Procedure Selection for the Flexible Adult Acquired Flatfoot Deformity

Matthew J. Hentges, DPMa, Kyle R. Moore, DPMa, Alan R. Catanzariti, DPMa∗acatanzariti@faiwp.com and Richard Derner, DPMb, aDivision of Foot and Ankle Surgery, West Penn Hospital, Allegheny Health Network, 4800 Friendship Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15224, USA; bPrivate Practice, Associated Foot and Ankle Centers of Northern Virginia, 1721 Financial Loop, Lake Ridge, VA 22192, USA

Adult acquired flatfoot represents a spectrum of deformities affecting the foot and the ankle. The flexible, or nonfixed, deformity must be treated appropriately to decrease the morbidity that accompanies the fixed flatfoot deformity or when deformity occurs in the ankle joint. A comprehensive approach must be taken, including addressing equinus deformity, hindfoot valgus, forefoot supinatus, and medial column instability. A combination of osteotomies, limited arthrodesis, and medial column stabilization procedures are required to completely address the deformity.

Introduction

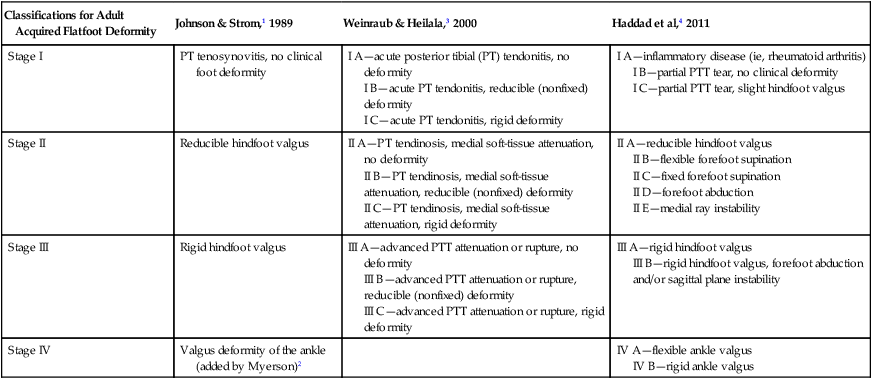

In their classic article, Johnson and Strom1 described 3 stages of PTTD beginning with painful synovitis progressing to a nonfixed flatfoot deformity and ending with a fixed arthritic flatfoot. This classification system was later modified by Myerson2 to include a fourth stage encompassing deformity of the ankle. Weinraub and Heilala3 created a classification system and an algorithmic surgical approach for the treatment of AAFF. This classification system combined both osseous and soft-tissue components into a staging (soft-tissue component) and grading (osseous component) system. Selection of surgical procedures was based off of this combined staging and grading system. A recent classification published by Haddad and colleagues4 divides stage II into 5 different subcategories (A–E) (Table 1). This article focuses on the pathoanatomy, diagnosis, and current surgical management of the nonfixed AAFF based on these contemporary classifications.

Table 1

Comparison of classification systems for adult acquired flatfoot

| Classifications for Adult Acquired Flatfoot Deformity | Johnson & Strom,1 1989 | Weinraub & Heilala,3 2000 | Haddad et al,4 2011 |

| Stage I | PT tenosynovitis, no clinical foot deformity | I A—acute posterior tibial (PT) tendonitis, no deformity I B—acute PT tendonitis, reducible (nonfixed) deformity I C—acute PT tendonitis, rigid deformity | I A—inflammatory disease (ie, rheumatoid arthritis) I B—partial PTT tear, no clinical deformity I C—partial PTT tear, slight hindfoot valgus |

| Stage II | Reducible hindfoot valgus | II A—PT tendinosis, medial soft-tissue attenuation, no deformity II B—PT tendinosis, medial soft-tissue attenuation, reducible (nonfixed) deformity II C—PT tendinosis, medial soft-tissue attenuation, rigid deformity | II A—reducible hindfoot valgus II B—flexible forefoot supination II C—fixed forefoot supination II D—forefoot abduction II E—medial ray instability |

| Stage III | Rigid hindfoot valgus | III A—advanced PTT attenuation or rupture, no deformity III B—advanced PTT attenuation or rupture, reducible (nonfixed) deformity III C—advanced PTT attenuation or rupture, rigid deformity | III A—rigid hindfoot valgus III B—rigid hindfoot valgus, forefoot abduction and/or sagittal plane instability |

| Stage IV | Valgus deformity of the ankle (added by Myerson)2 | IV A—flexible ankle valgus IV B—rigid ankle valgus |

Pathoanatomy

The pertinent anatomy of the nonfixed AAFF includes not only the PTT but also the spring ligament, deltoid ligament, the articulations of the tritarsal complex (talonavicular joint, subtalar joint, and calcaneal-cuboid joint), and the medial column (naviculocuneiform joint and first tarsometatarsal joint). The PTT takes its origin from the posterior aspect of the tibia, fibula, and interosseous membrane. The tendon courses posterior to the medial malleolus and inserts into the navicular tuberosity and multiple additional insertions across the plantar aspect of the midfoot.5 The vascular supply to the PTT consists of branches of the posterior tibial artery. Proximally, muscular branches feed the tendon. Distally, periosteal branches feed the tendon. A watershed area, or zone of hypovascularity, has been identified in the retromalleolar region of the PTT, which often corresponds to one of the sites of degenerative changes within the tendon.6 The degenerative changes within the tendon may be the result of repetitive microtrauma or compromised repair response due to the limited vascular supply.7

The spring ligament complex extends from the anterior margin of the sustentaculum tali to the plantar medial aspect of the navicular and cradles the plantar medial aspect of the talar head.7 This ligamentous complex comprises a superomedial and inferior calcaneonavicular ligament. The superomedial calcaneonavicular ligament is commonly involved in the AAFF deformity and is often found intraoperatively to be attenuated or torn.8

The deltoid ligament complex has multiple components, both superficial and deep. It blends distally with the spring ligament complex and the talonavicular joint capsule.7 Attenuation of the deltoid ligament due to long-standing valgus deformity of the hindfoot can lead to valgus tilting of the talus within the ankle mortise, which is the case in stage IV AAFF.

Muscle balance of the lower extremity is altered with dysfunction of the PTT and resultant AAFF. The PTT produces inversion of the hindfoot and locks the midtarsal joint to maintain the medial longitudinal arch and create a rigid lever for push off during normal gait. When the PTT is diseased, it no longer creates an inversion moment on the hindfoot and the peroneus brevis gains a mechanical advantage. The midtarsal joint is then unlocked, and the hindfoot can no longer function as a rigid lever for push off. Moreover, during heel strike, the eccentric contraction of the PTT is limited, thereby increasing the valgus moment of the hindfoot. In combination with an equinus contracture, there is increased stress placed on the medial column of the foot. The repetitive biomechanical alteration in the gait cycle creates progressive midfoot collapse, forefoot abduction, and hindfoot valgus.9 There are 2 potential mechanical causes of AAFF. First, medial column instability resulting in a forefoot supinatus deformity and a compensatory hindfoot valgus.7 Second, contracture of the posterior muscle group, either gastrocnemius equinus or gastrocnemius-soleus equinus, results in breakdown of the medial column of the foot, peritalar subluxation, and subfibular impingement due to hindfoot valgus.6

Diagnosis of stage II AAFF

Clinical Presentation

Many patients present for evaluation and treatment during their fifth or sixth decade of life. Often, they have had a flatfoot their entire life, and relate a gradual onset of pain over months to years. For those without a congenital flatfoot, they may be able to correlate the decrease in arch height and onset of symptoms. Most patients deny an acute traumatic event; however, some may identify a specific event that preceded the pain and loss of arch height (Fig. 1). Standing for extended periods and normal ambulation typically triggers pain in the medial hindfoot and posteromedial ankle. Patients often note dysfunctional gait, with a decreased ability to run and a loss of push off strength.7 It is important to obtain a detailed history, including trauma to the foot and/or ankle, family history of flatfeet, chronic steroid use, diabetes mellitus, inflammatory arthritides, and smoking. It is also important to identify patients with multiarticular hypermobility, such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, as these patients often present similar to PTT dysfunction. Previous attempts at treatment should also be elicited, including both nonoperative and operative interventions.

Clinical Examination

The comprehensive assessment of the patient with symptomatic flatfoot should be firmly rooted in a thorough history and physical examination. Careful attention to complaints such as arch fatigue, ankle discomfort, or proximal lower extremity pain should be noted. It is important to formulate a methodical and systematic approach to examine the patient in a complete yet timely manner. The stepwise progression of PTTD and AAFF has been well documented during the past 2 decades.1–3,10–12 The distinct clinical features originally proposed by Johnson and Strom1 have allowed the practitioner to better understand the continuum of PTTD and AAFF.

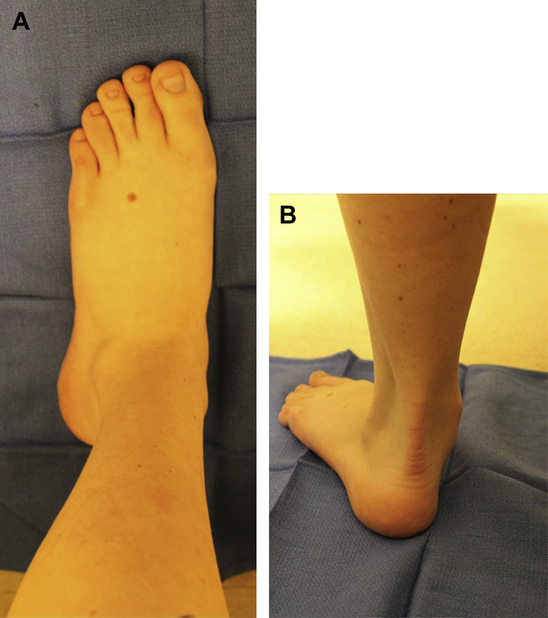

The affected lower extremity should be carefully compared with the contralateral limb with the patient seated in the examination chair. A fullness or swelling of the medial arch and ankle can obscure the normal anatomic contours of the tibial malleolus. Subtle erythema or mild callus formation may appear secondary to a partially subluxed talar head or increased medial arch pressure.6 Palpation of the PTT often elicits tenderness along its course, as well as at the navicular insertion site. Manual strength of the PTT can be easily tested and also should be carefully compared with the unaffected side. Proper positioning of the foot to diminish the contribution of the tibialis anterior tendon is important to fully isolate the strength and function of the PTT.13 The affected side may appear slightly weak, and/or pain can be provoked if the tendon is palpated while the PTT is being actively contracted. These subtle clues may serve as the few revealing factors to an early-stage deformity as the painful foot may appear structurally similar to the unaffected side when non–weight bearing (Fig. 2).

The importance of the medial hindfoot supporting structures, namely, the spring ligament and deltoid ligament, and their role in the valgus hindfoot deformity has been emphasized.7,14,15 Although it may be difficult to directly isolate these structures during the physical examination, their importance cannot be marginalized during the assessment. Furthermore, concomitant deformities such as hallux valgus can frequently be seen in AAFF and may serve as additional sources of discomfort in the patient with AAFF.16,17

Non–weight-bearing joint motion, including that of tibiotalar, subtalar, and midtarsal joints, should also be thoroughly assessed. The definition of a nonfixed flatfoot can be characterized by a reducible hindfoot. This condition is noted on clinical examination through manual manipulation. DiGiovanni and colleagues,18,19 as well as numerous other investigators, have reported the increased mechanical loads that equinus contracture can produce on the foot and ankle.20 Thus, ankle joint dorsiflexion necessitates appropriate evaluation and should not be overlooked. A properly performed Silfverskiold examination is crucial not only in revealing the presence of equinus deformity but also in determining the driving component behind reduced ankle joint dorsiflexion (gastrocnemius vs gastrocnemius-soleus vs osseous) and surgical treatment plan.21

When viewing the posterior aspect of the affected lower extremity, the forefoot often appears abducted in relation to the rearfoot. This condition predisposes the patient to the often quoted “too many toes” sign when compared with the contralateral side.1 A mild to moderate increase in valgus hindfoot position is often present, which should reduce on rising up on the balls of both feet simultaneously. While instructing the patient to lightly stabilize himself or herself on a flat wall or table, the practitioner should attempt to perform the “single heel rise test,” as this maneuver is often positive in patients with PTT. When inflammation and/or attenuation of the tendon is present, rising onto the forefoot may be painful or even impossible to perform.1–3,6,7,10–13,15,22 A dysfunctional PTT is unable to provide an effective supinatory moment to stabilize the midtarsal joint, and the observer can appreciate instability in the arch as the patient attempts to rise up on the toes on the affected foot. Even if the patient is able to perform this maneuver on the initial effort, multiple repeated attempts at heel rise often worsen medial ankle and/or arch discomfort.2,12

Hintermann and Gachter23 described the “first metatarsal rise test” as another sensitive examination to appraise the function of the PTT. This evaluation entails having the patient stand with equally distributed weight on both feet and the examiner passively moving the affected hindfoot into a varus position. In the case of a dysfunctional PTT, the first metatarsal head rises from the weight-bearing surface. Conversely, if the tibialis posterior tendon is functioning normally, the patient is able to keep the first metatarsal in contact with the floor.

The true extent of their pain and discomfort can typically be appreciated as the patient with symptomatic AAFF is asked to walk barefoot across the floor. The gait analysis may expose an antalgic limp that can be coupled with more proximal postural symptoms. The patient may seem to remain in stance phase longer on the affected foot as heel rise occurs later in the gait cycle. Dynamic side-by-side comparison of both feet may reveal a noticeable loss of arch height and increased abduction when compared with the unaffected side. When underlying equinus deformity exists, the examiner may note additional proximal compensatory mechanisms such as genu recurvatum, lumbar lordosis, and forward postural position.22

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree