Hinge abduction occurs early in the fragmentation stage of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease and should be suspected when abduction and internal rotation are lost. It can be confirmed by an AP radiograph in abduction and internal rotation in which the ossific nucleus is not covered by the acetabulum. An arthrogram can then yield greater information regarding the reversibility of the hinge abduction. Hinge abduction should be considered a contraindication to containment by redirectional pelvic or femoral varus osteotomy. However, good results have been reported with acetabular augmentation via shelf procedures or Chiari osteotomies. Valgus femoral osteotomies have also been beneficial in the treatment of the Legg-Calvé-Perthes hip with hinge abduction.

Hinge abduction was first described by Catterall and by Grossbard in 1981. Since then, many authors have further elucidated the concept. It is now known that

Hinge abduction is present in 5% to 20% of hips with Legg-Perthes disease.

Hinge abduction can occur early in fragmentation phase, before the hip can be accurately classified by either the Herring lateral pillar or the Catterall methods.

The earliest clinical signs are loss of abduction and internal rotation of the hip.

As early hinge abduction occurs due to impingement on unossified cartilage, standard anteroposterior and frog lateral radiographs are unable to visualize it.

Hips with unrelieved hinge abduction have a very poor prognosis.

The best means of diagnosing hinge abduction is controversial. Most authors continue to use arthrography, as originally described, as the definitive radiographic test. Nakamura, citing the subjectivity of classical arthrographic diagnosis, devised an acetabular index, in which the medial cartilage space is divided by the acetabular width. Increase of this index with abduction is then taken as indicative of hinge abduction. This index corrects for magnification errors that might be present when using the image intensifier.

Reinker, seeking a diagnostic criterion available in the outpatient clinic, found that failure of the lateral pillar to pass under the acetabular edge with abduction of the internally rotated and extended hip was indicative of hinge abduction. This criterion is somewhat more stringent than the arthrographic criteria, as some hips that meet this test do not demonstrate hinge abduction on arthrography. The question is whether the general anesthesia used for the arthrogram masks hinge abduction that is present when the patient is awake. Should these patients then be treated as though they had hinge abduction or not? This question is unanswered at present. The author and colleagues have taken the view that these patients do have hinge abduction, but that it is reversible. They have treated them with abduction casts for 6 to 8 weeks. If the lateral pillar remains under the edge of the acetabulum, the author and colleagues treat them as they do patients without hinge abduction. If, however, patients are unable to maintain the hip in the reduced position, the author and colleagues treat them as though they have persistent hinge abduction.

Treatment

The treatment of patients with hinge abduction is controversial, but basically involves one of 4 types:

- 1.

Acetabular augmentation, either by Chiari osteotomy or by shelf arthroplasty; in either case, the goal is to remove the impingement on the acetabular edge by extending the effective edge of the acetabulum over the extruded portion of the femoral head

- 2.

Valgus femoral osteotomy, such that the impingement does not occur until the femur is widely abducted

- 3.

Reshaping of the femoral head or neck, with impinging structures being removed

- 4.

Capsulotomy to obtain reduction, followed by additional treatment as necessary.

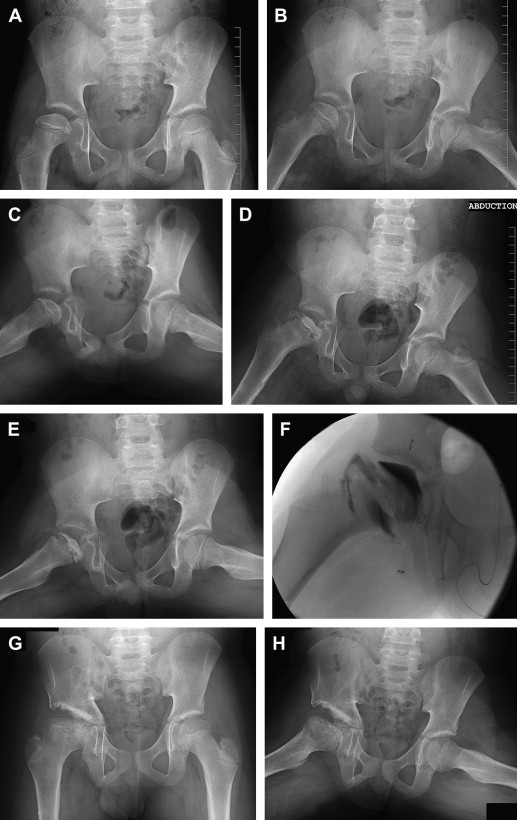

Chiari osteotomy is a well-established procedure in the treatment of Legg-Perthes disease, with good results being reported by many authors ( Fig. 1 ). Cahuzac performed 17 Chiari osteotomies in Legg-Perthes patients and reported 12 having regular femoral heads postoperatively, 4 irregular, and 1 very irregular. Fourteen patients were pain free at maturity. Bennett reported on 17 patients who had Chiari osteotomy with “painful, incongruent, subluxed hips.” At review, significant improvements of centre-edge angle and percent coverage were documented. No patients reported pain with normal activity. Using the Mitchell classification system, 12 were rated fair, and 1 poor. Reddy, in a series largely composed of patients with demonstrated hinge abduction, documented significant improvement of femoral head sphericity after Chiari osteotomy at mean age of 8.5 years. At maturity, 68% of patients were in Stulberg class 2, 18% Stulberg 3, and 14% Stulberg 4. Abduction and internal rotation improved in 72% of cases. Pain was relieved completely in 73% of patients, with 27% of patients having occasional painful episodes.

The value of shelf arthroplasty has also been well documented in the treatment of Legg-Perthes disease. Some have considered that shelf arthroplasty is contraindicated in the presence of hinge abduction. Kruse, however, reported good long-term results in patients with hinge abduction treated at a mean age of 8 years with preoperative traction, adducter tenotomy, and shelf arthroplasty. After mean 19 years of follow-up, 15 of the 20 hips were able to have Stulberg grading. Two hips were Stulberg class 2, seven class 3, five class 4 and one class 5. He was able to eliminate hinge abduction in 11 of 14 patients.

Freeman, in a study of shelf arthroplasty limited to patients having hinge abduction, documented excellent results, with 1 patient rated as Stulberg 1, 13 as Stulberg 2, 10 as Stulberg 3, two as Stulberg 4 and one as Stulberg 5. They documented a “striking” improvement of pain almost immediately postoperatively, with 24 of 28 patients being pain-free at final follow-up.

The rationale for capsulotomy is to decrease force at the acetabular edge by allowing greater abduction before the medial capsule becomes tight and creates a nutcracker effect on the femoral head. Capsular release has the potential, however, for allowing an increase in the degree of subluxation when the hip is adducted. The author and colleagues therefore view this as a possibly helpful adjunct to other techniques. Very little information is available about the results of capsular release.

Discussion

The best treatment for patients with hinge abduction continues to be controversial; however, much has been learned during the past decade, and good results have now been reported even with patients with severe deformity. Treatment of patients without hinge abduction is discussed in other articles. For the patient in whom hinge abduction is suspected, the author and colleagues obtain an abduction/internal rotation/extension radiograph. If this shows hinge abduction, the author and colleagues do arthrography. If the arthrogram shows reversible or absent hinge abduction, or if the extruded fragment can be covered adequately by a shelf, a shelf arthroplasty is performed. If a reasonable sized shelf would not adequately cover the femoral head, the author and colleagues perform Chiari osteotomy. The author and colleagues reserve valgus osteotomy for late patients with hinge abduction who are well into the regenerative phase of disease, as they feel that the literature shows better results from augmentation arthroplasty than for valgus osteotomy in patients treated early in the course. The author and colleagues continue to view cheilectomy as a last resort, to be used when range of motion is so poor that femoral osteotomy is unlikely to lead to an adequate result.

The author received no funding support for this article and has no financial disclosures relevant to this article.

Discussion

The best treatment for patients with hinge abduction continues to be controversial; however, much has been learned during the past decade, and good results have now been reported even with patients with severe deformity. Treatment of patients without hinge abduction is discussed in other articles. For the patient in whom hinge abduction is suspected, the author and colleagues obtain an abduction/internal rotation/extension radiograph. If this shows hinge abduction, the author and colleagues do arthrography. If the arthrogram shows reversible or absent hinge abduction, or if the extruded fragment can be covered adequately by a shelf, a shelf arthroplasty is performed. If a reasonable sized shelf would not adequately cover the femoral head, the author and colleagues perform Chiari osteotomy. The author and colleagues reserve valgus osteotomy for late patients with hinge abduction who are well into the regenerative phase of disease, as they feel that the literature shows better results from augmentation arthroplasty than for valgus osteotomy in patients treated early in the course. The author and colleagues continue to view cheilectomy as a last resort, to be used when range of motion is so poor that femoral osteotomy is unlikely to lead to an adequate result.

The author received no funding support for this article and has no financial disclosures relevant to this article.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree