Sepsis and Total Knee Arthroplasty

Sepsis occurring after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a disastrous complication. I have been most fortunate in my career that so far, after more than 5000 primary TKAs, none of my patients have experienced an early deep infection. I have seen late “metastatic” infection to primary TKAs at a rate that is 0.6% at average 10-year follow-up.1 What follows has been gleaned from my experience treating my own patients with late infection, as well as other patients with septic knees who have been referred to me.

Perioperative Prophylactic Measures

It is obviously preferable to prevent an infection rather than have to treat one. Prophylactic measures can be taken before, during, and after surgery to minimize the chance for infection.

All patients should be screened preoperatively for potential sites of active infection that could spread to the knee. The most common are oropharyngeal and urologic. Any patient with a chronic infection such as sinusitis or pharyngitis should be cleared by an otolaryngologist before surgery. Similarly, patients with chronic dental infection in need of reconstructive procedures should have these performed before the arthroplasty.

It is not unusual to encounter a female patient with a history of recurrent urinary tract infection. A urinalysis and urine culture should be obtained preoperatively on all patients.

Any active urinary tract infection should be treated, and chronic problems should be cleared by a urologist. If a preoperative urine culture is positive but few white cells are present in the sediment and the patient is totally asymptomatic, the surgery need not be canceled. A repeat clean-catch or catheterized specimen can be helpful to clarify whether antibiotic treatment of the infection is necessary. In the presence of a positive culture of greater than 100,000 colonies and benign sediment in an asymptomatic patient, I often start oral antibiotics preoperatively and obtain the catheterized specimen in the operating room before the arthroplasty.

Preoperative Germicidal Skin Scrub

All my patients are instructed to use a chlorhexidine germicidal skin scrub (e.g., Hibiclens) twice daily for 2 days before their surgery. In theory, this should decrease the colonization of bacteria on the patient’s skin and the chance for contamination.

Surgical Preparation and Draping

It has been my practice to prepare the entire extremity, including the foot, for TKA. The foot is draped out of the surgical field, of course, but I am more comfortable with this area being surgically prepared in the event of any breakdown in the drapes that cover the foot. I use a surgical stockinette over the prepared foot up to the level of the tourniquet. The stockinette has a double layer. The outer layer is cut, and the incision is defined with a marking pen. The inner stockinette is then cut and reflected medially and laterally for a few centimeters. The skin incision is drawn out, and then the entire field is sealed with a povidone-iodine–impregnated adhesive drape. Care is taken to not actually touch the skin during this draping procedure, and fresh outer gloves are applied after it is completed (see Chapter 3).

Laminar Air Flow Versus Ultraviolet Lights

I am often asked by ex-fellows or residents whether laminar airflow or ultraviolet (UV) light is better. Each method has advantages and has been shown to be an effective deterrent to infection. The UV light method is less expensive and requires all operating room personnel to cover up to shield their eyes and skin, which may decrease the potential for the shedding of bacteria by personnel. The fact that UV lights are potentially “sterilizing” the field during the procedure is reassuring when I am performing sequential bilateral TKAs. When I am using laminar airflow for bilateral arthroplasty, I sequester the instruments that are used on the first knee during the skin closure and pass them off the operating field after they have been used. A change of outer gloves is also performed between the procedures (see Chapter 12).

Intravenous Antibiotics

Intravenous antibiotics have long been shown to decrease the incidence of perioperative orthopedic wound infection. I commonly use a second-generation cephalosporin, giving 1 g intravenously at least 10 minutes before inflation of the tourniquet. A second 1 g is administered at the time the tourniquet is deflated to maximize the concentration of antibiotic in the evolving wound hematoma. The antibiotics are continued every 8 hours for three additional doses. In patients allergic to penicillin, I still administer the cephalosporin, unless the allergy has been one of anaphylaxis. A test dose is given with caution and under surveillance by the anesthesiologist. If the test dose is well tolerated, the standard protocol is used. Although there is said to be a crossover in sensitivity between penicillin and cephalosporins of as much as 15% in terms of allergy, in hundreds of cases over the past 20 years using this protocol, I have not yet seen this crossover. This test dose therefore allows a penicillin-sensitive patient to receive a cephalosporin in the future, should that be appropriate.

Proper Skin Incision

Prior skin incisions around the knee must be respected. The knee does not tolerate multiple parallel incisions, especially a medial incision made parallel to an old lateral incision (see Chapter 14). If skin breakdown were to occur, infection would be likely. My standard incision is approximately 15 cm long. It begins 5 cm above the patella centered over the shaft of the femur, crosses the medial third of the patella, and ends distally at the medial aspect of the tibial tubercle. In general, when prior incisions are present, it is best to use the most lateral incision that allows arthroplasty or the most recent incision that healed without difficulty (see Chapter 14). Medially based flaps are safer than laterally based flaps. In questionable cases, the skin incision can be made with the tourniquet deflated. If the wound edges appear poorly vascularized, the surgery can be aborted and plastic surgical consultation obtained. I have used tissue expanders successfully on several occasions in the presence of extremely thin or adherent skin after trauma, a skin graft, or an old healed sinus tract.

Wound Care

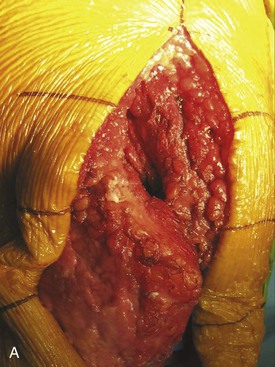

After the skin incision and arthrotomy, I always sew in wound towels along the capsule that protect the subcutaneous tissue from debris and from drying out under the operating room lights. The towels are irrigated with saline solution. When they are removed at the end of the procedure, it is always impressive to see how healthy the tissues appear compared with the brown, dried-out appearance of the subcutaneous tissues when wound towels have not been used (Figure 13-1).

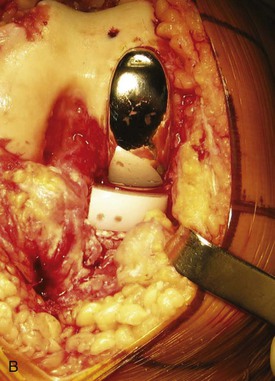

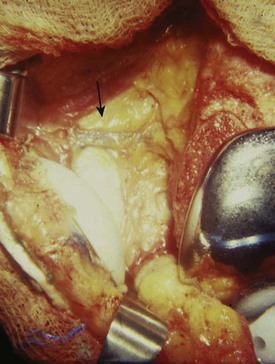

Infection is often a result of wound necrosis secondary to compromise of blood supply to the skin and subcutaneous tissue. For this reason, in a lateral retinacular release, it is beneficial, if possible, to preserve the lateral superior genicular artery (Figure 13-2). Infection also can be the result of breakdown of the wound caused by a large hematoma. To minimize this possibility, I deflate the tourniquet before wound closure, to check for significant bleeding points.

During rehabilitation, if the capsular closure loses its integrity, a wound problem can occur. For this reason, I prefer an interrupted capsular closure with a strong monofilament suture. My preference is no. 1 polydioxanone (PDS).

The use of suction drains after TKA is controversial. The studies that support the contention that they are unnecessary involve only several hundred cases. In my opinion, a review of a thousand consecutive cases without the use of a drain would reveal at least one significant complication such as wound breakdown, necrosis, secondary infection, or even compartment syndrome that cost the patient and society more than the price of a thousand standard suction drains. These drains do their most important work during the first several hours after surgery. I always discontinue their use on the morning after surgery. If for some reason the output is excessive, I flex the knee for 30 minutes and clamp the drains. If excessive output continues, I consider removing the drains. The wound is then observed carefully over the next 24 hours, and, if necessary, the patient can be brought back to the operating room to control any bleeding. In my experience, this is rarely necessary.

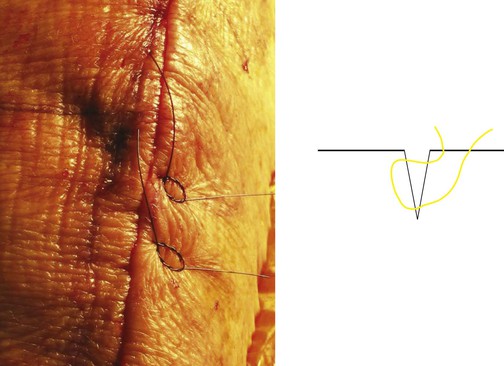

The skin closure is one of the most important parts of TKA. It must be meticulously performed with the skin edges accurately opposed. I prefer the modified Donati suture (Figure 13-3). This is a vertical mattress suture that is subcuticular on the lateral side (the side more prone to skin necrosis). Interrupted closure is preferred over a running subcuticular stitch because the length of a knee incision increases as much as 40% from extension to flexion. This movement puts a repetitive strain on the subcuticular suture. An interrupted closure allows the removal of a few localized stitches to deal with a superficial wound separation or infection.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree