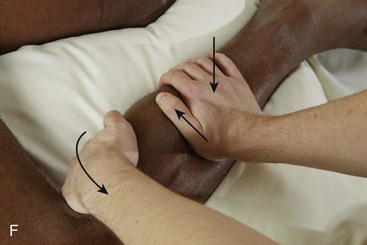

Chapter 11 After completing this chapter, the student will be able to perform the following: 1 Achieve determined outcomes by adjusting depth of pressure, drag, duration, frequency, direction, speed, and rhythm of all massage applications. 2 Apply all massage applications. 3 Apply joint movement methods. 1. Achieve determined outcomes by adjusting depth of pressure, drag, duration, frequency, direction, speed, and rhythm of all massage applications. All massage consists of a combination of the following qualities of touch: • Depth of pressure (compressive force), which can be light, moderate, deep, or variable. Depth of pressure is important. Most soft tissue areas of the body consist of three to five layers of tissue, including the skin; the superficial fascia; the superficial, middle, and deep layers of muscle; and the various fascial sheaths and connective tissue structures. Pressure must be delivered through each successive layer to reach deeper layers without damage and discomfort to more superficial tissues. The deeper the pressure, the broader the base of contact required with the surface of the body. It takes more pressure to address thick, dense tissue than delicate tissue. Depth of pressure is determined at the very beginning of the massage stroke. This means that every time a massage stroke is applied, compressive force is used before any other forces—first down, then out (Figure 11-1). FIGURE 11-1 Depth of pressure. A, Surface. B, Light. C, Medium. D, Deep. E, Identify depth of pressure first—DOWN—then add glide—OUT. F, When kneading, identify depth of pressure first—DOWN—then add tissue movement forward—OUT—then introduce torsion force. • Drag is the amount of pull (stretch) on the tissue (tensile force) (Figure 11-2). FIGURE 11-2 Drag. A, Drag is produced when the contact on the skin of the client is secure and minimal lubricant is used. B, Drag pulls or pushes tissues into bind. • Direction can move from the center of the body out (centrifugal), or in from the extremities toward the center of the body (centripetal). Direction can proceed from origin to insertion (or vice versa) of the muscle following the muscle fibers, transverse to the tissue fibers, or in circular motions (Figure 11-3). FIGURE 11-3 Direction. A, Example of direction toward the torso following muscle fiber direction. B, Example of direction is transverse and across the muscle fiber direction. • Speed of manipulations can be fast, slow, or variable (Figure 11-4). • Rhythm refers to the regularity of application of the technique. If the method is applied at regular intervals, it is considered even, or rhythmic. If the method is disjointed or irregular, it is considered uneven, or nonrhythmic. • Frequency is the rate at which the method repeats itself in a given time frame. In general, the massage practitioner repeats each method about 3 times before moving or switching to a different approach. The first application is assessment, second is treatment, and third is post-assessment. If the post-assessment indicates remaining dysfunction, then the frequency is increased to repeat the treatment/post-assessment several more times. • Duration is the length of time that the method lasts or that the manipulation stays in the same location. Typically, duration should not be longer than 30 to 60 seconds. Compressive forces occur when two structures are pressed together (Figure 11-5). Compressive force is a component of massage application and is described as depth of pressure. This kind of force may be sudden and strong, as with a direct blow (tapotement), or it may be slow and gradual, as with gliding strokes. The magnitude and duration of the force are important in determining the outcome of the application of compression. Some tissues are resilient to compressive forces, whereas others are more susceptible. Nerve tissue is an interesting example. Nerve tissue is capable of withstanding moderately strong compressive forces if they do not last long (such as a sudden blow to the back of your elbow that hits your “funny bone”). However, even slight force applied for a long time (as occurs with carpal tunnel syndrome) can cause severe nerve damage. The practitioner needs to consider this when determining the duration of a massage application using compression. Tension forces (also called tensile force) occur when two ends of a structure are pulled apart from one another (Figure 11-6). This is different from muscle tension. Muscular tension is created by excessive amounts of muscular contraction and not by strong levels of pulling force applied to the tissue. Muscles that are long from being pulled apart are affected by tensile force. Certain tissues, such as bone, are highly resistant to tensile forces. It would take an extreme amount of force to break or damage a bone by pulling its two ends apart. However, soft tissues are susceptible to tension injury. In fact, tensile stress injuries are the most common injuries to soft tissues. Examples of such injuries include muscle strains, ligament sprains, tendonitis, fascial pulling or tearing, and nerve traction injuries (i.e., sudden nerve stretching such as occurs in whiplash). Bending forces are a combination of compression and tension (Figure 11-7). One side of a structure is exposed to compressive forces, while the other side is exposed to tensile forces. Bending occurs during many massage applications. Pressure is applied to the tissue, or force is applied across the fiber or across the direction of the muscles, tendons or ligaments, and fascial sheaths. Bending forces rarely damage soft tissues; however, they are a common cause of bone fracture. Bending force is effective in increasing connective tissue pliability and affecting proprioceptors in the tendons and belly of the muscles. Shear is a sliding force (Figure 11-8). As a result, significant friction often is created between the structures that are sliding against each other. The massage method of friction uses shear force to generate physiologic change by increasing connective tissue pliability and creating therapeutic inflammation. An area of confusion in the massage profession involves consistent use of descriptive terminology. Any type of massage application can have multiple names. Definitions of massage-related terms were used for clarifying purposes during development of the Massage Therapy Body of Knowledge project (Box 11-1). This terminology has been used in this textbook.

Review of Massage Methods

Components of Massage Application

![]() Visit your Evolve website to watch these videos:

Visit your Evolve website to watch these videos:

Compression

Tension

Bending

Shear

The Methods

Review of Massage Methods