CHAPTER 12 Research related to clinical applications of manual therapy for musculoskeletal and systemic disorders from the osteopathic experience

Current status of manual therapy research for musculoskeletal disorders

As briefly discussed in Chapter 1, manual therapy has succeeded in obtaining recognition by scientific and governmental entities for clinical application in patients suffering from musculoskeletal pain, which is the most common reason for a person to seek primary medical care in the US (USBJD 2009). In addition to primary care and manual therapy practitioners, a number of medical specialties, including orthopedics, rehabilitation, neurology, and rheumatology, devote much of their clinical attention to musculoskeletal disorders. However, the research emanating from the non-osteopathic medical specialties has focused on surgical, exercise, and pharmacological interventions, and relatively little on manual therapy applications.

In the current era of emphasis on evidence-based practice, it is interesting to note in relation to musculoskeletal disorders that there is no evidence-based research supporting surgery for low back pain (Palmer & Patijn 2009), and that only 13% of all medical practice is considered beneficial, with another 23% considered likely to be beneficial (BMJ Clinical Evidence Centre 2009). Traditional practices taught and handed down through postdoctoral medical training still rely greatly on expert opinion and generally accepted standards of practice for credibility.

Based on the osteopathic concepts presented in Chapter 1, osteopathic research has reached the level of established benefit of OMT for chronic low back pain. Licciardone (Licciardone et al. 2005) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the randomized controlled clinical trials of OMT applied to patients with chronic low back pain. This analysis was favorable for benefit of OMT in these patients.

Based primarily on chiropractic research, practice guidelines published in 1994 (Bigos et al. 1994) accepted the clinical application of spinal manipulation in the care of low back pain if there were no other contraindications. Such contraindications included the presence of cancer or infection around the spine, or conditions such as cauda equina syndrome, which involve compromise of the L3–S2 nerve roots, rendering spinal manipulation too dangerous owing to the possibility that the condition could be exa-cerbated. A Cochrane Review (Assendelft et al. 2004) found that spinal manipulation was more effective in reducing pain and improving the ability to perform everyday activities than sham (fake) therapy and therapies already known to be unhelpful. However, it was no more or less effective than medication for pain, physical therapy, exercises, back school, or the care given by a general practitioner. Other systematic reviews give qualified conclusions: typical is that of Cherkin (Cherkin et al. 2003), who concluded that spinal manipulation has small clinical benefits that are equivalent to those of other commonly used therapies.

Subsequent to the reviews reported above, other clinical trials of manual therapy applied to patients with low back pain have been reported. Geisser et al. (2005) reported a single-blind (because the treatment provider knew whether they were administering real or sham manual therapy) randomized controlled clinical trial of manual therapy for low back pain with adjuvant exercise. In this trial the patients did not know whether they received real or sham therapy, and the data gatherer was also blind to the patient’s treatment. The researchers found that patients receiving manual therapy with specific exercise significant improvements in pain when controlling for pretreatment levels of pain. No significant changes in disability were observed, with the exception that the sham manual therapy-specific exercise group displayed a significant increase in disability over the 6 weeks of the study. Based on reports such as those reported above, the medical literature in primary care includes manual therapy in management plans for low back pain (Patel & Ogle 2000).

As set forth in the Preface, the focus of this book is the nature of the research on viscerosomatic interactions and related concepts that may pertain to the mechanisms of action for manual therapy. Our focus must, however, be seen in the context of the traditional and usual clinical application of manual therapy and related research, which is devoted mainly to conditions of the musculoskeletal system. The above brief review is intended to make the point that there is evidence-based research supportive of the benefit of manual therapy in certain musculoskeletal conditions, primarily low back pain. There is also an emerging body of research supportive of benefit for manual therapy in a variety of musculoskeletal conditions, based primarily on the structure–function relationship between anatomic structures and the function of nerve and vascular structures possibly affected by the dysfunctional anatomic structures. For further discussion of these and other studies supportive of the benefit of manual therapy, the reader is referred to Evidence-Based Manual Medicine (Seffinger & Hruby 2007).

Impact of manual therapy on systemic disorders and physiologic functions

As demonstrated by references to AT Still’s reported experience and Louisa Burns’ (1907) original formulation and research on viscerosomatic reflexes, the manual therapy professions have long reported impact of their manual applications for systemic disorders. This is still a controversial field of inquiry, with only a few systemic disorders and physiologic functions receiving more than one published research report. There have been a number of case reports that have served to support and maintain clinical application of OMT in these conditions during the past 100 years, and these are not reviewed here. It is acknowledged from the outset that there are relatively few large-scale studies, and no claims of ‘proof’ are made. However, the breadth and unique nature of topics and findings are potentially valuable from a heuristic perspective in so far as the development of future larger well-designed studies is concerned.

Pulmonary and immune system function

One of the important events in the establishment of the osteopathic medical profession in the public eye was the benefit of OMT in the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic. In the USA, 500 000 people died of the influenza in 1917–1918, and between 50 and 100 million more died worldwide. From survey data collected at the time, it appeared that patients treated osteopathically during 1917–1918 had a 0.25% mortality rate, compared to the national average of 6%, and 10% for pneumonia patients, and compared to 33–75% for the national average (Smith 1920).

In the past 10 years well-designed clinical trials have investigated the effects of rib raising and other OMT techniques on pulmonary disease, particularly pneumonia in the elderly. These studies are summarized in Table 12.1. After the experience derived from the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic, the OMT armamentarium for the treatment of pulmonary disease was increased to include lymphatic pump techniques (Miller 1923, 1927), which have now been studied extensively in both human and animal models. As described below, increased lymphatic flow is related to increases in immune system cell counts (Hodge et al. 2007), but it is important to distinguish between effleurage – a stroking of the skin which acts superficially to move fluids, including lymph – and the osteopathic lymphatic pump techniques, which involve manually guided forces over the ribs and abdominal area, or through leg motion generated from the feet with enough force to move lymph centrally. While the emphasis has been on techniques directed toward an impact on centrally situated structures, vertebral and paravertebral bone, nerve, muscular, and connective tissue, these techniques are often combined with lymphatic pump techniques directed at structures involved in lymph circulation, such as the respiratory diaphragm and chest muscles.

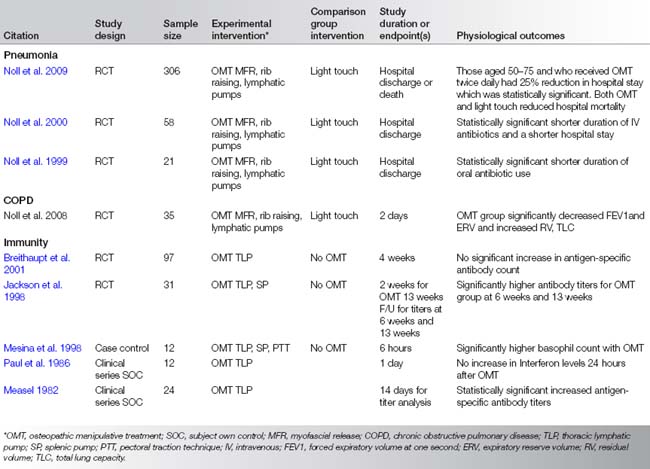

Table 12.1 Comparison-group studies investigating osteopathic manipulative treatment in pulmonary disease and immune system function (immunity)

Using an OMT protocol (Noll et al. 2008b) directed toward an impact on axial skeleton structures and lymphatic pump techniques, Noll conducted two preliminary studies (Noll et al. 1999, 2000) which found significant reductions in the use of intravenous antibiotics and duration of hospital stay in elderly pneumonia patients. Based on these studies, a multisite clinical trial using OMT on elderly patients hospitalized with pneumonia was carried out. At the time of writing of this chapter, the results of this clinical trial were in review for publication. However, some results were presented at the 2008 meeting of the Infectious Disease Society of America (Noll 2009) and confirm the preliminary study findings of reduced hospital stay associated with the OMT protocol.

Not all findings were positive, but even these negative studies have implications for understanding the optimal application of manual therapy, especially as related to mechanism of action. A COPD study which used the osteopathic lymphatic pump technique (Noll et al. 2008a) found evidence of worsened alveolar air trapping. The authors speculate that the ‘active’ component of the thoracic lymphatic pump technique was primarily responsible for the increase in residual volume because the activation portion of the technique promotes a sudden rush of air into the lungs. This air may not be fully exhaled in the context of airway resistance in COPD. If this is found to be the case, the authors recommend elimination of this OMT technique in cases of COPD. However, the authors also pointed out that this study did not deal with long-term effects, which could be quite different.

Five studies that used OMT on human subjects had outcome measures related to immune system function. Three showed immune system enhancement in the form of increased antigen-specific antibody titers (Measel 1982), increased basophil count (Mesina et al. 1998), and increased vaccine antibody titers (Jackson et al. 1998) following OMT. Authors of the other two studies, which showed no immune system enhancement (Breithaupt et al. 2001, Paul et al. 1986), speculated that time from OMT to laboratory testing and host response issues mitigated their findings. Nevertheless, with improved technology, research design, and sufficient funding, the likelihood that further clinical research would demonstrate benefit of OMT for immune system function appears promising. Similar results from the massage therapy literature (see Chapter 15) support this view, and together constitute an emerging consensus on the benefit of manual therapy for immune system function.

The lymph flow stimulation question was answered in a study on instrumented conscious, non-anesthetized dogs. Eight minutes of lymphatic pump technique adapted to dogs produced measurable increases in thoracic duct flow (Knott et al. 2005). Building on this research, Hodge et al. (2007) replicated the enhanced lymph flow finding and found that the lymphatic pump treatment (LPT) also significantly increased leukocyte count and flux. Leukocyte flux is the combination of lymph flow and leukocyte count, giving a more complete picture of the total impact on the body of the LPT, and provides a mechanism of action for the benefits seen in human clinical applications of such techniques. Research by Hodge (2009) indicates that the source of most of the leukocytes stimulated by the LPT is gastrointestinal-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT). These results are yet to be replicated in humans, but certainly suggest the likely mechanism of action for humans as well.

In summary, human and animal model investigations have provided some insight into the mechanism of action for manual therapy effects in pulmonary disease, which appear to be related, at least in part, to humoral factors in immune system enhancement (Licciardone 2010). According to research reported so far, there are no data to support any autonomic effects, though the idea of nervous system involvement is suggested by osteopathic concepts (see Chapter 1).

Pregnancy and reproductive system function

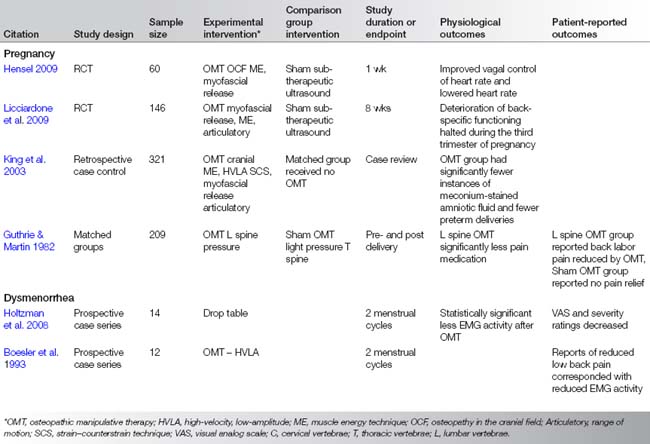

Another area where the application of OMT has received much attention is its impact during pregnancy and with reproductive system disorders. Table 12.2 summarizes the studies cited in this section. Two studies (Guthrie & Martin 1982, Licciardone et al. 2010) showed significant reduction of low back pain during pregnancy when OMT was provided. One investigation (King et al. 2003) found that pregnant women who received OMT had significantly fewer preterm deliveries and instances of meconium-stained amniotic fluid. A physiological study on women in the third trimester showed improved vagal control of heart rate after just one OMT treatment (Hensel 2009). The Hensel study continues and will also assess birth outcomes.

Table 12.2 Comparison-group studies investigating osteopathic manipulative treatment for pregnancy and reproductive system conditions in women

OMT applied during pregnancy is another application which may have very significant healthcare benefits and cost savings. The cost to society of preterm deliveries alone is in the billions (King et al. 2003), and if OMT reduces this cost then further study should be a high priority. Spinal manipulation in pregnancy and related conditions has been systematically reviewed (Khorsan et al. 2009) and described as an ‘emergent’ field of study.

The two studies (Boesler et al. 1993, Holtzman et al. 2008) investigating the impact of OMT on dysmenorrhea were positive for reported pain reduction, and one (Boesler et al. 1993) even showed reduced EMG activity after OMT. Taken together with the chiropractic studies on the treatment of dysmenorrhea (Chapter 14), a case can be made for greater clinical application of manual therapy for dysmenorrhea, as long as there are no contraindications for a particular patient.

Indeed, the results of OMT applied in pregnancy, as well as OMT and chiropractic applied in the treatment of dysmenorrhea, may be just the beginning of broader applications in women’s health. The mechanism of action in pregnancy and dysmenorrhea appears to be improved musculoskeletal alignment and balance, as suggested by Hensel (2009). If this is further delineated by her ongoing research, then overall female reproductive system function improvement may be a realistic expectation for manual therapy, especially OMT. This author’s clinical experience with improved menstrual regularity and reduced dysmenorrhea also supports this possible outcome. The likely mechanism of action for OMT in pregnancy and reproductive system functions is impact innervation of these organs, with some possible lymphatic flow enhancement.

OMT in the hospital and surgical setting

Osteopathic physicians who do surgery and who care for hospitalized patients have also contributed to the research literature on the effects of OMT. Table 12.3 summarizes the studies described in this section. In the USA, osteopathic physicians have the ‘full scope of medical practice’ licence. Many osteopathic physicians are surgeons, and this has facilitated research on the application of OMT to hospitalized patients. The OMT protocols utilized in these studies were directed toward axial skeletal areas where somatic dysfunction could affect autonomic nervous system function, as well as peripheral areas that could affect vascular flow. Such areas were the occipito- atlanto and sacral areas possibly influencing functions related to the parasympathetic nervous system (i.e., gastrointestinal tract, heart, lung, pelvic organs) and T1–L5 segments targeting somatic dysfunctions and function related to the sympathetic nervous system.

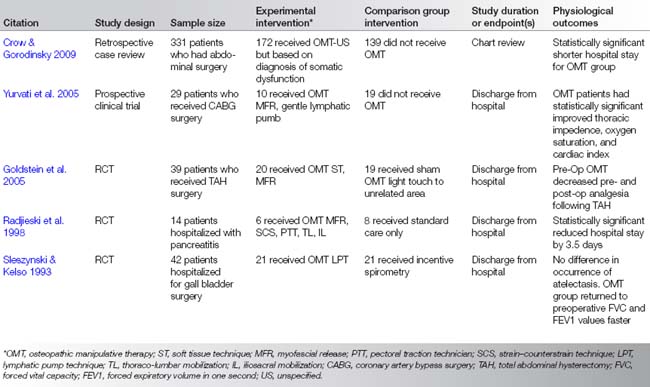

Table 12.3 Comparison-group studies investigating osteopathic manipulative treatment as adjunctive treatment patients requiring hospitalization or surgical case management

One study on women who had had a hysterectomy found that preoperative OMT significantly reduced the need for postoperative analgesia (Goldstein et al. 2005). Unfortunately, due to insufficient hospital record keeping it was not possible to evaluate the subjective impression that these same patients also recovered faster.

In a dramatic study on outcomes in coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG), investigators found that the application of postoperative OMT significantly improved drainage from the operative site (Yurvati et al. 2005). Postoperative oxygen saturation and cardiac efficiency were also significantly improved in the patients who received OMT compared to those who did not. The OMT protocol utilized cervical spine and upper thoracic techniques to reduce the strains caused by prolonged anesthesia and open chest surgery.

In a substantial chart review study, patients who had had abdominal surgery and also had the diagnosis of postoperative ileus were examined (Crow & Gorodinsky 2009). In this particular hospital, OMT service was available to inpatients. Those who received OMT postoperatively had significantly shorter hospital stays than those patients who did not. This study supported the clinical experience that postoperative OMT improved bowel function and reduced the duration of ileus symptoms.

Another postoperative complication studied was atelectasis (Sleszynski & Kelso 1993). The results of the application of OMT did not reduce the occurrence of atelectasis, but the OMT was correlated with a faster return to preoperative respiratory function. Patients hospitalized with pancreatitis were also studied (Radjieski et al. 1998): those who received OMT had significantly shorter hospital stays.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree