Rheumatic Heart Disease

Galal M. El-Said

Yasser M. K. Baghdady

Howaida G. El-Said

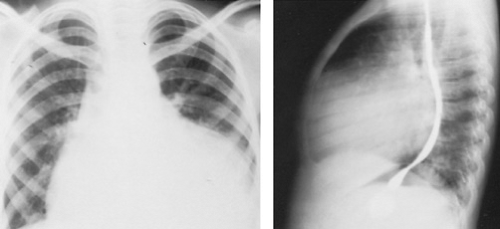

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD), like rheumatic fever, is seen more commonly in areas where the standard of living is low. RHD remains one of the leading causes of heart disease in developing countries, where rheumatic fever occurs commonly. It assumes malignant and chronic forms that can lead to significant valvular heart disease in childhood, often accompanied by significant pulmonary hypertension, and may require surgery at an early age (Figs. 286.1 and 286.2). In children and adolescents with RHD, the mitral valve is involved in 85% of the cases, the aortic valve in 55%, and the tricuspid and pulmonary valves in fewer than 5%.

RHEUMATIC MITRAL INSUFFICIENCY

Mitral insufficiency is the most common cardiac defect in children and adolescents with RHD. As the left ventricle (LV) contracts, part of its stroke volume regurgitates into the left atrium (LA) through the incompetent mitral valve. Because of the difference in pressure between the LV and LA, regurgitation starts during the isometric contraction phase.

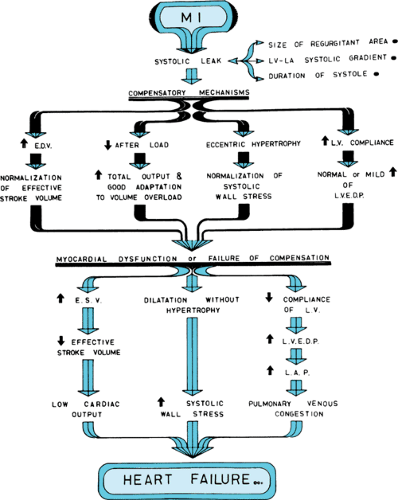

Compensation begins with dilation of the LV to accommodate the increased blood volume. In chronic mitral insufficiency, the increase in LV end-diastolic volume usually is not accompanied by increased end-diastolic pressure because of increased LV compliance. The increase in LV end-diastolic volume (i.e., increased preload) brings the Frank-Starling mechanism into play, which permits a large stroke output. Because the regurgitant mitral orifice is in parallel with the aortic orifice, the resistance to LV emptying is reduced (i.e., decreased afterload) (Fig. 286.3).

The compensatory mechanisms of increased compliance, increased preload, decreased afterload, and increased wall thickness are not sufficient to overcome persistent mitral insufficiency. Myocardial contractility becomes impaired because of the chronic volume overload. Symptoms of low cardiac output are followed by symptoms of lung congestion caused by LV failure (see Fig. 286.3).

Clinical Manifestations

Because symptoms usually do not develop until the LV is compromised, the interval between acquiring rheumatic fever and the development of symptoms of mitral insufficiency tends to be longer than that for mitral stenosis (MS), often exceeding 2 decades. Unlike MS, symptoms of low cardiac output (e.g., weakness, fatigue) are more prominent and appear before symptoms of lung congestion (e.g., exertional, nocturnal, or resting dyspnea; recurrent chest infections; hemoptysis).

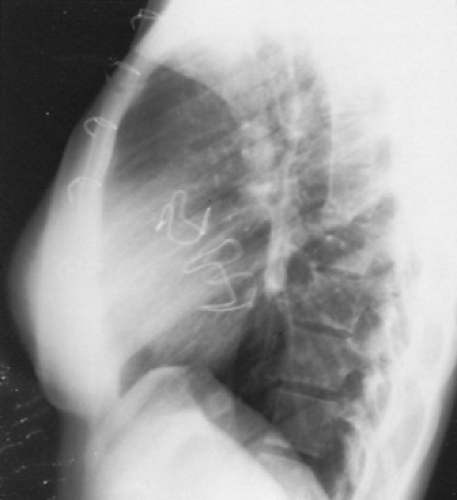

FIGURE 286.2. A lateral chest radiograph shows the mitral and aortic valve stents that were placed at a young age. |

The cardiac impulse is diffuse, forceful, and displaced downward and laterally. The first heart sound usually is diminished. A loud apical third heart sound usually is audible and is caused by the increased transmitral volume flow that occurs during the rapid filling phase. The characteristic murmur of mitral insufficiency is a high-pitched holosystolic murmur, beginning with the soft first sound and continuing to the second sound. The second heart sound sometimes is obscured by the murmur. The murmur is loudest at the apex, with radiation to the axilla and left infrascapular area.

Laboratory Findings

In chronic mitral insufficiency, the electrocardiogram exhibits evidence of enlargements of the LV and LA. Radiologically, the cardiac shadow is normal early in the course of the disease; later, LA and LV enlargements become evident.

Echocardiography is useful for identifying the cause and degree of mitral insufficiency and for evaluating LV function. M-mode echocardiography can show an increase in the LV diastolic dimension and a significant decrease in LV diameter during the preejection phase. The two-dimensional echocardiographic criteria for the diagnosis of rheumatic mitral insufficiency include thickened mitral valve leaflets, incomplete closure of the mitral valve, a relatively immobile posterior mitral leaflet, a dilated LA with systolic expansion, and a dilated LV with hyperdynamic septal and posterior wall motion. The degree of mitral insufficiency can be assessed using Doppler echocardiography, by determining the extension and intensity of the Doppler signal of the regurgitant jet in the LA. Color-flow Doppler and pulsed techniques correlate well with angiographic methods of estimating the severity of mitral insufficiency. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), especially color mapping, is superior to transthoracic echocardiography in assessing the degree of mitral regurgitation. Although slight overestimation may occur, TEE also is useful in delineating the anatomy of the mitral valve and thus is useful for determining whether the mitral valve can be repaired or whether mitral valve replacement will be necessary.

Cardiac catheterization demonstrates elevated LA pressure (particularly the v wave). The diagnosis can be established by left ventriculography. Mitral insufficiency is indicated by the appearance of contrast material in the LA after LV injection through a retrograde aortic catheter.

Management Strategy

Medical therapy for asymptomatic patients with chronic mitral insufficiency is controversial. No long-term study supports any benefit of reducing preload or afterload by the use of vasodilators in these patients.

In patients who develop symptoms but with preserved LV function, surgery is the treatment option of choice. If atrial fibrillation develops, control of rate by digitalis, beta blockers, rate-lowering calcium channel blockers, and/or amiodarone will be necessary. Anticoagulation achieved by warfarin, maintaining an international normalized ratio between 2 and 3, also will be necessary to reduce embolic complications.

Surgery for mitral insufficiency is by mitral valve repair, mitral valve replacement with preservation of the subvalvular apparatus, or mitral valve replacement without preservation of the subvalvular apparatus. Each of the treatment options has its own advantages and disadvantages. Asymptomatic patients with severe mitral regurgitation should undergo surgery if deterioration of the LV function is present during serial follow-up or if the ejection fraction is 0.6 or less, or if the end-systolic diameter is 45 mm or greater. Other compelling causes for performing surgery in the asymptomatic patient with mitral insufficiency include the development of atrial fibrillation and/or the development of pulmonary hypertension (pulmonary artery systolic pressure 50 mm Hg at rest or 60 mm Hg during exercise).

RHEUMATIC MITRAL STENOSIS

Stenosis of the mitral valve usually is secondary to rheumatic carditis. Other causes include congenital MS, atrial myxoma, infective endocarditis with bulky vegetations, and mucopolysaccharidosis of the Hunter-Hurley phenotype. The combination of MS and secundum atrial septal defect frequently is referred to as Lutembacher syndrome, but the MS almost always is rheumatic, and the association is fortuitous.

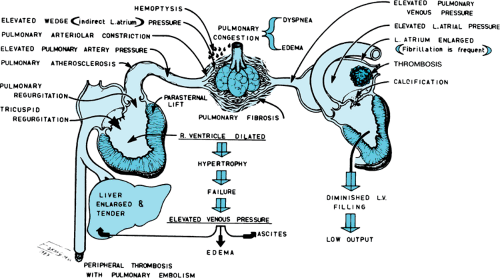

Rheumatic fever causes MS through fusion of the commissures, cusps, or chordae tendineae of the mitral valve apparatus (Fig. 286.4). Obstruction of flow across the narrowed mitral valve produces a diastolic gradient between the LA and LV. Serious circulatory disturbances, with consequent clinical symptoms, occur when the area of the mitral opening is less than 1 cm2. As narrowing proceeds, the LA pressure increases, as does the pressure in the pulmonary veins and capillaries, leading to lung congestion. Pulmonary arteriolar vasoconstriction occurs to protect the lungs against congestion, but the protection is at the expense of developing pulmonary hypertension, which produces right ventricle (RV) hypertrophy and possible RV failure (Fig. 286.5).

Clinical Manifestations

The symptoms of MS may appear insidiously within 3 to 4 years after the attack of acute rheumatic fever, or they may be delayed for as long as 50 years. The onset of symptoms sometimes is abrupt, and acute pulmonary edema, systemic embolism, or atrial fibrillation may be the initial manifestations. The symptoms depend on the state of the disease. No symptoms may be present in mild cases. If the lungs are congested, dyspnea, orthopnea, nocturnal dyspnea or pulmonary edema, recurrent chest infections, and hemoptysis will occur. As pulmonary hypertension develops, symptoms caused by lung congestion decrease, and low cardiac output symptoms (mainly exertional fatigue) begin to appear. Symptoms caused by systemic congestion appear if the RV fails.

In a patient with MS, the pulse usually is normal unless atrial fibrillation supervenes. The apical impulse is felt at the normal location as a “hurried, slapping” impulse. A characteristic diastolic or presystolic thrill ending in a palpable accentuated first sound can be detected over the apex. The first mitral sound is loud, short, and snappy. The accentuation of the first sound is caused by the open position of the cusps in the LV at the end of diastole as a result of the high LA pressure and the incomplete emptying of the LA. An opening snap occurs, which is a sharp, clicky sound separated from the second sound by the isovolumic relaxation phase. The snap is caused by the sudden opening

of the rigid mitral valve by the high LA pressure. The murmur characteristic of MS is a middiastolic or presystolic murmur. Developing pulmonary hypertension produces an accentuated pulmonary second sound.

of the rigid mitral valve by the high LA pressure. The murmur characteristic of MS is a middiastolic or presystolic murmur. Developing pulmonary hypertension produces an accentuated pulmonary second sound.

FIGURE 286.5. The diagram depicts the hemodynamic alterations and complications that occur because of mitral stenosis. LV, left ventricle. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree