Shoulder Arthroscopy: The Basics

Elizabeth Matzkin

Craig R. Bottoni

DEFINITION

The shoulder is a spheroidal multiaxial joint stabilized not only by its bony anatomy but also by the surrounding muscles and capsular structures.

Arthroscopy is the process of visualization and examination of a joint using a fiberoptic instrument. All shoulder surgeons must be proficient in diagnostic arthroscopy of the shoulder.

ANATOMY

The glenohumeral joint consists of the glenoid fossa of the scapula that articulates with the head of the humerus.

The labrum is a “bumper” of fibrocartilaginous tissue around the rim of the glenoid that acts to deepen and enlarge the glenoid fossa and increase glenohumeral stability. The biceps tendon is anchored at the superior labrum and acts as a humeral head depressor and also aids in glenohumeral stability.

The static stabilizers of the shoulder include the joint capsule and the glenohumeral ligaments—superior, middle, and inferior glenohumeral ligaments. These will be discussed in greater detail in subsequent chapters.

The dynamic stabilizers of the shoulder are the rotator cuff muscles—supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis, and teres minor.

The scapular stabilizers—rhomboids, levator scapulae, trapezius, and serratus anterior—also contribute to dynamic stability of the shoulder.

PATHOGENESIS

Shoulder injuries can occur secondary to trauma, microtrauma, or overuse injuries and can be activity- and agedependent.

Most patients younger than age 40 years will have symptoms typical of overuse or instability, whereas patients older than age 40 years present more commonly with rotator cuff, impingement, inflammatory, or degenerative joint disease types of symptoms.

NATURAL HISTORY

Shoulder injuries can be painful and lead to shoulder dysfunction.

Recurrent shoulder instability decreases with age.2

The frequency of rotator cuff tears increases with age.1

If shoulder pathology is left unaddressed, pain, motion loss, degenerative changes, loss of function, and inability to participate in sports or work can occur.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The most important part of the physical examination consists of taking an accurate history from the patient.

Was it a traumatic, nontraumatic, or overuse injury?

When and how did the injury occur?

Is the patient’s complaint of pain, loss of motion, weakness, or inability to perform sports, activities of daily living, or work?

Is there pain at rest, only with activity, or while sleeping?

Are there any neurologic symptoms?

Basic physical examination methods are summarized in the following text. More specific examinations for different diagnoses will be described in other chapters in this section.

Observation of patient with shoulder pain from the front, back, and side

Identify any muscle atrophy and asymmetry of muscles, shoulder height, or scapular position.

Palpation of different parts of shoulder—sternoclavicular joint, acromioclavicular joint, greater tuberosity and rotator cuff, glenohumeral joint, biceps tendon, trapezium— to localize any areas of point tenderness, which may aid in differential diagnosis

Passive and active range of motion—forward flexion, abduction, adduction, internal and external rotation

Loss of range of motion may indicate adhesive capsulitis, rotator cuff pathology (tendinitis or rotator cuff tear), or degenerative changes.

Resistive testing of deltoid, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and subscapularis

Weakness of any muscles may indicate nerve injury, torn muscle or tendon, or weakness secondary to pain.

Rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers: Look for atrophy, scapular winging, weakness with strength testing, and painful range of motion.

Provocative tests for rotator cuff tear include drop arm sign and lift-off or belly press for subscapularis.

Impingement tests include the Neer and Hawkins tests.

Labrum: Catching, clicking, or popping may indicate a labral tear; check for instability with provocative tests (load shift, apprehension test or crank test, relocation, O’Brien test).

Multidirectional instability: Look for increased laxity inferiorly and in one other direction.

The sulcus sign demonstrates inferior laxity.

Check for the ability to voluntarily subluxate or dislocate the humeral head.

Acromioclavicular joint: localized tenderness over the acromioclavicular joint and pain with cross-chest adduction and O’Brien testing

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographs are used to assess different aspects of the shoulder joint.

Basic radiographs should consist of anteroposterior, axillary, and outlet views.

Special views may be obtained depending on shoulder pathology and will be discussed in subsequent chapters.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and MRI arthrograms are also commonly obtained to aid in diagnosis because they are highly sensitive and specific in diagnosing many shoulder injuries.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Impingement (internal or external)

Rotator cuff tear

Adhesive capsulitis

Acromioclavicular joint injury or arthritis

Labral tear

Instability

Biceps tendon pathology

Degenerative arthritis

Scapulothoracic dysfunction

Cervical or neurologic

Infection

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative management for many different diagnoses may first consist of rest, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, physical therapy, and diagnostic and therapeutic injections.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

A patient who has failed to respond to nonoperative management and continues to have symptoms consistent with his or her diagnosis is a candidate for shoulder arthroscopy.

Preoperative Planning

Patient history and imaging studies are reviewed.

The surgeon should have a good understanding of what pathology to expect at the time of arthroscopy to ensure that all appropriate equipment and instruments are available.

Patient positioning aids (arm holders, weights, beanbag, axillary roll)

Arthroscopic pumps or irrigation system

Video monitor, 30- and 70-degree arthroscopes

Arthroscopic cannulas

Shavers, burrs, suture anchors, arthroscopic instruments (probe, grasper, scissor, basket)

An examination under anesthesia is performed to assess range of motion and stability.

Positioning

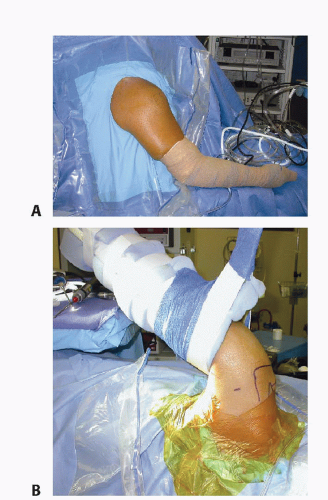

Shoulder arthroscopy may be performed with the patient in either a beach-chair position or the lateral decubitus position (FIG 1).

The beach-chair position requires a specially designed operating table attachment that ensures that the surgeon has adequate exposure to the patient’s posterior shoulder and the patient’s head is well supported.

The advantage of this position is that the shoulder can be freely manipulated throughout the procedure.

Commercially available arm holders can also be used to allow glenohumeral distraction and positioning without the need for an assistant.

When using the lateral decubitus position (FIG 1B), the patient must be properly padded and the body supported with a beanbag, axillary roll, and pillows.

The operative extremity is placed in a commercially available arm holder in approximately 70 degrees of abduction and 15 to 20 degrees of forward flexion, with 10 pounds of weight for traction. This allows for distraction of the glenohumeral joint and offers excellent visualization.

Approach

The operating room should be set up to allow the surgeon easy access to the entire shoulder and permit optimal visualization of the video monitors and arthroscopic equipment.

The typical operating room setup is shown in FIG 2.

The entire shoulder, arm, forearm, and hand and the exposed portion of the patient’s hemithorax should be sterilely prepared after isolation with a clear U-drape. This will aid in keeping the patient dry in case fluid leaks under the surgical drapes.

TECHNIQUES

▪ Setup and Portal Placement

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree