Scope for Femoroacetabular Impingement

Christopher M. Larson

Patrick M. Birmingham

DEFINITION

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is the result of abnormal contact between the proximal femur and the acetabular rim.

Abnormalities can be identified on either the femoral or acetabular side but are more commonly seen on both sides.

ANATOMY

The proximal femur and acetabulum normally articulate without abutment through a physiologic range of motion (ROM).

Required ROM, however, is variable depending on the activities performed, with less range required for sedentary individuals and extreme range required for activities such as dance, ballet, and hockey goalies.

The acetabulum normally is anteverted 12 to 16.5 degrees.

The acetabulum normally covers the femoral head to a depth that avoids impingement (ie, overcoverage) and instability (ie, dysplasia or undercoverage) with a horizontal, thin sourcil (ie, the weight-bearing zone).

The proximal femur normally has a spherical head-neck contour and appropriate offset that allows for impingementfree ROM.

The normal femoral neck-shaft angle is 120 to 135 degrees; the femoral neck typically is anteverted 12 to 15 degrees.

The acetabular labrum functions to create a fluid pressurization seal with the femoral head.8

It is important to recognize and respect the location of the retinacular vessels that have been shown to enter the antero-and posterolateral portions of the femoral neck and supply the majority of the femoral head’s blood supply.

The capsule is an important hip stabilizer and should be preserved and repaired to maintain soft tissue stability, particularly in dysplastic variants, generalized hypermobility, and connective tissue disorders.3

PATHOGENESIS

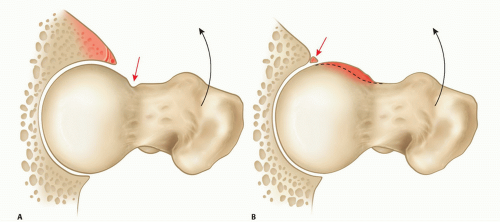

Pincer impingement is the result of contact between an abnormal acetabular rim and femoral head-neck junction (FIG 1A).

Pincer impingement typically is the result of a globally deep acetabulum (coxa profunda), focal anterior overcoverage (acetabular retroversion), or, less commonly, posterior overcoverage.

It leads to labral bruising and degenerative tearing and eventually may result in ossification of the labrum and contrecoup posterior acetabular chondral injury.

Global overcoverage is more frequent in females, whereas acetabular retroversion is more common in males.

Cam impingement is the result of contact between an abnormal femoral head-neck junction and the acetabulum (FIG 1B).

The abnormal femoral head-neck junction is typically secondary to an aspherical anterolateral head-neck junction but also can be secondary to a slipped capital femoral epiphysis, femoral retroversion, coxa vara, malreduced femoral neck fracture, and, less commonly, posterior femoral head-neck abnormalities.

Cam impingement results in a shearing stress to the anterosuperior acetabulum, with predictable chondral delamination and labral detachment or tearing in some cases.

Although cam impingement is reported to predominate in young athletic males and pincer impingement in middleaged women, most patients with FAI have a combination of both cam and pincer impingement.

Extra-articular sources of impingement have been recently described.

Anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS) impingement is an increasingly recognized type of acetabular-based impingement.

The AIIS serves as the origin of the direct head of the rectus femoris, and impingement can be secondary to prior avulsion injury, pelvic osteotomy, or developmental as seen in the setting of acetabular retroversion.12,18,26

Ischiofemoral impingement is a rare type of proximal femoral-based impingement that occurs between the lesser trochanter and the ischial tuberosity.

The quadratus femoris occupies this space and may be compressed when this space is reduced.

The normal distance between the lesser trochanter and the ischial tuberosity is reported to be 20 mm. This space is reported to be reduced to around 13 mm in patients with ischiofemoral impingement.

In addition, women, as a result of the wider positioning of their ischial tuberosities, appear to be at greater risk.30

NATURAL HISTORY

The likelihood of an individual with untreated FAI developing hip osteoarthritis is unknown because there have been no longitudinal studies prospectively following these patients before the development of symptoms.

Clinical experience with over 600 surgical dislocations of the hip in patients with FAI has revealed a strong association of this disorder with progressive acetabular chondral degeneration, labral tears, and progressive osteoarthritis.1,7,9

It is now well accepted that many patients with FAI will develop progressive chondral and labral injury, which can ultimately lead to end-stage hip osteoarthritis.

One population study suggests that there is a 15% to 19% prevalence of deep acetabular socket and 5% to 19% prevalence of pistol grip deformity. This population had a relative risk ratio of developing hip osteoarthritis of 2.2 to 2.4.11

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients typically are young to middle aged (second through fourth decade) at presentation with complaints of groin pain exacerbated by physical activity.

Prolonged sitting, arising from a chair, putting on shoes and socks, getting in and out of a car, and sitting with their legs crossed often exacerbate the symptoms.

We have found that patients may have a history of siblings, parents, and grandparents with hip pain or osteoarthritis of the hip, and patients may have milder or similar symptoms in the contralateral hip.

Patients often have had pain for months to years with the diagnosis of chronic low back pathology, hip flexor strains, and sports hernias/athletic pubalgia and not infrequently have had other surgeries without relief of their pain.28

Physical examinations should include the following:

Evaluation of hip ROM: Global ROM restriction indicates advanced osteoarthritis.

Anterior impingement test: Groin pain indicates anterolateral rim pathology.

Posterior impingement test: Groin pain or posterolateral pain indicates posterolateral rim pathology.

Extension/abduction and flexion/abduction indicates lateralbased pathology.

FABER test: FABER means flexion, abduction, and external rotation of the hip. Increased distance from the lateral knee to the examination table can indicate femoroacetabular impingement.

For subspine impingement, there is pain with straight flexion, restricted flexion, and, often, tenderness to palpation of the AIIS that recreates the flexion-based discomfort.

For ischiofemoral impingement, the symptoms can be reproduced by a combination of extension, adduction, and external rotation (ER).

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographs including an anteroposterior (AP) pelvis, a frog-leg lateral, 45-degree modified Dunn lateral or a crosstable lateral, and false-profile view are obtained.

The AP radiograph should have a coccyx to symphyseal distance of 0 to 2 cm, with the coccyx centered over the symphysis to properly evaluate acetabular version.

The following are measured on the AP radiograph (FIG 2A):

A lateral center edge angle of 25 to 40 degrees distinguishes deep acetabulum from dysplasia.

The presence of a crossover sign represents retroversion and can indicate either local anterior overcoverage or superior posterior undercoverage.

The posterior wall sign indicates posterior undercoverage (retroversion).

Extension of the AIIS below the sourcil and cortical sclerotic change may be indicative of AIIS impingement.

Decreased femoral head-neck offset and asphericity can be indicative of cam-type morphology.

A decreased femoral neck-shaft angle indicates coxa vara and may contribute to impingement.

The frog-leg lateral, 45-degree modified Dunn lateral, and or cross-table lateral views with 15 degrees internal rotation (IR) should be evaluated for the following:

Alpha angle: normally less than 50 to 55 degrees (anterolateral prominence/aspherical femoral head-neck junction; FIG 2B).25

Femoral head-neck offset and offset ratio: Normal femoral head-neck offset is greater than 8 to 11 mm and the normal femoral head-neck offset ratio is greater than 0.15.

Femoral head-neck cystic changes and sclerosis

The false profile is used to evaluate the following:

Anterior center edge angle: anterior over- and undercoverage

Excessive anterior and distal extension of the AIIS: Normally, the distal extent of the AIIS is proximal to the acetabular rim.

Anterior and posterior joint space

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) arthrogram is useful to evaluate for the following:

Labral and chondral pathology, acetabular version, and deformity of the femoral head-neck junction, which is best seen on the axial cuts and, in particular, with radial imaging (FIG 2C).

Femoral neck version: Retroversion/torsion may contribute to impingement, whereas excessive anteversion/torsion can contribute to instability; measurements require additional cuts through the distal femoral condyles.

Synovial herniation pits/impingement cysts at the femoral head-neck junction are also indicative of FAI.

An anesthetic agent can be included with the gadolinium to verify the hip joint as the source of pain, which is indicated by temporary pain relief with provocative maneuvers in the first couple of hours after the injection. Occasionally, the high volume of such an injection can lead to capsular distention with increased pain. Alternatively, a lower volume (<5 mL) of anesthetic-only injections can be used for diagnostic purposes.

The normal distance between the lesser trochanter and the ischial tuberosity is said to be 20 mm. This space is said to be reduced to around 13 mm in patients with ischiofemoral impingement.13

Three-dimensional computed tomography (CT) scanning can be invaluable and obtained in all or select cases:

The area of impingement can be more accurately mapped.

This may be done routinely in cases of subtle FAI or suspected unusual locations of FAI (eg, posterior femoral head/neck prominences) or for revision cases in order to better assess prior bone resection.

CT scan can also be used to evaluate femoral version/torsion (additional cuts through the distal femoral condyles required) and acetabular version.5

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Sports hernia/athletic pubalgia/core muscle injury

Lumbar spine pathology

Gynecologic or urologic pathology

Intra-abdominal pathology

Hip flexor pathology or iliopsoas snapping

Iliotibial band pathology or snapping

Other extra-articular myotendinous pathology

Abductor/gluteus medius/minimus pathology

Pelvic stress fracture

Apophysitis or apophyseal injury in the developing skeleton

Intra-articular pathology not related to FAI

Extra-articular hip impingement

Neurogenic disorders

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative management of FAI consists of activity modification; avoiding painful activities such as deep hip flexion, aggressive hip flexion-based weight training, and other athletic activities that aggravate symptoms; and anti-inflammatories/analgesics and intra-articular injection in select cases.

Intra-articular pathology often progresses without symptoms early in the disease, and there is concern that without surgical treatment, significant labrochondral injury and arthritis might eventually develop, particularly in large camtype deformities.

Nonoperative management may be best employed in the already degenerative hip with joint space narrowing prior to total hip arthroplasty or milder deformities in patients willing to modify activities and consists of activity modification, core trunk strengthening exercises, and occasional intra-articular corticosteroid or hyaluronic acid injections.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Physical examination and imaging studies consistent with FAI

Pain despite activity modification

Pain in patients who are unable or unwilling to modify activity

Minimal to no degenerative changes

Arthroscopic versus open procedure for FAI (Table 1)

There are no strict indications for open versus arthroscopic management of traditional FAI, and decisions are typically made on the ability of the surgeon to correct the deformities with a given approach.

Posteriorly based femoral deformities, extra-articular trochanteric -pelvic impingement, and cases of mixed FAI/dysplastic anatomy with a predominance of instability findings are better served with open corrective procedures.

Table 1 Guidelines for Arthroscopic versus Open Repair of Femoroacetabular Impingement

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access