CHAPTER 6 Skin and wound inspection and assessment

1. Differentiate between skin inspection and skin assessment.

2. List six factors to consider when assessing darkly pigmented skin.

3. Distinguish between wound assessment and evaluation of healing.

4. Define partial-thickness and full-thickness tissue loss.

5. Compare and contrast a normal and an abnormal finding for each wound assessment parameter.

6. Describe how to measure the length, width, depth, tunneling, and undermining of a wound.

Significance

In order to adequately convey the condition of a wound or a skin lesion, wound and skin assessment requires access to a unique vocabulary. As with monitoring blood pressure, temperature, and pulse rate, those attending to a wound preferably should use objective parameters to reflect its present status. However, the state of the science is such that both subjective and objective measures are required to adequately capture the condition of the wound. Because subjective measures by definition can vary in interpretation from one user to another, it is essential that accurate use of wound assessment terminology be emphasized in staff education and that competencies for wound and skin assessment be used (Appendix C).

The economics of health care impose additional motivation for conducting and documenting a systematic measurement of wound healing. Without objective criteria of the status or progress of repair, it is difficult to justify treatments or assign appropriate reimbursement for services. The standard of care is to provide accurate and routine skin and wound assessments. Failure to assess the patient systematically also carries a great legal liability risk (Murphy, 1996). Without accurate, consistent, and retrievable documentation, it is very difficult to retrospectively create a clear picture of the patient’s condition and of the care that actually was provided.

Assessment

The word assessment alone as it relates to the prevention and management of wounds can be confusing because a number of assessments are required: risk assessment (see Chapter 8), skin assessment, wound assessment, and physical assessment. For clarity and safety, findings from each type of assessment must be documented using appropriate terms to describe the patient’s skin or wound condition. Staff education should include how to conduct the assessments and how to link appropriate interventions to the findings.

Skin inspection and monitoring

When dressings are in place and do not require changing, the dressing should be monitored for intactness and the surrounding skin inspected for the presence or absence of discoloration (erythema, bruising), rash, break in skin integrity, and pain (van Rijswijk and Lyder, 2005). Narrative documentation can be as simple as “dressing dry and intact, surrounding skin within defined limits,” or a flow chart can be used (Appendix B).

Therefore, monitoring can occur independent of dressing change. However, if the dressing is leaking or new observations are made (swelling, pain, erythema), the dressing should be removed and a thorough wound assessment obtained. Monitoring usually occurs more frequently than an assessment or head-to-toe skin inspection, for example, every 8 hours in the acute care setting or every day in the long-term care setting. To conserve staff time and patient energy, monitoring and skin inspection can be conducted at the same time that other routine cares are provided (Table 6-1).

TABLE 6-1 Routine Activities Coordinated with Skin Inspection

| Routine Activity | Skin Inspection Site |

|---|---|

| Oxygen application | Back of ears and bridge of nose |

| Retaping or securing nasogastric tube | Nares |

| Tracheotomy care | Neck (under ties or strap) |

| Listening to lung sounds | Occiput, spinous process, scapula, coccyx, and sacrum |

| Listening to bowel sounds | Between and under skin folds of pannus and groin |

| Placing pillows under calves | Feet, heels, toes |

| Application or removal of antiembolism stockings or splints | Feet, heels, toes |

| Intravenous site care | Elbows and arms |

| Transferring in or out of chair | Coccyx and sacrum |

| Repositioning side to side | Feet, heels, toes, coccyx, sacrum, occiput, scapula, spinous process, trochanter |

Skin assessment

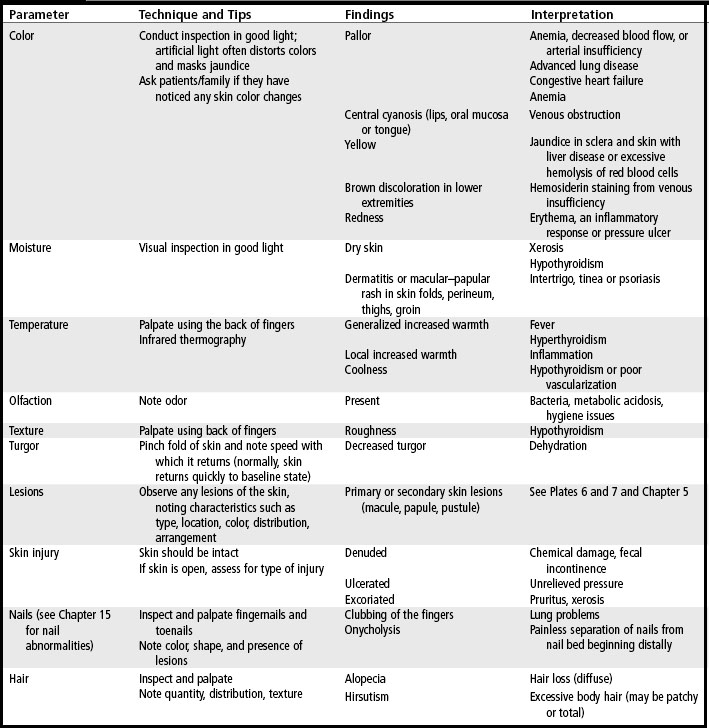

The standard of care is to conduct a routine and systematic skin assessment of all patients upon admission. Skin assessment parameters and deviations from normal are listed in Table 6-2. Examples and descriptions of lesions are presented in Chapter 5 (see Table 5-1 and Plates 6 and 7).

Skin assessments require good lighting for optimal visualization. Alterations including dry skin or xerosis should be noted. Skin palpation is used to assess skin temperature and texture in all patients but is of particular importance when assessing darkly pigmented skin. Skin with deviations from normal (e.g., firm to touch, boggy, pain, itching, warmth, coolness) should be compared with the adjacent skin or contralateral body part and documented (NPUAP and EPUAP, 2009).

Darker skin tones.

Health care in the United States and Europe has experienced a shift in racial and ethnic demographics, with black and Latino/Hispanic populations being the fastest growing among patients 85 years and older (ONS 2002; Salcido, 2002). Therefore accurate assessment of patients with darker skin pigmentation is an essential skill for all health care providers, and particularly wound care providers. The unique characteristics of darker versus lighter pigmented skin are summarized in Box 3-1. Teaching points and unique considerations when assessing darkly pigmented skin are provided in Checklist 6-1 (Bennett, 1995).

CHECKLIST 6-1 Assessing Pressure Ulcers on Darkly Pigmented Skin

✓ Color remains unchanged when pressure is applied.

✓ Color changes occur at site of pressure which differ from the patient’s usual skin color.

✓ Circumscribed area of intact skin may be warm to touch. As tissue changes color, intact skin will feel cool to touch. Note gloves may diminish sensitivity to changes in skin temperature.

✓ If patient previously had a pressure ulcer, that area of skin may be lighter than original color.

✓ Localized area of skin may be purple/blue or violet (eggplant) instead of red.

✓ Localized heat (inflammation) is detected by making comparisons to surrounding skin. Localized area of warmth eventually will be replaced by area of coolness, which is a sign of tissue devitalization.

✓ Edema (nonpitting swelling) may occur with induration and may appear taut and shiny.

✓ Patient complains of discomfort at a site that is predisposed to pressure ulcer development.

Unfortunately, detection and accurate identification of erythema and Stage I pressure ulcers with standard visual inspection are unreliable in persons with darkly pigmented skin (Bates-Jensen et al, 2009; Rosen et al, 2006; WOCN Society, 2010). This inability to detect and diagnose erythema in people with highly pigmented skin is evidenced by the incongruity between the prevalence of Stage I pressure ulcers in Caucasians (48%) versus African Americans (20%) (Baumgarten et al, 2004). Another study found that 32% of pressure ulcers detected in Caucasian residents were Stage I, whereas no Stage I pressure ulcers were detected in African American residents (Rosen et al, 2006).

A handheld dermal phase meter measuring subepidermal moisture has been studied in an attempt to identify early pressure ulcer damage (Bates-Jensen et al, 2009). Findings from a descriptive cohort study of 66 nursing home residents showed that subepidermal moisture provided a more accurate method of detecting early pressure ulcer damage than did visual assessment. If these findings are supported in larger studies, subepidermal moisture may emerge to be a useful clinical technique for detecting early damage in persons with darker skin tones.

Focused physical assessment

Healing is a phenomenon composed of multiple processes (see Chapter 4), each of which must function properly and sequentially. Whereas all patients require a physical assessment, the patient with a wound requires particular attention to systemic, psychosocial, and local factors that affect wound healing. A wound specialist is specifically educated to conduct this type of focused physical assessment and to interpret the results. The focused physical assessment should be obtained upon admission and with a change of condition. Components of a wound focused physical assessment are listed in Checklist 6-2.

CHECKLIST 6-2 Physical Assessment Parameters

Etiology and differential diagnosis.

Based on the wound-focused physical assessment, a differential diagnosis and likely etiology of the wound will be determined, which will drive intervention choices and treatment strategies. The completed physical assessment should help to exclude many possible etiologies for the wound but also will exclude treatment options. For example, compression is a critical intervention for successful management of the patient with venous insufficiency, but compression is contraindicated in the presence of arterial disease (see Chapter 11). Offloading is needed for management of a pressure ulcer (see Chapters 8 and 9), and glucose must be managed when the patient has diabetes (see Chapter 14). Wound etiology will also provide clues regarding the type of healing to anticipate. For example, a venous ulcer generally has little depth, so it often heals by epithelialization rather than wound contraction, which is in contrast to the deeper Stage III or IV pressure ulcer, which requires contraction for healing to occur. Measuring wound depth in the pressure ulcer clearly is an important piece of information but may be of little relevance in venous ulcers. Various types of skin damage are discussed in Chapter 5 and throughout this text. Interpretation of the data gathered through the focused physical assessment will guide the plan of care so that wound etiology and existing cofactors can be addressed.

Duration of wound and critical cofactors that impair healing.

A 4-week-old pressure ulcer that has not improved suggests the presence of cofactors that have not been adequately addressed, such as unresolved pressure, malnutrition, osteomyelitis, critical colonization, squamous cell cancer, or infection. Guidelines for pressure ulcers and arterial wounds recommend consideration of referral and biopsy for wounds that are unresponsive to 2 to 4 weeks of appropriate therapies (WOCN Society 2002, 2003).

Given a clear understanding of healing, these wounds must be considered out of synchronization and require reevaluation to identify factors that impede healing. Factors that impede healing are described in chapters throughout the text and listed in Checklist 6-2. Approaches used to assess systemic cofactors that affect wound healing along with the chapters that describe them in detail are listed in Table 6-3.

TABLE 6-3 Assessment of Cofactors

| Cofactor | Diagnostic Test | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue oxygenation | Transcutaneous oxygen | 28 |

| Bacterial load | Culture Biopsy | 16 |

| Circulation | Ankle–brachial index Toe–brachial index | 14 |

| Nutrition | Weight Body mass index Albumin Prealbumin Total lymphocyte count | 27 |

| Glycemic control | Blood glucose, hemoglobin A1c | 14 |

Wound assessment

Wound assessment is the collection of subjective data that characterize the status of the wound specifically as well as the periwound skin (see Plate 23). Parameters that compose a wound assessment are listed in Checklist 6-3 and described in this section. Conducting a wound assessment is a skill and requires precision and appropriate use of unique terms; use of appropriate terms is critically important. Therefore competency-based education for wound assessment is essential. Prior to assessment, the wound must be cleansed of loose debris, particulate matter, and dressing residue so that the normal architecture and color of the wound bed and surrounding skin can be fully appreciated.

CHECKLIST 6-3 Wound Assessment Parameters

Anatomic location.

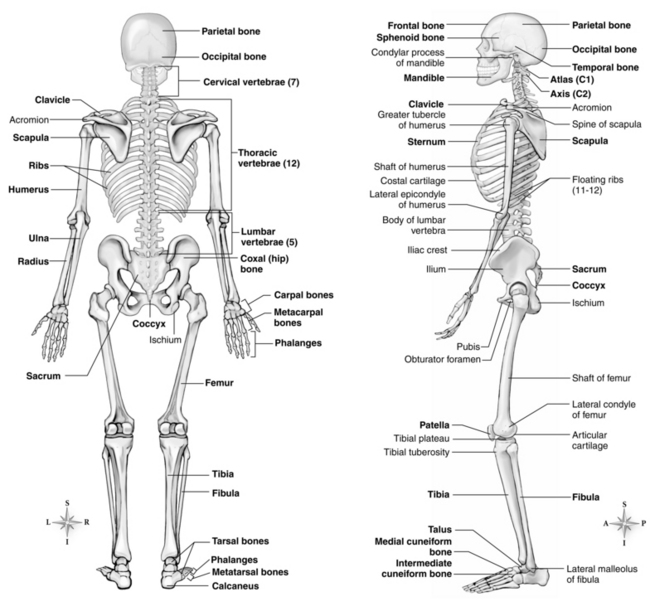

The anatomic location of the wound is important to record using proper terminology that will also provide clues about the etiology. Anatomic locations such as the sacrum and the coccyx must be clearly delineated (Figure 6-1). The location of a wound on the plantar surface of the foot can be accurately specified by terms such as metatarsal head. Anatomic location will also convey plan of care needs. For example, a wound on the ischial tuberosity should prompt caregivers to explore the patient’s sitting surface. A typical venous ulcer commonly appears on the medial aspect of the lower leg and will require compression. A patient with diabetes and a plantar surface foot ulcer typically has neuropathy and will need adequate blood glucose control and offloading.

Extent of tissue involvement.

Partial thickness and full thickness.

A partial-thickness wound is confined to the skin layers; damage does not penetrate below the dermis and may be limited to the epidermal layers only. These wounds heal primarily by reepithelialization (see Table 4-1 and Plate 1). A full-thickness wound indicates that the epidermis and dermis have been damaged into the subcutaneous tissue or beyond; tissue loss extends below the dermis (see Table 4-2 and Plates 2–5). Wound repair will occur by neovascularization, fibroplasia, contraction, and then epithelial migration from the wound edges. Partial thickness and full thickness can be used to describe most wounds but are not precise terms for specific types of tissue loss and depths of the wound. For example, a full-thickness wound can expose subcutaneous tissue, or it may extend to bone.

Classification systems.

Accurate classification requires knowledge of the anatomy of skin and deeper tissue layers, the ability to recognize these tissues, and the ability to differentiate between them. Classification systems for vascular and diabetic wounds assign a “grade” to the wound based on levels of tissue involvement, history of previous ulceration, presence of bony deformity, presence and severity of ischemia, and presence and severity of infection (Crawford and Fields-Varnado, 2004). Careful evaluation of the wound bed facilitates accurate classification, a complex skill that can take time to develop. Additional classification systems include skin tears (see Chapter 5), pressure ulcers (see Chapter 7), vascular wounds (see Chapter 11), diabetic wounds (see Chapter 14), and burns (see Chapter 32). However, as with all classification systems, these additional classification systems tell only a small part of the story and therefore should be used in conjunction with additional wound descriptors.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree