9 Reflex therapies

Technique: connective tissue manipulation/bindegewebsmassage

Features

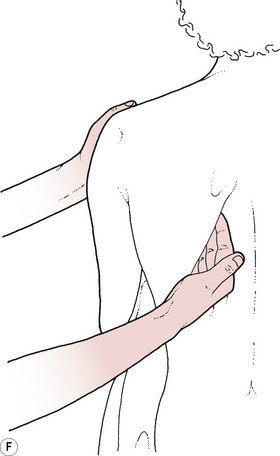

Connective tissue manipulation (CTM) is a soft tissue manipulative therapy which is, conceptually, a reflex therapy. It influences cutaneovisceral autonomic reflexes (see Chapter 3) to induce balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. It utilises connective tissue (CT) zones derived from the skin zones of Head and the muscle zones of McKenzie. These are found principally on the back where they can be seen and palpated. The zones are both visible and palpable, with a degree of inter-rater reliability (Holey & Watson 1995) Acute zones are seen as ‘puffy’ raised areas which feel soft to the touch, with underlying tension felt when superficial layers are moved on deeper layers. Chronic zones are recognised as drawn-in areas in which the tissues are palpated as tight and adherent (Haase 1962). They are often hypersensitive. The zones (see Fig. 3.7) are assessed to detect the level of autonomic balance and specific functional problems. For example, a positive liver zone may indicate recent drug therapy, heavy social drinking or disease. The number of visible and palpable zones indicates the generality of autonomic imbalance. The zones can indicate the degree to which imbalance has occurred or can inform progression of treatment or location of strokes to be applied, or can indicate cautions. A specific stretch manipulation is applied to the fascial layer and is thought to stimulate segmental and suprasegmental cutaneovisceral reflexes. All structures sharing the same spinal segmental innervation are stimulated via the autonomic nervous system (ANS), resulting in effects that include vasodilatation and alterations in smooth muscle tone. The suprasegmental effects are mediated in the medulla and wider physiological effects are achieved, such as improved balance between the two components of the ANS, endocrine and hormonal balancing and raised beta-endorphin levels. It produces a feeling of well being and increased flexibility.

Patients who may benefit from this treatment are those with:

• Local mechanical musculoskeletal problems, for example scarring or shin splints;

• Hormonal problems, for example women experiencing menopausal or menstrual symptoms;

• Visceral problems, for example bowel disorders; and

• Autonomic problems, for example complex regional pain syndrome, intractable nerve root pain.

Categories—Preparatory Strokes: Fascial Technique; Skin Technique; Subcutaneous Technique; Flat Technique

Manipulation: fascial (fazien) technique

Purpose

To reduce trophoedematous changes in zonal areas.

To promote fluid level balance.

To achieve balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems.

To reduce sympathetically maintained pain.

To produce a feeling of well being.

To increase local and general flexibility.

To enhance hormonal and endocrine function.

Procedure

This is CTM ‘proper’, which produces the strong autonomic reflex reactions.

The pad of the therapist’s third finger makes contact with the skin (Fig. 9.1A).

The finger is reinforced by the ring finger.

The distal interphalangeal joint is flexed, to gather up the slack superficially in the tissues.

The therapist should then push into the end-feel using the hand and arm to exert a traction effect at the fascial layer.

Each stroke must be performed in the palmar or radial direction of the operating hand.

The stroke must be accurately aimed at the correct tissue interface.

The tissues must be adequately prepared by preparatory techniques to produce the desired effect.

Each stroke must produce a cutting sensation and a triple response, or adverse reactions will occur.

All strokes must be within the patient’s tolerance of discomfort.

The strokes must begin at the sacrum.

Progression of the strokes depends on the individual patient’s response and on the aims of treatment: they can be dictated by the zones, segmental relationships and understanding of the underlying pathological processes.

Manipulation: flat (flashige) technique

Procedure

The patient should be side-lying.

The therapist sits behind the patient.

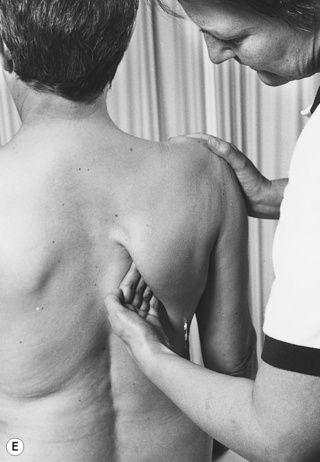

The therapist’s thumbs are flexed, the nails placed together and the tips hooked under the subcutaneous tissues at their insertion into the sacral border (Figs. 9.1E, F).

The therapist’s fingers are spread over the skin, which they pull gently towards the thumbs.

The thumbs are pushed away, towards the fingers, applying a stretch to the fascia, to the end-feel of the movement.

Do not stretch into the end-feel by exerting an over-pressure, to produce a ‘cutting’ reaction.

Proceed the strokes in the following order: along the sacral border, along erector spinae (both edges), along the vertebral border of the scapula and along the greater trochanter.

Manipulation: subcutaneous (unterhaut) technique

Procedure

The therapist stands to one side of the patient’s trunk.

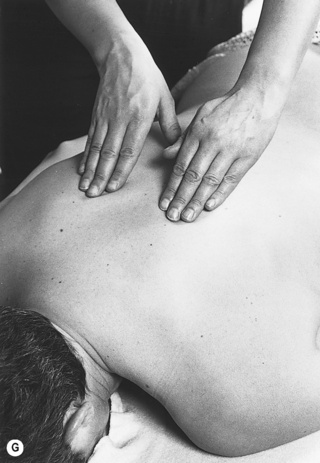

The therapist places the pads of the fingers of both hands lightly on the skin (Figs. 9.1G, H).

The finger pads sink into the subcutaneous layer.

Small pushing movements are made in a cephalad direction.

The skin is moved with the fingers and the stimulus must remain in this layer.

The strokes can be progressed over the area requiring treatment or over an area implicated in a desired reflex effect.

Technique: myofascial release

Features

A stretching technique that recognises and utilises the craniosacral rhythm.

The craniosacral rhythm, believed to be a pulsing of the cerebrospinal fluid, is particularly involved with release of the cranial base, the dural tube and the pelvic and respiratory diaphragms.

Tightening of the myofascia is identified by palpation.

Passive stretching along the direction of the muscle fibres is followed by a hold, until release is felt and the process is repeated until there is no further release.

Somato-emotional release can occur, so it is important that the therapist is qualified to work with and support this release, or functions within a multidisciplinary team.

Procedure

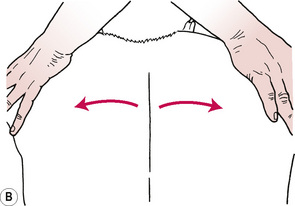

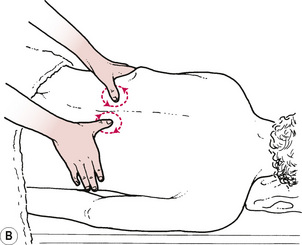

A longitudinal stretch is applied along the direction of the muscle fibres by:

1. Applying the therapist’s fingertips on the skin and moving the fingers and underlying skin apart;

2. Placing crossed hands on the skin, exerting pressure through the ulnar border of the hands and separating the hands to stretch the underlying skin (Figs. 9.2A, B);

3. Firmly grasping the limb and pulling along its long axis, the muscle to be stretched dictating the position of the joints (e.g. internal rotation with adduction); and

4. Increasing the localisation of a longitudinal stretch by placing one hand on the proximal border of the muscle under stretch (Figs. 9.2C, D).

Technique: segmentmassage

Features

Effective as a reflex technique.

Works by stimulating the ANS via the skin by a mechanism similar to that of CTM.

It is particularly effective at the maximal tenderness points of CT zones.

It has a more gentle, gradual effect than CTM, working predominantly in the subcutaneous layer but also the fascial layer and the periosteum.

It produces a strong parasympathetic effect and is less likely to produce an adverse reaction.

A wide variety of techniques are included, some of which relate to spinal segments and others to the dermatomes in the limbs.

Assessment of the patient involves stroking segmentally with the thumb tips; a ‘paradoxical reaction’ which leaves white lines rather than the triple response of CTM is produced.

If the skin does not move or react appropriately, vibrations are performed.

Segmentmassage manipulations

Procedure 1

The patient sits on a stool, pelvis tilted forwards to sit on the ischial tuberosities.

The therapist sits behind and places her hands around the patient’s iliac crests.

The therapist’s thumb tips are placed on the skin on the border of erector spinae and pushed into the muscle layer.

The thumbs are circled away from the spine (Figs. 9.3A, B).

The hands gradually progress in a cranial direction, circling in each spinal segment.

Procedure 2

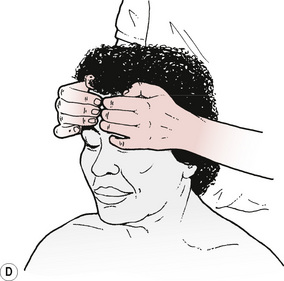

The patient sits on a chair and leans back on to the therapist, who is standing behind.

The patient’s head is supported on the therapist.

The therapist places the tips of her fingers on the patient’s forehead, with the fingernails of each hand back-to-back (Figs. 9.4C, D).

Small light circles are followed with the fingertips.

The skin should move with the fingers; there should be no glide over the skin.

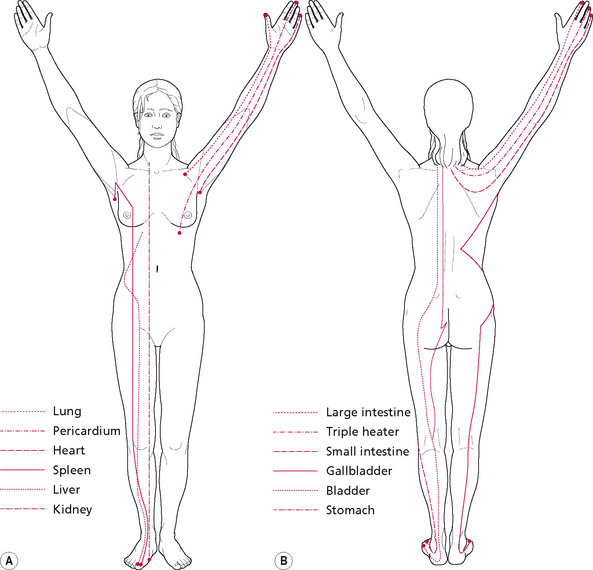

Procedure 3

The patient is sitting upright.

The therapist stands behind and grasps the point of the patient’s shoulder.

The other hand slides underneath the scapula, with fingers on teres minor and the thumb under the scapula.

The length of the rhomboid attachment is thumb kneaded (on the periosteum) on the vertebral border of the scapula.

The technique is then modified so that the hand is turned round and small circular movements are applied to the undersurface of the scapula (Figs. 9.4E, F).

Technique: periostealmassage

Procedure

The therapist flexes all the joints of her index finger.

Contact is made between the ulnar border of the proximal interphalangeal joint of the index finger and the point to be treated.

Pressure is increased through this point until the periosteum is reached.

Tiny circular movements are performed with the hand, maintaining the pressure to ensure that the knuckle does not glide over the skin (2 minutes).