Scaphocapitate Fracture-Dislocation

13.1 Introduction

Combined fractures of scaphoid and capitate are erroneously characterized as scaphocapitate syndrome, but this is only one manifestation of a wide spectrum of injuries. The term “scaphocapitate syndrome” refers to associated fractures of the scaphoid and capitate with rotation of the head of the capitate by 90° to 180°.

The first references to a combination of scaphoid and capitate fractures in the context of a greater arc injury were made by Lorie and Perves in 1937.1,2 However, the term “naviculocapitate fracture syndrome” was introduced by Fenton3 in 1956, who described two patients with concomitant fractures of the scaphoid and capitate, in whom the proximal capitate fragment was rotated by 180° but their wrists were reduced. Since then, Hamdi4 in 2012 and Inal et al5 in 2009, after reviewing the literature, reported 43 and 47 cases of Fenton’s syndrome, respectively.

13.2 Incidence

The frequency of scaphocapitate syndrome is not clearly known. Rand et al6 reported that capitate fractures accounted for 1.3% of all carpal fractures; 0.3% were isolated capitate fractures; 0.6% were of scaphocapitate syndrome type; and 0.4% were fractures of the capitate in association with perilunate fracture dislocation (PLFD) injuries. Herzberg et al7 reported that in the transscaphoid PLFD group, the most frequent variant was the transscaphoid, transcapitate type, constituting 8% of all PLFD injuries.

In our series, from 53 cases of transscaphoid PLFD we found 10 cases of associated fractures of the scaphoid and capitate (5 with the wrist dislocated and 5 in the form of scaphocapitate syndrome). In addition, 1 out of 15 cases of PLFD with intact scaphoid exhibited a fracture of the capitate neck and rupture of the scaphotrapeziotrapezoid and lunotriquetral ligaments.

13.3 Mechanism of Injury

Fenton1 assumed that during a fall with the hand in dorsiflexion and radial deviation, the pointed radial styloid process (the chisel) impinges on the waist of the scaphoid, which is supported by the sturdy capitate (the anvil). When the force is moderately strong, the scaphoid alone will fracture, but when the blow is particularly sharp and violent, the capitate will also fracture.

Although a direct blow to the dorsum of the volar-flexed wrist has been implicated, most authors agree with the mechanism proposed by Stein and Siegel8 based on anatomical studies on cadaver wrists, according to which the patient falls on the outstretched hand and the wrist goes into marked dorsiflexion. The capitate fracture is caused by the impaction of the capitate neck to the dorsal lip of the radius, while the scaphoid fracture is caused by the tension created at the midcarpal joint level by the forced extension. We can reasonably assume that capitate fracture chronically precedes the scaphoid fracture. Rotation of the proximal fragment appears to occur secondarily, forced by the distal fragment, as this returns to a neutral position.

13.4 Spectrum of Injuries: Classification

The spectrum of injuries associated with fracture of the capitate neck is broad, ranging from an isolated, undisplaced fracture to a fracture of the capitate neck in the context of a fully developed greater arc injury (transscaphoid, transcapitate, transhamate, transtriquetral fracture-dislocation).

There is some confusion in the literature regarding the terminology due to the diversity in the appearance of these injuries. Any misunderstanding could be addressed if it were agreed that the term “scaphocapitate syndrome” should be used only in cases of a reduced wrist, with concomitant fractures of the scaphoid and the neck of the capitate and with its proximal pole rotated by 90° to 180°.

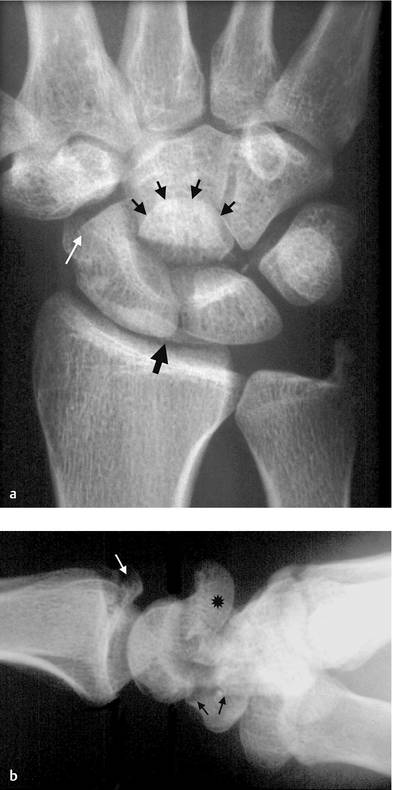

The two most common presentations with which a fracture of the capitate neck is manifested are a classic scaphocapitate syndrome (▶ Fig. 13.1a, b) and a combination of scaphoid and capitate fractures accompanying a dorsal perilunate dislocation (▶ Fig. 13.2a, b).

Fig. 13.1 A case of classic scaphocapitate syndrome with atypical fracture of the scaphoid. In PA view (a) the black arrows indicate the inverted articular surface of the proximal capitate fragment, the fractured dorsal radial rim is indicated with the single black arrow, while the white arrow indicates the fracture of the distal scaphoid that could be easily overlooked; in L view (b) the head of the capitate is dorsally displaced and rotated by 180° (asterisk), the white arrow indicates the fractured dorsal radial rim, while black arrows indicate the distal and volar location of the scaphoid fracture.

Fig. 13.2 A case of transscaphoid, transcapitate, transtriquetral dorsal perilunate fracture dislocation. The PA view (a) shows the displaced fragments of the scaphoid, the displaced fragment of the proximal capitate (asterisk), and the fractured triquetrum (double arrow); the L view (b) shows the dorsal displacement of the distal capitate, while the head of the capitate (asterisk) is dorsally displaced, rotated by 180°, and facing distally.

Some authors believe that scaphocapitate syndrome constitutes the final stage of a greater arc injury.9,10 The injury is considered to be a transscaphoid, transcapitate perilunate injury, which appears with the wrist being dislocated or reduced, spontaneously or after closed reduction. The wrist can be reduced but the capitate head remains displaced, with its proximal pole rotated by 90° to 180°.

Rarely, the combination of scaphoid and capitate fractures is encountered in cases of volar perilunate dislocations, whereas the injury is more extensive when the lunate is dislocated.9

Although the combination of capitate and scaphoid fractures is the most frequent, there have been reports in which the fractures of the scaphoid and capitate were associated with fractures of the distal radius,5 the lunate,10 the triquetrum,11,12 or the hamate.13 In a few cases of scaphocapitate fractures, the proximal capitate fragment was displaced volarly, causing median nerve compression.6,14 In rare cases, fractures of the capitate instead of the scaphoid were associated with fractures of the triquetrum15 or the hamate.

The head of the capitate deprived of ligamentous attachments displays a wide range of displacements after a fracture through its neck. If this is understandable in combined injuries, it is hardly obvious in isolated fractures, where the capitate is well protected from injury by its central location within the wrist. Hence, even in isolated fractures, the proximal fragment has been reported to be inverted by 180°, remaining in the concavity of the lunate,16 or displaced dorsally17 or volarly with various degrees of rotation.

The seemingly isolated but displaced fracture of the neck of the capitate requires scrupulous evaluation to exclude any osseous or ligamentous injuries on the radial and/or ulnar side of the wrist, which are not detectable by simple radiographs,16 for example, subtle fractures of the distal scaphoid (▶ Fig. 13.1a, b) or ruptures of the scaphotrapeziotrapezoid18 and/or lunotriquetral ligament.

The great variety of displacement of the head of the capitate is observed in cases where the fracture line is located at the level of the head or neck of the capitate. However, when the fracture line is located more distally, involving the body of the capitate (i.e., distal to the attachment of the scaphocapitate ligament), then the proximal fragment of the capitate may be displaced in association with the distal scaphoid in the same direction, as in the case presented by Kim et al.9

Vance et al14

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree