Chapter 15 Rheumatology

Introduction

• Rheumatology covers a wide range of conditions affecting the musculoskeletal system including all types of arthropathies and soft tissue conditions such as tendonitis and bursitis.

• Also included are less common auto-immune conditions such as connective tissue disorders and vasculitis.

• Many long-term conditions can be managed by different specialist areas of physiotherapy.

• Chronic pain management may be managed by pain specialists in some geographical areas, whereas in others a rheumatology service will have the remit for managing chronic pain.

• Physiotherapy for rheumatological conditions is built upon the core skills that are used in all areas of musculoskeletal practice.

• This volume anticipates that the reader will possess a basic level of knowledge and experience of musculoskeletal assessment, i.e. that they will be able to carry out an assessment of joint range or muscle power.

• The material in the volume will guide the reader in how they may apply core skills in the assessment of patients with inflammatory arthritis.

Current trends in management of inflammatory arthritis

• The medical treatment of inflammatory arthritis is a rapidly developing area of healthcare.

• In the recent past there have been major advances in drug treatment offering significant improvements in long-term function and disease management within inflammatory arthritis.

• Whereas in the past a physiotherapist would expect to see large numbers of patients with significant disability levels, these are now being encountered less frequently.

• Due to these changes the role of the rheumatology physiotherapist is sometimes poorly understood and appreciated within the profession.

The purpose of assessment

Identification of potential case of currently undiagnosed inflammatory arthritis

• Increasing numbers of patients are choosing to self-refer to physiotherapy. This means that physiotherapists can often be a first point of contact for a patient with an undiagnosed rheumatological condition (Cleland and Walter-Venzke 2003).

• Early diagnosis and treatment is the basis of modern rheumatology, any suspected cases of new inflammatory arthritis should be referred to specialist services.

• Box 15.1 outlines the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance for the early referral of suspected new cases of rheumatoid arthritis (NICE 2009).

• It is important to ask specific questions during the assessment which can help identify the presence of inflammatory back pain.

• It is worth noting that with inflammatory arthritis of peripheral joints or the axial skeleton there is no single definitive diagnostic test which can be used; diagnosis is achieved through a combination of examination, considering the features that the patient presents with (Box 15.2), history taking and the appropriate application of specific diagnostic tests and techniques.

Box 15.2 Features of inflammatory arthritis

• Tender, warm, swollen joints

• Symmetrical pattern of affected joints

• Joint inflammation often affecting the feet, wrists and finger joints

• Joint inflammation affecting other joints, including the neck, shoulders, elbows, hips, knees, ankles, and feet

• Fatigue, occasional fevers, a general sense of not feeling well

• Pain and stiffness lasting for more than 30 min in the morning or after a long rest

• Symptoms that last for many years

• Variability of symptoms among people with the disease (NIAMS 2009)

Assessment and diagnosis of inflammatory arthritis

• This will be significantly influenced by the involvement of other health professionals, the phase of drug treatment the patient is in, the disease process, and ultimately the patient’s expectations and aspirations.

• Physiotherapists will invariably practice within a multidisciplinary team, usually comprised of:

Review assessment

• These tend to be undertaken as part of a regular planned review process of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis by a rheumatology team, in accordance with the NICE guidelines (NICE 2009).

• ASAS/EULAR recommend that the frequency of monitoring in ankylosing spondylitis (AS) should be decided for each individual patient based on symptoms and disease severity (Kiltz et al 2009).

Triage assessment

• This is a developing area for physiotherapists working within a rheumatology team. Additional training in specific diagnostic and therapeutic skills has expanded the role of the rheumatology physiotherapist in a way that has been established in orthopaedics for a number of years (Weatherley and Hourigan 1998, Pearse et al 2006).

Subjective assessment

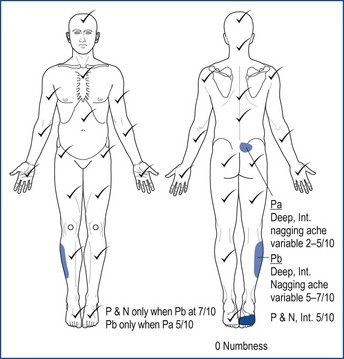

• It is important to record information on a body chart (Figure 15.1). This provides a baseline of the patient’s symptoms on the first attendance which should change in response to physiotherapy intervention.

• Central to the whole assessment process is the interaction between clinician and patient.

• At the beginning of an assessment it is essential to establish a rapport with the patient, provide explanations about what the assessment entails, and obtain their consent.

• Consent is an ongoing, interactive process that will need to be sought throughout the assessment and subsequent treatment (CSP 2005).

Patient-defined problems, health beliefs, expectations and mood

• Gaining an understanding of the impact of the condition on the patient’s function and lifestyle is crucial to the therapeutic process.

• This will have a direct bearing on the short- and long-term physiotherapy interventions and the patient’s undertaking of ‘self management’.

• A general evaluation of mood can be useful to consider if a patient seems depressed or anxious.

• Use of validated measures such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) may identify affected mood in appropriately selected patients (Zigmond and Snaith 1983).

• Function can be affected in inflammatory arthritis, causing some tasks to become difficult and others impossible (Table 15.1).

• A number of validated measures exist to evaluate this, for example the Health Activity Questionnaire (HAQ) (Fries et al 1980).

• At times it can also be useful to assess health-related quality of life using validated measures such as EQ5D (The EuroQoL Group 1990).

• Throughout the assessment it is necessary to consider how the various aspects of functional impairment relate to the underlying rheumatological condition and what is important to the patient.

• During any discussion of function it is important to identify how the skills of the physiotherapist may assist the patient with their functional activities and where other professions may have a role to play.

• Major functional limitation may entail referral to an occupational therapist. Good team communication and working is essential here.

Table 15.1 Potential functional impairments in rheumatological conditions

| Peripheral joints | Axial skeleton |

Pattern of joints affected by rheumatoid arthritis

• Inflammatory arthritis will typically develop a characteristic pattern of joint involvement.

• A rheumatology body chart can be used to record specific joint palpation finding (warmth, pain swelling).

• It can be useful to have larger hands because of the relatively high occurrence of arthritis in this area and therefore facilitate the recording of greater detail (Figure 15.2).

Behaviour of signs and symptoms

Swelling/temperature

• The pattern of painful and swollen joints in inflammatory arthritis can vary for the different types of arthritis.

• Given the often protracted nature of the problems before the assessment, patients can sometime lack precision in describing swelling and other features.

• A feature of the spondyloarthropathies is dactylitis (swelling of a whole digit), and in acute arthritis joints can appear warm.

Joint stiffness

• The stiffness associated with inflammatory arthritis is typically worse after periods of immobility.

• Significant times for this are getting out of bed in the morning, getting up after prolonged sitting and sustaining a fixed position.

• Morning stiffness of more than 30 minutes is an important diagnostic feature of inflammatory arthritis, but the stiffness duration can sometimes be shorter.

• In the context of discussing pain and stiffness it can often be helpful to take the patient through a typical day to allow them to highlight the variation in the symptom pattern, which in inflammatory arthritis will tend to be worse in the first half of the day.

Pain

• It is helpful to define the areas affected as precisely as possible. In arthritis the pain, stiffness and swelling often coincide within the same general area.

• In chronic rheumatological conditions pain may seem confusing because the patient may report pain associated with inflammation in a specific joint and also arising from secondary degenerative changes, other long-term but uninvolved conditions, or pain which might lack a specific physical cause.

• Noting the patient’s description of pain can help to determine the structures involved, e.g. sharp and shooting may indicate nerve root involvement.

• Note the behaviour of the pain in response to movement and activity, also the patient’s beliefs about their symptoms.

• Patients may also report pain and swelling at the entheses (the insertion of tendons into bone), known as enthesitis. If a spondyloarthropathy is suspected or diagnosed there is the possibility of enthesitis occurring (Colbert 2010). This can be assessed by careful palpation and using an enthesitis index Appendix 15.1. Experienced clinicians should be aware of false responses due to the natural discomfort of palpating these areas.

• It is important to differentiate between mechanical and inflammatory causes of back pain and therefore screening questions need to be included in the assessment to identify undiagnosed inflammatory back pain (Box 15.3).

Box 15.3

Screening questions for suspected inflammatory back pain

• Early morning stiffness, back and/or neck >30 min (mechanical back pain often lasts for a shorter time)

• Pain improves with exercise? (mechanical is often worse)

• Awake 2nd half of night with pain/stiffness?

• Age under 45 at onset? Frequently in twenties/thirties at onset (mechanical often has later onset)

• Close relatives with inflammatory arthritis?

• Better on gentle movement rather than rest? (mechanical often better at rest)

• Stiffness after sitting? (mechanical often increased pain on sitting relieved by standing)

• History of one or more the following might be present:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree