SLAP Lesions

Don’t sit in the saddle if you’re afraid of getting throwed.

Since their initial description by Snyder in the late 1980s, the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of superior labral tears (SLAP lesions) have been controversial. Furthermore, misdiagnosis and overtreatment of SLAP lesions, particularly in older individuals, have led to mixed results in the literature. Care must be taken to ensure that inappropriate surgical intervention is avoided, particularly in cases where a SLAP lesion is identified in passing.

The appropriate diagnosis of a SLAP lesion is based on clinical history, physical exam, and confirmatory arthroscopic findings. The classic patient is a young overhead athlete (age <30), with minimal daily symptoms but with disability while performing overhead athletics. Throwers often report pain when attempting to throw as well as inability to throw hard. This is known as the “dead arm syndrome.” Such patients will commonly have confirmatory physical exam findings (O’Driscoll sign, O’Brien sign, and reduction of pain with the Jobe relocation test) and classic arthroscopic findings of a SLAP lesion (see below). In addition, the absence of other pathology (e.g., full-thickness tears of the rotator cuff, chondromalacia, impingement) is further indicative that the SLAP lesion is the cause of the patient’s symptoms.

In patients over the age of 35, with an atraumatic onset of symptoms, generalized pain, which is worsened with overhead activities (not necessarily athletics), and other concomitant modifiers (worker’s compensation claim, litigation) or associated conditions (e.g., full-thickness tear of the rotator cuff), the diagnosis of a SLAP lesion should be guarded. While an anatomic SLAP lesion may exist on arthroscopic evaluation, many of these patients will have equivocal physical examination findings and the tear of the superior labrum may not be the cause of the symptoms. Other concomitant diagnoses should be considered (e.g., rotator cuff tear). We believe that patients over the age of 35 with an unstable biceps root may have a degenerative SLAP lesion. However, in these patients, SLAP repair is usually not indicated and one may choose to perform a biceps tenodesis if biceps tendinopathy is suspected.

ARTHROSCOPIC DIAGNOSIS

When a superior labral tear is suspected preoperatively, the superior labrum is carefully evaluated arthroscopically for injury. We base the arthroscopic diagnosis of a SLAP lesion on five specific findings:

In general, we require that three of these five characteristics must be present in order to definitively diagnose a SLAP lesion.

A drive-through sign occurs while viewing through a posterior portal when the arthroscope can be easily “driven” from the superior glenohumeral joint to the axillary recess with minimal resistance (Fig. 16.1). This is indicative of the pseudolaxity that may occur with SLAP lesions.

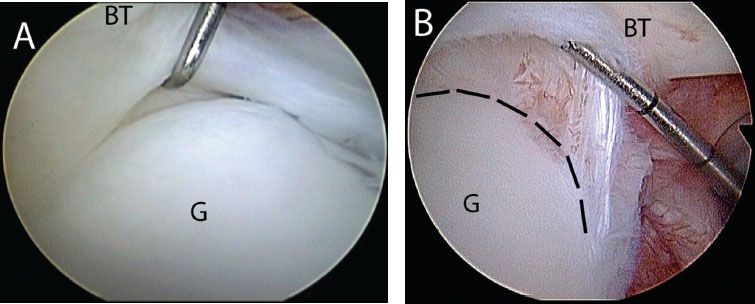

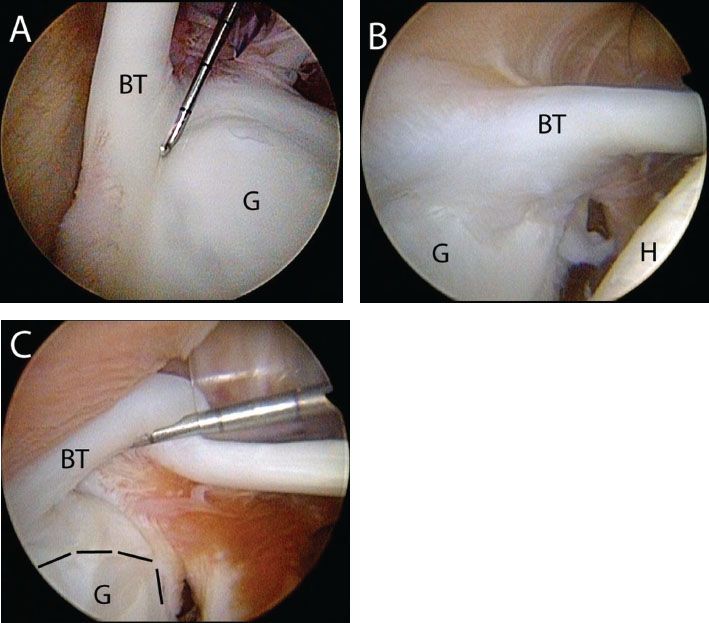

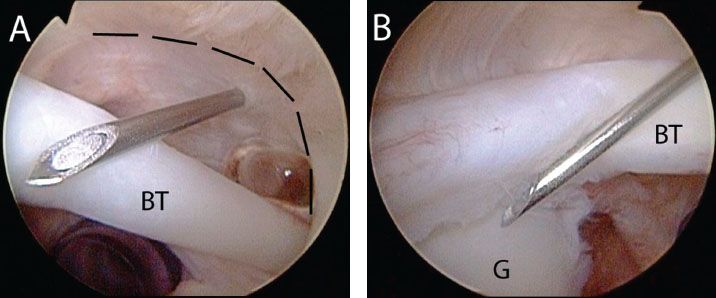

The width of the normal sublabral sulcus of the superior labrum ranges from approximately 3 to 5 mm and may increase with age. Therefore, if the width of the sublabral sulcus is increased and is associated with exposed bone (bare sublabral footprint), this is indicative of detachment of the superior labrum from the superior glenoid. Since the superior aspect of the glenoid under the labrum (the normal sublabral sulcus) is normally covered with articular cartilage (Fig. 16.2A), a bare sublabral footprint with exposed bone (further supported by associated undersurface labral fraying) is again indicative of detachment of the superior labrum from the glenoid (Fig. 16.2B). When this detachment is significant, stability of the biceps root may be affected and the root of the biceps may be easily translated medially with a probe (displaceable biceps root) (Fig. 16.3).

Figure 16.1 Right shoulder, anterosuperolateral viewing portal. The drive-through sign is demonstrated by an instrument that is easily passed from superior to inferior, with minimal resistance from the humeral head, in this patient with a SLAP lesion. G, glenoid; H, humerus.

Figure 16.2 Right shoulder, posterior viewing portal demonstrating (A) normal superior sublabral sulcus; (B) an abnormal sublabral recess >5 mm with exposed bone (glenoid rim outlined by dashed lines) BT, biceps tendon; G, glenoid.

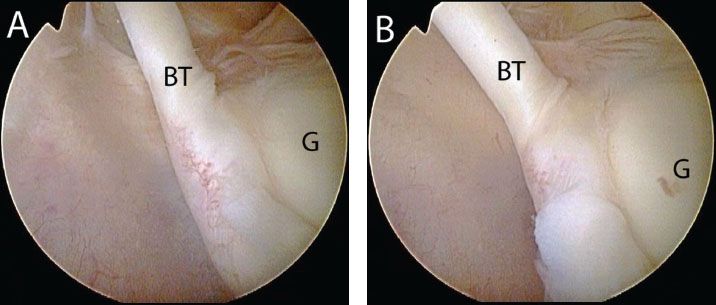

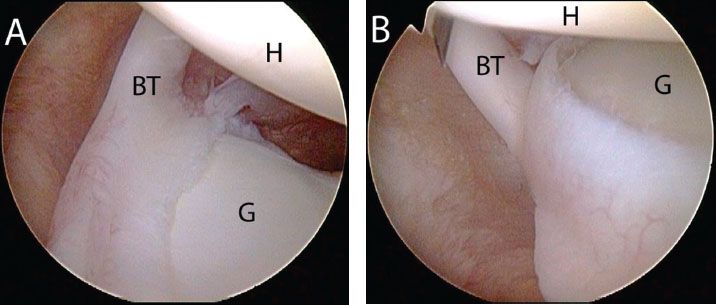

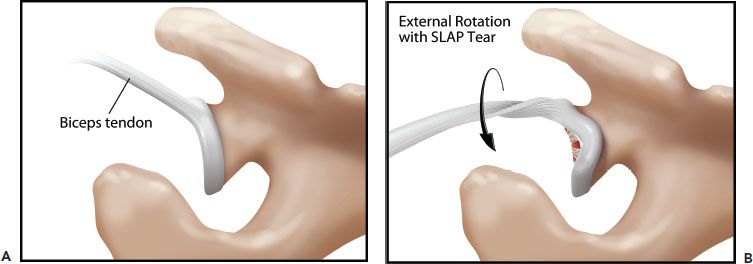

Finally, dynamic stability of the superior labrum and biceps root is evaluated by placing the arm in the functional throwing position of 90° of abduction and full external rotation. In patients with an intact superior labrum, the biceps root and superior labrum remain centered on the superior glenoid and the intra-articular portion of the biceps tendon merely changes its angular position relative to the superior labrum (Fig. 16.4). However, in patients with tears of the superior labrum (particularly if involving the posterior superior labrum), as the arm is brought into external rotation, the torsional force from the biceps tendon lifts the superior labrum off the glenoid and the labrum begins to “peel-back” off the glenoid, falling medially off the glenoid rim (Figs. 16.5 and 16.6). This is considered a positive peel-back sign and is indicative of an unstable superior labrum. Typically, a positive peel-back sign occurs in overhead athletes who have posterosuperior labral disruption in addition to disruption of the biceps root attachment into the bone. However, degenerative SLAP lesions usually do not display a positive peel-back sign.

INDICATIONS FOR REPAIR

In patients with an arthroscopic diagnosis of a SLAP lesion (i.e., satisfying three of the five criteria above), the decision to proceed with SLAP repair is largely based on the patient’s age, activity, and preoperative symptoms. In patients with the primary complaint of instability and associated Bankart or reverse Bankart lesions, a concomitant SLAP lesion is universally repaired to provide a stable base for labral repair and enhance stability. Furthermore, in young patients with difficulty with overhead sports, particularly in the absence of other major concomitant diagnoses, the SLAP lesion is repaired.

All other patients should be carefully reviewed for the preoperative suspicion of a SLAP lesion. In older patients where pain is the primary complaint, particularly in the presence of other concomitant diagnoses (e.g., rotator cuff tear), alternative treatment of the SLAP lesion may be indicated (e.g., biceps tenodesis or biceps tenotomy).

Figure 16.3 Probing the biceps root in right shoulder, posterior viewing portal. A: A probe reveals a stable biceps root. B: Right shoulder, posterior viewing portal. The biceps root appears normal initially, (C) but a probe reveals a displaceable biceps root. The glenoid rim is outlined by dashed lines. BT, biceps tendon; G, glenoid; H, humerus.

Figure 16.4 Right shoulder, posterior viewing portal demonstrates a negative peel-back (A) prior to peel-back maneuver; B: peel-back maneuver demonstrates an angle change of the biceps without displacement. BT, biceps tendon; G, glenoid.

Figure 16.5 Right shoulder, posterior viewing portal demonstrates a positive peel-back sign (A) prior to peel-back maneuver; B: peel-back maneuver results in medial displacement of the superior labrum and biceps root. BT, biceps tendon; G, glenoid; H, humerus.

TYPE II SLAP REPAIR (KNOTTED ANCHORS)

Standard posterior, anterior, and anterosuperolateral portals are established. However, in preparation for SLAP repair, it is important to create the anterior portal just superior to the lateral half of the subscapularis tendon to ensure a 45° of approach to the glenoid and adequate spacing for a second high anterior (anterosuperolateral) portal. Standard diagnostic arthroscopy is performed, evaluating for commonly associated lesions including partial-thickness rotator cuff tears or associated labral injuries (e.g., Bankart, reverse Bankart lesions). Pathology of the superior labrum is evaluated according to the criteria described above.

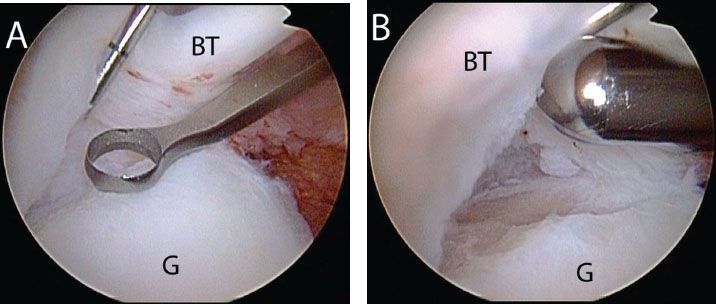

Once a SLAP lesion has been diagnosed, a separate anterosuperolateral portal is created just anterior to the supraspinatus tendon and directly above the biceps tendon to provide a 45° angle of approach to the superior glenoid rim (Fig. 16.7). This portal is usually 5 to 10 mm lateral to the anterolateral corner of the acromion. Through an anterior working portal, the superior glenoid neck is debrided with a shaver or ring curettes in order to remove any overlying cartilage and to create a bed of bare bone (Fig. 16.8). If the tear extends anteriorly or posteriorly, debridement from an anterosuperolateral portal may be necessary to gain access around the “corner” of the glenoid.

Figure 16.6 Schematic of the peel-back maneuver for demonstration of a superior labrum anterior and posterior (SLAP) tear. A: Appearance of the biceps root with the arm at the side. B: Placing the arm in 90° of abduction and maximal external rotation creates a torsional force on the biceps root. In the setting of a SLAP tear, the biceps root and the labrum just posterior to the biceps root displace medially during this maneuver.

Figure 16.7 Right shoulder, posterior viewing portal. A: An anterosuperolateral portal is established anterior to the supraspinatus ridge (outlined by dashed lines) with a spinal needle, and (B) provides a 45° angle of approach to the superior glenoid rim. BT, biceps tendon; G, glenoid.

Most SLAP lesions, particularly those with unstable biceps roots that display a positive peel-back sign, will require two anchors, one directly under the biceps root and one more posterior in the posterosuperior glenoid rim. Smaller lesions may require only one anchor, usually under the biceps root. The anterior anchor (3.0 mm Bio-Composite SutureTak, Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL) is placed first through the anterosuperolateral portal just at the articular bone junction (Fig. 16.9). Unlike Bankart or reverse Bankart lesions, creation of a “bumper” is not required and therefore reduction of the labrum to the articular junction is desirable for a “water tight” anatomic repair.

Although sutures may be passed directly in a retrograde fashion (Fig. 16.10), this technique can make a large hole through the labrum. Our current preference is to use a percutaneous shuttling technique with a small curved needle (Micro SutureLasso; Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL) through the labrum, passing simple sutures that encircle the labrum. If the superior glenohumeral ligament is avulsed, just anterior to the biceps, a separate anchor is used for its repair.

To pass a suture posterior to the long head of the biceps, a Micro SutureLasso is inserted percutaneously through a modified Neviaser portal piercing the labrum posterior to the biceps tendon (Fig. 16.11). The suture shuttle and the suture are then retrieved through the anterior or anterosuperolateral portal. It is important when placing these sutures not to incarcerate the biceps tendon. Sutures should be placed so that they secure the labrum, stabilizing the long head of the biceps tendon, but do not capture the tendon itself. Furthermore, in patients with cord-like middle glenohumeral ligaments or Buford complexes, it is important to avoid closing the anterior sulcus, as this can significantly restrict external rotation. The sutures are not tied until the posterior anchor is placed to avoid early binding of the soft tissue to bone which limits subsequent suture passage.

Figure 16.8 Right shoulder, posterior viewing portal. Preparation of bone bed for SLAP repair is accomplished with (A) a ring curette and (B) a shaver to expose an adequate bone bed for healing. BT, biceps tendon; G, glenoid.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree