Repair of Acute and Chronic Knee Medial Collateral Ligament Injuries

Adam V. Metzler

Darren L. Johnson

DEFINITION

A medial collateral ligament (MCL) injury usually is the result of a valgus stress on the knee.

Forced external rotation injuries with a valgus component also have been described as a mechanism that can disrupt the MCL.

Although the direct valgus force is more likely to injure the superficial MCL, external rotation and valgus stress often causes additional injuries to the deep MCL, the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), the posteromedial corner, or the posterior oblique ligament (POL).

The most common combined injury is an ACL and MCL injury followed by meniscus injuries.

ANATOMY

Both static and dynamic forces are responsible for resisting valgus forces at the knee. The major static stabilizers of the medial knee include the POL, superficial MCL, and deep MCL. The major dynamic forces that resist valgus load include the medial head of the gastrocnemius, vastus medialis, pes anserinus, and semimembranosus.

The medial side of the knee can be divided into three layers: superficial (I), intermediate (II), and deep (III).

Layer I: The crural fascia invests the quadriceps fascia and the sartorius proximally and the pes anserinus and tibial periosteum distally.

Layer II: The superficial MCL and the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) lies between layers II and III.

Layer III: the deep MCL (ie, the meniscotibial and meniscofemoral ligaments) and the posteromedial corner (ie, semimembranosus and POL)

The superficial MCL originates from the medial femoral epicondyle. It inserts approximately 4 to 6 cm distal to the medial joint line and can be divided into an anterior and a posterior portion. The anterior portion tightens in flexion; the posterior portion tightens in extension.

The deep MCL tightens in knee flexion and is lax in full knee extension.

The posteromedial corner provides rotational stability to the medial side of the knee. Injuries to these structures cause anteromedial rotatory instability.

The semimembranosus has five main attachments to the posterior capsule of the knee:

Pars reflexa, attaching directly to the proximal medial tibia

Direct arm, attaching to the posteromedial tibia

Insertion to the proximal medial capsule

Attachment to the POL

Attachment to the popliteus aponeurosis

PATHOGENESIS

The typical mechanism for an MCL injury is a valgus stress acting on the knee joint with the foot planted. This mechanism often leads to a disruption of the deep and superficial MCL.

If an external rotational component is added, a disruption of additional restraints such as the ACL and the posteromedial corner is likely. In particular, an injury to the POL indicates a significant capsular injury that leads to a higher grade of medial and rotatory instability.4

MCL injuries can be partial or complete. A complete MCL injury involves disruption of the superficial and deep MCL and usually results initially in inability to ambulate.

MCL injuries can be on either the femoral or tibial side. It is important for the treatment algorithm to differentiate whether the tear involves the femoral origin of the MCL or the tibial insertion.

NATURAL HISTORY

Acute isolated MCL injuries usually are treated nonoperatively with protective weight bearing and bracing for 2 to 6 weeks.

In particular, partial tears of the MCL (grade 1 or 2) heal well with conservative treatment.

Complete MCL injuries (grade 3 injuries) initially can be treated conservatively if they are femoral-based ligament ruptures.4

A complete tibial-sided MCL avulsion with POL extension is less likely to tighten up with nonoperative management and often requires repair or reconstruction. Rarely seen as an isolated injury.

Grade 3 MCL injuries in combination with other ligament injuries of the knee may require acute surgical repair in case of a complete tibial avulsion with POL extension.7

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A description of the mechanism of injury (eg, valgus mechanism, valgus rotation mechanism) must be elicited.

The examination includes inspection for peripheral hematoma along the medial side of the knee and palpation of hamstrings, joint line (meniscal injury), and the femoral origin and tibial insertion of the MCL for stability testing.

Acute evaluation of an MCL is ideal, if possible, before muscle spasms occur.

A thorough evaluation of the neurovascular status of the extremity is imperative to avoid missing a limb-threatening situation.

Valgus stress at 0 and 30 degrees: grade 1 (0- to 4-mm opening) and grade 2 (5- to 9-mm opening) injuries usually can be treated nonoperatively; grade 3 (10- to 15-mm opening)

injuries are associated with other ligament tears (ie, ACL, POL) in over 75% of cases.

Slocum modified anterior drawer test: Disruption of the deep MCL allows the meniscus to move freely and allows the medial tibial plateau to rotate anteriorly, leading to an increased prominence of the medial tibial condyle.

Anterior drawer test in external rotation: Disruption of the MCL alone should not lead to an increased anteromedial translation. An increased anteromedial translation indicates an anteromedial rotatory instability that involves an injury of the posteromedial capsule (eg, POL, semimembranosus attachments as well as deep MCL).

A thorough examination of the knee should always include the following assessments:

Meniscus: tenderness directly at the joint line is a sensitive sign for a meniscus injury. The McMurray test or a flexion-rotation-compression maneuver may accentuate medial joint line pain, suggesting a medial meniscus tear. (This test may not be helpful in an acute setting.)

ACL: An immediate (within 24 hours) intra-articular effusion after the injury indicates a high likelihood of ACL injury. Positive Lachman test (acute) and pivot shift test (chronic) indicate an associated ACL tear. In the acute or subacute setting, these tests may be difficult to perform. Instrumented laxity testing (KT-1000) may be helpful in these situations. An increased valgus laxity in full extension almost always indicates one or both of the cruciate ligaments are injured. Some surgeons use this as an indication for subacute/acute MCL repair.

Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL): A positive posterior drawer test indicates a PCL injury. The end point is important to assess the grade of the PCL injury.

Patella: The apprehension sign and localized tenderness on the lateral or medial aspect of the patella or the lateral trochlea indicates a possible patella dislocation, which can go hand-in-hand with an intra-articular effusion. Tenderness at the medial femoral epicondyle also can be caused by an avulsion of the MPFL.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographs help to assess the bony integrity of the knee joint. They may show indirect signs of ligament injury (eg, Segond fracture), but they usually are not helpful for the diagnosis of an acute MCL injury.

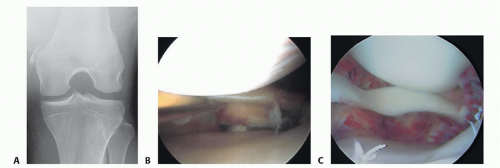

In the case of chronic MCL instability, a Pellegrini-Stieda lesion (bony spur originating at the femoral origin of the MCL, usually visualized on the flexion weightbearing posteroanterior radiograph) may be present (FIG 1A).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with or without contrast is helpful to identify MCL damage.

Edema or MCL disruption can be visualized.

The location and extent of the disruption (femoral vs. tibial) can be determined.

The amount of bone bruising can be assessed, and associated pathology (eg, meniscal tears, ACL tears, posteromedial corner injuries) can be visualized.

Isolated grades 1 and 2 MCL injuries can be diagnosed clinically; and generally, an MRI is not indicated unless the patient has an intra-articular effusion or signs of other ligament injury.

Arthroscopic examination is a formidable tool to assess the true nature of the MCL injury.

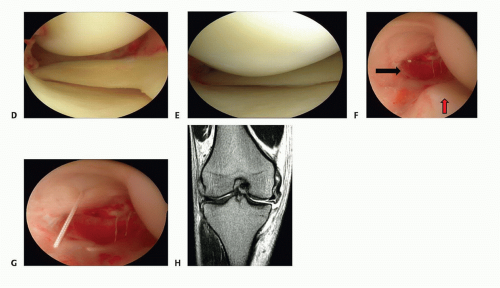

An ipsilateral “drive-through” sign (ie, opening of the medial compartment of more than 10 mm, allowing for complete insertion of the arthroscope into the medial compartment [FIG 1B]) should arouse suspicion for a significant MCL injury that may require repair or reconstruction. If one can see easily the entire medial meniscus posterior horn, then you have significant medial opening. If the meniscus follows the femur, you have a tibial-sided lesion; if the meniscus stays with the tibia and the gap is above the meniscus, you have a femoralsided lesion.

The location of the acute or chronic injury—femoral or tibial—also can be evaluated. Separate injuries of the POL also can be visualized (FIG 1C-F).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Medial meniscus tear

ACL tear

Posteromedial corner injury

Patella dislocation

Pes-anserine bursitis

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Grades 1 and 2 Medial Collateral Ligament Sprains

Rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE) for 24 hours or until swelling is controlled.

Once swelling is controlled, partial weight bearing, range-of-motion (ROM) exercises, and electrical stimulation can be started. A simple hinged brace is applied.

Full weight bearing can be allowed once ROM over 90 degrees of flexion as well as motor control of the thigh musculature has been demonstrated.3,6

Once full ROM and 80% strength of the opposite side have been achieved, closed kinetic chain exercises, jogging, and treadmill exercise may begin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree