Chapter 15 Rheumatology

Introduction

• Inflammatory arthritis includes rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, scleroderma, polymyositis, vasculitis, spondyloarthropathies and gout, with rheumatoid arthritis being the most common form of inflammatory arthritis. Inflammation may be seen in osteoarthritis, but this is due to a degenerative rather than an auto immune process.

• Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic unpredictable inflammatory disease of multifactorial origin; it is marked by a variable course, involving exacerbations and remissions of disease activity and often leads to joint damage and functional impairments.

• People often experience pain, joint stiffness, joint swelling, reduced muscle power, loss of joint range of motion, fatigue and extra-articular complications, which can lead to a significant loss of function and independence.

• Management should be patient-centred while taking into account each patient’s individual needs; therefore a thorough patient assessment must be completed before any treatment is undertaken.

• The multidisciplinary team (MDT) has been shown to be effective in optimising the management of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (SIGN 2000, Luqmani et al 2006) and patients should have access to all members of the team as necessary. There should be good communication and co-operation between all team members, as it may be necessary to refer onto another member of the team if the problems the patient is experiencing fall outside the scope of physiotherapy practice.

Aims of physiotherapy intervention

• Physiotherapy aims to reduce pain and stiffness, stabilise joints, prevent joint deformity, improve exercise tolerance and muscle power, maximise function, independence and quality of life and promote self management, by utilising a number of various treatment modalities available; education and exercise are the important active aspects of physiotherapy intervention (RCP 2009). Contraindications for each modality should always be considered.

Patient education and self management

• As with any long-term chronic condition, it is essential that patients undertake self management; patient education is therefore an important aspect in the management of rheumatoid arthritis, thus empowering patients to manage their own situation.

• Bandura (1977) in the theory relating to self-efficacy stated that: ‘the strength of belief in one’s own capacity is a good predictor of motivation and behaviour’. Within groups of rheumatoid arthritis patients, studies have shown that stronger self-efficacy correlates with better health status. It has also been found in some studies, that self-efficacy can reduce the number of visits to health care professionals (Cross et al 2006).

• Many rheumatology units will have a formal group patient education programme, these generally run at regular intervals throughout the year and involve various members of the MDT, who each deliver relevant information. Physiotherapists provide information related to exercise, function and self management strategies, e.g. goal setting, which can help to change patients behaviour (Barlow et al 2005). It has been reported this particular mix of education and advice can improve knowledge, self worth and early morning joint stiffness for up to 1 year post intervention (Bell et al 1998, Lineker et al 2001).

• Primary care trusts run the expert patient programmes for people with long-term chronic conditions and are not disease specific. The patients are facilitated to develop their communication skills, manage their emotions, manage daily activities, interact with the healthcare system, find health resources, plan for the future, understand exercising and healthy eating, and manage fatigue, sleep, pain, anger and depression (Department of Health 2006).

• Any patient contact can be used as an opportunity to enhance patient knowledge and understanding of their disease and self management and can be personalised for each patient, so that each individual has their specific needs met.

• Joint inflammation can cause tiredness and a general feeling of being unwell, therefore advice about pacing should always form part of a patient’s rehabilitation (Braun and Sieper 2006, Vlak 2004, Liu et al, 2004).

• Patient education has been shown to:

• Education should be made available in different languages and styles to suit the local population (Luqmani et al 2009).

Patient support groups

• Voluntary organisations such as National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society (NRAS), Arthritis Care and Arthritis Research UK (formally ARC), all provide excellent written information for patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

• Information on the NRAS and ARC sites are written by health professionals and are regularly reviewed to ensure up to date evidenced based and accurate information is provided specifically for UK residents (Luqmani et al 2009). The organisations provide help lines for patients and NRAS are able to put patients in touch with one another. It is seen to be helpful for patients with the disease to talk to others with the same condition.

• NRAS will also provide support for units to set up patient support groups; these are groups run by the patients for the patients and provide a continuous source of information and education, enabling patients to support one another. The format of the meetings tends to vary according to the population that attend the groups (www.nras.org.uk).

Exercise therapy

• Exercise is the foundation of physiotherapy and should be utilised and encouraged in the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

• Exercise therapy can be delivered on land or in water and research supports the use of aerobic activity, improving range of movement, muscle strengthening, stability (balance) and promotion of physical activity.

• When treating patients with a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, it is important to remember that studies have shown that this group of patients tend to be more sedentary and are at greater risk of cardiovascular disease, (Luqmani et al 2006, Sokka and Hakkinen 2008) and osteoporotic fractures than the non-rheumatoid arthritis population (Turesson and Matteson 2007).

• Loss of body cell mass has been described in rheumatoid arthritis (Rall & Roubenoff 2004). The reasons for weight loss in rheumatoid arthritis include factors such as mechanical problems leading to muscle wasting, poor appetite and the metabolic drain of the inflammatory response (Munro and Capell 1997).

• Many factors may lead to reduced activity in this population group including: joint pain and stiffness, loss of body cell mass and disuse of muscles leading to loss of strength and possibly a fear of causing damage through over activity.

• Patients with RA therefore may have reduced:

• In addition to its general effects of reduced risk of coronary heart disease, hypertension and diabetes, exercise has shown to improve function in rheumatoid arthritis. (De Jong et al 2004, Van den Ende et al 1998). Dynamic exercise, that is: exercise of sufficient intensity, duration and frequency to establish an improvement in aerobic capacity and/or muscle strength, has been shown to be efficient in increasing muscle strength and aerobic capacity in patients with stable disease (RCP 2009).

• For some time, it was thought that dynamic, active exercise would cause increased pain, prolong active disease and lead to joint destruction (Hurley et al 2002). There is evidence to show the usefulness and safety of dynamic exercise in the rheumatoid arthritis population. Self-management and exercise has been shown to improve physical and psychological wellbeing. Aerobic exercise is known to improve health related fitness, reduce pain and fatigue, and improve function without aggravating or hastening joint destruction. Joint range of motion and specific strengthening exercises are beneficial (RCP 2009). Most of the evidence is obtained from chronic stable rheumatoid arthritis patients. Recorded improvement in muscle strength, aerobic capability, endurance, function, self value and well being have followed participation in dynamic exercise (Hurley et al 2002).

• No adverse effects on the disease activity or pain have yet been observed (SIGN 2000).

• Patients with rheumatoid arthritis have an increased risk of developing both generalised and juxta-articular osteoporosis and associated osteoporotic fractures (Deodhar and Woolf 1996, Lodder et al 2004). Juxta-articular osteoporosis is thought to be due to an increase in local vascularity and direct invasion by the pannus; in addition, the inflammatory mediators are also implicated. Systemic inflammation and reduced mobility due to functional impairment (Deodhar and Woolf 1996) are thought to be factors which can lead to generalised bone loss. Weight-bearing exercise can be beneficial in helping to prevent bone loss and improve balance (De Jong et al 2004). Lemmey et al (2009) were able to demonstrate increased muscle mass, reduced fat mass and restoration of function in their study of supervised progressive resistance training.

• Exercises and exercise advice should be modified for each individual patient and can be adapted to aid functional activities in which the patient may be experiencing a particular difficulty.

• Exercise should be encouraged in patients with rheumatoid arthritis to reduce the risks that the disease can cause as outlined above. Exercise does not exacerbate disease activity or cause joint damage in the short term (Luqmani et al 2006).

• Exercise regimens have been shown to be more successful in patients where personalised contact with a health professional occurs, where the benefits of exercise can be discussed (RCP 2009). Government recommendations for the amount of exercises a healthy adult (16-64 hears old) should undertake is 30 minutes of moderate intensity (cycling or fast walking) on 5 days of the week (www.patient.co.uk).

Exercises to be included in a patient’s programme

Strengthening exercises

• To improve motor function, by maintaining or improving muscle strength, improve function and aid joint protection.

Aerobic, dynamic exercises

• To improve cardiovascular fitness, maintain optimal weight, maintain or improve function, improve psychological fitness and reduce pain and fatigue. It is also known to have a positive effect on function without exacerbating disease activity or causing joint damage in the short term.

• Aerobic exercise can include activities such as:

• Aerobic exercise should be carried out at low to medium intensity (SIGN), sufficient to increase the heart-rate to a higher level, allowing the patients to carry on a short conversation whilst exercising. Exercise that fits into the patient’s daily routine and something which they enjoy doing will help them to maintain their programme.

• Encourage patients to try something new. Local areas will usually have various exercise programmes for all abilities and interests; look at what is available locally.

• The amount of exercise will vary from patient to patient. Patients should develop and monitor their own progressive exercise programme.

• Patients should understand the importance of exercising so that they do not over- or under-exercise.

• It is important to build up exercise gradually, to prevent the possibility of causing increased joint pain, at the same time; patients should be advised about the increased muscle pain often associated with starting a new exercise. It is important to set appropriate goals with the patient before starting exercise.

Setting a baseline

• Prior to starting any exercise programme, a baseline will need to be determined.

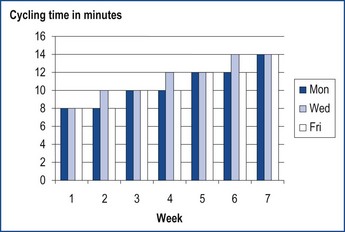

• Establishing a manageable baseline for exercise or activity can be achieved by asking the patient to decide for themselves how much exercise/activity will be suitable for them, e.g. cycling on a static bike for 8 minutes.

• The following day, the patient assesses how they feel following the exercise: Did I overdo it? Was it too easy?

• They will then adjust the exercise/activity, based on their own judgement; it might be more. For example cycling for 12 minutes on a static bike.

• The average time for the two days is then calculated, minus 20%.

• This will ensure that the exercise is manageable on days when the patient does not feel quite so good.

• Exercise can then be increased from this baseline, with the patient avoiding doing too much on a good day with the possible consequence of being unable to do much on the following day.

• The patient can then work towards their goal as per the following example:

• This ensures consistent and gradual increase in exercise.

• An alternative method is to work out using maximal heart rate.

• The recommended aerobic exercise is 60–85% of maximal heart rate for 30–60 minutes, 3 times a week.

• For patients to determine their baseline aerobic exercise capacity, they will need to subtract their age from 220, this will give them their approximate maximum heart rate, e.g. for a patient aged 55 years, 220 – 55 = 165 beats per min.

• If the patient has been fairly sedentary, it may be appropriate to suggest them working at 55% to 65% of that number during their exercise session, e.g. for a patient aged 55 years old, maximum heart rate is 165 (220 − 55), they would exercise for 20 to 30 minutes with their heart rate between 91 and 107 beats per minute:

Aquatic Physiotherapy in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis

• A working knowledge of Aquatic Physiotherapy, including safety issues, contraindications, precautions, how to utilise the properties of water and local guidelines is required before treating patients in a therapy pool (Bruckner & Khan 2005).

• Aquatic physiotherapy is one of the oldest and most frequently used treatment regimes for rheumatoid arthritis.

• In the long term Aquatic Physiotherapy has been shown to reduce hospital admissions and has few if any negative effects (Hurley et al 2002).

• It is essential that patients are assessed for contraindications to Aquatic Physiotherapy, which may prevent some patients with rheumatoid arthritis from accessing the modality.

• Clinically, patients can move more readily in water and are able to perform activities which they cannot perform on land, e.g. walking or muscle strengthening.

• Loading across joints is reduced by buoyancy which allows functional exercises to be undertaken (Harrison and Bulstrode 1987, Harrison et al 1992).

Joint protection

Joint changes

• Normal joints are stable because of the conformity of the bone ends, surrounding capsule and ligaments and the muscles and tendons that move the joint.

• Where there is frequent inflammation of a joint, the surrounding soft tissues become stretched, ligaments are disrupted and invasive pannus erodes cartilage and subchondral bone.

• The results of repeated inflammation are pain, joint stiffness, loss of muscle power, instability as a result of the joint erosion and ultimately deformity.

Process of joint protection

• Patients must be taught how to perform daily activities while placing minimal stress on joints in order to reduce pain, preserve joint structures and conserve physical energy.

• Altering the way, in which people perform certain jobs together with the use of aids and gadgets, can help to maintain independence and protect joints.

• The level of activity can be adjusted according to the level of pain the patient is experiencing. Where possible:

• Certain types of grip may present a risk to joints, a tight or prolonged pinch grip or a static grip (as in knitting), places an increased force on the MCP joint and the palm, pulling on the MCP joint, tight or prolonged static grips should be avoided.

• Exercise has an important role in joint protection and should be part of a daily routine, which will help to maintain range of movement, enhance muscle strength and promote general well being.

Fatigue and pacing

Fatigue

• Described as physical and mental weariness and can affect quality of life (Luqmani et al 2009).

• It has been reported that 40–80% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis experience fatigue day after day, irrespective of what they have been doing (Pollard et al 2006, Van Hoogmoed et al 2010).

• Disease activity is thought to be a factor in fatigue allied to other influences such as; pain, psychological and social factors, health beliefs and illness perception, there is also a suggestion that this may be centrally mediated (Pollard et al 2006).

Pacing

• Patients must find a balance between rest and activity by pacing themselves.

• The appropriate amount of rest and relaxation during daily activities can be significantly effective in helping patients to manage the disease.

• Advising patients to recognise their limitations is important, e.g. If an activity ‘feels like it’s too much’, then ‘it is too much’.

• Planning which jobs can be eliminated, made simpler, finding the most economical way of performing the activity, using gadgets and aids to assist or enlisting the help of others will all help in conserving energy for the things which are really important to the patient.

• Clinically, it is often difficult for patients to readjust to their disease particularly at the onset, as fatigue is often a problem and will influence the amount of activity undertaken.

• Exercise has been shown to improve physical fatigue as well as psychological wellbeing and self efficacy, encouraging exercise in this patient group allows them to take more responsibility for their own management (Luqmani et al 2009).

Managing a ‘flare’

• Rheumatoid arthritis is an unpredictable disease and many patients will experience times when their arthritis worsens, with increased pain and stiffness, this is often referred to as a ‘flare’ and can last from a few hours to several days. Patients may also experience increased fatigue, appetite loss and low mood during these periods.

• Patients need to be advised about a number of management strategies in order that they can choose what works the best for them.

• During a flare, patients should still move the affected joint(s) within a comfortable range of movement, several times a day, to relieve stiffness and maintain muscle tone.

• Force or resistance should not be applied to the affected part.

• If able, gentle exercise for the rest of the body can be carried out, ensuring that the activity is paced.

• If the wrists are affected, wrist splints may help to rest and support the joint, relieve pain and keep the wrist in a good functional position.

• Relaxation may be of benefit, but it can take practice. Patients can learn how to let go of physical muscle tension and release physical stress.

• Cool packs, for red, hot, swollen joints, or heat for painful joints can be used to relieve joint signs and symptoms.

• Some patients may find transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) useful.

• Establishing a good sleeping pattern may help reduce muscle tension and pain.

• Patient support groups provide excellent advice on coping with flares (Appendix 15.1).

The cervical spine in rheumatoid arthritis

• Cervical spine involvement is often seen in rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory diseases such as psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

• Joint, bone and ligament damage can lead to subluxations, which are reported to occur in 43–86% of all patients with rheumatoid arthritis (Roche et al 2002).

• There are indications that subluxations begin soon after the onset of disease.

• A study of patients admitted to hospital for hip or knee surgery showed that 61% had cervical instability and longitudinal follow-up at autopsy indicates that cord compression is the cause of death in approximately 10% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and cervical spine involvement (Luqmani et al 2009, Roche et al 2002).

• The severity of cervical spine involvement correlates with the duration and severity of the disease, resulting in varying degrees of instability in the cervical spine.

• Approximately 30% of patients with cervical instability will be asymptomatic and it may be difficult to detect signs of neurological deficit in the presence of a painful arthritis, with associated muscle atrophy or weakness (Luqmani et al 2006).

• Anterior atlantoaxial subluxation is the commonest form of subluxation seen in this patient group, followed by subaxial subluxation of the lower cervical vertebrae.

• Basilar invagination (or vertical subluxation) is the most dangerous form of subluxation and posterior and rotatory atlantoaxial subluxations are rare (Roche et al 2002).

Anatomical considerations

• Rotation of the head is performed at the atlantoaxial C1 atlas and C2 axis, vertebral segments.

• The odontoid peg (dens) acts as an axis of rotation and the odontoid peg is held against C1 by the transverse ligament, which runs from one side of C1 to the other.

• The odontoid peg prevents forward slipping of C1 on C2.

• Alar ligaments pass upwards and outwards to attach to the condyles of the occiput from either side of the odontoid peg.

• Synovial joint effusion, proliferation of synovial tissue together with osteoporosis combine to destroy the odontoid peg as well as the transverse and alar ligaments, resulting in atlantoaxial subluxation with concomitant/coexistent narrowing of the spinal canal.

• When the ligaments are damaged, the head will tend to pull the atlas away from the axis during flexion and cause the subluxation.

• Vertical subluxation (basilar invagination), as a result of destruction of the lateral atlantoaxial joints and atlanto-occipital joints leads to upward migration of the odontoid and surrounding pannus into the foramen magnum, compressing the brainstem and spinal cord.

• In these patients sudden death may occur after unexpected vomiting of physical trauma. Basilar-vertebral insufficiency may also occur in these cases, with syncope after flexion.

• Vertical subluxation and atlantoaxial subluxation may occur together.

• Patients may present with symptoms such as new cervical and/or head pain, C2 neuralgia or cervical spine stiffness.

• Hakkinen et al (2005), found that patients with atlantoaxial disorders had reduced muscle strength in flexion, extension and rotation.

• Treatment of rheumatoid cervical spine involvement is usually conservative.

• For patients who present with severe intractable pain or myelopathy, surgery is usually indicated (Choi et al 2006, Kauppi et al 2005).

• Diagnosis of cervical spine involvement is by plain X-ray, with lateral views of the cervical spine taken in full flexion and full extension (Kauppi and Neva 1998) and through the mouth views for C1/C2 specifically (Geusens et al, 2005).

• MRI is commonly used to assess the degree of degeneration in the articular cartilage.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree