INTRODUCTION

Rheumatologic diseases are commonly encountered in rehabilitation practice, in both inpatient and outpatient (ambulatory) settings. These diseases are diffuse and multifactorial. Most are poorly understood. In some diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia, patients present with vague initial symptoms of fatigue and morning stiffness that can progress to a chronic debilitating process. In others, such as giant cell arteritis, immediate diagnosis and treatment is required to prevent disastrous consequences. Most rheumatologic diseases have limited treatment options, some of which (eg, glucocorticosteroids) have significant side effects.

The role of the physiatrist is to recognize common rheumatologic diseases, treat pain conditions that are common in patients with rheumatologic diseases, and assist in diagnosis and referral for proper treatment. A priority is to maintain function in patients by means of proper bracing and assistive devices, physical activities, and exercise programs. Because many rheumatologic diseases are chronic and debilitating, a team approach is preferred. The physiatrist should lead a team of professionals—including rheumatologists; psychiatrists; physical, occupational, and speech therapists; counselors; and social workers—whose combined efforts aid in diagnosing the disease, controlling pain, and improving function.

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Symmetric polyarticular inflammatory arthritis.

Diagnostic criteria include morning stiffness of joints, lasting at least 1 hour; involvement of three or more joints; and, in the hand joint, involvement of at least one metacarpophalangeal (MCP) or proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint.

Additional features include the presence of rheumatoid nodules, positive serum rheumatoid factor (seen in 85% of patients), and bony erosions on radiographs.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most common inflammatory arthritis, affecting more than 1.5 million adults in the United States. It has a slow, insidious onset and is a chronic, progressive, systemic rheumatic disease. RA affects more women than men, and more whites than other races, with the peak incidence in the third to sixth decades of life. It is thought to be caused by a combination of genetic, environmental, and immune-mediated factors. The most consistent genetic association is with class II major histocompatability genes, especially those containing a specific five amino acid sequence in the hypervariable region of HLA-DR4. Other genetic polymorphisms also are found. RA is associated with several bacterial and viral infections; these include Mycoplasma, Mycobacterium, enteric bacteria, parvovirus, retroviruses, and Epstein-Barr virus.

Clinical criteria for diagnosis of RA are based on the classification criteria published in 1987 by the American Rheumatism Association, now the American College of Rheumatology (ACR; Table 22–1). The criteria were updated in 2010 to focus on features seen in earlier stages of the disease that are consistent with more erosive disease (Table 22–2). In using the updated criteria, each feature that is present is scored as 1 point, and a total score equal to or greater than 6 is indicative of RA.

| Clinical Criteria | Diagnostic Criteria (Higher Specificity) |

|---|---|

| At least 6 months of: At least 1 hour of morning stiffness of affected joints Simultaneous involvement of at least 3 joints with observable soft tissue swelling of fluid Involvement of at least 1 joint in wrist/hand (MCP, PIP) Simultaneous bilateral involvement of same joint | Presence of rheumatoid nodules Positive serum rheumatoid factor Radiographic changes, including bony erosions at affected joints |

| Points | Swollen or Tender Joints | Laboratory Studies | Acute Phase Reactants | Duration of Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Negative RF + CCP IgG (ACPA) | Normal CRP and ESR | Less than 6 weeks | |

| 1 | 1 large joint (shoulder, elbow, hip, knee, ankle) | Abnormal CRP or ESR | More than 6 weeks | |

| 2 | 2–10 large joints | Low positive RF or CCP IgG (ACPA) | ||

| 3 | 1–3 small joints (not including DIP, first MTP, or first CMC, as these are commonly involved in OA) | Highly positive RF or CCP IgG (ACPA) | ||

| 4 | 4–10 small joints | |||

| 5 | > 10 joints |

Onset is usually polyarticular and generally symmetric in the joints involved. The metacarpophalangeal (MCP), metatarsophalangeal (MTP), wrist, and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints are most frequently affected. Other joints that may be involved are the knee, hip, ankle, shoulder, and cervical spine. In addition to patients’ subjective reports of joint pain, inflammatory arthritides such as RA produce signs that include more than 1 hour of morning stiffness in affected joints, and tenderness and warmth to joint palpation. Joint effusions are also common.

A wide spectrum of severity is seen, reflecting variation in joint destruction and extraarticular organ involvement. Systemic manifestations can include rheumatoid nodules, cardiovascular or pulmonary disease, vasculitis, serositis, and eye disease. Felty’s syndrome is an uncommon but severe subset of RA characterized by neutropenia and splenomegaly.

Despite the disease name, a positive serum rheumatoid factor (RF) test does not always indicate that a patient has RA. RF, an autoantibody that binds to the Fc portion of immunoglobulin G (IgG), is also present in other rheumatic diseases, including scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, and Sjögren’s syndrome. Absence of serum RF is also seen in a small percentage of patients with RA.

Serum testing for cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) IgG or α-citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) is more specific than, and equally as sensitive as, the serum RF test. CCP and ACPA are often positive years before a clinical diagnosis is made. They are also used as a marker for erosive disease.

Other pertinent laboratory findings seen with inflammatory arthritic processes include elevated peripheral white blood cell count with a “left shift” (elevated leukocytes in the differential) and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Anemia of chronic disease and increase in platelets are also seen in patients with RA.

Synovial fluid analysis reveals moderate inflammatory (or group II) changes as well as decreased levels of complement C4 and C2, normal glucose, no evidence of crystals, and negative cultures and Gram stain (Table 22–3).

| Parameter | Characteristic Findings |

|---|---|

| Color | Yellow or straw |

| Opacity | Transparent to slightly cloudy |

| Viscosity | Variably decreased |

| Mucin clot test | Fair to poor |

| White blood cell (WBC) count | 3000–50,000/mm3 |

| WBC differential | >70% polymorphonuclear leukocytes |

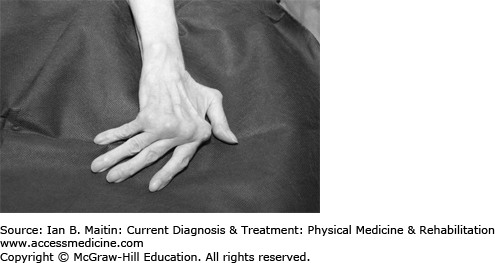

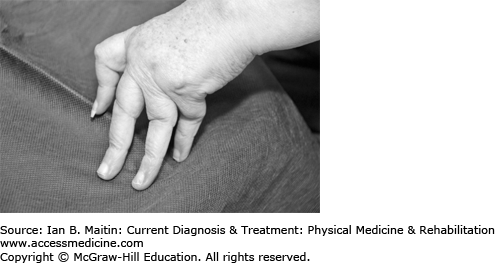

Radiographs are used for diagnosis and monitoring of disease course in RA. The hallmarks of RA are juxtaarticular soft tissue swelling, osteopenia and osteoporosis, marginal bony erosions and cysts, diffuse joint space narrowing, and, at later stages, joint ankylosis. Subluxations occur, including swan-neck and boutonnière deformities in the fingers and ulnar deviation at the wrist (Figures 22–1 and 22–2). Later changes in RA are irreversible.

The chronic inflammatory processes affect the transverse and alar ligaments on the upper cervical vertebrae (C1–C2) and in combination with erosion of the odontoid process can lead to potentially significant instability at this joint.

Findings on tissue biopsy include synovial lining hyperplasia, lymphocytic infiltration, and neoangiogenesis. There is destruction of periarticular bone and cartilage at joint margins. The synovial membrane extends, forming a pannus. The activation of multiple inflammatory mediators, including cytokines, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin-1β, allows potential opportunities for targeted treatment. This same immune-mediated process also produces damage to tissues in other organs.

Hand and wrist deformities are seen in patients as the disease progresses. Early research showed that weakening of the extensor carpi ulnaris muscle by the erosive tenosynovitis leads to radial deviation of the wrist with compensatory ulnar deviation of the fingers (Figure 22–1), forming a zig-zag pattern. To prevent this deformity and maintain the functional use of the hand, a dynamic MCP extension assist splint can be used.

With ongoing inflammation at the wrist, the ulnar collateral ligament is destroyed. This allows the ulnar head to move up as a dorsal prominence. With this “piano key” styloid deformity, the ulna is easily depressed by the examiner’s fingers. Prefabricated wrist working splints are highly effective in reducing wrist pain after 4 weeks of splint wearing in RA patients with wrist arthritis.

Common deformities associated with RA in the hand include the swan-neck and boutonnière deformities (Figure 22–2). In swan-neck deformity shortening of the intrinsic muscles exerts tension on the dorsal tendon sheath, leading to hyperextension of the PIP joint. The distal interphalangeal (DIP) and MCP joints are in flexion.

Chronic inflammation of the PIP joint may cause the extensor hood to stretch or avulse. The PIP joint moves into excessive flexion, producing a boutonnière deformity. The DIP joint remains in hyperextension based on the pull of the extensor tendons. For patients with RA and a mobile deformity, silver ring splints and prefabricated thermoplastic splints are equally effective and acceptable. (These splints are further described in Chapter 28; see also Figures 28–1 and 28–2.)

Resting wrist and hand splints should not be used as a routine treatment of patients with early RA as there is no significant difference made for grip strength, joint deformity, hand function, and pain.

The atlantoaxial joint is prone to subluxation in RA. Symptoms of cervical subluxation are pain radiating up into the occiput, painless sensory loss in the hands, paresthesias in the shoulders and arms with movement of the head, or slowly progressive spastic quadriparesis. Lateral cervical spine radiographs views should be examined for more than 3 mm of separation between the odontoid peg and the axial arch. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also helpful for evaluation of these joints.

Neurologic symptoms are not necessarily related to the degree of subluxation seen on radiographs and may be more correlated to variations in the diameter of the spinal canal. Findings of neurologic loss should be treated as urgent and require further evaluation by a surgeon.

Although improvements in therapy have decreased the incidence of severe extraarticular complications associated with RA, it is important to be aware of them. One of the most common extraarticular findings is rheumatoid nodules. Rheumatoid nodules are usually noted as subcutaneous masses attached to the periosteum. They occur in 15–20% of patients with RA, most often on extensor surfaces or pressure points, such as the olecranon process and the proximal ulna, as well as on tendons. However, rheumatoid nodules have also been found in heart, lung, sclera, and the central nervous system of patients with RA. Activation of complement in the terminal arterioles causes increases in local histiocytes and fibroblasts as well as an influx of macrophages. These focal areas of granulation tissue grow and expand, leaving behind central necrosis due to destruction of the connective tissue matrix to become the palpable rheumatoid nodules.

Management of RA encompasses a range of strategies centered on halting disease progression, maximizing functional ability, and supporting the patient’s overall health. Pharmacotherapy, therapeutic exercise, and use of adaptive devices are mainstays of treatment. Heating and cooling modalities may relieve pain associated with disease flares and inflammation. The relationship between dietary or lifestyle factors and exacerbations of disease in rheumatoid arthritis and other diseases having autoimmune features awaits clarification. Readers are referred elsewhere for discussion of complementary strategies, which include fish oil supplementation, dietary changes (eg, gluten-free, lactose-free, vegan, or vegetarian diets), and stress-reduction activities (eg, meditation, yoga).

Medications used in the management of RA include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), low-dose systemic corticosteroids, and biologic and nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). Selection of medication is based on three factors: (1) duration of disease, (2) standardized measures of disease activity, and (3) signs of poor prognosis. Indicators of poor prognosis include greater clinical disease activity, evidence of bony erosions on radiographs, higher levels of serum RF, higher levels of anti-CCP antibodies, higher ESR, and higher C-reactive protein (CRP) level.

Current treatment protocols emphasize the need for early and aggressive treatment to halt disease progression and achieve remission. The development of biologic and nonbiologic DMARDs has provided a key strategy in this effort. Tables 22–4 and 22–5 summarize information about agents in each group. For patients with longer disease duration, higher disease activity, or signs of poor prognosis, dual or triple combinations of nonbiologic DMARDs are used. Biologic DMARDs can improve disease activity, function, and quality of life in addition to reducing radiographic progression of the disease. These medications can be used alone or in combination with methotrexate. Because no additive effect has been reported and risk of toxicity is higher when biologic DMARDs are used in combination, multidrug treatment with these agents is not recommended.

| Medication | Duration of Disease | Disease Activity | Indicators of Poor Prognosis Presenta |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methotrexate | < 6 mo | Moderate–high | Yes |

| Leflunomide | > 24 mo | Moderate | Yes |

| Hydroxychloroquine | < 24 mo | Low | No |

| Minocycline | < 6 mo | Low | No |

| Sulfasalazine | >24 mo | Moderate | No |

| Medication | Duration of Disease | Disease Activity | Prior Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

Anti-tumor necrosis factor: Etanercept Infliximab Adalimumab | < 6 month duration of disease Or,> 6 months within adequate response to methotrexate (MTX) | High | No prior use of DMARDs Or, inadequate response to MTX |

Abatacept Rituximab | Indicators of poor prognosisa | Moderate–high | Inadequate response to MTX and other DMARDs |

Nonpharmacologic treatments, including physical and occupational therapy, have a complementary role to drug therapy in managing inflammatory arthritis. Therapeutic exercise can maintain or improve joint range of motion, aerobic capacity, and muscle strength. Clinicians face three major challenges concerning the use of these treatments: limited research evidence, lack of knowledge of providers of available treatments, and variability in delivery of multidisciplinary health care around the world.

Despite strong evidence suggesting that exercise is effective in improving disease-related characteristics and functional ability in RA patients, only 26% of patients with RA received a referral from rheumatologists for rehabilitation. However, the clinical and laboratory safety profiles for patients with RA participating in therapeutic exercise programs are good. No deleterious effects were found in any of the published studies.

Aerobic capacity training combined with muscle strength training is recommended for patients with RA. Both water-based and land-based aerobic capacity training show a positive effect on aerobic capacity and muscle strength. Caution must be used in prescribing high-intensity weight-bearing exercises for patients who have preexisting significant radiologic damage of large joints, as some patients may develop additional damage. During an acute flare, joint protection, including orthoses, and relative rest of affected joints are indicated. Isometric muscle exercises can be used until the flare has resolved.

Tai chi has been found to have statistically significant benefits on lower extremity range of motion, in particular ankle range of motion, for people with RA and has not been found to exacerbate symptoms of RA.

Although there is evidence that foot orthoses reduce pain and improve functional ability, there is no consensus as to the recommended type. Foot orthoses range from simple cushioned insoles to custom-made rigid cast devices. There is evidence that extra-depth shoes and molded insoles decreases pain on weight-bearing activities such as standing, walking, and stair-climbing.

Patients with RA may use adaptive devices to help with activities of daily living or mobility. There is currently very limited evidence for the effect of assistive technology for adults with RA.

Comprehensive occupational therapy is effective in improving function in people with moderate to severe arthritis. Specific interventions, including joint protection and hand exercises, have been found to be effective in patients with RA. High-quality evidence was found for beneficial effects of joint protection and patient education. There is also strong evidence for the efficacy of appropriate splinting to decrease joint pain.

Work disability is common in RA and accounts for a large fraction of the costs associated with the disease. Patients with RA are at risk of work disability from the very start of their symptoms. Twenty to 30% of patients with RA become permanently work disabled during the first 2–3 years of the disease. Risk factors for early work disability include a physically demanding job, older age, and lower educational level, as well as the level of functional disability in daily activities. People with RA who are work disabled have more joint involvement, radiographic damage, and laboratory abnormalities than people who are working. Work disability results from complex interactions of a medical disease, demographic variables, social conditions, and government policies. Although there is general agreement that vocational assessment and intervention should occur early in the course of RA, evidence for vocational rehabilitation is sadly lacking.

OSTEOARTHRITIS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Most common joint disorder in the United States.

“Wear-and-tear” degenerative disease that preferentially affects weight-bearing joints.

Patients report dull, achy pain with stiffness; morning stiffness lasts less than 30 minutes.

Radiographic imaging is the gold standard for diagnosis.

Osteoarthritis is the most common joint disorder in the United States, affecting approximately 27 million people. Although the precise cause of the disorder varies from case to case, osteoarthritis is generally considered to be a “wear-and-tear” type of degenerative disease. Regardless of etiology, the underlying mechanism of degeneration is thought to be a biomechanical or biochemical breakdown of the arthrodial cartilage in synovial joints. Joints that are weight bearing are preferentially affected; namely, the knees, hips, cervical and lumbar spine, as well as joints of the hands and feet, which are prone to overuse.Table 22–6 provides a more complete list of risk factors for developing osteoarthritis.

In most patients, the major morbidity and presenting complaint is pain, usually described as dull and achy. This may be associated with stiffness, particularly morning stiffness lasting less than 30 minutes. In more advanced disease states, osteoarthritis is also associated with joint crepitus and loss of both active and passive range of motion.

Diagnosis may be made on the basis of clinical findings, although radiographic imaging is the gold standard for confirmation. Certain radiographic features are considered tantamount to diagnosis. These include bony hypertrophy, joint-space narrowing, subchondral cysts, bony sclerosis, and bone spur formation. Nonetheless, one of the main caveats of clinical presentation, as shown by recent studies, is that severity of disease in imaging is discordant to the amount of pain reported by patients. Therefore, appearance on imaging should not be used as a guide for symptomatic management.

In most patients osteoarthritis occurs as a primary disorder resulting from degeneration over time. However, in certain cases, antecedent trauma or underlying disease may precipitate a secondary osteoarthritis. The main condition to consider and rule out in the differential diagnosis is RA (Table 22–7).

Treatment of osteoarthritis is largely empiric and is targeted at symptom management. Over-the-counter pain medications and lifestyle modification are typically sufficient for the majority of patients. Weight loss, if patients are overweight, is encouraged to reduce stress on painful joints. For osteoarthritis that requires further intervention, the ACR’s 2012 guidelines encourage practitioners to utilize both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic modalities. Specific recommendations are tailored to the joint involved, based on current evidence (Tables 22–8, 22–9, and 22–10). Orthotic use in patients with compression fractures of the spine due to osteoarthritis is further described in Chapter 28.

| Pharmacologic Therapy | Nonpharmacologic Therapy |

|---|---|

| Conditionally recommended: Topical capsaicin Topical NSAIDs, including trolamine salicylatea Oral NSAIDs, including COX-2 inhibitors Tramadol Conditionally not recommended:Opioid analgesics Intraarticular therapies | Conditionally recommended: Assessment of ADLs (either by physician or by occupational therapist) Adaptive equipment as needed (ie, builtup eating utensils, easy-open containers, etc) Instruction in joint protection Thumb spica splinting in basal joint OA Instruction in self-use of thermal modalities |

| Pharmacologic Therapy | Nonpharmacologic Therapy |

|---|---|

| Conditionally recommended: Acetaminophen Oral NSAIDs, including COX-2 inhibitors Topical NSAIDs Tramadol Intraarticular corticosteroids Conditionally not recommended:Chondroitin sulfate Glucosamine Topical capsaicin No recommendations (positive or negative):Intraarticular hyaluronic acid Duloxetine Opioid analgesics | Strongly recommended: Aerobic or resistance-based land exercise Aquatic therapy Weight loss (if overweight) Conditionally recommended:Self-management programs Manual therapy in combination with supervised exercise Psychosocial interventions Medially directed patellar taping Medially wedged insoles for lateral compartment OA Laterally wedged subtalar strapped insoles for medial compartment OA Instruction in self-use of thermal modalities Use of walking aids, if needed Tai chi Acupuncturea Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|