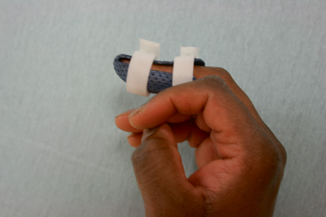

Fig. 11.1

Wrap technique to produce a rounded residual tip

Fig. 11.2

Wrap technique to produce a rounded residual tip

Scar massage is an adjunctive intervention that is begun promptly upon wound closure. [5] It is performed not only on the frank scar but also on the surrounding tissue when it feels dense, brawny, or hard. Firm pressure is applied to the area followed by one of the following: cross-friction, longitudinal, or circular movements. The clinician and patient should not move their fingers across the skin, but rather, should apply pressure into the deeper tissues changing finger position periodically to cover the entire effected area. The techniques employed in myofascial release provide a three-dimensional approach including applying pressure to the scar tissue through the transverse, sagittal, and coronal planes. Finger pressure is applied straight down into the affected area until resistance is met. Then a longitudinal, or sideways, pressure is applied to the tissue in the direction of scar or tissue resistance. The technique is completed by the third component of either a clockwise or counterclockwise pressure in the direction of resistance while maintaining the previous two directions of pressure. At this point, the scar tissue has been placed on tension in all three planes providing maximum therapeutic deformation forces. Pressure is held at this end point until tissue release is noted after which pressure is slightly increased to take up the slack from release. There are no published studies on the effectiveness of scar massage, but it is this author’s experience that tissue is noted to soften and lengthen when these techniques are employed.

Ultrasound may be used as an adjunct modality for the benefit of increasing range of motion and tissue extensibility. It is considered a superficial heating agent, and the literature demonstrates that the 3-MHz sound head may heat tissues to a depth of 2 cm. The literature does not, however, support the effectiveness of the use of ultrasound. Support for this modality is anecdotal. This author has found it effective in the majority of patients with recalcitrant scar tissue particularly when the scar crosses a joint. Putting the tissue on a stretch by passively moving the joint involved increased effectiveness. As with all modalities, it is important to be fully aware of all precautions and contraindications related to ultrasound use.

Distal Phalanx Fractures

Distal phalanx (P3) fractures are the most common fractures in the hand and are, typically, the least difficult to manage due to the relative simplicity of the soft tissue structures about the fingertip [31]. These fractures can be open or closed, may involve tendons , and be part or all of the structures of the nail. When establishing a treatment plan, it is important to consider the type of fracture, any surgical intervention performed, soft tissue structures involved, and fracture stability.

Tuft fractures, the most common P3 fractures, are often the result of crush injuries and usually require no surgical intervention. The hand surgeon may allow active range of motion during the first week with immobilization between exercise sessions. More often, immobilization of the DIP for 2–3 weeks is recommended [29]. A volar or clamshell orthosis with the DIP in neutral extension and the proximal-interphalangeal (PIP) free is recommended. There is no concern for possible development of a swan neck deformity with tuft fractures as the extensor tendon inserts proximal to this fracture sight. Three weeks post injury, the orthosis is discontinued and range of motion is begun. Periodic use of the orthosis during heavier tasks may be useful in preventing discomfort. Progression of therapy is based largely on patient tolerance as crush injuries to the fingertip often result in significant pain. In this author’s experience, tuft fractures generally do not require prolonged rehabilitation . Occasionally, the recalcitrant finger will require more aggressive treatment including prolonged stretching via static progressive or dynamic orthosis use to achieve maximal gains (Fig. 11.3). Rarely is a formalized strengthening program warranted. Often the sterile matrix is compromised with tuft fractures due to the congruous nature of the periosteum and the sterile matrix. After surgical repair of the sterile matrix, the surgeon will either reuse the nail plate or suture sterile foil in place for protection. It generally takes two full nail growth cycles to determine the final outcome of the nail. Preservation of the nail is preferred as it gives proprioceptive input to the pulp during manipulation and gripping activities. If the surgeon has not applied the nail or foil over the repaired matrix, pressure must be applied to the nail bed. This can be done by fabricating a dorsal orthosis fabricated from 1/16” thermoplastic material. The orthosis can be applied over a piece of gauze and held in place with self-adhering tape. It should be removed only for exercise and hygiene purposes. The pressure from the orthosis on the healing nail bed helps to facilitate a smoother end result .

Fig. 11.3

Static progressive orthosis

Both longitudinal and transverse fractures of the distal phalanx have been described, and, are frequently the result of crush injuries [29]. These fractures can be open or closed, involve the perionychium to varying degrees, and may be intra- or extra-articular. Simple, well aligned, closed fractures are typically treated with immobilization for 2–4 weeks based on healing progress and residual pain and swelling. When the orthosis is removed, active range of motion is initiated in the clinic, often two to three times a week, and at home five to six times daily. A desensitization program may need to be initiated at this point as, due to the high density of sensory receptors in the fingertip, hypersensitivity after crush injury is common. This author typically initiates passive range of motion at weeks 5–6 post injury or repair followed by strengthening and work simulation at weeks 7–8. Good communication with the referring physician is essential in determining the time line for rehabilitation based on fracture healing .

Some fractures require pinning to achieve proper alignment and future stability. Typically, a K-wire is used for internal fixation and is left in place for 4–6 weeks [1, 29]. If the DIP is not immobilized, the hand surgeon may allow gentle DIP active range of motion while the pin is in place with immobilization at all other times. If the pin protrudes from the skin, the orthosis should be fabricated to protect the pin from being inadvertently bumped during daily activities. Instruction in pin care is essential to prevent pin-site infection and possible osteomyelitis. Daily cleaning with a cotton swab and a mixture of 50/50 saline and hydrogen peroxide is recommended. The patient is instructed to keep the pin site dry at all other times. Once the pin is pulled, it is important to progress range of motion exercises with an eye toward possible attenuation . Over stretching of the relatively thin terminal extensor tendon can occur after prolonged immobilization, swelling, and scar formation from the initial injury and corrective surgery. If a lag is noted, daytime orthosis use with removal for active range-of-motion exercises, and night time immobilization are recommended. Exercises should be focused on full digit extension as well as flexion. Weaning from the orthosis may be initiated as DIP extension improves. Nighttime orthosis use may continue for several weeks. Passive range-of-motion exercises are initiated 1–2 weeks after pin pulling, dependent on fracture healing and status of DIP extension. These injuries may also require static progressive or dynamic orthoses to increase DIP joint flexion secondary to adaptive shortening of the oblique retinacular ligaments as well as other soft tissue about the joint (Fig. 11.3). As mentioned previously, careful monitoring for signs of attenuation is prudent. Strengthening and work simulation activities are initiated 8 weeks after surgery .

Seymour fractures are distal phalanx fractures that occur in children at the trans-epiphyseal plate. The terminal extensor tendon remains intact; however, the pull of the flexor digitorum profundus on the bone distal to the fracture sight causes the injury to present like a mallet injury. Often there is concomitant nail bed injury . Current literature supports fixation with a K-wire due to the severity of the fracture and potential noncompliance of children with orthosis use. Postoperative orthosis use to support the joint and protect the pin is recommended. Typically, formal therapy is not required.

Mallet Finger

Mallet finger injury is a disruption of the terminal extensor tendon that results in an inability to actively extend the DIP joint . Injury is generally caused by axial loading to an extended digit and may occur during sports, work, and household activities [23]. Mallet finger injuries occur in nearly 10 per 100,000 individuals [3] with a greater incidence in men than in women and they more often occur in the dominant hand. The digit most frequently affected is the long finger followed by the ring, index, small, and thumb, although mallet type injury of the thumb is rare [12]. The result of an untreated mallet finger may include the development of chronic DIP flexion with possible joint contracture, cold intolerance, osteoarthritis, chronic joint pain, and swan neck deformity resulting from the collapse of the extensor system from over pull of the central slip. Several classifications systems have been developed in order to describe the relative severity of the injury, including soft tissue and bony involvement [3]. Doyle’s classification describes four subsets of injury ranging from closed to greater than 50 % involvement of the articular surface [3]. Wehbe and Schneider’s classification describes three subsets of injury ranging from stable soft tissue injuries without DIP subluxation to unstable with bony involvement greater than two thirds of the articular surface .

There is controversy over whether to treat mallet finger injuries conservatively or surgically; however, it is generally accepted that conservative treatment is most appropriate when there is no bony involvement or when bony involvement does not exceed one third of the articular surface [1, 3, 16]. Furthermore, some studies suggest that, due to the distal phalanx’s superior ability to form bony callus, bony involvement with greater than two thirds articular surface involvement can be successfully treated conservatively with immobilization [1]. In fact, some prefer conservative treatment even with significant bony involvement due to the possible complications of surgery including pin-site infection and osteomyelitis . The financial cost of surgery can also be a concern. Regardless, as current literature confirms, patient compliance is necessary in order to achieve a successful outcome .

A number of studies have been conducted comparing casting and orthoses use for conservative treatment of mallet finger. Tocco [12] conducted a prospective randomized comparison of 57 closed mallet finger injuries that were treated conservatively with either the Quickcast® finishing tape or custom-made “lever type” thermoplastic orthoses (Fig. 11.4). All participants had either tendonous involvement alone or less than one-third articular surface involvement. Participants were immobilized at all times for 6–8 weeks, followed by 2 weeks of intermittent immobilization and 2 additional weeks of nighttime immobilization. Tocco concluded that DIP joint extension was greater in the continuous immobilization group that was casted than in the thermoplastic orthosis group . There were also a higher number of failures in the group that used an orthosis. However, there was no difference in pain or discomfort between the two groups [23, 30]. A single blind, prospective, randomized controlled trial was conducted comparing Stack® (Fig. 11.5), dorsal aluminum, and custom thermoplastic orthoses in 64 participants with terminal tendon involvement only or a small bony avulsion without DIP joint subluxation. [23] This study concluded that there was no significant difference in extensor lag no matter the form of immobilization. However, there were fewer complications with skin irritation and maceration with the use of the custom thermoplastic orthosis .

Fig. 11.4

Lever-type thermoplastic orthosis

Fig. 11.5

Stack (registered) splint

In keeping with the basic principles of hand therapy, the clinician must always be mindful of potential complications that may occur with orthosis and cast use. The epidermis may be compromised by maceration, pressure points, skin ulceration, ischemia, and skin necrosis. Ineffective protection of injured structures is also primary concern. Patient education and compliance are of paramount importance when conservative treatment is employed. A Cochran review in 2004 found that patient compliance is the most important factor when treating mallet finger injuries with orthosis immobilization [2]. The patient must have a clear understanding that fingertip immobilization in extension must be maintained for 6–8 weeks. If at any point during that time the DIP joint is allowed to flex, the timeframe for repair and immobilization essentially begins again . The DIP is positioned in slight hyperextension. Blanching should be avoided as it is an indicator of ischemia . The PIP joint is not immobilized. [28] However, if a swan neck deformity is noted, the PIP joint is positioned to prevent extension beyond 30° to lessen the pull of the lateral bands on the DIP joint. [13] Immobilization is continued for a period of 6–8 weeks. The orthosis is removed minimally. Once daily for hygiene purposes is recommended. The patient must maintain full DIP joint extension during orthosis removal. This author recommends practicing daily hygiene techniques in the clinic during the first visit to facilitate a clear understanding of tendon protection . At 6 weeks post immobilization, the tendon is “tested” with full extension place and hold. If the patient is unable to maintain DIP joint extension, the orthosis is continued for another week. If healing is sufficient to maintain full extension, gentle active flexion exercises are initiated. Best practice is to move forward gradually with gentle active range of motion. If attenuation occurs, it is very difficult to remedy, and most patients are left with some degree of extensor lag . If extensor lag is in excess of 30°, there is noted impact on function . There is a delicate balance between progressing flexion while maintaining extension versus progressing beyond tissue tolerance thus increasing extension lag. Thorough documentation including analysis of goniometric measurements at every therapy session is required . The savvy patient is able to progress orthosis weaning between therapy sessions based on observation of his or her ability to maintain DIP joint extension. With most patients, however, advance weaning only after careful observation and measurement in the clinic. If, after 2–3 days of active flexion during exercise sessions, DIP joint extension is maintained, the patient is instructed to advance orthosis weaning. Continue to progressively increase time-out of the orthosis as the patient is able to maintain joint extension. Typically, full transition to nighttime-only orthosis use occurs within 2–3 weeks of initiation of weaning. The patient may need to continue with nighttime splinting for 2–4 weeks after daytime orthosis use has been discontinued. Protection during contact sports is recommended through week 12. Typically, patients who sustain mallet finger injuries do not require formalized strengthening, desensitization, or work conditioning activities and rarely even require passive range of motion in order to gain functional flexion without a significant lag .

Mallet thumb injuries are much less common than mallet finger injuries and are typically open [29]. These injuries are managed in the same fashion as mallet finger injuries .

Extensor Pollicis Longus Zone I Repair

Extensor pollicis longus (EPL) injuries usually occur as the result of a laceration over the dorsum of the thumb; however, associated crush injuries are not uncommon and result in an inability to fully extend the IP joint. The literature lacks in studies of EPL repair with the vast majority being conducted on the extensor system of the fingers [5]. Typically, zone I EPL injuries are managed in the same fashion as mallet finger injuries, with continuous extension immobilization of the interphalangeal (IP) joint in slight hyperextension for 6 weeks. [11]. Refer to the section “Mallet Finger Injuries” for treatment recommendations and considerations. Zone I EPL repairs often require a focus on scar management and efforts to increase IP flexion once the tendon is sufficiently healed. Generally, active range of motion is begun 4 weeks post repair followed by passive range of motion and discharge of orthosis 6 weeks post repair. Static progressive or dynamic orthosis use may be necessary in order to gain full IP flexion. Strengthening is initiated at 8 weeks post repair. As with mallet finger , careful monitoring for extension lag and appropriate adjustment of the therapeutic program is required .

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree