Scapulothoracic Arthroscopy

Ryan J. Warth

Peter J. Millett

DEFINITION

Scapulothoracic bursitis and snapping scapula syndrome are rare conditions characterized by periscapular pain with or without mechanical crepitus.

Scapulothoracic crepitus was first described by Boinet6 in 1867.

The resultant crepitant sounds were originally described as froissement, frottement, and craquement in 1904 by Mauclaire.21

Milch24 differentiated the sounds produced by soft tissues (frottement) and those produced by osseous or fibroosseous lesions (craquement).

ANATOMY

Bony anatomy

The scapula spans superoinferiorly from the second to the seventh rib and is connected to the axial skeleton via the acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joints.

The scapula is composed of borders (medial, lateral, and superior) and four angles (inferomedial, medial, lateral, and superomedial) which serve as important arthroscopic landmarks.

The scapula is concave on its anterior surface as it articulates with the convex thoracic cage.

The osseous anatomy of the scapulothoracic articulation can vary considerably,1 although some of these nonpathologic variations may be related to snapping scapula39:

Increased concavity of the medial scapular border39

Superomedial hooking12

Teres major tubercle39

Thickened superomedial and inferomedial angle1

The suprascapular notch occurs just medial to the take-off of the coracoid process and its shape has been categorized into six types (I-VI) by Rengachary34:

Type I (8%)—no notch is present.

Type II (31%)—notch is V-shaped and medially placed.

Type III (48%)—notch is U-shaped and has been found to be associated with suprascapular nerve entrapment.2

Type IV (3%)—notch is very small and V-shaped. The suprascapular nerve travels in a groove adjacent to the notch.

Type V (6%)—notch is U-shaped with ossification of the transverse humeral ligament.

Type VI (4%)—complete ossification of transverse humeral ligament leaving a foramen through which the suprascapular nerve travels.

The transverse scapular ligament, which spans the suprascapular notch, can also vary in morphology. There are three types as described by Polguj et al33:

Fan-shaped (55%)

Band-shaped (42%)—more likely to result in nerve entrapment

Bifid (3%)

Muscular anatomy

Trapezius muscle

Originates from the cervical and thoracic spinous processes and inserts along the superior aspect of the scapular spine

Innervated by the spinal accessory nerve along its deep surface

Serratus anterior muscle

Originates from the ribs and inserts on the anterior aspect of the medial scapular border

Innervated by the long thoracic nerve along its anterior surface

Subscapularis muscle

Originates within the subscapular fossa on the anterior surface of the scapula and inserts into the lesser tuberosity of the proximal humerus

Innervated by the upper and lower subscapular nerves along its anterior surface

Levator scapulae muscle

Originates from the spinous processes of the cervical spine and inserts along the medial border of the scapula

Innervated by the dorsal scapular nerve

Rhomboid major muscle

Originates from the upper thoracic vertebrae and inserts along the medial border of the scapula

Innervated by the dorsal scapular nerve

Rhomboid minor muscle

Originates from the lower cervical and upper thoracic spinous processes and inserts along the medial border of the scapula at the base of the scapular spine

Innervated by the dorsal scapular nerve

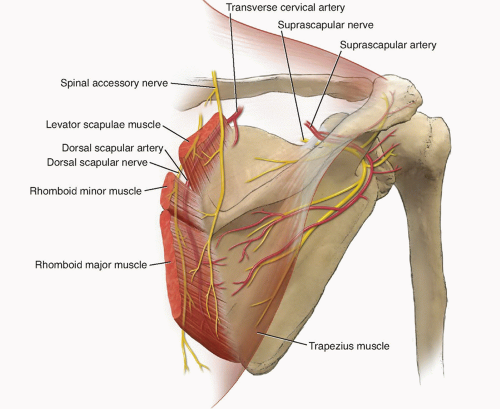

Neurovascular anatomy (FIG 1)

A thorough understanding of surrounding neurovascular structures is necessary to prevent iatrogenic injury.

The dorsal scapular nerve and artery run superoinferiorly 1 to 2 cm medial to the medial scapular border and deep to the rhomboid musculature (Ruland). Portal placement less than 3 cm from the medial scapular border endangers these structures.

The spinal accessory nerve is located in the central portion of the levator scapulae muscle deep to the trapezius muscle.36 Portal placement superior to the level of scapular spine endangers this structure.

FIG 1 • Illustration of neurovascular anatomy and safe portal position around the scapulothoracic articulation.

The long thoracic nerve travels along the anterior belly of the serratus anterior muscle. This nerve is infrequently in danger unless portals are placed in an extraordinarily lateral position.

The suprascapular nerve branches from the brachial plexus and runs posterosuperiorly with the suprascapular artery. The nerve passes through the suprascapular notch below the transverse scapular ligament, whereas the artery passes above this ligament. These structures are endangered with superomedial portal placement or when superomedial scapular resection is performed. It is important to place arthroscopic portals 2 to 3 cm lateral to the suprascapular notch to avoid iatrogenic injury.1,4

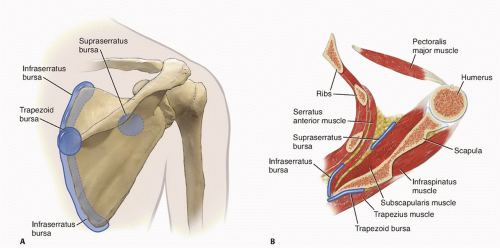

Bursal anatomy (FIG 2)

Anatomic bursae

Nonpathologic bursae that occur normally to allow gliding of surfaces in and around the scapulothoracic articulation

The infraserratus bursa lies between the anterior surface of the serratus anterior muscle and the posterior chest wall to allow gliding between these two structures (Kuhne).

The supraserratus bursa lies between the anterior surface of the subscapularis muscle and the posterior surface of the serratus anterior muscle to allow gliding between these two structures.18

Adventitial bursae

Symptoms occurring at the inferomedial angle are most likely caused by the presence of pathologic bursal tissue between the serratus anterior and the posterior chest wall.24,37

Symptoms occurring at the superomedial angle are thought to result from the presence of pathologic supraserratus or infraserratus bursae.11,17

Symptoms occurring at the medial base of the scapular spine are most often caused by a pathologic scapulotrapezial bursa located deep to the trapezius muscle near the junction of the medial border and the scapular spine.

Biomechanics

Smooth scapulothoracic stability and motion occurs as a result of the coordinated contraction of periscapular musculature and the function of various bursae that lie within muscular planes to allow gliding between surfaces. The scapulothoracic articulation effectively positions the glenoid to maximize range of motion capacity at the glenohumeral joint.

PATHOGENESIS

Scapulothoracic disorders result from abnormal stresses in the presence of predisposing anatomic variation.

Bursitis

Most commonly arise as an overuse syndrome of the shoulder

Bursal tissue becomes irritated when gliding over uneven surfaces.

Most commonly occurs at the superomedial, medial, and inferior angles of the scapula

Snapping scapula

Most commonly results from soft tissue entrapment between the scapula and underlying thorax. Very uncommonly, snapping scapula can also be due to an osseous or soft tissue mass with or without concurrent bursitis. Crepitus can also occur in asymptomatic individuals; thus, it should not be considered pathologic unless accompanied by pain and/or shoulder dysfunction.

Masses are rare in clinical practice. However, the most frequent scapulothoracic masses that result in crepitation include osteochondromas at the superomedial angle,13,40 elastofibroma dorsi8 at the inferomedial angle, and chondrosarcoma (especially in older patients). Resection of these masses is curative in the majority of cases.13,40

Other mechanical causes of “snapping” include bursal fibrosis,23,24 malunion of scapular or rib fractures,38 variations in anatomy of the scapula or posterior chest wall,1,12,39 scoliosis/kyphosis,20 first rib resection,41 and, rarely, anomalous musculature.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree