5 Safety and HVLA thrust techniques

Introduction

There are risks and benefits associated with any therapeutic intervention. High-velocity low-amplitude (HVLA) thrust techniques are distinguished from other osteopathic techniques because the practitioner applies a rapid thrust or impulse. Thrust or impulse techniques are considered to be potentially more dangerous when compared with non-impulse mobilization.

Complications

Incidence

There is wide variation in estimated serious adverse reactions arising from cervical manipulation. Various authors have attempted to estimate the incidence of iatrogenic stroke following cervical spine manipulation.1–14 Estimates vary from one incident in 10 000 cervical spine manipulations to one incident in 5.85 million cervical spine manipulations. Rivett and Milburn12 estimated the incidence of severe neurovascular compromise to be within the range one in 50 000 to one in 5 million cervical spine manipulations. Other authors estimate complications for cervical spine manipulation to be 1.46 times per 1 million manipulations15 and 1 case of cerebrovascular accident in every 1.3 million cervical treatment sessions increasing to one in every 0.9 million for upper cervical manipulation.9 Dvorak and Orelli3 report a rate of one serious complication per 400 000 cervical manipulations while Patijn11 found an overall rate of one complication per 518 886 manipulations. Miley et al14 estimated the incidence of vertebral artery dissection attributable to cervical spine manipulation as 1.3 cases for every 100 000 persons less than 45 years of age within 1 week of manipulation. The published research does not make clear which types of neck manipulation technique were applied, or the competence and training of the practitioner.16

Published figures may not accurately reflect the true incidence of serious cervical spine complications.10–12,17–19 The frequency with which complications arise in patients receiving cervical spine manipulation can only be an estimate as the true number of manipulations performed and the numbers of patients receiving cervical manipulation remain unknown.20 In relation to vertebral artery dissection, Haldeman et al21 indicate that a database of multiple millions of cervical manipulations are necessary to obtain accurate statistics. Such a complication can arise from normal neck movements and trivial trauma and not only from cervical manipulation.21–28 Haldeman et al21 reviewed the published literature to assess the risk factors and precipitating neck movements causing vertebrobasilar artery dissection. A total of 367 cases were identified, of which 252 were either of spontaneous onset, or related to trivial (Table 5.1) or major trauma. Less than one-third of cases (115) were associated with cervical manipulation.21 Haneline and Lewkovich23 undertook a literature search of the MEDLINE database for published articles relating to cervical artery dissection between 1994 and 2003. Twenty studies met the selection criteria reporting 606 cervical artery dissection cases. The authors concluded that a minority of cases was associated with cervical spine manipulation. A summary of the findings is outlined in Box 5.1.

Table 5.1 Description of trivial trauma associated with vertebrobasilar artery dissection / occlusion cases

| Type of trivial trauma | Examples | No. of cases |

|---|---|---|

| Sporting activities | Basketball, tennis, softball, swimming, callisthenics | 18 |

| Leisure activities | Walking, kneeling at prayer, household chores, sexual intercourse | 8 |

| Sustained rotation and / or extension | Wallpapering, washing walls and ceilings, archery, yoga | 10 |

| Short-lived rotation and / or extension | Turning head while driving, backing out of driveway, looking up | 7 |

| Sudden head movements | Sneezing, fair ride, violent coughing, sudden head flexion | 7 |

| Miscellaneous, minor trauma | Minor fall, ‘banging’ head | 2 |

| Miscellaneous | Atlanto-axial instability, postpartum, post gastrectomy | 6 |

| Total | 58 | |

Haldeman et al.21

Box 5.1 Aetiology of cervical artery dissections

• 54% internal carotid artery dissection

• 46% vertebral artery dissection

• 61% classified as spontaneous

• 30% associated with trauma / trivial trauma

(Reproduced with permission from Haneline et al.23)

Difficulties arise in the estimation of risk for vertebrobasilar dissection after neck manipulation, as patients may in fact seek treatment for symptoms of a progressing dissection.28 Smith et al29 attempted to address this issue in a case controlled study of the association between neck manipulation and cervical arterial dissection and reported that neck manipulation is an independent risk factor for vertebral artery dissection even after controlling for neck pain. A population-based, case control and case crossover study identified that primary care physician visits and attendance for chiropractic treatment for headache and neck pain were both strongly associated with subsequent vertebrobasilar artery stroke when compared with age- and gender-matched controls.28 This raises the possibility that patients with a symptomatic vertebral artery dissection seek clinical care prior to progressing to a vertebrobasilar stroke. Williams et al30 indicate that estimates for stroke following neck manipulation will always be difficult to quantify. Selection, referral and recall bias in addition to age-related variables have the potential to confound estimation of the risk of vertebrobasilar dissection after neck manipulation.30,31

The majority of published articles on complications of spinal manipulation have focused upon vascular consequences but non-vascular complications following spinal manipulation have also been documented.32 Serious complications are extremely uncommon and adverse consequences such as worsening lumbar disc herniation or cauda equina syndrome were found to be extremely rare in five systematic reviews of spinal manipulation.33 A systematic review of 73 randomized clinical trials reported no serious complication from spinal manipulation.34 A systematic review of the safety of spinal manipulation in the treatment of lumbar disc herniations reported the risk of a patient suffering a clinically worsened disc herniation or cauda equina syndrome following spinal manipulation to be less than 1 in 3.7 million.35 Although it is recognized that spinal manipulation is not without some risks, Haldeman has commented that it should be considered one of the safest forms of treatment available for spinal disorders.36

Classification of complications

Transient

Transient side-effects following cervical spine manipulation are relatively common.37 Less common transient reactions include dizziness or imbalance, extremity weakness, ringing in the ears, depression or anxiety, nausea or vomiting, blurred or impaired vision, confusion or disorientation.38

Transient side-effects resulting from manipulative treatment may be more common than one might expect and may remain unreported by patients unless information is explicitly requested. Prospective studies report common side-effects resulting from spinal manipulation occur between 30% and 61% of patients.39–43 These side-effects usually begin within 4 hours and resolve within the next 24 hours.41

Hvla Thrust Techniques And Relative Risks

Most of the research and reporting of both transient and more serious complications of manual interventions has focused upon HVLA thrust techniques. The incidence of complications of other manual therapy techniques remains largely unknown. Non-thrust techniques have also been associated with serious adverse consequences. Spontaneous intracranial hypotension has been reported secondary to a dural tear following cervical and thoracic spine mobilization.44 One case of cerebrovascular accident that only partially recovered and six cases of brachialgia with neurological deficit have been reported following cervical spine mobilization.45 A case of retinal artery occlusion followed ‘low-force joint mobilization from C2 to C7’46 and cerebral artery embolism has been attributed to Shiatsu massage.47 An internal carotid dissection followed use of a handheld electric massager.48 An attitudinal study of Australian Manipulative Physiotherapists who had undertaken specific postgraduate study in manipulative therapy reported that 84.5% used manipulation in the cervical spine and that most adverse effects associated with examination or treatment of the cervical spine arose as a result of passive mobilizing and examination techniques ahead of high-velocity thrust techniques.49

Many patients with musculoskeletal conditions are prescribed non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication. Dabbs and Lauretti50 reported the incidence of bleeding or perforation following the use of such medication for the treatment of osteoarthritis as being 4 in 1000 patients with death occurring in 4 out of 10 000 patients. The authors conclude that the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication when compared with cervical manipulation, for the treatment of comparable conditions, poses a significantly greater risk of serious complications and death. A national prospective survey in the United Kingdom of 19 772 patients receiving 50 276 cervical spine manipulations identified that the risk rates of cervical manipulation were comparable to the use of anti-inflammatory medications commonly prescribed for musculoskeletal conditions.37

Acupuncture is also used for the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions and is recognized to be a very safe therapeutic intervention in the hands of a competent practitioner.51 When comparative risk rates are considered those associated with neck manipulation are reported to be lower than those for acupuncture treatment.37

Many interventions for the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions are associated with risk but we do not have comparative risk rates compared with HVLA thrust techniques. Myocardial infarction following exercise prescription, allergic reactions to injection therapies, burns from heat, cold and electrotherapy are all well recognized as potential complications.

Even though the documented risk of stroke and death related to cervical spine manipulation appears to be less than other risks encountered in daily life, it is still considered legally pertinent to discuss risk with the patient.52 If one considers the risk of stroke or death following neck manipulation to be in the mid range of documented figures then the risk is comparable to a patient being involved in a serious plane crash with 0.75 air crashes (hull losses) reported per million departures in 2007.53 Patients can be informed that they are far more likely to die or be seriously injured in a motor vehicle accident than following cervical spine manipulation.

Contraindications

Whenever a practitioner applies a therapeutic intervention, due consideration must be given to the risk–benefit ratio. The benefit to the patient must outweigh any potential risk associated with the intervention. Contraindications or red flags can be classified as general or region specific and are identified from the patient’s history, physical examination and clinical tests.54 Contraindications have been classified as absolute and relative. The distinction between absolute and relative contraindications is influenced by factors such as the skill, experience and training of the practitioner, the type of technique selected, the amount of leverage and force used, the age, general health and physique of the patient.

Absolute

Relative

• Adverse reactions to previous manual therapy

• Anticoagulant or long-term corticosteroid use

• Advanced degenerative joint disease and spondylosis

• Psychological dependence upon HVLA thrust technique

• Ligamentous laxity / hypermobility

The above list is not intended to cover all possible clinical situations. Patients who have pathology may also have coincidental spinal pain and discomfort arising from mechanical dysfunction that may benefit from manipulative treatment.

Hvla Thrust Techniques And Disc Lesions

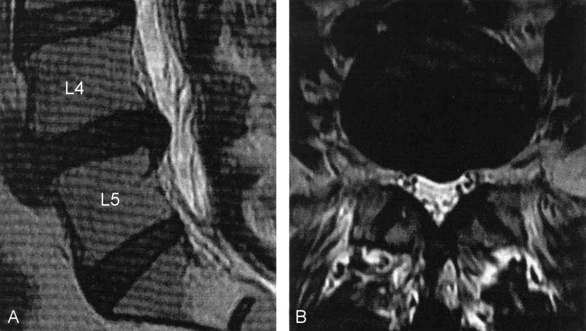

The diagnosis of disc pathology is achieved by clinical examination and imaging modalities including computerized tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 5.1)55. A number of studies have reported imaging evidence of a disc abnormality in asymptomatic individuals.56–62 Another study has reported patients with low back pain and imaging evidence of disc abnormality responding favourably to manipulative treatment without any alteration in the MRI findings.63 Abnormal disc imaging findings may frequently be coincidental to a patient’s symptoms and are not reliable predictors for the presence, development or duration of spinal pain. It has been reported that a high rate of asymptomatic subjects have disc herniation on MRI imaging and that clinicians need to be aware that MRI images are not necessarily a causal explanation of a patient’s pain.62 The diagnosis of discogenic pain should not be made from imaging findings alone but must also take into account a patient’s age, clinical signs and symptoms.

The use of HVLA thrust techniques for patients with disc bulging or herniation is often cited as being controversial but many authors do support the use of manipulation.63–69

One study of 27 patients with MRI documented and symptomatic disc herniation of the cervical and lumbar spine reported that 80% of subjects achieved a good clinical outcome, which suggests that chiropractic care including spinal manipulation may be a safe and effective treatment approach for patients presenting with symptomatic cervical or lumbar disc herniation.66 Other studies have also reported symptomatic benefits associated with spinal manipulation in patients with disc lesions.63,66,68,69

A review of the published data on the efficacy of spinal manipulation in the management of disc herniation, including published data on harms, reported that adverse events appear to be rare and manipulation is likely to be safe when used by appropriately trained practitioners.70 However, there have been case reports of a ruptured cervical disc71 and lumbar disc herniation progressing to cauda equina syndrome following manipulative procedures.72,73 What is not known is whether the disc herniation would have progressed without manipulation or whether the force and torque of the manipulation was a factor. A systematic review of the safety of spinal manipulation in the treatment of lumbar disc herniations reported the risk of a patient suffering a clinically worsened disc herniation or cauda equina syndrome following spinal manipulation to be less than 1 in 3.7 million.35 A systematic review of HVLA thrust techniques concluded that the evidence does not support the hypothesis that spinal manipulation is inherently unsafe in cases of symptomatic lumbar disc disease.74

The use of manipulation techniques under general anaesthesia for low back pain is associated with an increased risk of serious neurological damage.72 There is no evidence that this approach for the treatment of low back pain is effective.75

Cervical Artery Dysfunction

Adverse events can be associated with compromise of the cervical arterial system. Dissection within the cervical arteries is a recognized cause of ischaemic stroke in the young and middle aged.76,77 Definitive risk factors for vertebral artery and carotid artery dissection have not been identified. Vascular complications in these vessels can present with neck and head symptoms without the commonly described symptoms associated with vertebrobasilar insufficiency. Cervical artery dissection should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with headache and / or neck pain.78,79 Both the vertebral and internal carotid arteries should be considered in pre-treatment risk assessment.

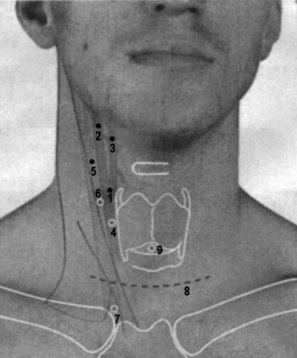

The common carotid artery is easily palpable in the neck above the sternocleidomastoid muscle. It divides into the internal and external carotid arteries at the level of the upper border of the thyroid cartilage (Fig. 5.2).80 The internal carotid artery extends directly upwards and through the base of the skull at the carotid canal of the temporal bone to supply the brain. The external carotid artery extends from the bifurcation of the common carotid artery to the neck of the mandible, there dividing into the superficial temporal and maxillary arteries.

Figure 5.2 Carotid arteries, internal jugular vein and applied anatomy.

4. Point of access to common carotid artery

6. Point of access to internal jugular vein above sternocleidomastoid muscle

7. Point of access of internal jugular vein between the heads of the sternocleidomastoid muscle

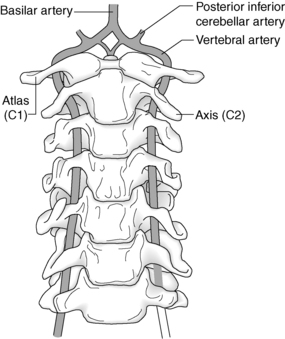

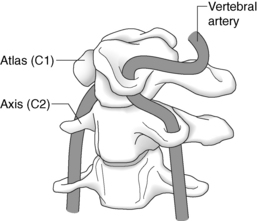

The vertebrobasilar system comprises the two vertebral arteries and their union to form the basilar artery (Fig. 5.3). This system supplies approximately 20% of intracranial blood supply.81 Blood flow in the vertebral artery may be affected by intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic factors, such as atherosclerosis, narrow the vessel lumen, increase turbulence and reduce blood flow. Extrinsic factors compress or impinge upon the external wall of the vertebral artery.

There are three areas where the vertebral artery is vulnerable to external compression:

1. At the level of the vertebral foramen of C6 by the contraction of the longus colli and / or the anterior scalene muscles.

2. Within the foramen transversarium between C6 and C2.

Vertebrobasilar Insufficiency

Diagnosis of VBI

For patients presenting with head and neck pain, especially sudden and severe symptoms, it is important to determine whether there is associated dizziness and / or signs of brain stem ischaemia such as nausea and / or vomiting. Dizziness is also a common presenting complaint with multiple aetiologies that must be distinguished from dizziness arising from VBI (Box 5.2). It has been suggested that questioning about nausea during VBI testing is as important as inquiring about dizziness.82 Diagnosed VBI is an absolute contraindication to HVLA thrust techniques to the cervical spine.