Release of the A1 Pulley to Correct Pediatric Trigger Thumb

Roger Cornwall

DEFINITION

Pediatric trigger thumb is a condition in which tightness of the first annular (A1) pulley of the thumb and an enlargement or nodule of the flexor pollicis longus tendon interact to prevent normal thumb interphalangeal joint motion.

This condition appears distinct from pediatric trigger fingers and from adult trigger digits, although similarities in pathoanatomy and presentation have earned it its name.

ANATOMY

The flexor pollicis longus tendon courses through a flexor sheath in the thumb composed of a series of pulleys that prevent bowstringing of the tendon during thumb flexion.

The most proximal pulley is termed the A1 pulley, given its transverse annular nature. Division of this pulley does not cause bowstringing of the tendon during thumb flexion. The next pulley is the oblique pulley, although some authors have described an intervening distinct second annular pulley analogous to the A2 pulley in the fingers.2 These pulleys are important constraints against bowstringing.

The digital nerves to the thumb are in proximity to the flexor pollicis longus tendon sheath. The radial digital nerve obliquely crosses the tendon sheath just proximal to the A1 pulley, and the ulnar digital nerve runs parallel to the tendon immediately alongside the A1 pulley. Injury to these structures is possible during surgical release of the A1 pulley, so precise knowledge of the anatomy is important.

PATHOGENESIS

The pathogenesis of pediatric trigger thumb is unknown, although recent evidence implicates benign proliferation of myofibroblasts during growth.13

In adults, the pathogenesis of trigger digits has a predominantly inflammatory nature. However, in pediatric trigger thumb, biopsies have been unable to detect signs of inflammation by gross morphology or light or electron microscopy.3

A genetic predisposition has been considered, especially in cases of bilateral trigger thumb, but a genetic cause for the condition is not established.28

Traumatic etiologies have been proposed but with no clear data to support this theory.

NATURAL HISTORY

The natural history of pediatric trigger thumb has been a focus of recent attention. The earliest reports of the condition described spontaneous resolution as rare, but newer reports have described spontaneous improvement rates of 24% to 63%.1, 5, 20

A recent study1 regarding the natural history of pediatric trigger thumb reported a 63% resolution rate, although the definition of resolution was improvement in passive interphalangeal joint extension to neutral, not to the normal hyperextension. Furthermore, the average time to reach this improvement was 48 months from diagnosis.

Therefore, when considering the use of observation to treat a pediatric trigger thumb, the clinician should inform the parents that the thumb motion may improve but not return to normal and that such improvement will take an average of 4 years.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Children typically present from late infancy through 5 years of age with painless loss of motion at the interphalangeal joint. The “triggering” phenomenon that so commonly occurs in adults is rare in children.

Parents will usually be unable to determine how long the condition has been present. Some parents will describe a preceding traumatic injury to the thumb, although such an injury may simply call the parents’ attention to the thumb closely enough to notice a preexisting trigger thumb.

Functional impairment and pain are unusual complaints, except in the case of active triggering.

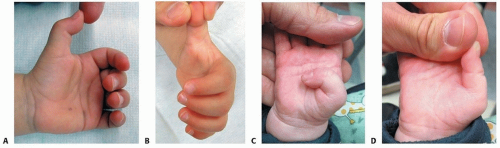

The typical physical examination finding is a flexion contracture of the thumb interphalangeal joint, as the nodule in the flexor pollicis longus tendon typically lies proximal to the A1 pulley, preventing distal excursion of the tendon and extension of the interphalangeal joint (FIG 1A).

In a few cases, the nodule lies distal to the A1 pulley and the thumb rests in an extended position with the child unable to actively flex the interphalangeal joint. In this case, the passive flexion of the interphalangeal joint is normal, but interphalangeal joint flexion will not occur by tenodesis with wrist extension.

In even fewer cases, the child will be able to actively “trigger” the thumb with active flexion and passive extension.

Regardless of the position of the thumb interphalangeal joint, a nodule is easily palpable (and even visible) in the flexor pollicis longus tendon in the region of the palmar digital crease (FIG 1B). The nodule can be felt to move proximally and distally with even the few available degrees of movement of the interphalangeal joint.

In long-standing cases of fixed flexion deformity, thumb metacarpophalangeal joint hyperextension laxity is common.

In other cases, a coronal plane deformity resembling clinodactyly may be present, although a causative relationship has yet to be established.

Because of the possibility of bilateral involvement, both thumbs should be examined.

An upper limb neurologic examination should be performed, including an assessment of tone in the intrinsic muscles of the hand because the thumb-in-palm deformity of cerebral palsy can be confused with trigger thumb.

Pediatric trigger thumb should not be confused with congenital clasped thumb, in which the metacarpophalangeal joint is fixed in a flexed position, with normal interphalangeal joint motion (FIG 1C,D).

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Radiographs are unnecessary in the clinically obvious case; if obtained, they only confirm the resting position of the thumb interphalangeal joint.

Radiographs may be misinterpreted as demonstrating a dorsal dislocation of the metacarpophalangeal joint due to its hyperextended posture, leading to attempts to “reduce” the dislocation. Often, these misguided attempts to reduce the dislocation involve traction on the thumb, which may pull the nodule through the pulley by extending the interphalangeal joint, satisfying the practitioner and parent that the problem has been solved. The flexed posture usually returns by the following morning, leading to a diagnosis of recurrent dislocation. Familiarity with the diagnosis of trigger thumb and its radiographic and clinical findings can prevent this cycle of intervention and anxiety.

If the examination reveals signs of trauma (eg, swelling, ecchymosis), radiographs should be considered to rule out underlying skeletal injury.

Advanced imaging is unnecessary.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Congenital clasped thumb

Thumb-in-palm deformity (cerebral palsy)

Arthrogryposis

Thumb hypoplasia

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative management of pediatric trigger thumb has been described, including simple observation,1 daily stretching by parents,30 splinting,16, 21 and casting,4 but it is unclear if any nonoperative treatment alters the natural history.

A recent systematic review7 summarized the results of conservative treatment of pediatric trigger thumbs as follows. Splinting was reported in 138 thumbs in 4 studies15, 16, 21, 26 with an overall success rate of 67% over 2.9 to 30 months, although the splinting was complicated by poor compliance and splint complications such as contact dermatitis. Many patients treated with splinting dropped out of the treatment to proceed with surgery. Passive stretching of the thumb was reported in 108 thumbs in 3 series,8, 12, 30 with an overall success rate of 55% after 21 to 24 months of daily exercising. In addition, the success was even lower for thumbs locked in flexion. Therefore, the author discourages the use of nonoperative treatment, as it does not appear to alter the natural history despite long, arduous treatment regimens.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree