Scope Synovectomy

Bryan Haughom

Brandon J. Erickson

Charles Bush-Joseph

DEFINITION

Synovial tissue is found lining the joint capsules and tendon sheaths of the body.

Synovitis is characterized by inflammation of the synovial membrane and can be found in a number of pathologic conditions as well as a normal response to injury.

Clinically, synovitis results in painful, swollen, stiff joints. Continued joint inflammation may result in articular cartilage damage and osteopenia.

After medical management has been exhausted, surgery is often indicated if the patient experiences continued pain, swelling, and mechanical symptoms.

A number of conditions are associated with synovitis of the knee, including inflammatory arthritides (rheumatoid arthritis, lupus erythematosus, psoriatic arthritis), degenerative processes (osteoarthritis), proliferative disorders (pigmented villonodular synovitis [PVNS], synovial chondromatosis), crystalline arthropathies (gout, pseudogout), conditions which result in hemarthrosis (trauma, hemophilia A and B, von Willebrand disease, chronic anticoagulation therapy), lead synovitis, hemangiomas, intra-articular adhesions, fat pad fibrosis, hemophilic synovitis, and fibrotic ligamentum mucosum to name a few.4,5,6,9,10,14,20,21

ANATOMY

Synovial tissue is the specialized mesenchymal lining of joints. It is composed of a thin layer of synoviocytes above a fibrovascular zone (vascular tissue, fat, connective tissue).

Grossly, it appears as smooth and transparent; however, in the setting of inflammation, it becomes thickened, red, and markedly more villous.

The primary function of synovial tissue is to provide fluid for joint lubrication and nutrient oxygen and proteins.

Histologic hallmarks of chronic synovitis include hyperplasia of the intimal lining, lymphocyte infiltration, and blood vessel proliferation. In the setting of recurrent hemarthroses, variable amounts of hemosiderin may be evident on microscopic examination.

Patients with chronic synovitis can have localized or diffuse disease depending on their underlying condition. When localized, imaging studies such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can help direct arthroscopy. With diffuse disease, it is vital to visualize all aspects of the knee during surgical synovectomy to ensure complete eradication of the offending tissue.

PATHOGENESIS

The pathogenesis of synovitis is variable depending on the underlying etiology (eg, inflammatory arthritis vs. recurrent hemarthrosis vs. proliferative disorders such as PVNS).

In chronic synovitis, the synovial lining undergoes hyperplasia, angiogenesis, and increased cellularity (inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and macrophages).

Rheumatoid arthritis is an example of an inflammatory arthritis, which causes chronic synovitis. It presents with the insidious onset of morning stiffness and polyarthralgias. The synovitis that ensues is thought to be an acute autoantibodymediated inflammatory process.

PVNS is a proliferative disorder characterized by nodules and villi in the synovium of joints and tendon sheaths. Typically, PVNS is a monoarticular disease with a predilection for the knee.

Hemophilia is an X-linked deficiency of clotting factors (hemophilia A, factor VIII; hemophilia B, factor IX), leading to bleeding of varying severity. This condition often results in recurrent hemarthrosis, particularly in the knee, which leads to chronic progressive synovial hyperplasia, pain, and joint destruction.

NATURAL HISTORY

Repeated bouts of acute synovitis or chronically inflamed synovium can lead to chronic pain, limited range of motion, and ultimately joint degeneration and arthrosis.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A full personal and family history of rheumatologic and hematologic disorders should be elicited, including involvement of other joints and previous episodes of joint pain and swelling.

The patient may have a history of recurrent swelling, pain, warmth, stiffness, and mechanical symptoms (FIG 1).

Patients should be evaluated for the stigmata of psoriasis (silver plaques), lupus (malar rash), and rheumatoid arthritis (rheumatoid nodules).

PVNS can cause mechanical symptoms such as locking, similar to a meniscal tear. A palpable mass may be present.

Intermittent symptoms are more common with localized PVNS; diffuse PVNS often presents with a more chronic course.

During the physical examination, the surgeon should look for effusion, tenderness, warmth, mass, and synovial thickening.

Range of motion: Loss of flexion or extension may indicate arthrofibrosis.

Lachman test: assesses competence of anterior cruciate ligament

Posterior drawer test: assesses competence of posterior cruciate ligament

Varus stress test: assesses competence of lateral collateral ligament

Valgus stress test: assesses competence of medial collateral ligament

Dial test: assesses competence of posterolateral corner and posterior cruciate ligament

Malalignment and ligamentous insufficiencies are noted and will likely preclude arthroscopic synovectomy, given their association with joint destruction.

Joint aspiration can be therapeutic and diagnostic.

Synovial fluid analysis should include documentation of fluid color (ie, brownish in PVNS, indicating recurrent bleeding), testing for rheumatoid factor, complement levels, cell count, Gram stain, culture, and crystal analysis

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Radiographs are important to document the extent of joint destruction and may point toward the etiology of the synovitis.

The surgeon should look for the characteristic rheumatologic signs of periarticular erosions and osteopenia.

Radiologic signs of PVNS and gout include cystic, sclerotic, or erosive changes.

Linear calcifications within articular cartilage and menisci are found in pseudogout.

Synovial chondromatosis is often visible on plain films.

Advanced degenerative disease is associated with a poorer prognosis after arthroscopy.17

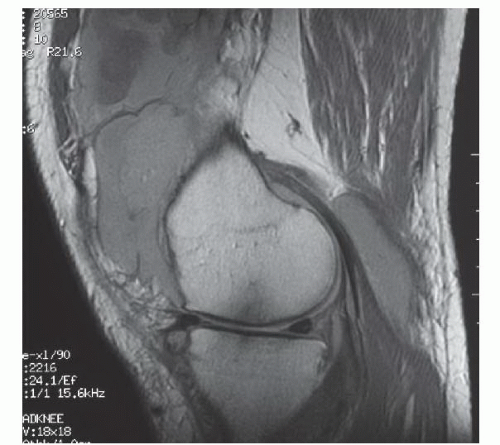

MRI is helpful to assess the scope of joint involvement before surgery (FIG 2).

Nodular PVNS can be readily seen as low signal on both T1 and T2 images.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Synovial disorders

Infection

Degenerative joint arthrosis

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Once the etiology of the synovitis is determined, first-line conservative treatment includes medical management of the underlying disease.

Oral anti-inflammatory medications may be used as well as intra-articular corticosteroid injections.

Gentle physical therapy can aid in maintenance of range of motion.

If the underlying cause is determined to be infection, there is often no trial of nonoperative management.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Both arthroscopic and open synovectomies have been described; however, arthroscopic synovectomy allows the identification and management of synovial lesions that may be missed with open procedures. Additionally, arthroscopic synovectomy allows for reevaluation after the index procedure with relatively low morbidity.11,18

Arthroscopic synovectomy can be the definitive treatment for the many of the aforementioned synovial disorders.

For more chronic or recurring conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis or hemophilic synovitis, this surgery can reduce the severity of pain and dysfunction commonly associated with these pathologies. It can reduce the number of recurrences and may slow the progression of joint arthrosis.11

Preoperative Planning

Preoperative flexion and extension cervical spine radiographs are necessary to rule out instability in rheumatoid patients.

Appropriate medical clearance is necessary to keep perioperative complications to a minimum.

General anesthesia rather than local anesthesia is recommended because the procedure can be lengthy. An epidural may also be used when medically indicated and may aid in postoperative pain relief. A Foley catheter may be used in anticipation of prolonged anesthesia, although this is rarely indicated.

Equipment

4.5-mm 30-degree arthroscope

4.5-mm 70-degree arthroscope (available if visualization is not adequate with 30-degree scope)

Small suction shaver

Arthroscopic electrocautery

Arthroscopic basket

Examination under anesthesia should be performed prior to the procedure. Care should be taken to document the presence of effusion, range of motion, ligamentous stability, and patellar mobility and tracking. Using a goniometer for exact measurements is helpful for following the postoperative rehabilitation process. Examination of the contralateral knee should always be performed for comparison.

Positioning

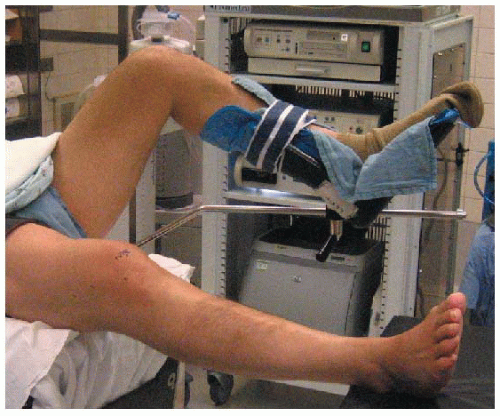

The patient is placed supine and brought to the edge of the bed to ensure that the leg may be easily hung over the side (the medial malleoli should be at the edge of the bed).

An arthroscopic leg holder should not be used as it may prohibit the use of the superomedial and superolateral portals.

Alternatively, an arthroscopic lateral post may be placed midthigh on the side of the operative bed.

A well-padded thigh tourniquet is placed high on the operative leg.

The contralateral leg is placed in a well-padded leg holder, flexing the hip and knee, with the hip in slight abduction. Compressive wrapping or sequential compression stockings should be used on the contralateral leg owing to the length of the procedure (FIG 3).

The foot of the bed is dropped, allowing the operative leg to hang free. The bed should be reflexed to produce slight hip flexion, decreasing the chance of femoral nerve palsy that may be associated with excessive hip extension and leg traction.

A suction canister trap should be set up for biopsy collection.

A grounding pad should be placed for use of an electrocautery device.