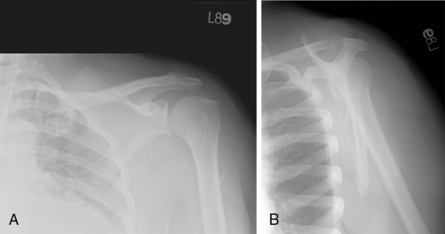

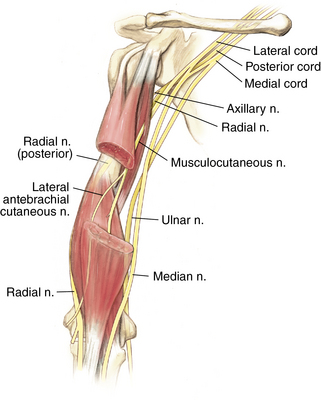

2 Shoulder and humerus Figure 2-8. Major branches of the brachial plexus in the upper arm. (From Miller MD, Chhabra AB, Hurwitz SR, et al, editors: Orthopaedic surgical approaches, Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders, p 17.) Inspect for deformity or muscle atrophy. Palpate the specific structures to evaluate for deformity or tenderness: Normal range of motion (ROM): Table 2-1 Table 2-1. Normal Shoulder Range of Motion Table 2-2. • Pain medication refill, if necessary • Discontinuation of sling as tolerated • Review of work status, light duty desk work generally for 6 weeks • These patients are significantly weak on examination and may demonstrate a drop arm sign. • Diagnosis can be made by plain radiographs when proximal migration of the humeral head relative to the glenoid is seen (Fig. 2-14). • Physical therapy orders given to focus on passive ROM of the shoulder only • Pain medication refill, if necessary • Continued use of sling removing only for pendulum exercises and elbow motion • Review of work status; light duty desk work begun as tolerated by patient, with no use of surgical arm • Evaluation of wound healing, ROM, and strength • New physical therapy orders to begin active-assisted ROM, active motion, and gentle early rotator cuff strengthening exercises • Light duty work continued for a minimum of 6 additional weeks

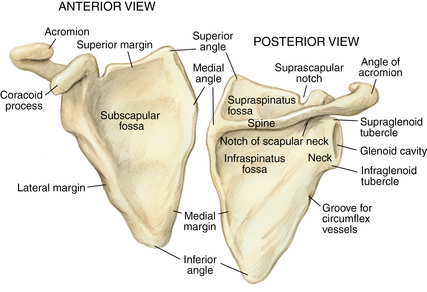

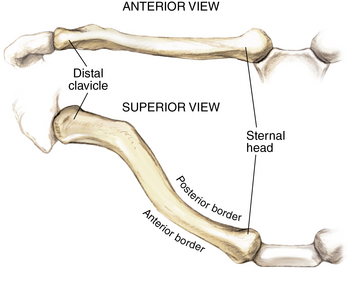

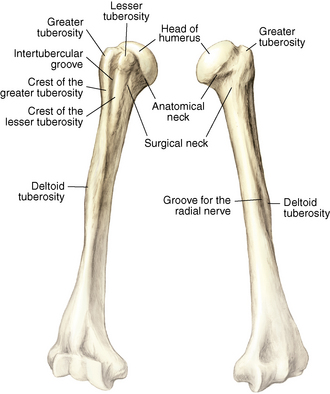

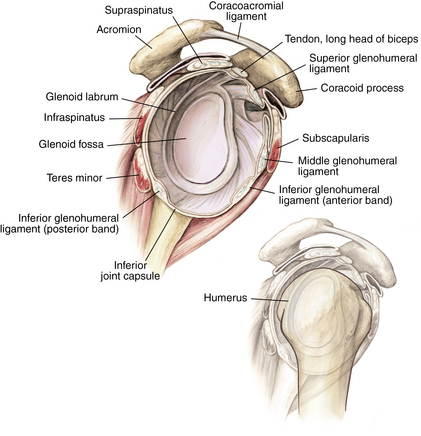

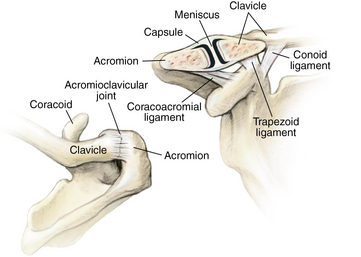

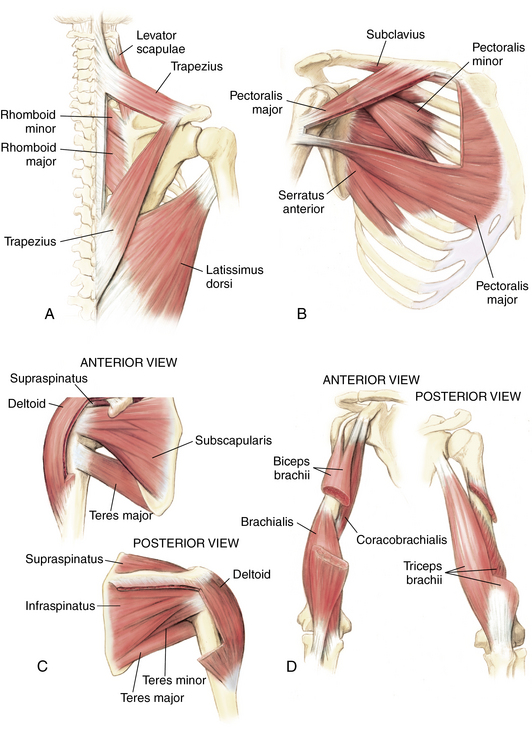

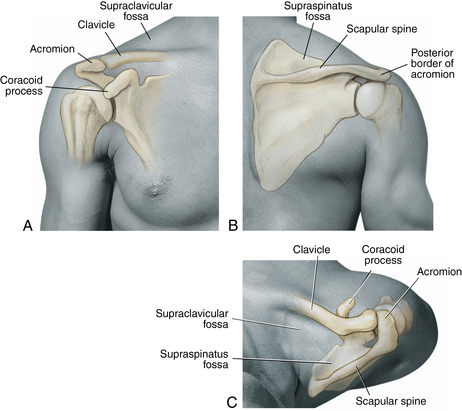

Anatomy of joint

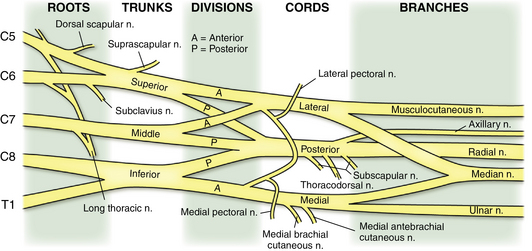

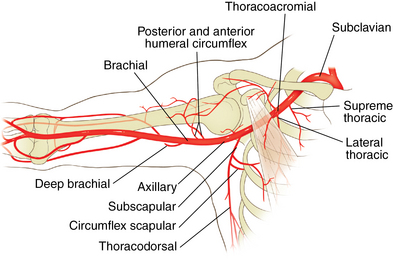

Nerves and arteries: Figures 2-7 through 2-9

Physical examination

Forward Flexion

180 degrees

Abduction

180 degrees

External Rotation

90 degrees

Internal Rotation

90 degrees

Special tests

Belly press test

Tests for rotator cuff tear (subscapularis); alternative to lift-off test for patients unable to position their arm behind their back

Tests for rotator cuff tear (subscapularis); alternative to lift-off test for patients unable to position their arm behind their back

Performed by asking the patient to use the heel of the hand and press it into his or her abdomen while holding the elbow forward

Performed by asking the patient to use the heel of the hand and press it into his or her abdomen while holding the elbow forward

Positive test indicated by an inability to hold the elbow forward, thus allowing it to drift back to the side

Positive test indicated by an inability to hold the elbow forward, thus allowing it to drift back to the side

Apprehension test

Tests for shoulder instability (anterior)

Tests for shoulder instability (anterior)

Performed by asking the patient to lie supine while the examiner passively moves the shoulder into an abducted and externally rotated position

Performed by asking the patient to lie supine while the examiner passively moves the shoulder into an abducted and externally rotated position

Positive test indicated by “apprehension” on the part of the patient as he or she feels the shoulder slide anteriorly

Positive test indicated by “apprehension” on the part of the patient as he or she feels the shoulder slide anteriorly

O’brien test

Tests for superior labrum anterior to posterior (SLAP) tear

Tests for superior labrum anterior to posterior (SLAP) tear

Performed by having the patient hold the arm in 90 degrees of forward flexion and 10 to 20 degrees of adduction with the thumb down then resisting a downward force to the arm applied by the examiner; test repeated with the thumb up

Performed by having the patient hold the arm in 90 degrees of forward flexion and 10 to 20 degrees of adduction with the thumb down then resisting a downward force to the arm applied by the examiner; test repeated with the thumb up

Positive test indicated by pain, which should be worse with the “thumb down” position; if pain present also in the “thumb up” position, may indicate an AC joint problem

Positive test indicated by pain, which should be worse with the “thumb down” position; if pain present also in the “thumb up” position, may indicate an AC joint problem

Differential diagnosis: Table 2-2

Anterior shoulder pain

Shoulder impingement

Biceps tendinitis

Arthritis

Rotator cuff tear

Instability

Labral tear

Posterior shoulder pain

Periscapular muscle pain

Posterior instability

Cervical radiculopathy

Posterior labral tear

Subscapular bursitis

Scapula fracture

Superior shoulder pain

Acromioclavicular joint osteolysis

Acromioclavicular joint arthritis

Clavicle fracture

Shoulder (AC) separation

Superior labral tear

Arm pain

Humerus fracture

Rotator cuff tear

Shoulder impingement

Cervical radiculopathy

Shoulder impingement

Initial treatment

Shoulder impingement is part of the spectrum of rotator cuff injury. Generally, in the early stages this involves inflammation (bursitis and rotator cuff tendinitis) without actual tearing of the tendon. Partial tears can develop over time and can progress to a full-thickness tear. If symptoms do not improve with early treatment, call the office because a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan may be necessary to evaluate for a rotator cuff tear.

Shoulder impingement is part of the spectrum of rotator cuff injury. Generally, in the early stages this involves inflammation (bursitis and rotator cuff tendinitis) without actual tearing of the tendon. Partial tears can develop over time and can progress to a full-thickness tear. If symptoms do not improve with early treatment, call the office because a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan may be necessary to evaluate for a rotator cuff tear.

First treatment steps

Begin general antiinflammatory measures including nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), ice, and activity modification.

Begin general antiinflammatory measures including nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), ice, and activity modification.

Perform subacromial steroid injection.

Perform subacromial steroid injection.

Begin physical therapy that emphasizes rotator cuff strengthening exercises.

Begin physical therapy that emphasizes rotator cuff strengthening exercises.

If symptoms persist despite injection and physical therapy, consider ordering an MRI scan with an arthrogram of the shoulder to evaluate the integrity of the rotator cuff.

If symptoms persist despite injection and physical therapy, consider ordering an MRI scan with an arthrogram of the shoulder to evaluate the integrity of the rotator cuff.

Use of a sling is generally discouraged because this can lead to shoulder stiffness and adhesive capsulitis.

Use of a sling is generally discouraged because this can lead to shoulder stiffness and adhesive capsulitis.

Treatment options

Nonoperative management is indicated if the patient has pain without evidence of a full-thickness rotator cuff tear (night pain, weakness on examination, history of recent shoulder dislocation in patient over the age of 40 years).

Nonoperative management is indicated if the patient has pain without evidence of a full-thickness rotator cuff tear (night pain, weakness on examination, history of recent shoulder dislocation in patient over the age of 40 years).

Treatment generally begins with the addition of NSAIDs and/or subacromial steroid injection.

Treatment generally begins with the addition of NSAIDs and/or subacromial steroid injection.

Physical therapy and/or a home program with Thera-Bands should be started to focus on rotator cuff strengthening.

Physical therapy and/or a home program with Thera-Bands should be started to focus on rotator cuff strengthening.

Work restrictions may be necessary if the patient has a job that involves repetitive activity or overhead reaching with the affected arm, to prevent repeat aggravation of the inflammation.

Work restrictions may be necessary if the patient has a job that involves repetitive activity or overhead reaching with the affected arm, to prevent repeat aggravation of the inflammation.

Prognosis for shoulder impingement is good with these nonsurgical treatment options.

Prognosis for shoulder impingement is good with these nonsurgical treatment options.

Generally the patient should be reevaluated in 6 weeks to check ROM and strength.

Generally the patient should be reevaluated in 6 weeks to check ROM and strength.

Failure to improve at that point may warrant further evaluation of rotator cuff integrity with an MRI arthrogram.

Failure to improve at that point may warrant further evaluation of rotator cuff integrity with an MRI arthrogram.

Generally, failure to improve with one to two subacromial injections and a minimum of 6 weeks of physical therapy should prompt referral to a surgeon to consider surgical options for shoulder impingement.

Generally, failure to improve with one to two subacromial injections and a minimum of 6 weeks of physical therapy should prompt referral to a surgeon to consider surgical options for shoulder impingement.

Operative management: Subacromial decompression

Codes

Informed consent and counseling

Routine surgical risks should be discussed with the patient (infection, bleeding, bruising, surgical pain, continued symptoms, and anesthesia complications).

Routine surgical risks should be discussed with the patient (infection, bleeding, bruising, surgical pain, continued symptoms, and anesthesia complications).

If your institution routinely uses nerve blocks as part of postoperative pain management, the expected duration of action of these blocks should be discussed.

If your institution routinely uses nerve blocks as part of postoperative pain management, the expected duration of action of these blocks should be discussed.

Generally, the patient is expected to be in a sling for up to 2 weeks, and use of the sling is discontinued based on patient comfort.

Generally, the patient is expected to be in a sling for up to 2 weeks, and use of the sling is discontinued based on patient comfort.

Physical therapy is generally expected after surgery for approximately 6 weeks.

Physical therapy is generally expected after surgery for approximately 6 weeks.

Informed consent should include the possibility of rotator cuff repair if an unexpected tear is discovered at the time of surgery because this could lead to a longer recovery time (6 weeks in a sling and an average of 12 weeks of physical therapy).

Informed consent should include the possibility of rotator cuff repair if an unexpected tear is discovered at the time of surgery because this could lead to a longer recovery time (6 weeks in a sling and an average of 12 weeks of physical therapy).

Surgical procedures

The posterior portal is first created as the primary viewing portal for the arthroscope, followed by the anterior portal (working portal) for instruments.

The posterior portal is first created as the primary viewing portal for the arthroscope, followed by the anterior portal (working portal) for instruments.

Diagnostic arthroscopy should be performed before the initiation of any procedure, with careful evaluation of the glenohumeral joint, labrum, biceps tendon, rotator cuff, and joint capsule.

Diagnostic arthroscopy should be performed before the initiation of any procedure, with careful evaluation of the glenohumeral joint, labrum, biceps tendon, rotator cuff, and joint capsule.

Placing the camera in the posterior portal and directing it superiorly allows visualization of the subacromial space.

Placing the camera in the posterior portal and directing it superiorly allows visualization of the subacromial space.

A lateral portal can be made to pass instruments for the acromioplasty.

A lateral portal can be made to pass instruments for the acromioplasty.

Electrocautery or radiofrequency devices may be superior to routine arthroscopic shavers because they help to control bleeding as the highly vascular bursa is débrided.

Electrocautery or radiofrequency devices may be superior to routine arthroscopic shavers because they help to control bleeding as the highly vascular bursa is débrided.

After the bursa is adequately débrided, the coracoacromial ligament is cut, and an arthroscopic bur is used to remove impinging bone from the inferior surface of the acromion.

After the bursa is adequately débrided, the coracoacromial ligament is cut, and an arthroscopic bur is used to remove impinging bone from the inferior surface of the acromion.

Adequate bony resection should be confirmed before removing the arthroscope and closing the portals.

Adequate bony resection should be confirmed before removing the arthroscope and closing the portals.

Estimated postoperative course

Initial postoperative visit (7 to 14 days)

Initial postoperative visit (7 to 14 days)

12-week postoperative visit (optional)

12-week postoperative visit (optional)

Rotator cuff tears

Pain is located in the anterior and lateral shoulder.

Pain is located in the anterior and lateral shoulder.

Pain frequently radiates to the deltoid area, but not usually below elbow.

Pain frequently radiates to the deltoid area, but not usually below elbow.

Tears are generally atraumatic, with progression of pain and weakness over time.

Tears are generally atraumatic, with progression of pain and weakness over time.

They may be related to an acute trauma (e.g., fall on the outstretched hand).

They may be related to an acute trauma (e.g., fall on the outstretched hand).

Waking at night is one of the frequently described symptoms.

Waking at night is one of the frequently described symptoms.

The patient may or may not complain of weakness in that arm.

The patient may or may not complain of weakness in that arm.

Physical examination

Active ROM may be limited, but passive ROM is generally full.

Active ROM may be limited, but passive ROM is generally full.

Hawkins and Neer impingement signs may or may not be present.

Hawkins and Neer impingement signs may or may not be present.

The drop arm sign (inability to hold the arm in an abducted position against gravity) indicates a likely massive rotator cuff tear.

The drop arm sign (inability to hold the arm in an abducted position against gravity) indicates a likely massive rotator cuff tear.

The supraspinatus stress test (weak with resisted abduction) is positive.

The supraspinatus stress test (weak with resisted abduction) is positive.

Weakness with resisted external rotation indicates involvement of the infraspinatus.

Weakness with resisted external rotation indicates involvement of the infraspinatus.

A positive lift-off or belly press sign indicates involvement of the subscapularis.

A positive lift-off or belly press sign indicates involvement of the subscapularis.

A positive O’Brien sign indicates involvement of the biceps tendon.

A positive O’Brien sign indicates involvement of the biceps tendon.

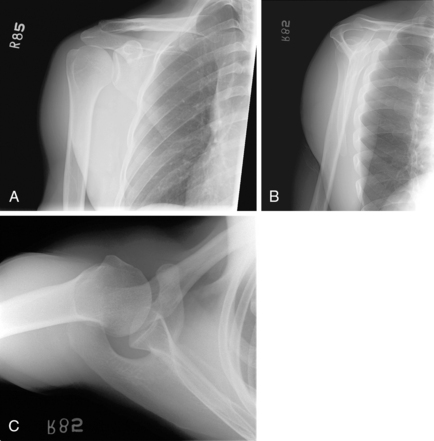

Imaging

Plain radiography should include AP, axillary, and outlet views.

Plain radiography should include AP, axillary, and outlet views.

An MRI scan with arthrogram is the “gold standard” for diagnosing and evaluating the extent of rotator cuff disease (Fig. 2-13).

An MRI scan with arthrogram is the “gold standard” for diagnosing and evaluating the extent of rotator cuff disease (Fig. 2-13).

A computed tomography (CT) arthrogram may be necessary for patients who are unable to undergo MRI (e.g., patients with a pacemaker).

A computed tomography (CT) arthrogram may be necessary for patients who are unable to undergo MRI (e.g., patients with a pacemaker).

Classification system

Rotator cuff tears are typically described by the number of tendons involved, the size of the tear, the amount of tendon retraction, and the degree of fatty atrophy of the rotator cuff muscles.

Rotator cuff tears are typically described by the number of tendons involved, the size of the tear, the amount of tendon retraction, and the degree of fatty atrophy of the rotator cuff muscles.

Partial tears are commonly seen in patients who are more than 40 years old and may or may not be symptomatic. It is helpful to determine the percentage of involved tendon with MRI to determine treatment.

Partial tears are commonly seen in patients who are more than 40 years old and may or may not be symptomatic. It is helpful to determine the percentage of involved tendon with MRI to determine treatment.

Complete rotator cuff tears should be described by the number of involved tendons and the amount of retraction.

Complete rotator cuff tears should be described by the number of involved tendons and the amount of retraction.

Massive tears are generally defined as those involving two or more tendons and retracted more than 5 cm.

Massive tears are generally defined as those involving two or more tendons and retracted more than 5 cm.

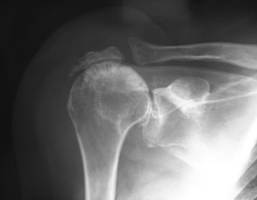

Rotator cuff arthropathy denotes massive, retracted, chronic rotator cuff tears that are generally considered irreparable.

Rotator cuff arthropathy denotes massive, retracted, chronic rotator cuff tears that are generally considered irreparable.

At the time of arthroscopy, rotator cuff tears can further be described by the shape of the tear (e.g., U-shaped tear).

At the time of arthroscopy, rotator cuff tears can further be described by the shape of the tear (e.g., U-shaped tear).

Initial treatment

Initial treatment is determined by the size of the rotator cuff tear.

Initial treatment is determined by the size of the rotator cuff tear.

Partial rotator cuff tears involving less than 50% of the total tendon area may respond well to conservative treatment including NSAIDs, subacromial steroid injections, and physical therapy.

Partial rotator cuff tears involving less than 50% of the total tendon area may respond well to conservative treatment including NSAIDs, subacromial steroid injections, and physical therapy.

High-grade partial rotator cuff tears (involving >50% of the total tendon area) may be treated conservatively but may require surgical repair. This decision is determined by the degree of the patient’s pain and dysfunction and the severity of the tear (for a 60% tear, an attempt at conservative treatment is more likely, whereas a 90% tear may suggest the need for earlier operative intervention).

High-grade partial rotator cuff tears (involving >50% of the total tendon area) may be treated conservatively but may require surgical repair. This decision is determined by the degree of the patient’s pain and dysfunction and the severity of the tear (for a 60% tear, an attempt at conservative treatment is more likely, whereas a 90% tear may suggest the need for earlier operative intervention).

Complete rotator cuff repairs should be treated with surgery in most cases.

Complete rotator cuff repairs should be treated with surgery in most cases.

Patient education

Rotator cuff tears occur as a spectrum of injury ranging from tendinitis to partial tearing to complete tear to irreparable tear.

Rotator cuff tears occur as a spectrum of injury ranging from tendinitis to partial tearing to complete tear to irreparable tear.

Complete tears of the rotator cuff require surgery to repair the tendon.

Complete tears of the rotator cuff require surgery to repair the tendon.

Patients should use the shoulder normally to maintain ROM but avoid repetitive overhead activities and heavy lifting.

Patients should use the shoulder normally to maintain ROM but avoid repetitive overhead activities and heavy lifting.

First treatment steps

Complete rotator cuff tears should be referred to a shoulder surgeon.

Complete rotator cuff tears should be referred to a shoulder surgeon.

Although surgical treatment is not urgent, ideally surgery occurs in the first 1 to 3 months of diagnosis because of the risk of tendon retraction with longer delays.

Although surgical treatment is not urgent, ideally surgery occurs in the first 1 to 3 months of diagnosis because of the risk of tendon retraction with longer delays.

The use of a sling should be avoided because this can lead to the development of adhesive capsulitis.

The use of a sling should be avoided because this can lead to the development of adhesive capsulitis.

Treatment options

Nonoperative management typically is reserved for partial, low-grade rotator cuff tears.

Nonoperative management typically is reserved for partial, low-grade rotator cuff tears.

NSAIDs, subacromial steroid injections, and physical therapy effective in managing pain and improving function.

NSAIDs, subacromial steroid injections, and physical therapy effective in managing pain and improving function.

Patients should be instructed to follow up for a new evaluation if conservative treatment does not improve symptoms in 6 to 8 weeks.

Patients should be instructed to follow up for a new evaluation if conservative treatment does not improve symptoms in 6 to 8 weeks.

MRI arthrogram, if not already performed, may be necessary at that point to evaluate for a full-thickness rotator cuff tear.

MRI arthrogram, if not already performed, may be necessary at that point to evaluate for a full-thickness rotator cuff tear.

Operative management: Rotator cuff repair

Informed consent and counseling

Routine surgical risks should be discussed with the patient (infection, bleeding, bruising, surgical pain, continued symptoms, and anesthesia complications).

Routine surgical risks should be discussed with the patient (infection, bleeding, bruising, surgical pain, continued symptoms, and anesthesia complications).

If your institution routinely uses nerve blocks as part of the postoperative pain management, the expected duration of action of these blocks should be discussed.

If your institution routinely uses nerve blocks as part of the postoperative pain management, the expected duration of action of these blocks should be discussed.

Generally, the patient is expected to be in a sling for approximately 6 weeks postoperatively.

Generally, the patient is expected to be in a sling for approximately 6 weeks postoperatively.

Physical therapy is generally started after the first postoperative appointment and continued for 12 weeks.

Physical therapy is generally started after the first postoperative appointment and continued for 12 weeks.

Surgical procedures

Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair

Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair

Open rotator cuff repair (may be used based on the surgeon’s experience or because of massive tears in which adequate repair cannot be obtained arthroscopically)

Open rotator cuff repair (may be used based on the surgeon’s experience or because of massive tears in which adequate repair cannot be obtained arthroscopically)

For arthroscopic repair, the posterior portal is first created as the primary viewing portal for the arthroscope, followed by the anterior portal (working portal) for instruments.

For arthroscopic repair, the posterior portal is first created as the primary viewing portal for the arthroscope, followed by the anterior portal (working portal) for instruments.

Diagnostic arthroscopy should be performed before the initiation of any procedure, with careful evaluation of the glenohumeral joint, labrum, biceps tendon, rotator cuff, and joint capsule.

Diagnostic arthroscopy should be performed before the initiation of any procedure, with careful evaluation of the glenohumeral joint, labrum, biceps tendon, rotator cuff, and joint capsule.

For open repair, an incision is made in the anterior aspect of the shoulder lateral to the acromion along the Langer lines; access to the joint capsule is gained through the deltoid either by splitting the fibers (traditional open approach) or detaching it from the acromion (mini-open approach).

For open repair, an incision is made in the anterior aspect of the shoulder lateral to the acromion along the Langer lines; access to the joint capsule is gained through the deltoid either by splitting the fibers (traditional open approach) or detaching it from the acromion (mini-open approach).

Acromioplasty is typically performed as described earlier.

Acromioplasty is typically performed as described earlier.

The rotator cuff is evaluated to determine the degree of tear, the shape of the tear, and retraction.

The rotator cuff is evaluated to determine the degree of tear, the shape of the tear, and retraction.

Partial-thickness tears of less than 50% can be débrided with the shaver rather than repaired.

Partial-thickness tears of less than 50% can be débrided with the shaver rather than repaired.

Full-thickness tears and high-grade partial tears must be mobilized and repaired.

Full-thickness tears and high-grade partial tears must be mobilized and repaired.

Arthroscopic repair is performed by passing sutures through the cuff tissue and directly repairing it to the bone by suture anchors.

Arthroscopic repair is performed by passing sutures through the cuff tissue and directly repairing it to the bone by suture anchors.

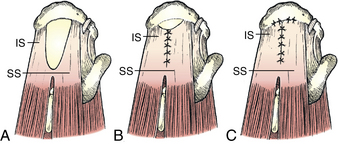

Margin convergence may be necessary before direct repair of tendon back to bone in the case of L-shaped or U-shaped tears (Fig. 2-15).

Margin convergence may be necessary before direct repair of tendon back to bone in the case of L-shaped or U-shaped tears (Fig. 2-15).

Sutures are then passed either in antegrade or retrograde fashion and are secured to suture anchors placed in the footprint (single row, double row, suture bridge technique, as preferred by the surgeon).

Sutures are then passed either in antegrade or retrograde fashion and are secured to suture anchors placed in the footprint (single row, double row, suture bridge technique, as preferred by the surgeon).

In open repair, direct suture repair to bone is performed by passing sutures through bone tunnels and then tying knots.

In open repair, direct suture repair to bone is performed by passing sutures through bone tunnels and then tying knots.

Sutures are tensioned, and the repair is examined before irrigation and closure of the portals and/or incision.

Sutures are tensioned, and the repair is examined before irrigation and closure of the portals and/or incision.

Estimated postoperative course

Initial postoperative visit (7 to 14 days)

Initial postoperative visit (7 to 14 days)

Shoulder instability

Shoulder instability may be traumatic or atraumatic.

Shoulder instability may be traumatic or atraumatic.

Traumatic shoulder dislocations most commonly occur with the shoulder in an abducted and externally rotated position causing immediate pain, shoulder deformity, and loss of motion.

Traumatic shoulder dislocations most commonly occur with the shoulder in an abducted and externally rotated position causing immediate pain, shoulder deformity, and loss of motion.

Patients may report a “dead” arm syndrome resulting from transient traction on the brachial plexus or the axillary nerve.

Patients may report a “dead” arm syndrome resulting from transient traction on the brachial plexus or the axillary nerve.

Atraumatic shoulder instability may be more vague, with pain or subluxation events during activity such as overhead throwing or swimming.

Atraumatic shoulder instability may be more vague, with pain or subluxation events during activity such as overhead throwing or swimming.

It is important to differentiate dislocation from subluxation during the history, as well as the number of episodes (acute, recurrent).

It is important to differentiate dislocation from subluxation during the history, as well as the number of episodes (acute, recurrent).

Other causes of shoulder dislocation include seizure disorders and electric shock (posterior dislocation).

Other causes of shoulder dislocation include seizure disorders and electric shock (posterior dislocation).

Hyperligamentous laxity can predispose to instability, as can a history of such conditions as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome or Marfan syndrome.

Hyperligamentous laxity can predispose to instability, as can a history of such conditions as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome or Marfan syndrome.

Physical examination

Acute dislocations produce deformity and loss of motion.

Acute dislocations produce deformity and loss of motion.

Decreased sensation occurs over the “deltoid patch” initially and resolves with time.

Decreased sensation occurs over the “deltoid patch” initially and resolves with time.

Apprehension and relocation tests are positive.

Apprehension and relocation tests are positive.

A positive sulcus sign with inferior instability, often bilateral, indicates multidirectional instability.

A positive sulcus sign with inferior instability, often bilateral, indicates multidirectional instability.

A positive supraspinatus stress test may indicate an associated rotator cuff tear in patients who are more than 40 years old.

A positive supraspinatus stress test may indicate an associated rotator cuff tear in patients who are more than 40 years old.

Shoulder and humerus