10 Relaxation massage

Stress

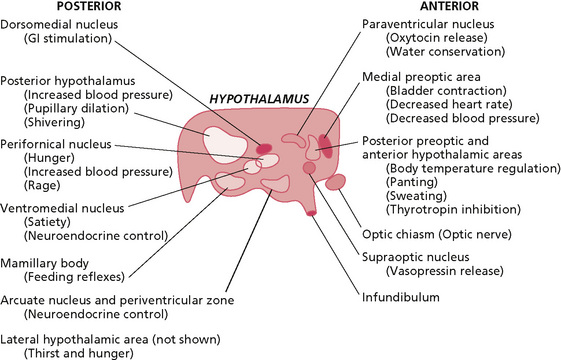

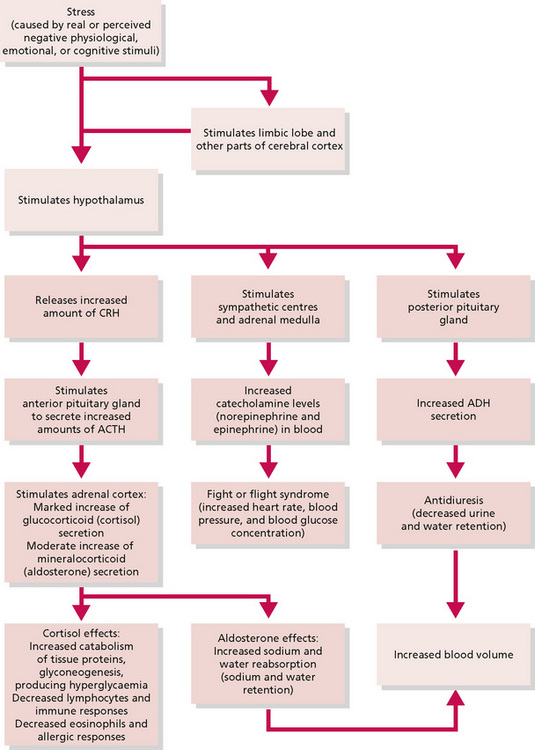

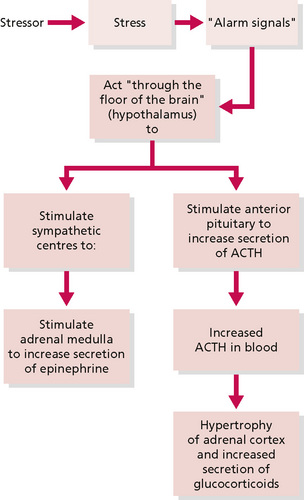

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) was discussed in Chapter 3 in connection with the reflex effects of massage. That discussion is extended here, applied specifically to stress and autonomic arousal. The relevant function of the ANS to relaxation massage is that when an individual experiences severe fear or pain, or has a strong emotional reaction, the hypothalamus is stimulated to transmit impulses to the spinal cord which cause a sympathetic discharge, resulting in the alarm response, or general adaptation syndrome (Seyle 1982) (Fig. 10.1). This is the protective mechanism which prepares an animal or human for ‘flight or fight’, to ensure that, whichever of these actions is chosen, the animal is physiologically prepared for vigorous activity. The changes include an increase in blood levels of glucose, cortisol, adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine), and an increase in blood pressure, blood flow to skeletal muscles, muscle tone and heart rate—the sympathetic stress response (Figs. 10.2 and 10.3).

Figure 10.1 • • Control centres of the hypothalamus.

Reprinted from Textbook of Medical Physiology 8e, Guyton (1991) with permission from Elsevier.

Figure 10.2 • • Current concepts of the stress syndrome.

Reprinted from Anatomy and Physiology 6e, Thibodeau & Patton (2007) with permission from Elsevier.

Figure 10.3 • • Seyle’s hypothesis about activation of the stress mechanism.

Reprinted from Anatomy and Physiology 6e, Thibodeau & Patton (2007) with permission from Elsevier.

In Chapter 3 the concept of a stressor was briefly examined in relation to various types of touch and other stimulation via the sense organs. A stressor acts to arouse the sympathetic branch of the ANS; massage is frequently used to achieve the opposite effect, the aim being to provoke a decrease of activity in the sympathetic branch and an increase of activity in the parasympathetic branch of the ANS, thus returning the body to a normal balance.

Arousal is the result of an individual’s personal response to any stimulus perceived as a threat. Clinical stress may occur if the arousal persists and the individual develops feelings of being unable to cope; thus, stress can be viewed as a form of chronic arousal. Prolonged stress may result in raised levels of cortisol, which can have further harmful effects, such as decreased immunity and hypertension. Unremitting stress is undesirable for the human organism. To maintain health there must be a reversal of the arousal and a return to a normal baseline state of homoeostasis (Table 10.1).

Table 10.1 Stress-related diseases and conditions

| Target organ or system | Disease or condition |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular system | Coronary artery disease |

| Hypertension | |

| Stroke | |

| Disturbances of heart rhythm | |

| Muscles | Tension headaches |

| Muscle contraction backache | |

| Connective tissues | Rheumatoid arthritis (autoimmune disease) |

| Related inflammatory diseases of connective tissue | |

| Pulmonary system | Asthma (hypersensitivity reaction) |

| Hay fever (hypersensitivity reaction) | |

| Immune system | Immunosuppression or immune deficiency |

| Autoimmune diseases | |

| Gastrointestinal system | Ulcer |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | |

| Diarrhoea | |

| Nausea and vomitting | |

| Ulcerative colitis | |

| Genitourinary system | Diuresis |

| Impotence (erectile dysfunction) | |

| Frigidity | |

| Skin | Eczema |

| Neurodermatitis | |

| Acne | |

| Endocrine system | Diabetes mellitus |

| Amenorrhea | |

| Central nervous system | Fatigue and lethargy |

| Type A behaviour | |

| Overeating | |

| Depression | |

| Insomnia |

From Anatomy and Physiology 6e, Thibodeau & Patton (2007), Elsevier.