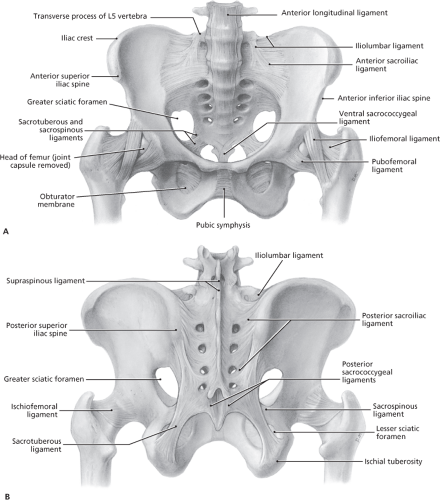

Specific knowledge of the soft tissue anatomy around the hip and pelvic region is integral to understanding soft tissue disorders of the hip. Skeletally, the hip is a ball and socket joint with several different muscle groups and ligamentous structures which provide support for normal function and excursion of the joint. Each is a complex grouping of muscles that interact to help propel the lower extremity forward in the gait cycle, or help the body rise from a seated position, including flexion, extension, rotation, and coronal movement. Though any of the muscle compartments about the hip are prone to soft tissue ailments, the lateral muscle complex including the hip abductor musculature and iliotibial band are the most commonly affected. This muscle group provides both abduction of the lower extremity, as well as balanced support of the pelvis, thus stabilizing the upper body against sway away from the midline (Fig. 43.1).

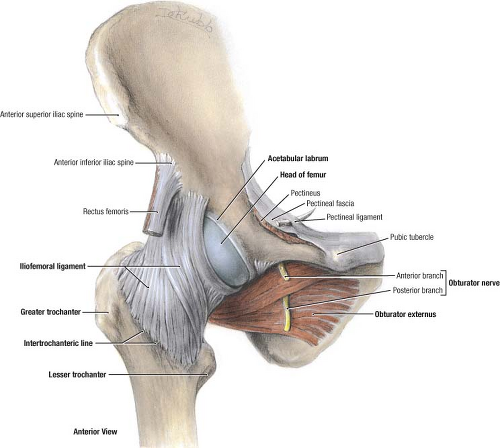

The anterior muscle group includes the superficial layer of muscles, specifically the sartorius and tensor fascia lata, and the deeper group consisting of the rectus femoris and the anterior border of the gluteus medius/minimus complex. There is also the distal extent of the iliopsoas muscle–tendon unit. The neurologic and vascular structures passing through this region consist of the femoral triangle structures, specifically the femoral nerve, artery, and vein. Similarly, the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve passes through the medial aspect of the tensor fascia lata, and is prone to compression as it penetrates the fascial plane (Fig. 43.2).

The medial group of muscles consists of the adductors. There are no significant soft tissue conditions commonly described in this section of the hip. Posteriorly, there is gluteus maximus superficially, with the short external rotators deeper. The main neurovascular conduit through this area is the sciatic nerve and the spectrum of structures passing through the piriformis fossa. Though structures may theoretically be at risk as they pass from the inner aspect of the pelvis, through the fossa, to the outer aspect, most structures are fairly mobile and pathologic conditions such as compression or occlusion do not seem to occur at such proximal points (Fig. 43.3).

The lateral muscle complex includes the muscular portion of the tensor fascia superficially, and the gluteus medius/minimus complex deep. Malfunction of this compartment has a profound effect on the function of the hip joint as it most directly affects the lever arm through the joint thus affecting the joint reaction forces (Fig. 43.4A).

It is important to have a thorough understanding of the bony anatomy of the lateral aspect of the hip as this helps with diagnosis of soft tissue conditions in this area including muscular and bony pathology (Fig. 43.4B). The lateral aspect of the greater trochanter consists of four different bony facets, the anterior, lateral, posterior, and superior facets. The gluteus minimus tendon inserts primarily onto the anterior facet, whereas the broader, larger gluteus medius muscle inserts primarily onto the lateral facet and the superior facet, with minor attachments to the posterior facet. There are bursae between both the gluteus medius and minimus and their respective bony facets overlying the greater trochanter (1,2).

Pathology

Pathologic conditions may be divided into intra-articular conditions and extra-articular conditions. Intra-articular conditions may include degenerative joint diseases, such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, or any of the conditions that lead

to arthritic states due to cartilage degradation. Other intra-articular conditions include labral tears, chondrocalcinosis, or osteochondral defects of the femoral head. These intra-articular conditions will be discussed in other areas of this book. This chapter will focus primarily on the extra-articular soft tissue conditions and their respective treatments.

to arthritic states due to cartilage degradation. Other intra-articular conditions include labral tears, chondrocalcinosis, or osteochondral defects of the femoral head. These intra-articular conditions will be discussed in other areas of this book. This chapter will focus primarily on the extra-articular soft tissue conditions and their respective treatments.

Neurologic Conditions

Nerve-compression syndromes occur throughout the body, and can similarly occur around the hip. These conditions typically occur where the nerve is tethered underneath a rigid soft tissue band, either fascial, ligamentous, or

tendinous. The two most common about the hip are piriformis syndrome and meralgia paresthetica.

tendinous. The two most common about the hip are piriformis syndrome and meralgia paresthetica.

Piriformis syndrome is a rare condition which occurs when the sciatic nerve is compressed under a tight, piriformis muscle tendon (3). It remains controversial as many believe that such symptoms may only arise as a result of spinal pathology. Patients may experience symptoms that mimic lumbar radiculopathy, including weakness and dysesthesias in the sciatic nerve distribution. The symptoms may be constant or intermittent, but are typically elicited with the leg in a flexed and internally rotated position, putting the piriformis tendon on stretch. Though it is far less common than lumbar disk pathology, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis, especially in the setting of a negative lumbosacral spine MRI. It is thus a diagnosis of exclusion when a workup of radicular symptoms is otherwise negative. Further diagnosis may be confirmed by EMG or nerve conduction studies. If confirmed, treatment may include surgical release of the piriformis tendon to relieve the entrapment on the nerve. This has been reported to be successful in up to 70% of patients who were able to return to precondition status in the early postoperative period (4).

Meralgia paresthetica is caused by compression of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. It was first described in 1977 (5) by Bellis, and further expanded anatomically by Edelson (6). It can occur idiopathically or postoperatively, and has been described after total hip replacement (THR), spine surgery, or other nonorthopedic surgical procedures (7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16). There has also been an association with morbid obesity (17). Treatment is generally self-limited but has been reported to respond to the relief of pressure from belts, topical analgesics, ultrasound-guided injections or

rarely surgical decompression (18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27). Other entrapment syndromes that have been described include obturator entrapment and superior gluteal nerve entrapment, both leading to subjective pain in their respective sensory distributions. Superior gluteal nerve entrapment may lead to abductor weakness with a Trendelenburg gait. Both are extremely rare (28,29). Nerve entrapment syndromes may be difficult to manage, requiring a longtime commitment from both the orthopedist and the patient for symptomatic resolution.

rarely surgical decompression (18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27). Other entrapment syndromes that have been described include obturator entrapment and superior gluteal nerve entrapment, both leading to subjective pain in their respective sensory distributions. Superior gluteal nerve entrapment may lead to abductor weakness with a Trendelenburg gait. Both are extremely rare (28,29). Nerve entrapment syndromes may be difficult to manage, requiring a longtime commitment from both the orthopedist and the patient for symptomatic resolution.

Trochanteric Bursitis

Pain over the lateral aspect of the greater trochanter may be a result of a variety of pathologic conditions, but the most common cause is trochanteric bursitis. Trochanteric bursitis occurs as a result of inflammation of the hip bursa, overlying the lateral aspect of the greater trochanter. Typically, the symptoms occur insidiously, over several weeks, with no antecedent trauma. Patients may report pain while lying on the affected side, at night; getting up out of a chair; or going up- or downstairs. Others may report an antalgic gait that worsens with fatigue. Symptoms can be temporarily improved with over-the-counter anti-inflammatory medications. The average age of onset is typically in the fourth to fifth decade though it can occur at any age (30,31).

Physical examination of trochanteric bursitis can be varied, though all patients generally have tenderness to palpation of the distal aspect of the greater trochanter. At times, the pain may radiate proximally toward the gluteus medius tendon, or more commonly distally, associated with a tight iliotibial band. This may be assessed with the Ober test (Fig. 43.5). A tight iliotibial band may, if not corrected, lead to continued pain and symptoms associated with bursitis.

Typically, trochanteric bursitis is a clinical diagnosis, and does not need to be imaged for visual confirmation. When the symptoms have been recurrent and unresponsive to typical treatments, further advanced imaging is sought to rule out other causes of hip pain, such as abductor tendon dysfunction or hip labral tears. Generally, patients are routinely screened with a radiograph, which may either be completely negative or show calcifications in the area of the bursitis (Fig. 43.6). Bone scan has been reported as a modality in the past (32), however, when symptoms persist, ultrasound or MRI may be helpful to confirm that no other associated conditions may be present such as gluteal muscle pathology or early-stage osteonecrosis (Figs. 43.7 and 43.8) (33).

Treatment is generally nonoperative. Care should be initiated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications unless otherwise contraindicated, often combined with physical therapy focused on inflammation, cryotherapy, stretching of the

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree