Orthopedic injuries are the leading cause of disability for the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps, resulting in between 22 and 63 % of all Physical Evaluation Board (PEB) cases in various services [2, 6]. Overall, between 1 and 2 % of all service members are evaluated annually for injury, with approximately 60 % of these resulting in discharge or permanent retirement from service [2]. Musculoskeletal disorders are on the rise in the Army specifically, with initial data from 1992 showing that they accounted for 30 % of all hospital admissions (28,000) and 40 % of all soldier noneffective days (over 500,000 days). Based on US Naval Medical Evaluation Board data between 1989 and 1993, of the top 10 diagnoses of injury leading to disability, shoulder dislocation was eighth overall, and was the top diagnosis not involving the lower extremity, accounting for 2.9 % of cases overall [6].

Shoulder problems are common among US military service members and shoulder pain is a frequent complaint among service members who present to health-care professionals, both in the primary care and tertiary specialty clinic settings. Walsworth et al. conducted a prospective descriptive analysis of patients presenting to a tertiary military medical treatment facility to better characterize the diagnoses of those who presented with a chief complaint of shoulder pain [7]. Of those who eventually underwent surgery, 84 % had more than one pathologic condition identified, with the three most common diagnoses including glenoid labrum injuries (80 %), impingement with rotator cuff disease (49 %), and instability (29 %) [7]. Seventy-six percent of patients were able to recall a specific mechanism of injury, with the top 3 mechanisms of injury reported, in order of prevalence, including overuse related to physical training/sports, trauma related to physical training/sports, and fall [7].

This study highlights the complexity of shoulder conditions encountered in US military service members, which commonly involve multiple structures (84 %), often have a prolonged duration of symptoms prior to presentation (average 33.75 months), and frequently have failed prolonged courses of nonoperative management prior to surgery (96 %) [7]. The frequency with which military patients attribute their conditions to a specific injury (76 %) is significantly higher than what has been described in civilian patients presenting to primary care settings, who have a reported mechanism of injury between 12 and 33 % of the time [8]. The increased rate of known injury further suggests the inherent occupational risks associated with the military profession and its associated upper extremity physical demands and requirements.

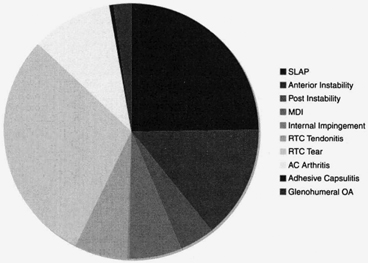

Provencher et al. further examined the young, active military population who presented to orthopedic surgeons with a complaint of shoulder dysfunction [9]. Two hundred seventy-five consecutive patients, with a mean age of 36.5 years, completed a battery of validated outcomes questionnaires at their initial presentation to gain a better understanding of the spectrum and severity of pathology present among military patients with shoulder complaints. Ten classes of presenting diagnoses are represented in Fig. 7.2 [9]. The investigators found that military patients presenting with shoulder complaints reported assessment scores approximately 50 % of normal, across all conditions, representing fairly poor function overall [9]. Patients with superior labrum anterior posterior (SLAP) tears demonstrated the lowest overall scores, reflecting the highest degree of dysfunction, followed by instability and rotator cuff tears. Not surprisingly, those military members who required surgery had uniformly lower scores than those who were successfully treated nonoperatively.

Fig. 7.2

Distribution of conditions in military patients presenting to orthopedic surgeons for shoulder pain [9]. SLAP superior labrum anterior posterior, MDI multidirectional instability, RTC rotator cuff, AC acromioclavicular, OA osteoarthritis

Combat Shoulder Wounds

As discussed in Chap. 3, disease and non-battle injuries (DNBIs) continue to be a leading cause of morbidity and disability among troops deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan for Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), respectively. Skeehan et al. conducted a recent epidemiological survey of deployed soldiers and found that 19.5 % of all soldiers reported at least one DNBI and 85 % sought care at least once during their deployment for symptoms [10]. The two most frequent causes of injury were sports/athletics and heavy gear lifting, with frequencies of 22.3 and 19.6 %, respectively [10]. Belmont et al. reported on the DNBIs sustained by a US Army Brigade Combat Team during a counterinsurgency campaign in OIF. They found that musculoskeletal injuries were the most frequent body system casualties and accounted for 50.4 % of all DNBIs [11]. Conditions related to the shoulder accounted for 11.8 % of all DNBIs during the study period, the fifth most common body region behind the hand, knee, ankle, and lumbar spine. First-time shoulder dislocation was the fourth most common injury overall, behind ankle sprain, anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture, and plantar fasciitis, with an incidence rate (IR) of 1.2 per 1000 soldier combat-years [11]. This compares similarly to previously reported IRs of 1.69 per 1000 person-years in the US Military as a whole and is approximately tenfold higher than the rates reported in civilian populations of between 0.11 and 0.24 per 1000 person-years [12, 13].

Roy recently examined another brigade combat team involved in operations in Afghanistan over a 15-month period in 2006–2007 to determine the prevalence of musculoskeletal diagnoses as well as mechanisms of injury in the deployed setting. This study better defined the at-risk nature of the military occupation in a deployed setting with regard to the shoulder. The shoulder was the fourth most frequently injured body region, affecting 164 of 1619 participants (10.1 %) [14]. When broken down by Military Occupational Specialty (MOS), shoulder injuries were most prevalent in engineers, at 12 % [14]. Engineers and maintenance personnel also had the highest percentage of shoulder impingement syndrome. This can be attributable to a number of factors, but likely represents the risk of overhead lifting combined with operating heavy equipment inherent within a military engineer’s profession. Interestingly, this study confirmed that engineers sustain more upper extremity injuries in the deployed setting at a rate of 25 % as compared to 15 % in the non-deployed engineer unit [14].

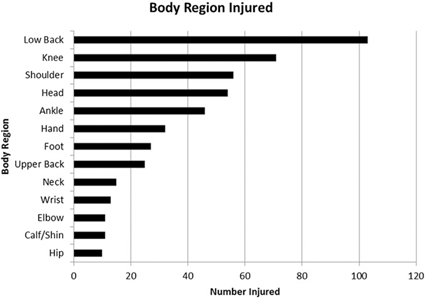

Risk factors for injury in the deployed setting have been examined. In one cohort of troops in Afghanistan, the shoulder was the third most common body region injured with an incidence of 10 %, with an overall average of 8.5 days of limited duty per injury (Fig. 7.3, [15]). The most frequent activities leading to injury included lifting and carrying (9.8 %), dismounted patrolling (9.6 %), and physical training (8.0 %) [15]. Specific risk factors associated with higher incidence of injury included older age, higher enlisted rank, female gender, higher duration of deployment in months, longer strength training sessions, heaviest load worn, and heavier or more frequent lifting tasks [15].

Fig. 7.3

Anatomical body regions injured most frequently during a 12-month deployment to Afghanistan [15]

Roy further examined the association between lifting tasks and injuries during the early portion (initial 3 months) of a Stryker Brigade Combat Team’s deployment to Afghanistan between July 2009 and July 2010. Soldiers reported working on average 6 days per week and wearing their armored vest and carrying additional load (totaling a mean of 47.7 lbs) for > 8 h/day [16]. Over 23 % of soldiers sustained an injury in the third month of deployment, with the shoulder the second most common anatomical region affected at 14.5 %. Gender, more days per week of lifting objects, and higher height of objects lifted were all significantly associated with injury [16].

Of the top 15 most frequently treated diagnoses encountered in the deployed setting, three involved the shoulder with impingement accounting for 3 % of all diagnoses, acromioclavicular (AC) separation 1.6 %, and pectoralis strain 0.7 % [14]. Three of the top five most common mechanisms of injury were overuse (22 %), weight lifting in the gym (8 %), and sports (8 %), which differ from the most common mechanisms of injury in the non-deployed setting of falls, vehicle accidents, and sports [1, 14]. With regard to shoulder-specific injuries, the incidence of shoulder injuries seen in Afghanistan (10.1 %) is lower than that reported from Iraq (17.0 %) [14, 17]. One postulated explanation for this discrepancy is related to the wear of the Deltoid Axillary Protector (DAP) augmentation to the personal Interceptor Body Armor (IBA) while in Iraq, yet not in Afghanistan. The DAP consists of two separate ambidextrous components—the deltoid protector and the axillary protector, which are added to the protective vest system. Given the frequency of overuse injuries and shoulder impingement syndrome, the additional weight and possible altered shoulder biomechanics from the DAP may have contributed to a higher prevalence of shoulder injuries. This potential negative effect of the DAP in relation to overuse injuries must be weighed against the reported potential benefits in preventing direct shoulder injuries related to blast and penetrating trauma. Gondusky et al. reported on the injury rates in one Marine Light Armored Reconnaissance Battalion during OIF while the unit was field-testing the shoulder and axillary protector, and reported an overall shoulder injury rate from blast and penetrating trauma of 5 % [18].

Owens et al. reviewed the Joint Theater Trauma Registry (JTTR) for all traumatic wounds sustained by US service members in OIF and OEF from October 2001 through January 2005, excluding DNBIs [19]. They found a total of 1566 soldiers sustained 6609 combat wounds, and of these, 1281 soldiers had sustained 3575 extremity combat wounds, with 53 % penetrating soft-tissue wounds and 26 % fractures [19]. The 915 fractures were evenly distributed between the upper (461, 50 %) and lower extremities (454, 50 %), with 45 (9.8 %) of the upper extremity fractures occurring in the clavicle (13) and scapula (32) [19]. Fifty-three percent of the clavicle fractures and 87 % of the scapula fractures were open [19]. Overall, the shoulder accounted for 5 % of all open fractures in OIF and OEF, which compares similarly to the only other conflict for which we have reported open shoulder fracture data—Operation Just Cause—with a 7 % incidence [19, 20].

Mack et al. also reviewed open periarticular shoulder fractures, reviewing one tertiary care treatment facility’s experience between March 2003 and January 2007 during OIF/OEF [21]. Reviewing 44 patients with open periarticular shoulder fractures, they found these to be extremely complicated injuries with high rates of associated neurologic (41 %), vascular (23 %), and other (86 %) injuries [21]. Forty-three percent of patients had a shoulder girdle injury with multiple fractures, with the top bones involved including the proximal humerus (66 %), acromion (36 %), glenoid (25 %), clavicle (23 %), and coracoid (18 %) [21]. Treatment challenges were highlighted by the high complication rates, with heterotopic ossification in 37 % of patients, postoperative deep infection/osteomyelitis in 14 %, nonfatal pulmonary embolus in 11 %, wound dehiscence in 6 %, and an overall amputation rate of 9 % [21].

Orthopedic injuries account for a significant proportion of long-term disability and subsequent discharge from military service in veterans injured during OIF and OEF. Army Physical Evaluation Board records of the 464 service members wounded between October 2001 and January 2005 reveal that 69 % of soldiers had unfitting orthopedic conditions [22]. Detailed descriptive analysis of combat-related orthopedic injuries by anatomic region in this population reveals that the shoulder alone accounts for 8 % of injuries, 10 % of disabling conditions, and an average percent disability for the service member of 23 %. [22].

Shoulder Girdle Injuries

Acromioclavicular Joint Sprains

Acromioclavicular (AC) joint injury is common among young athletes, and given the correlation in physical demands between competitive athletes and active-duty military personnel, it is also prevalent in the military population [23, 24]. AC joint injuries commonly occur in the third decade of life and have been reported to occur five times as often in males as compared to females in the civilian population [25]. However, data collected in a prospective, longitudinal cohort of US Military Academy cadets over a recent 4-year period show less of a discrepancy between the incidence in male and female cadets, with male patients only twice as likely to sustain an AC joint injury as females [24]. This is likely attributable to the younger mean age within this cohort, as well as the higher frequency of participation of females in higher risk intercollegiate athletic competition.

Pallis et al. reported an overall IR of 9.2 AC joint injuries per 1000 person-years in US Military Academy cadets [24]. The majority of these injuries (89 %) were classified as low-grade—type I or II according to the Rockwood classification system—with the vast majority of injuries (91 %) occurring as a result of participation in athletics [24, 25]. The distribution of injuries included AC sprains (87 %), fractures (7 %), sternoclavicular joint sprains (3 %), and inflammation/osteolysis (3 %). AC joint injuries resulted in an average of 18.4 days of duty lost per athlete, with low-grade injuries averaging 10.4 days versus high-grade injuries at 63.7 days per injury [24]. The IR of injury was significantly higher in intercollegiate athletes than intramural athletes, with an incidence rate ratio (IRR) of 2.11 [24]. The rate of surgical intervention was 19 times higher in high-grade injuries than low-grade injuries [24].

Clavicle Fractures

Clavicle fractures are one of the common injuries of the shoulder girdle both in the civilian and military populations, accounting for up to 5 % of all adult fractures and 35 % of shoulder girdle injuries in the general population [26, 27]. They hold a particular importance with respect to potential disability in military service members given their unique occupational demands. Military service members not only frequently perform high-risk overhead lifting and pulling activities but also participate in daily physical fitness training programs including push-ups and pull-ups, mandatory combatives training, obstacle courses, and frequently wear heavy shoulder-borne equipment such as rucksacks and individual body armor for extended periods of time [16, 24]. Injury to the shoulder girdle, including clavicle fractures, can render a soldier entirely incapable of performing these occupation-specific tasks for a period of time.

The trend in civilian trauma practice has moved toward operative management of displaced midshaft clavicle fractures to attempt to improve on the higher nonunion rates and poorer patient-centered outcomes scores associated with nonoperative management in these patients [26, 28, 29]. This trend is particularly applicable to the military population as well, given the specific occupational disability associated with painful midshaft clavicle fracture nonunions after nonoperative management in soldiers [30]. Huh et al. have challenged the notion that military patients cannot tolerate a plate on the clavicle due to the potential for symptomatic hardware, and shown promising early outcomes with plate fixation of midshaft clavicle fractures in a military cohort, with 93 % union rate at 3 months, 75 % patient satisfaction rate, and 79 % return of full shoulder motion [26]. They also reported on military-specific outcomes with 75 % able to do push-ups, 71 % able to wear body armor, 68 % able to wear a rucksack, and even in the short (6 month) study window, 21 % deployed after surgery [26].

Despite these promising results, others have challenged the notion of plate fixation in military patients. Wenninger et al. looked retrospectively at 62 patients undergoing surgical management of midshaft clavicle fractures and demonstrated a statistically higher complication rate in the plate fixation group (31 %) compared with the Hagie pin fixation group (9 %) [31]. The most common complication in both groups was symptomatic hardware and soft-tissue irritation, at an overall rate of 16 % [32].

Hsiao et al. queried the Defense Medical Epidemiology Database between 1999 and 2008 to determine the incidence of clavicle fractures in the US military and to identify any potential demographic risk factors for injury [33]. The authors reported a total of 12,514 clavicle fractures in an at-risk population with 13,770,767 person-years of follow-up, for an overall IR of 0.91 per 1000 person-years in the US Military [33]. Specific demographic variables that were significantly associated with increased incidence of clavicle fracture included sex, age, race, branch of service, and rank [33]. Men sustained clavicle fractures more than twice as often as females, with an IR of 0.67 per 1000 person-years in males compared to 0.29 for females. The adjusted IRR for men compared to women is 2.30 [33]. Clavicle fractures occurred significantly more often in white service members than both black service members and those listing “other” as their race. The adjusted IR for white service members is 0.66 per 1000 person-years, 0.49 for service members in the “other” category, and 0.27 for black service members. This leads to a greater than twofold increased risk for white service members as compared to black service members, with an adjusted IRR of 2.45 [33]. Rates of clavicle fractures generally decline with increasing age, with the peak incidence of injury occurring in the age groups of < 20 years and 20–24 years. Service members in the age groups < 20, 20–24, and 25–29 years had calculated IRs that were 38, 42, and 18 % higher, respectively, as compared to the > 40-year-old group [33]. With respect to branch of service, the highest IR was found in those serving in the Marine Corps, followed by those in the Army, Air Force, and Navy. With respect to the Navy—the lowest risk category— the Marine Corps, Army, and Air Force had IRs that were 44, 16 , and 6 % higher [33]. Military rank was also associated with the incidence of clavicle fracture, with the highest IR seen in the junior enlisted service members, followed in descending order by senior enlisted, junior officers, and senior officers. The IRs for junior enlisted, senior enlisted, and junior officers were 46, 35 and 12 % higher when compared to senior officers [33]. Overall, the IR of clavicle fractures is higher in the US military population (0.91 per 1000 person-years) than rates seen previously published for urban, civilian population which have ranged between 0.06 and 0.50 per 1000 person-years [27, 33, 34]. Demographic factors at highest risk in the military population are male gender, white race, and age less than 30 years [33].

Glenohumeral Joint Instability

Instability

Glenohumeral joint instability is a common orthopedic problem that can lead to pain and decreased ability to participate in physically demanding activities such as competitive athletics and military-specific occupational requirements [35]. Studies have evaluated a cohort of young, physically active military cadets at the US military Academy as well as the military population as a whole to determine the true incidence and characteristics of shoulder instability in the military population [13, 36]. Their findings highlight the importance of addressing this condition in the military, both from an initial management and treatment standpoint and a preventative standpoint by addressing modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors .

Several studies have reported on the incidence of shoulder dislocation in civilian populations. Simonet et al. estimated the incidence of primary, anterior shoulder dislocation to be 0.08 per 1000 person-years for the general population of Olmstead County, Minnesota [37]. European studies have estimated incidences of 0.17 per 1000 person-years in an urban population in Denmark, and 0.24 per 1000 person-years in a town in Sweden [21, 38].

In the largest US civilian population-based study of shoulder dislocations presenting to emergency departments, Zacchilli et al. reported an incidence of 0.24 per 1000 person-years [39]. In this study, utilizing the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System, the male IR was calculated as 0.35 per 1000 person-years, an IRR of 2.64 relative to females, with 71.8 % of all dislocations occurring in males [39]. When age was broken down by decade, the highest IR (0.48) occurred in those aged 20–29 years, with 46.8 % of all dislocations occurring in patients aged 15–29 years. There were no differences identified based on race in this cohort [39].

Owens et al. demonstrated in a closed population study among US military Academy cadets that the incidence of first-time traumatic shoulder dislocation is an order of magnitude greater in these military academy cadets than in previously reported studies [36]. The probability of a shoulder instability event (defined as a subluxation or dislocation) is 2.8 % per academic year, with an incidence proportion of 2.9 % for males and 2.5 % for females [36]. Overall, an IR of 4.35 per 1000 person-years was reported in this cohort [36]. The significantly higher IR in this study can be attributed both to the efficient methodology of data collection in a closed population as well as the younger age and higher activity level of these military cadets .

Of all instability events, 84.6 % were subluxations and 15.4 % were true glenohumeral dislocations, so when looking only at dislocation events, the incidence proportion is 0.43 % overall [36]. The majority of overall instability events were in the anterior direction (88 %), with 17 of 18 (94 %) of the dislocations occurring in the anterior direction [36]. This is consistent with previous reports of anterior dislocation rates of 97 % in the general population [38]. Mechanism of injury was recorded as well, showing that 43.6 % of instability events were a result of contact injuries and 41 % were from noncontact injuries [36]. High rates of intra-articular pathology were confirmed for both dislocations and subluxations. The high percentage of anterior dislocations with Bankart lesions (93 %) and Hill–Sachs lesions (86 %) in this military population is consistent with previous reports of Bankart tears and Hill–Sachs lesions in those who underwent surgery for instability, with rates of 97 and 90 %, respectively [36, 40]. Rates of pathologic lesions in the subluxation subset were reported for the first time, with incidences of Bankart lesions in 49 % and Hill–Sachs lesions in 48 % [36].

When evaluating the entire military population for shoulder dislocation, using the Defense Medical Epidemiology Database, the overall IR was calculated to be 1.69 dislocations per 1000 person-years [36]. Again, this is tenfold higher than rates of 0.08–0.24 per 1000 person-years previously reported in civilian population studies [12, 37, 38]. Significant independent risk factors for injury included male sex, white race, and age less than 30 years [13]. The calculated IR for males was 1.82 compared to 0.90 for females; and when controlling for race, age, branch of service, and rank, the adjusted IRR for males compared to females was reported as 1.95 [13]. Those service members with white race had an injury rate of 1.78 compared to 1.59 for “other” races and 1.41 for black race. The adjusted rate ratio for white race was 1.25 compared to black race [13]. Age also had a significant impact on injury rates, with increasing rates associated with the youngest age categories. The highest IR (2.35) occurred in the youngest age group (younger than 20 years old), yet all of the categories less than 30 years old had significantly greater risk than the older age groups [13]. With respect to branch of service, the highest IRs were seen in the Army (2.34) and marines (2.28) [13]. Finally, military rank played a significant role in risk for shoulder dislocation, with both junior and senior enlisted ranks having significantly higher rates than commissioned officers. Unadjusted IRs for junior enlisted, senior enlisted, and officers were 2.20, 1.32, and 1.12 per 1000 person-years, respectively [13].

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree