Rotational and Pedicle Flaps for Coverage of Distal Upper Extremity Injuries

L. Scott Levin

DEFINITION

A flap is a composite of tissue (ie, skin, fascia, muscle, bone, or combination) that is moved from its original location to another location in or on the body.5

Several different types of flaps exist, defined by their blood supply.

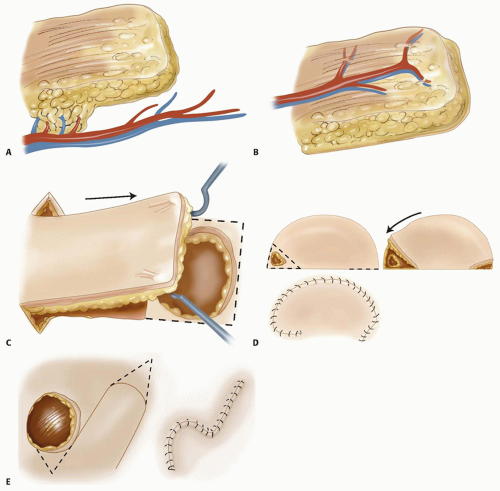

Random flaps (eg, Z-plasty, cross-finger flap) depend on preserving enough of the subcutaneous and dermal vascular plexus for flap survival. There are very few “random flaps.” Because of the extensive research on cutaneous circulation, the knowledge of vascular perforators, and understanding of angiosomes, this term is rarely used (FIG 1A).

Axial flaps depend on the blood supply from a single consistent (usually named) blood vessel; examples of this include the radial forearm flap and dorsal metacarpal artery flap (FIG 1B).

Free flaps depend on the division and microsurgical anastomosis of the artery and vein to reestablish blood flow to the flap in a different location.

Flaps also can be defined by how the tissue is moved.

Advancement flaps are elevated and advanced in a linear direction away from the base of the flap (FIG 1C).

Transpositional flaps are elevated and moved across normal tissue to a new defect site (FIG 1E).

Island flaps are elevated on their vascular pedicle and moved to a different location; mobility is limited by the pedicle length.

ANATOMY

A thorough understanding of the anatomy of the area injured and the donor area of the flap is necessary for safe elevation and insetting of these flaps.

A full description of the anatomy of the forearm and hand is beyond the scope of this chapter, but the key points of the relevant anatomy will be addressed in the separate sections.

The skin and soft tissue covering the forearm and hand vary by location, and this variation must be accounted for when considering coverage.

The palm (volar surface) of the hand consists of very thick dermis and epidermis that is structurally anchored to the underlying tissues by numerous vertical fascial connections.

The glabrous skin of the palm should be used to cover palmar defects, if possible.

The dorsum of the hand has thin dermis and subcutaneous fat covering gliding extensor tendons.

Coverage here should be as thin as possible to match the lost tissue.

Fingertip sensation and durability should be given consideration when deciding on the type of coverage for fingertip injury.

The forearm has thin soft tissue coverage.

Proximally there is muscle, which often can be covered with a skin graft.

Distally there is tendon on the palmar and dorsal surfaces. Trauma to the soft tissue often disrupts the paratenon and the exposed tendons will subsequently require flap coverage.

PATHOGENESIS

The mechanism of injury has a considerable effect on the need for flap coverage.

Sharp injuries can usually be closed primarily without the need for flap coverage.

Abrasive injuries commonly occur as a result of motor vehicle accidents. These usually involve one surface of the hand, and the extent of injury is usually relatively apparent. However, the level of contamination often is high, and extensive débridement of contaminated and devitalized tissue is necessary.

Crush injuries can lead to necrosis of skin, tendon, bone, and muscle. The zone of injury often is large and can be underestimated on initial inspection.

Other systemic injuries may delay treatment of extremity injuries. However, treatment for compartment syndrome and gross contamination must not be delayed any longer than necessary.

NATURAL HISTORY

The natural history of a wound depends greatly on the type of injury. The degree of original injury is the primary factor contributing to the prognosis for function of the hand.

A large wound involving the bones, tendons, or joints often has a profound negative effect on future function of the hand.

Early coverage can decrease total inflammation of the injured area and can limit the detrimental effect of the injury on the return to function.

Many wounds will heal by second intention without the need for coverage. Secondary healing can lead to acceptable results in some locations but also may lead to very poor results in others. These factors must be taken into account when deciding type of coverage.

Small wounds (<1 cm) on the fingertips, without exposed bone or tendon, will likely heal well on their own. This secondary healing often gives the strongest soft tissue coverage with the best sensibility and is the preferred treatment for most wounds of this type.

If dorsal hand wounds secondarily heal or “granulate” over tendons, the tendons tend to scar, which limits gliding and impairs finger motion.

Exposed bones, tendons, nerves, or vessels usually should be covered with a flap. Secondary healing or skin grafts will result in more scarring or unstable coverage.

Skin grafts are best for wounds that have no exposure of tendons, nerves, or vessels. However, in certain circumstances, a skin graft can provide temporary coverage over most viable tissue. Skin grafts will not survive on bone or tendon when the periosteum or paratenon is absent.

A well-performed flap will provide stable, durable coverage over any viable wound bed. This will allow earlier therapy and motion.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

After a traumatic injury, a complete history and physical examination are performed.

The mechanism of the injury is important. Contaminated or crush injuries often require more than one procedure for adequate irrigation and débridement.

Any past medical history of diabetes, smoking, heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, or hypercoagulability will impact the healing of any flap, but none of these is an absolute contraindication to coverage procedures.

Examination of the wound and extremity should be comprehensive:

Assessment of vascular status

Imaging for fracture

Motor and sensory examination to evaluate for nerve, tendon, or muscle injury

Examination for compartment syndrome in severe injuries

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Radiographs of the hand should be obtained to evaluate for bony injury.

Advanced imaging, such as computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), may be warranted for fracture pattern delineation, but these studies rarely are needed to assess the indications for flap coverage.

Questionable blood flow or limb perfusion warrants further evaluation, such as angiography.

Adequate blood flow to the extremity must be restored before considering flap coverage.

TYPES OF FLAPS

Radial Forearm Flap

This is a useful flap to cover upper extremity wounds. This flap can be used as a pedicle or free flap and provides excellent thin soft tissue coverage.9

The donor site is the major area of morbidity.

The volar forearm donor site is relatively conspicuous.

If a skin graft is needed to close the donor site, the donor morbidity is decreased by using nonmeshed split-thickness skin grafts applied carefully.

The radial artery is divided during isolation of the flap. Therefore, ulnar artery patency is critical. This must be confirmed with an Allen test or with direct Doppler evaluation of the hand with the radial artery occluded with manual pressure.

The flap can be elevated with a proximal (anterograde) or distal (retrograde or reversed) pedicle.

The anterograde flap is useful for coverage of the elbow, as either a pedicled flap or a free flap.

The reverse radial forearm flap can cover the volar and dorsal hand to and can reach the tips of the fingers.

The reversed radial forearm flap has arterial flow through the ulnar artery and palmar arches and back through the radial artery. The venous return is compromised due to valves in the vein but occurs through interconnections in the vena comitans that bypass the valves.

Advantages

Thin pliable tissue

Reliable anatomy

Fair color match

Can be elevated under tourniquet control

Disadvantages

Possible unsightly donor site

Requires patent ulnar artery

Reversed flap may appear swollen and slightly congested (but loss of flap is rare)

Relevant anatomy

The brachial artery divides in the proximal forearm to form the radial and ulnar arteries. The ulnar artery is the dominant arterial blood supply to the hand in most people.

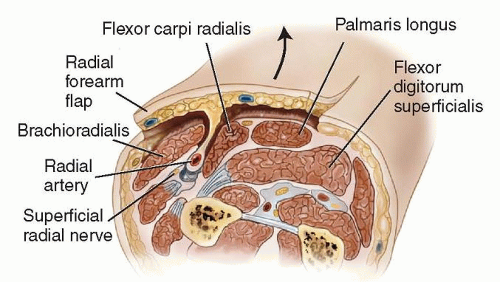

The radial artery courses distally just deep to the interval between the brachioradialis (BR) and the flexor carpi radialis (FCR) muscles. In the proximal forearm, the superficial branch of the radial nerve is adjacent to the radial artery.

The radial artery has paired venae comitantes that are important for venous egress from the flap once it is elevated.

There is a loose tissue septum between the FCR and BR. Within this septum, there are perforating branches of the radial artery to the skin that provide blood supply to the overlying skin. These are meticulously preserved to perfuse the flap (FIG 2).

Groin Flap

The groin flap is another commonly used pedicled flap for coverage of larger soft tissue avulsions of the hand.

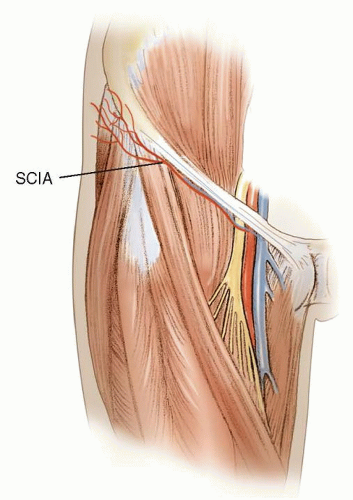

This fasciocutaneous flap is based on the superficial circumflex iliac artery (SCIA) and is located on the anterior thigh, just below the inguinal ligament.8

It can be taken as a free flap but more commonly used as a pedicled flap and a two-stage operation.

In the first stage, the flap is elevated laterally and inset onto the injured area. It is still attached medially by the pedicle originating from the femoral vessels.

In the second stage (2 to 3 weeks later), the pedicle is divided, freeing the arm from its connection to the groin.

Advantages

The flap is thin.

It is nearly hairless, which may or may not be an advantage, depending on the recipient site.

It is very reliable.

Flap elevation is relatively quick.

The donor site can be closed primarily with widths up to about 10 cm.

Disadvantages

Mandatory two-stage operation

The injured hand is dependent and connected to the patient’s groin for 2 to 3 weeks while waiting for vascular ingrowth.

Poor color match

Postoperative numbness in the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is common.

Relevant anatomy

The SCIA arises off the femoral artery about 3 cm inferior to the inguinal ligament and deep to the deep fascia of the thigh (FIG 3).

SCIA travels superolaterally beneath the deep fascia.

As the SCIA crosses the sartorius, it supplies branches to the muscle.

About 6 cm from the femoral artery, the SCIA travels superficial to Scarpa fascia.

Kite Flap

The kite flap, or first dorsal metacarpal artery flap, is a reliable flap taken from the dorsum of the index finger over the proximal phalanx.

Its most common use is for reconstruction of palmar thumb defects. Both soft tissue coverage and sensibility can be provided if the dorsal branches of the radial nerve are moved with the flap.1

It also can be used for web space reconstruction or covering smaller defects on the dorsum of the hand or wrist.

The flap can be 2 × 4 cm in size.

Relevant anatomy

The radial artery travels through the anatomic “snuffbox,” then onto the dorsum of the thumb, before diving between the two heads of the first dorsal interosseous muscle. This artery has three main branches:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree